Newton's cradle

Newton's cradle is a device, usually made of metal, that demonstrates the principles of conservation of momentum and conservation of energy in physics with swinging spheres. When one sphere at the end is lifted and released, it strikes the stationary spheres, compressing them and thereby transmitting a pressure wave through the stationary spheres, which creates a force that pushes the last sphere upward. The last sphere swings back and strikes the stationary spheres, repeating the effect in the opposite direction. The device is named after 17th-century English scientist Sir Isaac Newton and was designed by French scientist Edme Mariotte. It is also known as Newton's pendulum, Newton's balls, Newton's rocker or executive ball clicker (since the device makes a click each time the balls collide, which they do repeatedly in a steady rhythm).[1][2]

Operation

[edit]When one of the balls at the end ("the first") is pulled sideways, the attached string constrains it along an upward arc. When released it strikes the second ball and comes nearly, but not entirely, to a dead stop. The succeeding ball acquires most of the velocity of the first ball propagates the diminished momentum. Eventually the last ball, having received a successively diminished portion of the first's energy and momentum, begins the process anew in the opposite direction. Each impact produces a sonic wave that propagates through the medium of the intermediate balls. (Any efficiently elastic material such as steel suffices, as long as the kinetic energy is temporarily stored as potential energy in the compression of the material rather than being lost as heat. This is similar to bouncing one coin of a line of touching coins by striking it with another coin, and which happens even if the first struck coin is constrained by pressing on its center such that it cannot move.)[citation needed] In each phase of the process, efficient mechanical energy is lost; Newton's cradle is not a perpetual motion machine. This would stand true even in the absence of air resistance, as in a vacuum.

There are slight movements in all the balls after the initial strike, but the last ball receives most of the initial energy from the impact of the first ball. When two (or three) balls are dropped, the two (or three) balls on the opposite side swing out. Some say that this behavior demonstrates the conservation of momentum and kinetic energy in elastic collisions. However, if the colliding balls behave as described above with the same mass possessing the same velocity before and after the collisions, then any function of mass and velocity is conserved in such an event.[3] Thus, this first-level explanation is a true, but incomplete, description of the motion.

Physics explanation

[edit]

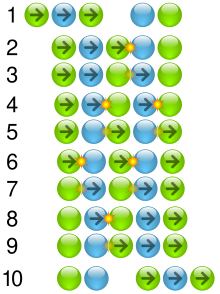

Newton's cradle can be modeled fairly accurately with simple mathematical equations with the assumption that the balls always collide in pairs. If one ball strikes four stationary balls that are already touching, these simple equations can not explain the resulting movements in all five balls, which are not due to friction losses. For example, in a real Newton's cradle the fourth has some movement and the first ball has a slight reverse movement. All the animations in this article show idealized action (simple solution) that only occurs if the balls are not touching initially and only collide in pairs.

Simple solution

[edit]The conservation of momentum (mass × velocity) and kinetic energy (1/2 × mass × velocity2) can be used to find the resulting velocities for two colliding perfectly elastic objects. These two equations are used to determine the resulting velocities of the two objects. For the case of two balls constrained to a straight path by the strings in the cradle, the velocities are a single number instead of a 3D vector for 3D space, so the math requires only two equations to solve for two unknowns. When the two objects have the same mass, the solution is simple: the moving object stops relative to the stationary one and the stationary one picks up all the other's initial velocity. This assumes perfectly elastic objects, so there is no need to account for heat and sound energy losses.

Steel does not compress much, but its elasticity is very efficient, so it does not cause much waste heat. The simple effect from two same-mass efficiently elastic colliding objects constrained to a straight path is the basis of the effect seen in the cradle and gives an approximate solution to all its activities.

For a sequence of same-mass elastic objects constrained to a straight path, the effect continues to each successive object. For example, when two balls are dropped to strike three stationary balls in a cradle, there is an unnoticed but crucial small distance between the two dropped balls, and the action is as follows: the first moving ball that strikes the first stationary ball (the second ball striking the third ball) transfers all of its momentum to the third ball and stops. The third ball then transfers the momentum to the fourth ball and stops, and then the fourth to the fifth ball.

Right behind this sequence, the second moving ball is transferring its momentum to the first moving ball that just stopped, and the sequence repeats immediately and imperceptibly behind the first sequence, ejecting the fourth ball right behind the fifth ball with the same small separation that was between the two initial striking balls. If they are simply touching when they strike the third ball, precision requires the more complete solution below.

Other examples of this effect

[edit]The effect of the last ball ejecting with a velocity nearly equal to the first ball can be seen in sliding a coin on a table into a line of identical coins, as long as the striking coin and its twin targets are in a straight line. The effect can similarly be seen in billiard balls. The effect can also be seen when a sharp and strong pressure wave strikes a dense homogeneous material immersed in a less-dense medium. If the identical atoms, molecules, or larger-scale sub-volumes of the dense homogeneous material are at least partially elastically connected to each other by electrostatic forces, they can act as a sequence of colliding identical elastic balls.

The surrounding atoms, molecules, or sub-volumes experiencing the pressure wave act to constrain each other similarly to how the string constrains the cradle's balls to a straight line. As a medical example, lithotripsy shock waves can be sent through the skin and tissue without harm to burst kidney stones. The side of the stones opposite to the incoming pressure wave bursts, not the side receiving the initial strike. In the Indian game carrom, a striker stops after hitting a stationery playing piece, transferring all of its momentum into the piece that was hit.

When the simple solution applies

[edit]For the simple solution to precisely predict the action, no pair in the midst of colliding may touch the third ball, because the presence of the third ball effectively makes the struck ball appear more massive. Applying the two conservation equations to solve the final velocities of three or more balls in a single collision results in many possible solutions, so these two principles are not enough to determine resulting action.

Even when there is a small initial separation, a third ball may become involved in the collision if the initial separation is not large enough. When this occurs, the complete solution method described below must be used.

Small steel balls work well because they remain efficiently elastic with little heat loss under strong strikes and do not compress much (up to about 30 μm in a small Newton's cradle). The small, stiff compressions mean they occur rapidly, less than 200 microseconds, so steel balls are more likely to complete a collision before touching a nearby third ball. Softer elastic balls require a larger separation to maximize the effect from pair-wise collisions.

More complete solution

[edit]A cradle that best follows the simple solution needs to have an initial separation between the balls that measures at least twice the amount that any one ball compresses, but most do not. This section describes the action when the initial separation is not enough and in subsequent collisions that involve more than two balls even when there is an initial separation. This solution simplifies to the simple solution when only two balls touch during a collision. It applies to all perfectly elastic identical balls that have no energy losses due to friction and can be approximated by materials such as steel, glass, plastic, and rubber.

For two balls colliding, only the two equations for conservation of momentum and energy are needed to solve the two unknown resulting velocities. For three or more simultaneously colliding elastic balls, the relative compressibilities of the colliding surfaces are the additional variables that determine the outcome. For example, five balls have four colliding points and scaling (dividing) three of them by the fourth gives the three extra variables needed to solve for all five post-collision velocities.

Newtonian, Lagrangian, Hamiltonian, and stationary action are the different ways of mathematically expressing classical mechanics. They describe the same physics but must be solved by different methods. All enforce the conservation of energy and momentum. Newton's law has been used in research papers. It is applied to each ball and the sum of forces is made equal to zero. So there are five equations, one for each ball—and five unknowns, one for each velocity. If the balls are identical, the absolute compressibility of the surfaces becomes irrelevant, because it can be divided out of both sides of all five equations, producing zero.

Determining the velocities[4][5][6] for the case of one ball striking four initially touching balls is found by modeling the balls as weights with non-traditional springs on their colliding surfaces. Most materials, like steel, that are efficiently elastic approximately follow Hooke's force law for springs, , but because the area of contact for a sphere increases as the force increases, colliding elastic balls follow Hertz's adjustment to Hooke's law, . This and Newton's law for motion () are applied to each ball, giving five simple but interdependent differential equations that can be solved numerically.

When the fifth ball begins accelerating, it is receiving momentum and energy from the third and fourth balls through the spring action of their compressed surfaces. For identical elastic balls of any type with initially touching balls, the action is the same for the first strike, except the time to complete a collision increases in softer materials. Forty to fifty percent of the kinetic energy of the initial ball from a single-ball strike is stored in the ball surfaces as potential energy for most of the collision process. Of the initial velocity, 13% is imparted to the fourth ball (which can be seen as a 3.3-degree movement if the fifth ball moves out 25 degrees) and there is a slight reverse velocity in the first three balls, the first ball having the largest at −7% of the initial velocity. This separates the balls, but they come back together just before as the fifth ball returns. This is due to the pendulum phenomenon of different small angle disturbances having approximately the same time to return to the center.

The Hertzian differential equations predict that if two balls strike three, the fifth and fourth balls will leave with velocities of 1.14 and 0.80 times the initial velocity.[7] This is 2.03 times more kinetic energy in the fifth ball than the fourth ball, which means the fifth ball would swing twice as high in the vertical direction as the fourth ball. But in a real Newton's cradle, the fourth ball swings out as far as the fifth ball. To explain the difference between theory and experiment, the two striking balls must have at least ≈ 10 μm separation (given steel, 100 g, and 1 m/s). This shows that in the common case of steel balls, unnoticed separations can be important and must be included in the Hertzian differential equations, or the simple solution gives a more accurate result.

Effect of pressure waves

[edit]The forces in the Hertzian solution above were assumed to propagate in the balls immediately, which is not the case. Sudden changes in the force between the atoms of material build up to form a pressure wave. Pressure waves (sound) in steel travel about 5 cm in 10 microseconds, which is about 10 times faster than the time between the first ball striking and the last ball being ejected. The pressure waves reflect back and forth through all five balls about ten times, although dispersing to less of a wavefront with more reflections. This is fast enough for the Hertzian solution to not require a substantial modification to adjust for the delay in force propagation through the balls. In less-rigid but still very elastic balls such as rubber, the propagation speed is slower, but the duration of collisions is longer, so the Hertzian solution still applies. The error introduced by the limited speed of the force propagation biases the Hertzian solution towards the simple solution because the collisions are not affected as much by the inertia of the balls that are further away.

Identically shaped balls help the pressure waves converge on the contact point of the last ball: at the initial strike point one pressure wave goes forward to the other balls while another goes backward to reflect off the opposite side of the first ball, and then it follows the first wave, being exactly one ball's diameter behind. The two waves meet up at the last contact point because the first wave reflects off the opposite side of the last ball and it meets up at the last contact point with the second wave. Then they reverberate back and forth like this about 10 times until the first ball stops connecting with the second ball. Then the reverberations reflect off the contact point between the second and third balls, but they still converge at the last contact point, until the last ball is ejected —but this is a lessening of a wavefront with each reflection.

Effect of different types of balls

[edit]Using different types of material does not change the action as long as the material is efficiently elastic. The size of the spheres does not change the results unless the increased weight exceeds the elastic limit of the material. If the solid balls are too large, energy is being lost as heat, because the elastic limit increases with the radius raised to the power 1.5, but the energy which had to be absorbed and released increases as the cube of the radius. Making the contact surfaces flatter can overcome this to an extent by distributing the compression to a larger amount of material but it can introduce an alignment problem. Steel is better than most materials because it allows the simple solution to apply more often in collisions after the first strike, its elastic range for storing energy remains good despite the higher energy caused by its weight, and the higher weight decreases the effect of air resistance.[citation needed]

Uses

[edit]The most common application is that of a desktop executive toy. Another use is as an educational physics demonstration, as an example of conservation of momentum and conservation of energy.

History

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2024) |

The principle demonstrated by the device, the law of impacts between bodies, was first demonstrated by the French physicist Abbé Mariotte in the 17th century.[1][8] His work on the topic was first presented to the French Academy of Sciences in 1671; it was published in 1673 as Traité de la percussion ou choc des corps ("Treatise on percussion or shock of bodies").[9]

Newton acknowledged Mariotte's work, along with Wren, Wallis and Huygens as the pioneers of experiments on the collisions of pendulum balls, in his Principia.

Christiaan Huygens used pendulums to study collisions. His work, De Motu Corporum ex Percussione (On the Motion of Bodies by Collision) published posthumously in 1703, contains a version of Newton's first law and discusses the collision of suspended bodies including two bodies of equal mass with the motion of the moving body being transferred to the one at rest.

There is much confusion over the origins of the modern Newton's cradle. Marius J. Morin has been credited as being the first to name and make this popular executive toy.[citation needed] However, in early 1967, an English actor, Simon Prebble, coined the name "Newton's cradle" (now used generically) for the wooden version manufactured by his company, Scientific Demonstrations Ltd.[10] After some initial resistance from retailers, they were first sold by Harrods of London, thus creating the start of an enduring market for executive toys.[citation needed] Later a very successful chrome design for the Carnaby Street store Gear was created by the sculptor and future film director Richard Loncraine.[citation needed]

The largest cradle device in the world was designed by MythBusters and consisted of five one-ton concrete and steel rebar-filled buoys suspended from a steel truss.[citation needed] The buoys also had a steel plate inserted in between their two-halves to act as a "contact point" for transferring the energy; this cradle device did not function well because concrete is not elastic so most of the energy was lost to a heat buildup in the concrete. A smaller-scale version constructed by them consists of five 15-centimetre (6 in) chrome steel ball bearings, each weighing 15 kilograms (33 lb), and is nearly as efficient as a desktop model.

The cradle device with the largest-diameter collision balls on public display was visible for more than a year in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, at the retail store American Science and Surplus (see photo). Each ball was an inflatable exercise ball 66 cm (26 in) in diameter (encased in steel rings), and was supported from the ceiling using extremely strong magnets. It was dismantled in early August 2010 due to maintenance concerns.[citation needed]

In popular culture

[edit]Newton's cradle appears in some films, often as a trope on the desk of a lead villain such as Paul Newman's role in The Hudsucker Proxy, Magneto in X-Men, and the Kryptonians in Superman II. It was used to represent the unyielding position of the NFL towards head injuries in Concussion.[11] It has also been used as a relaxing diversion on the desk of lead intelligent/anxious/sensitive characters such as Henry Winkler's role in Night Shift, Dustin Hoffman's role in Straw Dogs, and Gwyneth Paltrow's role in Iron Man 2. It was featured more prominently as a series of clay pots in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, and as a row of 1968 Eero Aarnio bubble chairs with scantily clad women in them in Gamer.[12] In Storks, Hunter, the CEO of Cornerstore, has one not with balls, but with little birds. Newton's cradle is an item in Nintendo's Animal Crossing where it is referred to as "executive toy".[13] In 2017, an episode of the Omnibus podcast, featuring Jeopardy! champion Ken Jennings and musician John Roderick, focused on the history of Newton's cradle.[14] Newton's cradle is also featured on the desk of Deputy White House Communications Director Sam Seaborn in The West Wing. In the Futurama episode "The Day the Earth Stood Stupid", professor Hubert Farnsworth is shown with his head in a Newton's cradle and saying he's a genius as Philip J. Fry walks by.

Progressive rock band Dream Theater uses the cradle as imagery in album art of their 2005 release Octavarium. Rock band Jefferson Airplane used the cradle on the 1968 album Crown of Creation as a rhythm device to create polyrhythms on an instrumental track.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- Galilean cannon

- Pendulum wave – another demonstration with pendulums swinging in parallel without collision

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Newton's Cradle". Harvard Natural Sciences Lecture Demonstrations. Harvard University. 27 February 2019.

- ^ Palermo, Elizabeth (28 August 2013). "How Does Newton's Cradle Work?". Live Science.

- ^ Gauld, Colin F. (August 2006). "Newton's Cradle in Physics Education". Science & Education. 15 (6): 597–617. Bibcode:2006Sc&Ed..15..597G. doi:10.1007/s11191-005-4785-3. S2CID 121894726.

- ^ Herrmann, F.; Seitz, M. (1982). "How does the ball-chain work?" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 50 (11): 977–981. Bibcode:1982AmJPh..50..977H. doi:10.1119/1.12936. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Lovett, D. R.; Moulding, K. M.; Anketell-Jones, S. (1988). "Collisions between elastic bodies: Newton's cradle". European Journal of Physics. 9 (4): 323. Bibcode:1988EJPh....9..323L. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/9/4/015. S2CID 250904041.

- ^ Hutzler, Stefan; Delaney, Gary; Weaire, Denis; MacLeod, Finn (2004). "Rocking Newton's Cradle" (PDF). American Journal of Physics. 72 (12): 1508–1516. Bibcode:2004AmJPh..72.1508H. doi:10.1119/1.1783898. hdl:1885/95080.C F Gauld (2006), Newton's cradle in physics education, Science & Education, 15, 597–617

- ^ Hinch, E.J.; Saint-Jean, S. (1999). "The fragmentation of a line of balls by an impact" (PDF). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A. Vol. 455. pp. 3201–3220.

- ^ Wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Edme Mariotte

- ^ Traité de la percussion ou choc des corps

- ^ Schulz, Chris (17 January 2012). "How Newton's Cradles Work". HowStuffWorks. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ Concussion – Cinemaniac Reviews Archived 11 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "13 Icons of Modern Design in Movies". Style Essentials. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ Animal Crossing Official Game Guide by Nintendo Power. Nintendo.

- ^ Omnibus: Newton's Cradle (Entry 835.1C1311)

Literature

[edit]- Herrmann, F. (1981). "Simple explanation of a well-known collision experiment". American Journal of Physics. 49 (8): 761. Bibcode:1981AmJPh..49..761H. doi:10.1119/1.12407.

- B. Brogliato: Nonsmooth Mechanics. Models, Dynamics and Control, Springer, 2nd Edition, 1999.

External links

[edit]- Simanek, Donald (2020) [2001]. "Newton's Cradle". Lock Haven University. Archived from the original on 9 October 2004.

- Uncoupled simple pendulums of monotonically increasing lengths (Jun 9, 2010). Harvard Natural Sciences Lecture Demonstrations on YouTube