Neural pathway

In neuroanatomy, a neural pathway is the connection formed by axons that project from neurons to make synapses onto neurons in another location, to enable neurotransmission (the sending of a signal from one region of the nervous system to another). Neurons are connected by a single axon, or by a bundle of axons known as a nerve tract, or fasciculus.[1] Shorter neural pathways are found within grey matter in the brain, whereas longer projections, made up of myelinated axons, constitute white matter.

In the hippocampus, there are neural pathways involved in its circuitry including the perforant pathway, that provides a connectional route from the entorhinal cortex[2] to all fields of the hippocampal formation, including the dentate gyrus, all CA fields (including CA1),[3] and the subiculum.

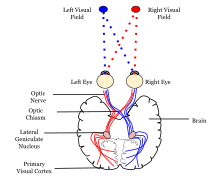

Descending motor pathways of the pyramidal tracts travel from the cerebral cortex to the brainstem or lower spinal cord.[4][5] Ascending sensory tracts in the dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway (DCML) carry information from the periphery to the cortex of the brain.

Naming

[edit]

The first named pathways are evident to the naked eye even in a poorly preserved brain, and were named by the great anatomists of the Renaissance using cadaver material.[citation needed] Examples of these include the great commissures of the brain such as the corpus callosum (Latin, "hard body"; not to be confused with the Latin word "colossus" – the "huge" statue), anterior commissure, and posterior commissure.[citation needed] Further examples include the pyramidal tract, crus cerebri (Latin, "leg of the brain"), and cerebellar peduncles (Latin, "little foot of the cerebellum").[citation needed] Note that these names describe the appearance of a structure but give no information on its function, location, etc.[citation needed]

Later, as neuroanatomical knowledge became more sophisticated, the trend was toward naming pathways by their origin and termination.[citation needed] For example, the nigrostriatal pathway runs from the substantia nigra (Latin, "black substance") to the corpus striatum (Latin, "striped body").[citation needed] This naming can extend to include any number of structures in a pathway, such that the cerebellorubrothalamocortical pathway originates in the cerebellum, synapses in the red nucleus ("ruber" in Latin), on to the thalamus, and finally terminating in the cerebral cortex.[citation needed]

Sometimes, these two naming conventions coexist. For example, the name "pyramidal tract" has been mainly supplanted by lateral corticospinal tract in most texts.[citation needed] Note that the "old" name was primarily descriptive, evoking the pyramids of antiquity, from the appearance of this neural pathway in the medulla oblongata.[citation needed] The "new" name is based primarily on its origin (in the primary motor cortex, Brodmann area 4) and termination (onto the alpha motor neurons of the spinal cord).[citation needed]

In the cerebellum, one of the two major pathways is that of the mossy fibers. Mossy fibers project directly to the deep nuclei, but also give rise to the following pathway: mossy fibers → granule cells → parallel fibers → Purkinje cells → deep nuclei. The other main pathway is from the climbing fibers and these project to Purkinje cells and also send collaterals directly to the deep nuclei.[6]

Functional aspects

[edit]

In general, neurons receive information either at their dendrites or cell bodies. The axon of a nerve cell is, in general, responsible for transmitting information over a relatively long distance. Therefore, most neural pathways are made up of axons.[citation needed] If the axons have myelin sheaths, then the pathway appears bright white because myelin is primarily lipid.[citation needed] If most or all of the axons lack myelin sheaths (i.e., are unmyelinated), then the pathway will appear a darker beige color, which is generally called grey.[citation needed]

Some neurons are responsible for conveying information over long distances. For example, motor neurons, which travel from the spinal cord to the muscle, can have axons up to a meter in length in humans. The longest axon in the human body belongs to the Sciatic Nerve and runs from the great toe to the base of the spinal cord. These are archetypal examples of neural pathways.[citation needed]

Basal ganglia pathways and dopamine

[edit]Neural pathways in the basal ganglia in the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop, are seen as controlling different aspects of behaviour. This regulation is enabled by the dopamine pathways. It has been proposed that the dopamine system of pathways is the overall organiser of the neural pathways that are seen to be parallels of the dopamine pathways.[7] Dopamine is provided both tonically and phasically in response to the needs of the neural pathways.[7]

Major neural pathways

[edit]- Arcuate fasciculus

- Cerebral peduncle

- Corpus callosum

- Pyramidal tracts – corticospinal and corticobulbar tracts

- Medial forebrain bundle

- Dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway

- Retinohypothalamic tract is a photic neural input pathway involved in the circadian rhythms

See also

[edit]- Direct pathway of movement

- Indirect pathway of movement

- Reflex arc

- Systems neuroscience

- Nerve tract

- Neural circuit

- Nerve plexus

References

[edit]- ^ Moore, Keith; Dalley, Arthur (2005). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (5th ed.). LWW. p. 47. ISBN 0-7817-3639-0.

A bundle of nerve fibers (axons) connecting neighboring or distant nuclei of the CNS is a tract.

- ^ Witter, Menno P.; Naber, Pieterke A.; Van Haeften, Theo; Machielsen, Willem C.M.; Rombouts, Serge A.R.B.; Barkhof, Frederik; Scheltens, Philip; Lopes Da Silva, Fernando H. (2000). "Cortico-hippocampal communication by way of parallel parahippocampal-subicular pathways". Hippocampus. 10 (4): 398–410. doi:10.1002/1098-1063(2000)10:4<398::AID-HIPO6>3.0.CO;2-K. PMID 10985279. S2CID 25432455.

- ^ Vago, David R.; Kesner, Raymond P. (2008). "Disruption of the direct perforant path input to the CA1 subregion of the dorsal hippocampus interferes with spatial working memory and novelty detection". Behavioural Brain Research. 189 (2): 273–83. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2008.01.002. PMC 2421012. PMID 18313770.

- ^ Purves, Dale (2011). Neuroscience (5. ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer. pp. 375–378. ISBN 9780878936953.

- ^ Purves, Dale; Augustine, George J.; Fitzpatrick, David; Katz, Lawrence C.; LaMantia, Anthony-Samuel; McNamara, James O.; Williams, S. Mark (1 January 2001). Damage to Descending Motor Pathways: The Upper Motor Neuron Syndrome. Sinauer Associates.

- ^ Llinas RR, Walton KD, Lang EJ (2004). "Ch. 7 Cerebellum". In Shepherd GM (ed.). The Synaptic Organization of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515955-1.

- ^ a b Hong, Simon (2013). "Dopamine system: manager of neural pathways". Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 7: 854. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2013.00854. PMC 3856400. PMID 24367324.