HMS Neptune (1909)

Neptune before 1914

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | St Vincent class |

| Succeeded by | Colossus class |

| Completed | 1 |

| Scrapped | 1 |

| History | |

| Name | Neptune |

| Namesake | Neptune |

| Ordered | 14 December 1908 |

| Builder | HM Dockyard, Portsmouth |

| Laid down | 19 January 1909 |

| Launched | 30 September 1909 |

| Completed | January 1911 |

| Commissioned | 11 January 1911 |

| Out of service | November 1921 |

| Fate | Sold for scrap, September 1922 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Type | Dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement | 19,680 long tons (20,000 t) (normal) |

| Length | 546 ft (166.4 m) (o/a) |

| Beam | 85 ft (25.9 m) |

| Draught | 28 ft 6 in (8.7 m) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 4 × shafts; 2 × steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph) |

| Range | 6,330 nmi (11,720 km; 7,280 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Complement | 756–813 (1914) |

| Armament |

|

| Armour | |

HMS Neptune was a dreadnought battleship built for the Royal Navy in the first decade of the 20th century, the sole ship of her class. She was the first British battleship to be built with superfiring guns. Shortly after her completion in 1911, she carried out trials of an experimental fire-control director and then became the flagship of the Home Fleet. Neptune became a private ship in early 1914 and was assigned to the 1st Battle Squadron.

The ship became part of the Grand Fleet when it was formed shortly after the beginning of the First World War in August 1914. Aside from participating in the Battle of Jutland in May 1916, and the inconclusive action of 19 August several months later, her service during the war generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea. Neptune was deemed obsolete after the war and was reduced to reserve before being sold for scrap in 1922 and subsequently broken up.

Background and description

[edit]

The launch of Dreadnought in 1906 precipitated a naval arms race when Germany accelerated its naval construction plans in response. Despite this sudden expansion of another nation's fleet, the British Admiralty felt secure in the knowledge that Germany would have only four modern capital ships in commission by 1910, while the Royal Navy would have eleven. Accordingly, they proposed the construction of only a single battleship and a battlecruiser in the 1908–1909 naval budget that they sent to the government in December. The Liberals, committed to reducing military expenditures and increasing social welfare spending, wished to cut the budget by £1,340,000 below the previous year's budget, but were ultimately persuaded not to do so after the Prime Minister, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman, was thoroughly briefed on each part of the budget in February 1908. The debates over the budget in March were heated; critics were dissatisfied with the number of ships being built, arguing that the Government was too complacent about the superiority of the Royal Navy over the Imperial German Navy, but they were satisfied when H. H. Asquith, Chancellor of the Exchequer, filling in for the fatally ill Prime Minister, announced that the government was prepared to build as many dreadnoughts as required to negate any possible German superiority as of the end of 1911.[1]

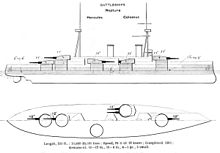

Neptune was an improved version of the preceding St Vincent class with additional armour and the armament rearranged for greater efficiency. She was the first British dreadnought that differed in her gun turret layout from Dreadnought. Unlike the earlier ships, her wing turrets were staggered "en echelon" so all five turrets could shoot on the broadside, although in practise the blast damage to the superstructure and boats made this impractical except in an emergency. This was done to match the 10-gun broadside of the latest foreign designs like the American Delaware class, although the all-centreline turret configuration of the American ships eliminated the blast problems that compromised the effectiveness of the "en echelon" arrangement. Neptune was also the first British dreadnought to be equipped with superfiring turrets, in an effort to shorten the ship and reduce costs. A further saving in length was achieved by siting the ship's boats on girders over the two wing turrets to reduce the length of the vessel. The drawback to this arrangement was that if the girders were damaged during combat, they could fall onto the turrets, immobilising them. The bridge was also situated above the conning tower, which similarly risked being obscured if the bridge collapsed.[2]

Neptune had an overall length of 546 feet (166.4 m), a beam of 85 feet (25.9 m),[3] and a deep draught of 28 feet 6 inches (8.7 m).[4] She displaced 19,680 long tons (20,000 t) at normal load and 23,123 long tons (23,494 t) at deep load. The ship had a metacentric height of 6.5 feet (2.0 m) at deep load. Her crew numbered about 756 officers and ratings upon completion and 813 in 1914.[5]

The ship was powered by two sets of Parsons direct-drive steam turbines, each of which was housed in a separate engine room. The outer propeller shafts were coupled to the high-pressure turbines and these exhausted into low-pressure turbines which drove the inner shafts. The turbines used steam from eighteen Yarrow boilers at a working pressure of 235 psi (1,620 kPa; 17 kgf/cm2). They were rated at 25,000 shaft horsepower (19,000 kW) and gave Neptune a maximum speed of 21 knots (39 km/h; 24 mph). She carried a maximum of 2,710 long tons (2,753 t) of coal and an additional 790 long tons (803 t) of fuel oil that was sprayed on the coal to increase its burn rate. This gave her a range of 6,330 nautical miles (11,720 km; 7,280 mi) at a cruising speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph).[6]

Armament

[edit]

Neptune was equipped with ten 50-calibre breech-loading (BL) 12-inch (305 mm) Mark XI guns in five hydraulically powered twin-gun turrets, three along the centreline and the remaining two as wing turrets. The centreline turrets were designated 'A', 'X' and 'Y', from front to rear, and the port and starboard wing turrets were 'P' and 'Q' respectively.[5] The guns had a maximum elevation of +20° which gave them a range of 21,200 yards (19,385 m). They fired 850-pound (386 kg) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,825 ft/s (861 m/s) at a rate of two rounds per minute.[7] The ship carried 100 shells per gun.[5]

Neptune was the first British dreadnought with her secondary armament of sixteen 50-calibre BL four-inch (102 mm) Mark VII guns installed in unshielded single mounts in the superstructure.[8][Note 1] This change was made to address the problems that plagued the turret-roof locations used in earlier battleships. Notably, the exposed guns were difficult to work when the main armament was in action as was replenishing their ammunition. Furthermore, the guns could not be centrally controlled to coordinate fire at the most dangerous targets.[11] The guns had a maximum elevation of +15° which gave them a range of 11,400 yd (10,424 m). They fired 31-pound (14.1 kg) projectiles at a muzzle velocity of 2,821 ft/s (860 m/s).[12] They were provided with 150 rounds per gun. Four quick-firing three-pounder (1.9 in (47 mm)) Hotchkiss saluting guns were also carried. The ships were equipped with three 18-inch (450 mm) submerged torpedo tubes, one on each broadside and another in the stern, for which 18 torpedoes were provided.[5]

Fire control

[edit]

The control positions for the main armament were located in the spotting tops at the head of the fore and mainmasts. Data from a nine-foot (2.7 m) Barr and Stroud coincidence rangefinder located at each control position was input into a Dumaresq mechanical computer and electrically transmitted to Vickers range clocks located in the transmitting station located beneath each position on the main deck, where it was converted into elevation and deflection data for use by the guns. The target's data was also graphically recorded on a plotting table to assist the gunnery officer in predicting the movement of the target. The turrets, transmitting stations, and control positions could be connected in almost any combination.[13]

Neptune was the first British dreadnought to be built with a gunnery director, albeit an experimental prototype designed by Vice-Admiral Sir Percy Scott. This was mounted on the foremast, underneath the spotting top and electrically provided data to the turrets via pointer on a dial, which the turret crewmen only had to follow. The director layer fired the guns simultaneously which aided in spotting the shell splashes and minimised the effects of the roll on the dispersion of the shells.[14] The ship's director was later replaced as a new one was ordered in 1913 and installed by May 1916.[15]

Additional nine-foot rangefinders, protected by armoured hoods, were added for each gun turret in late 1914.[16] Furthermore, the ship was fitted with Mark I Dreyer Fire-control Tables by early 1916 in each transmission station that combined the functions of the Dumaresq and the range clock.[17]

Armour

[edit]Neptune had a waterline belt of Krupp cemented armour that was 10 inches (254 mm) thick between the fore and aftmost barbettes that reduced to 2.5 inches (64 mm) before it reached the ships' ends. It covered the side of the hull from the middle deck down to 4 feet 4 inches (1.3 m) below the waterline where it thinned to 8 inches (203 mm) amidships. Above this was a strake of 8-inch armour. The forward oblique 5-inch (127 mm) bulkheads connected the amidships portion of waterline and upper armour belts once they reached the outer portions of the forward barbette. Similarly the aft bulkhead connected the armour belts to the rearmost barbette, although it was 8 inches thick. The three centreline barbettes were protected by armour 9 inches (229 mm) thick above the main deck and thinned to 5 inches (127 mm) below it. The wing barbettes were similar except that they had 10 inches of armour on their outer faces. The gun turrets had 11-inch (279 mm) faces and sides with 3-inch roofs.[5]

The three armoured decks ranged in thickness from 1.25 to 3 inches (32 to 76 mm) with the greater thicknesses outside the central armoured citadel. The front and sides of the conning tower were protected by 11-inch plates, although the rear and roof were 8 inches and 3 inches thick respectively. The torpedo control tower aft had 3-inch sides and a 2-inch roof. Neptune had two longitudinal anti-torpedo bulkheads that ranged in thickness from 1 to 3 inches (25 to 76 mm) and extended from the forward end of 'A' barbette to the end of 'Y' magazine. She was the first British dreadnought to protect her boiler uptakes with 1-inch armour plates.[18] The compartments between the boiler rooms were used as coal bunkers.[19]

Modifications

[edit]Gun shields were fitted to the forward four-inch guns after September 1913 and the upper forward four-inch guns were enclosed. In 1914–1915, the upper amidships four-inch guns were enclosed, the forward boat girder was removed and a three-inch (76 mm) anti-aircraft (AA) gun was added on the quarterdeck. Approximately 50 long tons (51 t) of deck armour was added after the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. By early 1917, four guns had been removed from the aft superstructure and a single four-inch AA gun had been added, for a total of a dozen four-inch guns. The stern torpedo tube was removed in 1917–1918 as was the aft spotting top. A high-angle rangefinder was fitted on the remaining spotting top and a flying-off platform was installed on the 'A' turret in 1918.[20]

Construction and career

[edit]

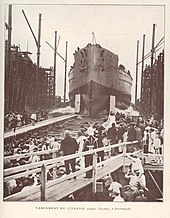

Neptune, named after the Roman god of the sea,[21] was ordered on 14 December 1908.[22] She was laid down at HM Dockyard, Portsmouth on 19 January 1909, launched on 30 September and completed in January 1911[10] at the cost of £1,668,916, including her armament.[8] The ship was commissioned on 19 January 1911 for trials with Scott's experimental gunnery director that lasted until 11 March and were witnessed by Rear-Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, commander of the Atlantic Fleet. Neptune relieved Dreadnought as the flagship of the Home Fleet and of the 1st Division on 25 March and then participated in the Coronation Fleet Review at Spithead on 24 June. On 1 May 1912, the 1st Division was renamed the 1st Battle Squadron (BS); Neptune was relieved as the squadron's flagship on 22 June. The ship participated in the Parliamentary Naval Review on 9 July at Spithead. Neptune became a private ship on 10 March 1914 when she was replaced by Iron Duke as the flagship of the Home Fleet and rejoined the 1st BS.[22]

First World War

[edit]Between 17 and 20 July 1914 Neptune took part in a test mobilisation and fleet review as part of the British response to the July Crisis. Arriving in Portland on 27 July, she was ordered to proceed with the rest of the Home Fleet to Scapa Flow two days later[5] to safeguard the fleet from a possible German surprise attack.[23] In August 1914, following the outbreak of the First World War, the Home Fleet was reorganised as the Grand Fleet, and placed under the command of Admiral Jellicoe.[24] Most of it was briefly based (22 October to 3 November) at Lough Swilly, Ireland, while the defences at Scapa were strengthened. On the evening of 22 November 1914, the Grand Fleet conducted a fruitless sweep in the southern half of the North Sea; Neptune stood with the main body in support of Vice-Admiral David Beatty's 1st Battlecruiser Squadron. The fleet was back in port in Scapa Flow by 27 November[25] and the ship began a refit on 11 December.[22]

Neptune's refit had concluded by the evening of 23 January 1915 as she joined the rest of the Grand Fleet when it sailed in support of Beatty's battlecruisers,[26] but the fleet was too far away participate in the ensuing Battle of Dogger Bank the following day. On 7–10 March, the Grand Fleet made a sweep in the northern North Sea, during which it conducted training manoeuvres.[Note 2] Another such cruise took place on 16–19 March; while returning home after the conclusion of the exercises, Neptune was unsuccessfully attacked by the German submarine SM U-29.[27] While manoeuvring for another attack, the submarine was spotted by Dreadnought which rammed and cut it in half. There were no survivors.[28] On 11 April, the Grand Fleet, including Neptune,[29] made a patrol in the central North Sea and returned to port on 14 April; another patrol in the area took place on 17–19 April, followed by gunnery drills off the Shetland Islands on 20–21 April.[30]

The Grand Fleet conducted sweeps into the central North Sea on 17–19 May and 29–31 May without encountering any German vessels. During 11–14 June the fleet practised gunnery and battle exercises west of Shetland,[31] and trained off Shetland three days later. On 2–5 September, the fleet went on another cruise in the northern end of the North Sea, conducting gunnery drills, and spent the rest of the month performing numerous training exercises. The ship, together with the majority of the Grand Fleet, made another sweep into the North Sea from 13 to 15 October. Almost three weeks later, Neptune participated in another fleet training operation west of Orkney during 2–5 November.[32]

The fleet departed for a cruise in the North Sea on 26 February 1916; Jellicoe had intended to use the Harwich Force to sweep the Heligoland Bight, but bad weather prevented operations in the southern North Sea. As a result, the operation was confined to the northern end of the sea. Another sweep began on 6 March, but had to be abandoned the following day as the weather grew too severe for the escorting destroyers. On the night of 25 March, Neptune and the rest of the fleet sailed from Scapa Flow to support Beatty's battlecruisers and other light forces raiding the German Zeppelin base at Tondern. By the time the Grand Fleet approached the area on 26 March, the British and German forces had already disengaged and a strong gale threatened the light craft, so the fleet was ordered to return to base. On 21 April, the Grand Fleet conducted a demonstration off Horns Reef to distract the Germans while the Imperial Russian Navy relaid its defensive minefields in the Baltic Sea.[33] During the night of 22/23 April, Neptune was accidentally rammed by the neutral merchant ship SS Needvaal in thick fog, but the battleship was only lightly damaged.[22] The fleet returned to Scapa Flow on 24 April and refuelled before proceeding south in response to intelligence reports that the Germans were about to launch a raid on Lowestoft, but arrived in the area only after the Germans had withdrawn. On 2–4 May, the fleet made another demonstration off Horns Reef to keep German attention focused on the North Sea.[34]

Battle of Jutland

[edit]

The German High Seas Fleet, composed of sixteen dreadnoughts, six pre-dreadnoughts and supporting ships, departed the Jade Bight early on the morning of 31 May in an attempt to lure out and destroy a portion of the Grand Fleet. The High Seas Fleet sailed in concert with Rear Admiral Franz von Hipper's five battlecruisers. The Royal Navy's Room 40 had intercepted and decrypted German radio traffic containing plans of the operation. In response the Admiralty ordered the Grand Fleet, totalling some 28 dreadnoughts and 9 battlecruisers, to sortie the night before to cut off and destroy the High Seas Fleet.[35]

On 31 May, Neptune, under the command of Captain Vivian Bernard, was assigned to the 5th Division of the 1st BS and was the nineteenth ship from the head of the battle line after deployment.[22] During the first stage of the general engagement, the ship fired two salvos from her main guns at a barely visible battleship at 18:40.[Note 3] Around the time that the High Seas Fleet was reversing course beginning at 18:55 to re-engage the Grand Fleet, Neptune fired one salvo at the crippled light cruiser SMS Wiesbaden with unknown effect. After the turn the ships of the 1st BS were the closest ones to the Germans and, at approximately 19:10, she fired four salvos at the battlecruiser SMS Derfflinger, claiming two hits, although neither can be confirmed. Shortly afterwards, the ship fired her main and secondary guns at enemy destroyers without result and then had to turn away to dodge three torpedoes. This was the last time Neptune fired her guns during the battle. She expended a total of 48 twelve-inch shells (21 high explosive and 27 common pointed, capped) and 48 shells from her four-inch guns during the battle.[36]

Subsequent activity

[edit]After the battle, the ship was transferred to the 4th Battle Squadron.[22] The Grand Fleet sortied on 18 August to ambush the High Seas Fleet while it advanced into the southern North Sea, but a series of miscommunications and mistakes prevented Jellicoe from intercepting the German fleet before it returned to port. Two light cruisers were sunk by German U-boats during the operation, prompting Jellicoe to decide to not risk the major units of the fleet south of 55° 30' North due to the prevalence of German submarines and mines. The Admiralty concurred and stipulated that the Grand Fleet would not sortie unless the German fleet was attempting an invasion of Britain or there was a strong possibility it could be forced into an engagement under suitable conditions.[37]

On 22 April 1918, the High Seas Fleet sailed north for the last time in an unsuccessful attempt to intercept a convoy to Norway, and had to turn back two days later after the battlecruiser SMS Moltke suffered engine damage. The Grand Fleet sortied from Rosyth on the 24th when the operation was discovered, but was unable to catch the Germans.[38] Neptune was present at Rosyth when the German fleet surrendered on 21 November and was reduced to reserve there on 1 February 1919 as she was thoroughly obsolete in comparison to the latest dreadnoughts. The ship was listed for disposal in March 1921 and was sold for scrap to Hughes Bolckow in September 1922. She was towed to Blyth, Northumberland on 22 September to begin demolition.[22]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Sources disagree on the number and composition of the secondary armament. Burt gives only a dozen 4-inch guns and also lists a 12-pounder (three-inch (76 mm)) gun.[5] No other source lists the 12 pounder, and all others concur on the number of 4 inchers. While Parkes does not identify the exact type of weapon, he does say they were 50-calibre guns. Preston also does not identify the gun, but claims that they were quick firers. Preston claims that the guns were BL 4-inch Mark VIII guns. Friedman shows the BL Mark VIII as a 40-calibre gun and says the 50-calibre BL Mark VII gun armed all the early dreadnoughts.[4][8][9][10]

- ^ In his 1919 book, Jellicoe generally named only specific ships when they were undertaking individual actions. Usually he referred to the Grand Fleet as a whole, or by squadrons and, unless otherwise specified, this article assumes that Neptune is participating in the activities of the Grand Fleet.

- ^ The times used in this section are in UT, which is one hour behind CET, which is often used in German works.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Marder, pp. 135–139

- ^ Brown, pp. 38–40; Burt, pp. 105, 107, 110; Friedman 2015, pp. 105–107, 109; Parkes, p. 510

- ^ Friedman (2015), p. 419

- ^ a b Preston (1972), p. 126

- ^ a b c d e f g Burt, p. 112

- ^ Burt, pp. 31, 64, 112–113

- ^ Friedman (2011), pp. 62–63

- ^ a b c Parkes, p. 509

- ^ Friedman (2011), pp. 97–99

- ^ a b Preston (1985), p. 25

- ^ Burt, p. 110

- ^ Friedman (2011), pp. 97–98

- ^ Brooks (1995), pp. 40–41

- ^ Brooks (2005), p. 48

- ^ Brooks (1996), p. 166

- ^ Admiralty Weekly Order No. 455 of 6 October 1914, referenced in footnote 32, "H.M.S. Neptune (1909)". The Dreadnought Project. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Brooks (2005), pp. 157–158, 175

- ^ Burt, pp. 110, 112–113

- ^ Friedman (2015), p. 107

- ^ Burt, pp. 113–115

- ^ Silverstone, pp. 253–54

- ^ a b c d e f g Burt, p. 116

- ^ Massie, p. 19

- ^ Preston (1985), p. 32

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 163–165

- ^ Monograph No. 12, p. 224

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 194–196, 206–207

- ^ Burt, p. 38

- ^ Monograph No. 29, p. 186

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 211–212

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 217, 218–219, 221–222

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 228, 243, 246, 250, 253

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 271, 275, 279–280, 284, 286

- ^ Jellicoe, pp. 286–290

- ^ Tarrant, pp. 54–55, 57–58

- ^ Campbell, pp. 156, 202, 205, 207, 210, 212, 349, 358; Tarrant, p. 151

- ^ Halpern, pp. 330–332

- ^ Newbolt, pp. 235–238

Bibliography

[edit]- Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery and the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-40788-5.

- Brooks, John (1995). "The Mast and Funnel Question: Fire-control Positions in British Dreadnoughts". In Roberts, John (ed.). Warship 1995. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 40–60. ISBN 0-85177-654-X.

- Brooks, John (1996). "Percy Scott and the Director". In McLean, David; Preston, Antony (eds.). Warship 1996. London: Conway Maritime Press. pp. 150–170. ISBN 0-85177-685-X.

- Brown, David K. (1999). The Grand Fleet: Warship Design and Development 1906–1922. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-315-X.

- Burt, R. A. (1986). British Battleships of World War One. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-863-7.

- Campbell, N. J. M. (1986). Jutland: An Analysis of the Fighting. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-324-5.

- Friedman, Norman (2015). The British Battleship 1906–1946. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-225-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Halpern, Paul G. (1995). A Naval History of World War I. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-352-4.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet, 1914–1916: Its Creation, Development, and Work. New York: George H. Doran Company. OCLC 13614571.

- Marder, Arthur J. (2013) [1961]. From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow: The Royal Navy in the Fisher Era 1904–1919. Vol. I: The Road to War 1904–1914. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-259-1.

- Massie, Robert K. (2003). Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-679-45671-6.

- Monograph No. 12: The Action of Dogger Bank – 24th January 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. III. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1921. pp. 209–226. OCLC 220734221.

- Monograph No. 29: Home Waters–Part IV.: From February to July 1915 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. XIII. The Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1925. p. 186. OCLC 220734221.

- Newbolt, Henry (1996) [1931]. Naval Operations. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents. Vol. V. Nashville, Tennessee: Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-255-1.

- Parkes, Oscar (1990) [1966]. British Battleships, Warrior 1860 to Vanguard 1950: A History of Design, Construction, and Armament (New & rev. ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-075-4.

- Preston, Antony (1972). Battleships of World War I: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Battleships of All Nations 1914–1918. New York: Galahad Books. ISBN 0-88365-300-1.

- Preston, Antony (1985). "Great Britain and Empire Forces". In Gray, Randal (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. pp. 1–104. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Silverstone, Paul H. (1984). Directory of the World's Capital Ships. New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0-88254-979-0.

- Tarrant, V. E. (1999) [1995]. Jutland: The German Perspective: A New View of the Great Battle, 31 May 1916. London: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-917-8.

External links

[edit]- HMS Neptune on the Dreadnought Project Technical material on the weaponry and fire control for the ships

- Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project – HMS Neptune Crew List