Longan

| Longan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Sapindaceae |

| Genus: | Dimocarpus |

| Species: | D. longan

|

| Binomial name | |

| Dimocarpus longan | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

| Longan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

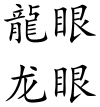

"Longan" in Traditional (top) and Simplified (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍眼 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙眼 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | 'dragon eye' | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dimocarpus longan, commonly known as the longan (/ˈlɒŋɑːn/) and dragon's eye, is a tropical tree species that produces edible fruit.[3] It is one of the better-known tropical members of the soapberry family Sapindaceae, to which the lychee and rambutan also belong.[3] The fruit of the longan is similar to that of the lychee, but is less aromatic in taste.[4]

The longan (from Vietnamese long nhãn[5] or Cantonese lùhng ngáahn 龍眼, literally 'dragon eye'), is so named because the black seed within the shelled fruit creates the appearance of an eyeball. The plant is native to tropical Asia and China.[6]

Description

[edit]Depending upon climate and soil type the tree may grow to over 30 metres (100 ft)[7] in height, but it typically stands 9–12 m (30–40 ft) in height and the crown is round.[3][8] The trunk is 80 cm (2+1⁄2 ft) thick[3] with corky bark.[8] The branches are long and thick, typically drooping.[3]

The leaves are oblong and blunt-tipped, usually 10–20 centimetres (4–8 in) long and 5 cm (2 in) wide.[3] The leaves are pinnately compounded and alternate.[8] There are 6 to 9 pairs of leaflets per leaf[8] and the upper surface is wavy and a dark, glossy-green.[3]

The longan tree produces light-yellow inflorescences at the end of branches.[3] The inflorescence is commonly called a panicle; they can be 10–46 cm (4–18 in) long, and widely branched.[8] The small flowers have 5 to 6 sepals and petals that are brownish-yellow.[8] The flower has a two-lobed pistil and 8 stamen. There are three flower types, distributed throughout the panicle;[3] staminate (functionally male), pistillate (functionally female), and hermaphroditic flowers.[8] Flowering occurs as a progression.[8]

The fruit are circular and about 2.5 cm (1 in) wide; they hang in drooping clusters. The shell is tan, thin, and leathery with tiny hairs;[8] when firm, it can be squeezed (as in the cracking of a sunflower seed) to shell the fruit.[citation needed] The flesh is translucent, and the seed is large and black with a circular white spot at the base.[3][8] This gives the illusion of an eye.[3] The flesh has a musky, sweet taste, which can be compared to the flavor of lychee fruit.[3] The seed is round, hard, and has a lacquered appearance.[citation needed]

The longan tree is somewhat sensitive to frost. While the species prefers temperatures that do not typically fall below 4.5 °C (40 °F), it can withstand brief temperature drops to about −2 °C (28 °F).[9] Longan trees prefer sandy soil with mild levels of acidity and organic matter.[3] Longans usually bear fruit slightly later than lychees.[10]

Taxonomy

[edit]The longan is believed to originate from the mountain range between Myanmar and southern China. Other reported origins include Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, upper Myanmar, north Thailand, Kampuchea (more commonly known as Cambodia), north Vietnam and New Guinea.[11]

Its earliest record of existence draws back to the Han dynasty in 200 BCE. The emperor had demanded lychee and longan trees to be planted in his palace gardens in Shaanxi, but the plants failed. Four hundred years later, longan trees flourished in other parts of China like Fujian and Guangdong, where longan production soon became an industry.[12]

Later on, due to immigration and the growing demand for nostalgic foods, the longan tree was officially introduced to Australia in the mid-1800s, Thailand in the late-1800s, and Hawaii and Florida in the 1900s. The warm, sandy-soiled conditions allowed for the easy growth of longan trees. This jump-started the longan industry in these locations.[12]

Despite its long success in China, the longan is considered to be a relatively new fruit to the world. It has only been acknowledged outside of China in the last 250 years.[12] The first European acknowledgment of the fruit was recorded by João de Loureiro, a Portuguese Jesuit botanist, in 1790. The first entry resides in his collection of works, Flora Cochinchinensis.[5][4]

Subspecies

[edit]Plants of the World Online lists:[13]

- D. longan var. echinatus Leenhouts (Borneo, Philippines)

- D. longan var. longetiolatus Leenhouts (Viet Nam)

- D. longan subsp. malesianus Leenh. (widespread SE Asia)

- D. longan var. obtusus (Pierre) Leenh. (Indo-China)

Conservation

[edit]The wild longan population have been decimated considerably by large-scale logging in the past, and the species used to be listed as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List. If left alone, longan tree stumps will resprout and the listing was upgraded to Near Threatened in 1998. Recent field data are inadequate for a contemporary IUCN assessment.[1]

Diseases

[edit]Plant based diseases can affect both longan fruits and their trees, and the severity of these diseases can range from harmless cosmetic damage to rendering to the fruit inedible.

The most prevalent disease among longan plants is witch's broom, which can be found in all major longan-producing Asian territories, including China, Thailand, and Vietnam.[14] Witch's broom deforms longan skin, and at times causes the plant to prematurely drop its fruit, similar to the Phytophthora palmivora.[15]

Another common disease that longan trees can carry is the aptly named longan decline, which is largely prevalent in Thailand, with reports finding that it could affect up to 40% of longan trees alone.[16] Affected trees are more vulnerable to common tree pests and algae, and often bear low-quality fruit unworthy of yield.[16]

Algal spot is another plant disease that can affect longan plants and trees. Common among tropical fruits, the disease mainly takes form as red-orange algae that can appear on a fruit-bearing tree's leaves or branches.[17]Algal spot on longan plants, like many other tropical fruits, is caused by Cephaleuros virescens.[18]

An oomycete disease that causes blight on leaves and foliage of a plant and affects the related lychee, Phytophthora palmivora, can also appear on both longan plants and fruit,[19] particularly in the Thailand region. When affecting longan, it can create brown spots on the fruit in an erratic fashion, and can also cause longan to drop prematurely from the plant. Early symptoms can also include a dark necrosis on the plant itself.[20]

Stem-end rot is a disease common amongst litchi and longan, and causes browning and rot on the stem of the fruit. Longan also suffer from various decay-accelerating fungi.[16]

An oomycete disease that affects the related lychee, Phytophthora litchii, also afflicts D. longan.[19]

Cultivation

[edit]Currently, longan crops are grown in southern China, Taiwan, northern Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, India, Sri Lanka, the Philippines,[11] Bangladesh,[21] Mauritius, the United States, and Australia.[11]

Growth

[edit]Longan, like its sister fruit lychee, thrives in humid areas or places with high rainfall, and can grow on most types of soil that does not induce issues with water drainage.[22] Ample temperatures are also instrumental in longan growth: while longan can resist small stretches of cool temperatures, they can be damaged or killed in longer stretches of temperatures as high as −2 degrees Celsius. Younger plants tend to be more vulnerable to the cold than those more mature.[22][23]

A peeled longan fruit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 251 kJ (60 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

15.14 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | n/a | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 1.1 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.1 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1.31 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Threonine | 0.034 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isoleucine | 0.026 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Leucine | 0.054 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lysine | 0.046 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Methionine | 0.013 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phenylalanine | 0.030 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tyrosine | 0.025 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Valine | 0.058 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arginine | 0.035 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Histidine | 0.012 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alanine | 0.157 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aspartic acid | 0.126 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glutamic acid | 0.209 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Glycine | 0.042 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Proline | 0.042 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Serine | 0.048 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 83 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[24] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[25] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Harvest

[edit]During harvest, pickers must climb ladders to carefully remove branches of fruit from longan trees. Longan fruit remain fresher if still attached to the branch, so efforts are made to prevent the fruit from detaching too early. Mechanical picking would damage the delicate skin of the fruit, so the preferred method is to harvest by hand. Knives and scissors are the most commonly used tools.[26]

Fruit is picked early in the day to minimize water loss and to prevent high heat exposure, which would be damaging. The fruit is then placed into either plastic crates or bamboo baskets and taken to packaging houses, where the fruit undergo a series of checks for quality. The packaging houses are well-ventilated and shaded to prevent further decay. The process of checking and sorting are performed by workers instead of machinery. Any fruit that is split, under-ripe, or decaying is disposed of. The remaining healthy fruit is then prepared and shipped to markets.[27]

Many companies add preservatives to canned longan. Regulations control the preserving process. The only known preservative added to canned longan is sulfur dioxide, to prevent discoloration.[27] Fresh longan that is shipped worldwide is exposed to sulfur fumigation. Tests have shown that sulfur residues remain on the fruit skin, branches, and leaves for a few weeks. This violates many countries' limits on fumigation residue, and efforts have been made to reduce this amount.[27]

Distribution

[edit]Longan is found commonly in most of Asia, primarily in mainland China, Taiwan, Vietnam and Thailand. China, the main longan-producing country in the world, produced about 1.9 million metric tons (2.1 million short tons) of longan in 2015–2017, accounting for 70% of the world's longan production and more than 50% of the world's longan plots.[28] Vietnam and Thailand produced around 500 and 980 thousand metric tons (550 and 1,080 thousand short tons), respectively.[29] Like Vietnam, Thailand's economy relies heavily on the cultivation and shipments of longan as well as lychee. This increase in the production of longan reflects recent interest in exotic fruits in other parts of the world. However, the majority of the demand comes from Asian communities in North America, Europe and Australia.[27]

Yield

[edit]While longan yields average out to 2 to 5 tonnes per hectare, there have been observed yields of up to 19.5 tonnes per ha in Israel.[30]

Advancements in selective breeding have allowed scientists to find a strain of longan containing a "high proportion of aborted seeds" at the end of a thirty-year breeding program in 2001.[31] Studies in 2015 that aimed to aid longan breeding efforts discovered that −20 degrees Celsius is the optimal temperature for long-term storage of longan pollen, a key ingredient in enabling longan breeding programs.[32]

Uses

[edit]Nutrition

[edit]Raw longan fruit is 83% water, 15% carbohydrates, 1% protein, and contains negligible fat (table). In a 100 g (3.5 oz) reference amount, raw longan supplies 60 calories of food energy, 93% of the Daily Value (DV) of vitamin C, 11% DV of riboflavin, and no other micronutrients in appreciable quantities (table).

Culinary

[edit]The fruit is sweet, juicy, and succulent in superior agricultural varieties. The seed and the peel are not consumed. Apart from being eaten raw like other fruits, longan fruit is also often used in Asian soups, snacks, desserts, and sweet-and-sour foods, either fresh or dried, and sometimes preserved and canned in syrup. The taste is different from lychees; while longan has a drier sweetness similar to dates, lychees are often messily juicy with a more tropical, grape-like sour sweetness.

Dried longan are often used in Chinese cuisine and Chinese sweet dessert soups. In Chinese food therapy and herbal medicine, it is believed to have an effect on relaxation.[33] In contrast with the fresh fruit, which is juicy and white, the flesh of dried longans is dark brown to almost black.

Once fermented, it can be made into longan wine.

See also

[edit]- Lansium parasiticum, the langsat or lanzones

- Talisia esculenta, a visually similar fruit from South America

References

[edit]- ^ a b Barstow, M. (2022). "Dimocarpus longan". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2022: e.T32399A67808402. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Dimocarpus longan". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 5 September 2016 – via The Plant List. Note that this website has been superseded by World Flora Online

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Morton, Julia F. (1987). Longan; In: Fruits of Warm Climates. W. Lafayette, IN, USA: NewCrop, Center for New Crops and Plant Products, Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, Purdue University. pp. 259–262.

- ^ a b Pham, V.T.; Herrero, M. (2016). "Fruiting pattern in longan, Dimocarpus longan: from pollination to aril development" (PDF). Annals of Applied Biology. 169 (3): 357–368. doi:10.1111/aab.12306. hdl:10261/135703.

- ^ a b Loureiro, J. de (1790). Flora Cochinchinensis (in Latin). Vol. I. Lisbon: Ulyssipone.

- ^ "Dimocarpus longan". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Crane, Jonathan H.; Balerdi, Carlos F.; Sargent, Steven A.; Maguire, Ian (November 1978). "Longan Growing in the Florida Home Landscape". University of Florida (2016 ed.). Retrieved 4 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Crane, Jonathan; Balerdi, Carlos; Sarge, Steven; Maguire, Ian (2015). "Longan Growing in the Florida Home Landscape". IFAS University of Florida. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Herbst, S. & R. (2009). The Deluxe Food Lover's Companion. Barron's Educational Series – via Credo Reference.

- ^ Jiang, Yueming; Zhang, Zhaoqi (November 2002). "Postharvest biology and handling of longan fruit (Dimocarpus longan Lour.)". Postharvest Biology and Technology. 26 (3): 241–252. doi:10.1016/s0925-5214(02)00047-9.

- ^ a b c Lim, T.K. (2013). "Dimocarpus longan subsp. longan var. longan". Edible Medicinal And Non-Medicinal Plants: Volume 6, Fruits. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 18–29. ISBN 978-94-007-5628-1.

- ^ a b c Menzel, C.; Waite, G.K.; Mitra, S.K. (2005). Litchi and Longan: Botany, Production and Uses. CAB International. ISBN 9781845930226 – via ProQuest ebrary.

- ^ "Dimocarpus longan Lour. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science". Plants of the World Online.

- ^ Olesen, T.; Menzel, C. M.; Wiltshire, N.; McConchie, C. A. (2002). "Flowering and shoot elongation of lychee in eastern Australia". Australian Journal of Agricultural Research. 53 (8): 977. doi:10.1071/ar01179. ISSN 0004-9409.

- ^ So, Vera; Zee, S.-Y. (September 1972). "A New Virus of Longan (Euphoria longana Lam.) in Hong Kong". PANS Pest Articles & News Summaries. 18 (3): 283–285. doi:10.1080/09670877209411804. ISSN 0030-7793.

- ^ a b c Menzel, C. M.; Waite, G. K., eds. (2005). Litchi and longan: botany, production and uses. doi:10.1079/9780851996967.0000. ISBN 9780851996967.

- ^ Visarathanonth, N. (December 1990). "A Survey of Some Temperate Fruit Diseases in Thailand". Acta Horticulturae (279): 609–618. doi:10.17660/actahortic.1990.279.67. ISSN 0567-7572.

- ^ Bache, Bryon (December 1994). "Compendium of Tropical Fruit Diseases, by R. C. Ploetz G. A. Zentmyer, W. T. Nishijima, K. G. Rohrbach & H. D. Ohr. viii + 88 pp. St Paul, Minnesota: American Phytopathological Society (1994). £30.00 (US) $37.00 (elsewhere) (paper back) ISBN 0 582 89054 162 0". The Journal of Agricultural Science. 123 (3): 419–420. doi:10.1017/s0021859600070520. ISSN 0021-8596.

- ^ a b Wang, Yan; Tyler, Brett M.; Wang, Yuanchao (8 September 2019). "Defense and Counterdefense During Plant-Pathogenic Oomycete Infection". Annual Review of Microbiology. 73 (1). Annual Reviews: 667–696. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-120022. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 31226025. S2CID 195259901.

- ^ Sittigul, C.; Pota, S.; Visitpanich, J.; Nualbunruang, P.; Sookchaoy, K. (January 2005). "The Brown Spot Disease of Longan in Thailand". Acta Horticulturae (665): 389–394. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2005.665.48. ISSN 0567-7572.

- ^ Khatun, MM; Karim, MR; Molla, MM; Khatun, MM; Rahman, MJ (2012). "Study on the physico-chemical characteristics of longan (Euphoria longana) germplasm". Bangladesh Journal of Agricultural Research. 37 (3): 441–447. doi:10.3329/bjar.v37i3.12087. ISSN 0258-7122.

- ^ a b Paull, R. E.; Duarte, O., eds. (2011). Tropical fruits, Volume 1. doi:10.1079/9781845936723.0000. ISBN 9781845936723.

- ^ Blancke, Rolf (17 March 2017). Tropical Fruits and Other Edible Plants of the World. doi:10.7591/9781501704284. ISBN 9781501704284.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 27 March 2024. Retrieved 28 March 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 9 May 2024. Retrieved 21 June 2024.

- ^ Siddiq, Muhammad (2012). Tropical and Subtropical Fruits: Postharvest Physiology, Processing and Packaging. John Wiley & Sons – via Google Books.

- ^ a b c d Menzel, C.; Waite, G.K.; Mitra, S.K. (2005). Litchi and Longan: Botany, Production and Uses. CAB International. ISBN 9781845930226 – via ProQuest ebrary.

- ^ Luo, Jun, Can-fang Zhou, and Zhong Wan. "Analysis on the development status of lychee industry in Guangdong province in 2010." Guangdong Agric Sci 4 (2011): 16-8.

- ^ Altendorf, Sabine (July 2018). "MINOR TROPICAL FRUITS Mainstreaming a niche market" (PDF). FAO. Retrieved 9 September 2020.

- ^ Lora, Jorge; Pham, Van The; Hormaza, José I. (2018), Al-Khayri, Jameel M.; Jain, Shri Mohan; Johnson, Dennis V. (eds.), "Genetics and Breeding of Fruit Crops in the Sapindaceae Family: Lychee (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) and Longan (Dimocarpus longan Lour.)", Advances in Plant Breeding Strategies: Fruits, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 953–973, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-91944-7_23, ISBN 978-3-319-91943-0, retrieved 5 October 2022

- ^ Huang, J.S.; Xu, X.D.; Zheng, S.Q.; Xu, J.H. (August 2001). "Selection for Aborted-Seeded Longan Cultivars". Acta Horticulturae (558): 115–118. doi:10.17660/actahortic.2001.558.14. ISSN 0567-7572.

- ^ Pham, V.T.; Herrero, M.; Hormaza, J.I. (December 2015). "Effect of temperature on pollen germination and pollen tube growth in longan ( Dimocarpus longan Lour.)". Scientia Horticulturae. 197: 470–475. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2015.10.007. hdl:10261/127752. ISSN 0304-4238.

- ^ Teeguarden, Ron. "Tonic Herbs That Every Qigong Practioner [sic] Should Know, Part 2". Qi Journal.

External links

[edit]- Longan Production in Asia from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations