Modern monetary theory

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

Modern monetary theory or modern money theory (MMT) is a heterodox[1] macroeconomic theory that describes currency as a public monopoly and unemployment as evidence that a currency monopolist is overly restricting the supply of the financial assets needed to pay taxes and satisfy savings desires.[2] According to MMT, governments do not need to worry about accumulating debt since they can pay interest by printing money. MMT argues that the primary risk once the economy reaches full employment is inflation, which acts as the only constraint on spending. MMT also argues that inflation can be controlled by increasing taxes on everyone, to reduce the spending capacity of the private sector.[3][4][verification needed][5]

MMT is opposed to the mainstream understanding of macroeconomic theory and has been criticized heavily by many mainstream economists.[6][7][8][9] MMT is also strongly opposed by members of the Austrian school of economics, with Murray Rothbard stating that MMT practices are equivalent to "counterfeiting" and that government control of the money supply will inevitably lead to hyperinflation.[10]

Principles

MMT's main tenets are that a government that issues its own fiat money:

- Can pay for goods, services, and financial assets without a need to first collect money in the form of taxes or debt issuance in advance of such purchases

- Cannot be forced to default on debt denominated in its own currency

- Is limited in its money creation and purchases only by inflation, which accelerates once the real resources (labour, capital and natural resources) of the economy are utilized at full employment

- Should strengthen automatic stabilisers to control demand-pull inflation,[11] rather than relying upon discretionary tax changes

- Issues bonds as a monetary policy device, rather than as a funding device

- Uses taxation to provide the fiscal space to spend without causing inflation and also to give a value to the currency. Taxation is often said in MMT not to fund the spending of a currency-issuing government, but without it no real spending is of course possible.[12]

The first four MMT tenets do not conflict with mainstream economics understanding of how money creation and inflation works. However, MMT economists disagree with mainstream economics about the fifth tenet: the impact of government deficits on interest rates.[13][14][15][16][17]

History

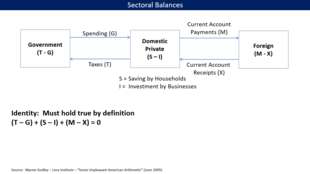

MMT synthesizes ideas from the state theory of money of Georg Friedrich Knapp (also known as chartalism) and the credit theory of money of Alfred Mitchell-Innes, the functional finance proposals of Abba Lerner, Hyman Minsky's views on the banking system[18] and Wynne Godley's sectoral balances approach.[15]

Knapp wrote in 1905 that "money is a creature of law", rather than a commodity.[19] Knapp contrasted his state theory of money with the Gold Standard view of "metallism", where the value of a unit of currency depends on the quantity of precious metal it contains or for which it may be exchanged. He said that the state can create pure paper money and make it exchangeable by recognizing it as legal tender, with the criterion for the money of a state being "that which is accepted at the public pay offices".[19]

The prevailing view of money was that it had evolved from systems of barter to become a medium of exchange because it represented a durable commodity which had some use value,[20] but proponents of MMT such as Randall Wray and Mathew Forstater said that more general statements appearing to support a chartalist view of tax-driven paper money appear in the earlier writings of many classical economists,[21] including Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, J. S. Mill, Karl Marx, and William Stanley Jevons.[22]

Alfred Mitchell-Innes wrote in 1914 that money exists not as a medium of exchange but as a standard of deferred payment, with government money being debt the government may reclaim through taxation.[23] Innes said:

Whenever a tax is imposed, each taxpayer becomes responsible for the redemption of a small part of the debt which the government has contracted by its issues of money, whether coins, certificates, notes, drafts on the treasury, or by whatever name this money is called. He has to acquire his portion of the debt from some holder of a coin or certificate or other form of government money, and present it to the Treasury in liquidation of his legal debt. He has to redeem or cancel that portion of the debt ... The redemption of government debt by taxation is the basic law of coinage and of any issue of government 'money' in whatever form.

— Alfred Mitchell-Innes, "The Credit Theory of Money", The Banking Law Journal

Knapp and "chartalism" are referenced by John Maynard Keynes in the opening pages of his 1930 Treatise on Money[24] and appear to have influenced Keynesian ideas on the role of the state in the economy.[21]

By 1947, when Abba Lerner wrote his article "Money as a Creature of the State", economists had largely abandoned the idea that the value of money was closely linked to gold.[25] Lerner said that responsibility for avoiding inflation and depressions lay with the state because of its ability to create or tax away money.[25]

Hyman Minsky seemed to favor a chartalist approach to understanding money creation in his Stabilizing an Unstable Economy,[18] while Basil Moore, in his book Horizontalists and Verticalists,[26] lists the differences between bank money and state money.

In 1996, Wynne Godley wrote an article on his sectoral balances approach, which MMT draws from.[15]

Economists Warren Mosler, L. Randall Wray, Stephanie Kelton,[27] Bill Mitchell and Pavlina R. Tcherneva are largely responsible for reviving the idea of chartalism as an explanation of money creation; Wray refers to this revived formulation as neo-chartalism.[28]

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell's book Free Money (1996)[29] describes in layman's terms the essence of chartalism.

Pavlina R. Tcherneva has developed the first mathematical framework for MMT[30] and has largely focused on developing the idea of the job guarantee.

Bill Mitchell, professor of economics and Director of the Centre of Full Employment and Equity (CoFEE) at the University of Newcastle in Australia, coined the term 'modern monetary theory'.[31] In their 2008 book Full Employment Abandoned, Mitchell and Joan Muysken use the term to explain monetary systems in which national governments have a monopoly on issuing fiat currency and where a floating exchange rate frees monetary policy from the need to protect foreign exchange reserves.[32]

Some contemporary proponents, such as Wray, place MMT within post-Keynesian economics, while MMT has been proposed as an alternative or complementary theory to monetary circuit theory, both being forms of endogenous money, i.e., money created within the economy, as by government deficit spending or bank lending, rather than from outside, perhaps with gold. In the complementary view, MMT explains the "vertical" (government-to-private and vice versa) interactions, while circuit theory is a model of the "horizontal" (private-to-private) interactions.[33][34]

By 2013, MMT had attracted a popular following through academic blogs and other websites.[35]

In 2019, MMT became a major topic of debate after U.S. Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said in January that the theory should be a larger part of the conversation.[36] In February 2019, Macroeconomics became the first academic textbook based on the theory, published by Bill Mitchell, Randall Wray, and Martin Watts.[4][37] MMT became increasingly used by chief economists and Wall Street executives for economic forecasts and investment strategies. The theory was also intensely debated by lawmakers in Japan, which was planning to raise taxes after years of deficit spending.[38][39]

In June 2020, Stephanie Kelton's MMT book The Deficit Myth became a New York Times bestseller.[40]

In 2020 the Sri Lankan Central Bank, under the governor W. D. Lakshman, cited MMT as a justification for adopting unconventional monetary policy, which was continued by Ajith Nivard Cabraal. This has been heavily criticized and widely cited as causing accelerating inflation and exacerbating the Sri Lankan economic crisis.[41][42] MMT scholars Stephanie Kelton and Fadhel Kaboub maintain that the Sri Lankan government's fiscal and monetary policy bore little resemblance to the recommendations of MMT economists.[43]

Theoretical approach

In sovereign financial systems, banks can create money, but these "horizontal" transactions do not increase net financial assets because assets are offset by liabilities. According to MMT advocates, "The balance sheet of the government does not include any domestic monetary instrument on its asset side; it owns no money. All monetary instruments issued by the government are on its liability side and are created and destroyed with spending and taxing or bond offerings."[44] In MMT, "vertical money" enters circulation through government spending. Taxation and its legal tender enable power to discharge debt and establish fiat money as currency, giving it value by creating demand for it in the form of a private tax obligation. In addition, fines, fees, and licenses create demand for the currency. This currency can be issued by the domestic government or by using a foreign, accepted currency.[45][46] An ongoing tax obligation, in concert with private confidence and acceptance of the currency, underpins the value of the currency. Because the government can issue its own currency at will, MMT maintains that the level of taxation relative to government spending (the government's deficit spending or budget surplus) is in reality a policy tool that regulates inflation and unemployment, and not a means of funding the government's activities by itself. The approach of MMT typically reverses theories of governmental austerity. The policy implications of the two are likewise typically opposed.[47]

Vertical transactions

MMT labels a transaction between a government entity (public sector) and a non-government entity (private sector) as a "vertical transaction". The government sector includes the treasury and central bank. The non-government sector includes domestic and foreign private individuals and firms (including the private banking system) and foreign buyers and sellers of the currency.[37]

Interaction between government and the banking sector

MMT is based on an account of the "operational realities" of interactions between the government and its central bank, and the commercial banking sector, with proponents like Scott Fullwiler arguing that understanding reserve accounting is critical to understanding monetary policy options.[49]

A sovereign government typically has an operating account with the country's central bank. From this account, the government can spend and also receive taxes and other inflows.[33] Each commercial bank also has an account with the central bank, by means of which it manages its reserves (that is, money for clearing and settling interbank transactions).[50]

When a government spends money, its central bank debits its Treasury's operating account and credits the reserve accounts of the commercial banks. The commercial bank of the final recipient will then credit up this recipient's deposit account by issuing bank money. This spending increases the total reserve deposits in the commercial bank sector. Taxation works in reverse: taxpayers have their bank deposit accounts debited, along with their bank's reserve account being debited to pay the government; thus, deposits in the commercial banking sector fall.[13]

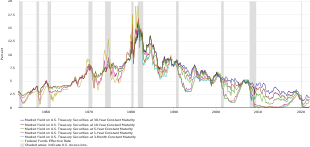

Government bonds and interest rate maintenance

Virtually all central banks set an interest rate target, and most now establish administered rates to anchor the short-term overnight interest rate at their target. These administered rates include interest paid directly on reserve balances held by commercial banks, a discount rate charged to banks for borrowing reserves directly from the central bank, and an Overnight Reverse Repurchase (ON RRP) facility rate paid to banks for temporarily forgoing reserves in exchange for Treasury securities.[51] The latter facility is a type of open market operation to help ensure interest rates remain at a target level. According to MMT, the issuing of government bonds is best understood as an operation to offset government spending rather than a requirement to finance it.[49]

In most countries, commercial banks' reserve accounts with the central bank must have a positive balance at the end of every day; in some countries, the amount is specifically set as a proportion of the liabilities a bank has, i.e., its customer deposits. This is known as a reserve requirement. At the end of every day, a commercial bank will have to examine the status of their reserve accounts. Those that are in deficit have the option of borrowing the required funds from the Central Bank, where they may be charged a lending rate (sometimes known as a discount window or discount rate) on the amount they borrow. On the other hand, the banks that have excess reserves can simply leave them with the central bank and earn a support rate from the central bank. Some countries, such as Japan, have a support rate of zero.[52]

Banks with more reserves than they need will be willing to lend to banks with a reserve shortage on the interbank lending market. The surplus banks will want to earn a higher rate than the support rate that the central bank pays on reserves; whereas the deficit banks will want to pay a lower interest rate than the discount rate the central bank charges for borrowing. Thus, they will lend to each other until each bank has reached their reserve requirement. In a balanced system, where there are just enough total reserves for all the banks to meet requirements, the short-term interbank lending rate will be in between the support rate and the discount rate.[52]

Under an MMT framework where government spending injects new reserves into the commercial banking system, and taxes withdraw them from the banking system,[13] government activity would have an instant effect on interbank lending. If on a particular day, the government spends more than it taxes, reserves have been added to the banking system (see vertical transactions). This action typically leads to a system-wide surplus of reserves, with competition between banks seeking to lend their excess reserves, forcing the short-term interest rate down to the support rate (or to zero if a support rate is not in place). At this point, banks will simply keep their reserve surplus with their central bank and earn the support rate.[53]

The alternate case is where the government receives more taxes on a particular day than it spends. Then there may be a system-wide deficit of reserves. Consequently, surplus funds will be in demand on the interbank market, and thus the short-term interest rate will rise towards the discount rate. Thus, if the central bank wants to maintain a target interest rate somewhere between the support rate and the discount rate, it must manage the liquidity in the system to ensure that the correct amount of reserves is on-hand in the banking system.[13]

Central banks manage liquidity by buying and selling government bonds on the open market. When excess reserves are in the banking system, the central bank sells bonds, removing reserves from the banking system, because private individuals pay for the bonds. When insufficient reserves are in the system, the central bank buys government bonds from the private sector, adding reserves to the banking system.

The central bank buys bonds by simply creating money – it is not financed in any way.[54] It is a net injection of reserves into the banking system. If a central bank is to maintain a target interest rate, then it must buy and sell government bonds on the open market in order to maintain the correct amount of reserves in the system.[55]

Horizontal transactions

MMT economists describe any transactions within the private sector as "horizontal" transactions, including the expansion of the broad money supply through the extension of credit by banks.

MMT economists regard the concept of the money multiplier, where a bank is completely constrained in lending through the deposits it holds and its capital requirement, as misleading.[56][57] Rather than being a practical limitation on lending, the cost of borrowing funds from the interbank market (or the central bank) represents a profitability consideration when the private bank lends in excess of its reserve or capital requirements (see interaction between government and the banking sector). Effects on employment are used as evidence that a currency monopolist is overly restricting the supply of the financial assets needed to pay taxes and satisfy savings desires.[58][44]

According to MMT, bank credit should be regarded as a "leverage" of the monetary base and should not be regarded as increasing the net financial assets held by an economy: only the government or central bank is able to issue high-powered money with no corresponding liability.[59] Stephanie Kelton said that bank money is generally accepted in settlement of debt and taxes because of state guarantees, but that state-issued high-powered money sits atop a "hierarchy of money".[60]

Foreign sector

Imports and exports

MMT proponents such as Warren Mosler say that trade deficits are sustainable and beneficial to the standard of living in the short term.[61] Imports are an economic benefit to the importing nation because they provide the nation with real goods. Exports, however, are an economic cost to the exporting nation because it is losing real goods that it could have consumed.[62] Currency transferred to foreign ownership, however, represents a future claim over goods of that nation.[citation needed]

Cheap imports may also cause the failure of local firms providing similar goods at higher prices, and hence unemployment, but MMT proponents label that consideration as a subjective value-based one, rather than an economic-based one: It is up to a nation to decide whether it values the benefit of cheaper imports more than it values employment in a particular industry.[62] Similarly a nation overly dependent on imports may face a supply shock if the exchange rate drops significantly, though central banks can and do trade on foreign exchange markets to avoid shocks to the exchange rate.[63]

Foreign sector and government

MMT says that as long as demand exists for the issuer's currency, whether the bond holder is foreign or not, governments can never be insolvent when the debt obligations are in their own currency; this is because the government is not constrained in creating its own fiat currency (although the bond holder may affect the exchange rate by converting to local currency).[64]

MMT does agree with mainstream economics that debt in a foreign currency is a fiscal risk to governments, because the indebted government cannot create foreign currency. In this case, the only way the government can repay its foreign debt is to ensure that its currency is continually in high demand by foreigners over the period that it wishes to repay its debt; an exchange rate collapse would potentially multiply the debt many times over asymptotically, making it impossible to repay. In that case, the government can default, or attempt to shift to an export-led strategy or raise interest rates to attract foreign investment in the currency. Either one negatively affects the economy.[65]

Policy implications

Economist Stephanie Kelton explained several points made by MMT in March 2019:[66][67]

- Under MMT, fiscal policy (i.e., government taxing and spending decisions) is the primary means of achieving full employment, establishing the budget deficit at the level necessary to reach that goal. In mainstream economics, monetary policy (i.e., Central Bank adjustment of interest rates and its balance sheet) is the primary mechanism, assuming there is some interest rate low enough to achieve full employment. Kelton said that "cutting interest rates is ineffective in a slump" because businesses, expecting weak profits and few customers, will not invest even at very low interest rates.

- Government interest expenses are proportional to interest rates, so raising rates is a form of stimulus (it increases the budget deficit and injects money into the private sector, other things being equal); cutting rates is a form of austerity.

- Achieving full employment can be administered via a centrally-funded job guarantee, which acts as an automatic stabilizer. When private sector jobs are plentiful, the government spending on guaranteed jobs is lower, and vice versa.

- Under MMT, expansionary fiscal policy, i.e., money creation to fund purchases, can increase bank reserves, which can lower interest rates. In mainstream economics, expansionary fiscal policy, i.e., debt issuance and spending, can result in higher interest rates, crowding out economic activity.

Economist John T. Harvey explained several of the premises of MMT and their policy implications in March 2019:[68]

- The private sector treats labor as a cost to be minimized, so it cannot be expected to achieve full employment without government creating jobs, too, such as through a job guarantee.

- The public sector's deficit is the private sector's surplus and vice versa, by accounting identity, which increased private sector debt during the Clinton-era budget surpluses.

- Creating money activates idle resources, mainly labor. Not doing so is immoral.

- Demand can be insensitive to interest rate changes, so a key mainstream assumption, that lower interest rates lead to higher demand, is questionable.

- There is a "free lunch" in creating money to fund government expenditure to achieve full employment. Unemployment is a burden; full employment is not.

- Creating money alone does not cause inflation; spending it when the economy is at full employment can.

MMT says that "borrowing" is a misnomer when applied to a sovereign government's fiscal operations, because the government is merely accepting its own IOUs, and nobody can borrow back their own debt instruments.[69] Sovereign government goes into debt by issuing its own liabilities that are financial wealth to the private sector. "Private debt is debt, but government debt is financial wealth to the private sector."[70]

In this theory, sovereign government is not financially constrained in its ability to spend; the government can afford to buy anything that is for sale in currency that it issues; there may, however, be political constraints, like a debt ceiling law. The only constraint is that excessive spending by any sector of the economy, whether households, firms, or public, could cause inflationary pressures.

MMT economists advocate a government-funded job guarantee scheme to eliminate involuntary unemployment. Proponents say that this activity can be consistent with price stability because it targets unemployment directly rather than attempting to increase private sector job creation indirectly through a much larger economic stimulus, and maintains a "buffer stock" of labor that can readily switch to the private sector when jobs become available. A job guarantee program could also be considered an automatic stabilizer to the economy, expanding when private sector activity cools down and shrinking in size when private sector activity heats up.[71]

MMT economists also say quantitative easing (QE) is unlikely to have the effects that its advocates hope for.[72] Under MMT, QE – the purchasing of government debt by central banks – is simply an asset swap, exchanging interest-bearing dollars for non-interest-bearing dollars. The net result of this procedure is not to inject new investment into the real economy, but instead to drive up asset prices, shifting money from government bonds into other assets such as equities, which enhances economic inequality. The Bank of England's analysis of QE confirms that it has disproportionately benefited the wealthiest.[73]

MMT economists say that inflation can be better controlled (than by setting interest rates) with new or increased taxes to remove extra money from the economy.[5] These tax increases would be on everyone, not just billionaires, since the majority of spending is by average Americans.[5]

Comparison of MMT with mainstream Keynesian economics

The examples and perspective in this article may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2020) |

MMT can be compared and contrasted with mainstream Keynesian economics in a variety of ways:[4][66][67]

| Topic | Mainstream Keynesian | MMT |

|---|---|---|

| Funding government spending | Advocates taxation and issuing bonds (debt) as preferred methods for funding government spending.[dubious – discuss] | Emphasizes that government fund spending by crediting bank accounts. |

| Purpose of taxation | To pay down debt from central banks loaned to the government at interest, which is spent into the economy and the taxpayer needs to repay.[dubious – discuss] | Primarily to drive up demand for currency. Secondary uses of taxation include lowering inflation, reducing income inequality, and discouraging bad behavior.[74] |

| Achieving full employment | Main strategy uses monetary policy; central bank has "dual mandate" of maximum employment and stable prices, but these goals are not always compatible. For example, much higher interest rates used to reduce inflation also caused high unemployment in the early 1980s.[75] | Main strategy uses fiscal policy; running a budget deficit large enough to achieve full employment through a job guarantee. |

| Inflation control | Driven by monetary policy; central bank sets interest rates consistent with a stable price level, sometimes setting a target inflation rate.[75] | Driven by fiscal policy; government increases taxes on everyone to remove money from private sector.[5] A job guarantee also provides a NAIBER, which acts as an inflation control mechanism. |

| Setting interest rates | Managed by central bank to achieve "dual mandate" of maximum employment and stable prices.[75] | Emphasizes that an interest rate target is not a potent policy.[66] The government may choose to maintain a zero interest-rate policy by not issuing public debt at all.[76] |

| Budget deficit impact on interest rates | At full employment, higher budget deficit can crowd out investment. | Deficit spending can drive down interest rates, encouraging investment and thus "crowding in" economic activity.[77] |

| Automatic stabilizers | Primary stabilizers are unemployment insurance and food stamps, which increase budget deficits in a downturn. | In addition to the other stabilizers, a job guarantee would increase deficits in a downturn.[71] |

Criticism

A 2019 survey of leading economists by the University of Chicago Booth's Initiative on Global Markets showed a unanimous rejection of assertions attributed by the survey to MMT: "Countries that borrow in their own currency should not worry about government deficits because they can always create money to finance their debt" and "Countries that borrow in their own currency can finance as much real government spending as they want by creating money".[78][79] Directly responding to the survey, MMT economist William K. Black said "MMT scholars do not make or support either claim."[80] Multiple MMT academics regard the attribution of these claims as a smear.[81]

The post-Keynesian economist Thomas Palley has stated that MMT is largely a restatement of elementary Keynesian economics, but prone to "over-simplistic analysis" and understating the risks of its policy implications.[82] Palley has disagreed with proponents of MMT who have asserted that standard Keynesian analysis does not fully capture the accounting identities and financial restraints on a government that can issue its own money. He said that these insights are well captured by standard Keynesian stock-flow consistent IS-LM models, and have been well understood by Keynesian economists for decades. He claimed MMT "assumes away the problem of fiscal–monetary conflict" – that is, that the governmental body that creates the spending budget (e.g. the legislature) may refuse to cooperate with the governmental body that controls the money supply (e.g., the central bank).[83] He stated the policies proposed by MMT proponents would cause serious financial instability in an open economy with flexible exchange rates, while using fixed exchange rates would restore hard financial constraints on the government and "undermines MMT's main claim about sovereign money freeing governments from standard market disciplines and financial constraints". Furthermore, Palley has asserted that MMT lacks a plausible theory of inflation, particularly in the context of full employment in the employer of last resort policy first proposed by Hyman Minsky and advocated by Bill Mitchell and other MMT theorists; of a lack of appreciation of the financial instability that could be caused by permanently zero interest rates; and of overstating the importance of government-created money. Palley concludes that MMT provides no new insights about monetary theory, while making unsubstantiated claims about macroeconomic policy, and that MMT has only received attention recently due to it being a "policy polemic for depressed times".[83]

Marc Lavoie has said that whilst the neochartalist argument is "essentially correct", many of its counter-intuitive claims depend on a "confusing" and "fictitious" consolidation of government and central banking operations,[17] which is what Palley calls "the problem of fiscal–monetary conflict".[83]

New Keynesian economist and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Economics, Paul Krugman, asserted MMT goes too far in its support for government budget deficits, and ignores the inflationary implications of maintaining budget deficits when the economy is growing.[84] Krugman accused MMT devotees as engaging in "calvinball" – a game from the comic strip Calvin and Hobbes in which the players change the rules at whim.[27] Austrian School economist Robert P. Murphy stated that MMT is "dead wrong" and that "the MMT worldview doesn't live up to its promises".[85] He said that MMT saying cutting government deficits erodes private saving is true "only for the portion of private saving that is not invested" and says that the national accounting identities used to explain this aspect of MMT could equally be used to support arguments that government deficits "crowd out" private sector investment.[85]

The chartalist view of money itself, and the MMT emphasis on the importance of taxes in driving money, is also a source of criticism.[17] In 2015, three MMT economists, Scott Fullwiler, Stephanie Kelton, and L. Randall Wray, addressed what they saw as the main criticisms being made.[15]

See also

- Everything bubble

- Friedman's k-percent rule - money supply should be increased at a fixed percentage

- Debt based monetary system[broken anchor] - monetary system where commercial banks create the new money as debt

References

- ^

- Chohan, Usman W. (6 April 2020). "Modern Monetary Theory (MMT): A General Introduction". CASS Working Papers on Economics & National Affairs. Social Science Research Network. SSRN 3569416. EC017UC (2020).

- Edwards, Sebastian (2019). "Modern monetary theory: Cautionary tales from Latin America". Cato Journal. 39 (3): 529. doi:10.36009/CJ.39.3.3. S2CID 195792372.

- Kosaka, Norihiko (6 August 2019). "The Heterodox Modern Monetary Theory and Its Challenges for Japan". Nippon. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Krugman, Paul (12 February 2019). "How Much Does Heterodoxy Help Progressives? (Wonkish)" (Opinion). The New York Times. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Raposo, Ines Goncalves (11 June 2019). "On Modern Monetary Theory". Bruegel. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Mosler, Warren. "Heterodox Views of Money and Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)" (PDF). Mosler Economics (blog).[self-published source]

- ^ Pressman, Steven; Smithin, John (30 November 2022). Debates in Monetary Macroeconomics: Tackling Some Unsettled Questions. Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-031-11240-9.

- ^ Wray, L. Randall (2015). Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 137–41, 199–206. ISBN 978-1-137-53990-8.

- ^ a b c Coy, Peter; Dmitrieva, Katia; Boesler, Matthew (21 March 2019). "Warren Buffett Hates It. AOC Is for It. A Beginner's Guide to Modern Monetary Theory". Bloomberg Businessweek.

- ^ a b c d Mackintosh, James (21 November 2021). "Modern Monetary Theory Isn't the Future. It's Here Now". Wall Street Journal.

But MMT prescribes that if tax rises are needed to slow demand, billionaires wouldn't be the target: The rest of us would. "It makes more sense to have a broad-based tax that would reduce demand across the broader economy, especially people who have a propensity to spend of 98%, which is the majority of Americans," Mr. [Randall] Wray said. Other MMT ideas have infiltrated their way into the heart of the establishment, but the idea that the government should raise taxes on ordinary Americans, let alone that it should do so to control inflation, is exceptionally unlikely to be accepted.

- ^ Krugmann, Paul (25 February 2019). "Running on MMT (wonkish)". The New York Times.

- ^ Mankiw, N. Gregory (2020). "A Skeptic's Guide to Modern Monetary Theory". AEA Papers and Proceedings. 110: 141–44. doi:10.1257/pandp.20201102. ISSN 2574-0768. S2CID 219804544.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (5 April 2019). "Modern Monetary Theory Finds an Embrace in an Unexpected Place: Wall Street". The New York Times.

To many mainstream economists, though, M.M.T. is a confused mishmash that proponents use to support their political objectives, whether big government programs like "Medicare for all" and the Green New Deal or smaller taxes. ... From this perspective, M.M.T. is a version of free-lunchonomics, leaving the next generation to pay for this generation's profligacy. Although several prominent mainstream economists have recently revised their thinking about the risks of large government debt, they continue to reject other tenets of M.M.T. At some point, they insist, if the government just creates money to pay the bills, hyperinflation will kick in.

- ^ Smialek, Jeanna (6 February 2019). "Is This What Winning Looks Like?". The New York Times.

The theory picked up some fervent followers but limited popular acceptance, charitably, and outright derision, uncharitably. Mainstream economists panned it as overly simplistic. Many were confused about what it was arguing. "I have heard pretty extreme claims attributed to that framework and I don't know whether that's fair or not," Jerome H. Powell, the Fed chair, said in 2019. "The idea that deficits don't matter for countries that can borrow in their own currency is just wrong."

- ^ Carney, John (27 December 2011). "Modern Monetary Theory and Austrian Economics". CNBC. Retrieved 17 April 2024.

- ^ Fullwiler, Scott; Grey, Rohan; Tankus, Nathan (1 March 2019). "An MMT response on what causes inflation". FT Alphaville. The Financial Times Ltd. Retrieved 27 April 2019.

- ^ Wray, L. Randall (15 May 2014). "WHAT ARE TAXES FOR? THE MMT APPROACH".

- ^ a b c d Bell, Stephanie (2000). "Do Taxes and Bonds Finance Government Spending?". Journal of Economic Issues. 34 (3): 603–620. doi:10.1080/00213624.2000.11506296. ISSN 0021-3624. JSTOR 4227588.

- ^ Sharpe, Timothy P. (13 October 2013). "A Modern Money Perspective on Financial Crowding-out". Review of Political Economy. 25 (4): 586–606. doi:10.1080/09538259.2013.837325. ISSN 0953-8259.

- ^ a b c d Fullwiler, Scott; Kelton, Stephanie; Wray, L. Randall (January 2012), "Modern Money Theory: A Response to Critics", Working Paper Series: Modern Monetary Theory – A Debate (PDF), Amherst, Massachusetts: Political Economy Research Institute, pp. 17–26, retrieved 7 May 2015

- ^ Fullwiler, Scott T. (2016) "The Debt Ratio and Sustainable Macroeconomic Policy", World Economic Review 7:12–42

- ^ a b c Marc Lavoie. "The monetary and fiscal nexus of neo-chartalism" (PDF).

- ^ a b Minsky, Hyman: Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, McGraw-Hill, 2008 (originally published 1986), ISBN 978-0-07-159299-4

- ^ a b Knapp, George Friedrich (1905), Staatliche Theorie des Geldes, Verlag von Duncker & Humblot

- ^ Marx, Karl (1867). "1: Commodities – Section 1: The Two Factors of a Commodity: Use-Value and Value (The Substance of Value and the Magnitude of Value)". Capital. Vol. I. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

The utility of a thing makes it a use value.

- ^ a b Wray, L. Randall (2000), The Neo-Chartalist Approach to Money, UMKC Center for Full Employment and Price Stability, archived from the original on 20 October 2019, retrieved 5 October 2009

- ^ Forstater, Mathew (2004), Tax-Driven Money: Additional Evidence from the History of Thought, Economic History, and Economic Policy (PDF), p. 3, archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2024, retrieved 9 February 2024

- ^ Mitchell-Innes, Alfred (1914). "The Credit Theory of Money". The Banking Law Journal. 31.

- ^ Keynes, John Maynard (1930). A Treatise on Money. pp. 4, 6

- ^ a b Lerner, Abba P. (May 1947). "Money as a Creature of the State". The American Economic Review. 37 (2).

- ^ Moore, Basil J.: Horizontalists and Verticalists: The Macroeconomics of Credit Money, Cambridge University Press, 1988, ISBN 978-0-521-35079-2

- ^ a b "Is modern monetary theory nutty or essential?". The Economist. 12 March 2019. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ "Marginal revolutionaries". The Economist. 31 December 2011.

... neo-chartalism, sometimes called 'Modern Monetary Theory' ...

- ^ Mitchell, Rodger Malcolm: Free Money – Plan for Prosperity, PGM International, Inc., paperback 2005, ISBN 978-0-9658323-1-1

- ^ Tcherneva, Pavlina R. "Monopoly Money: The State as a Price Setter" (PDF). www.modernmoneynetwork.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (18 February 2012). "Modern Monetary Theory is an unconventional take on economic strategy". The Washington Post. Washington, DC. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ Mitchell, William; Muysken, Joan (2008). Full Employment Abandoned: Shifting Sands and Policy Failures. Northampton, Massachusetts: Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-85898-507-7. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b Bill Mitchell (2 March 2009). "Deficit Spending 101 – Part 3"

- ^ Bill Mitchell (28 September 2009). "In the spirit of debate...my reply"

- ^ Lowrey, Annie (4 July 2013). "Warren Mosler, a Deficit Lover With a Following". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (16 April 2019). "Modern Monetary Theory, explained". Vox. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b Mitchell, William (2019). Macroeconomics. London: Red Globe. pp. 84–87. ISBN 978-1-137-61066-9. OCLC 967762036.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia (5 April 2019). "Modern Monetary Theory Finds an Embrace in an Unexpected Place: Wall Street". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Dooley, Ben (5 June 2019). "Modern Monetary Theory's Reluctant Poster Child: Japan". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ "Stephanie Kelton Cracks Best Seller List". SBU News. 26 June 2020. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Money printing continues as inflation soars". The Morning. Sri Lanka. 26 March 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "Printing money: Our way out in 2022 too?". The Morning. Sri Lanka. 8 January 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ "No, MMT Didn't Wreck Sri Lanka". 29 April 2022.

- ^ a b Tymoigne, Éric; Wray, L. Randall (November 2013). "Modern Money Theory 101: A Reply to Critics". Levy Economics Institute of Bard College. Working Paper No. 778.

- ^ Mosler, Warren. "Soft Currency Economics", January 1994

- ^ Tcherneva Pavlina R. "Chartalism and the tax-driven approach to money", in A Handbook of Alternative Monetary Economics, edited by Philip Arestis & Malcolm C. Sawyer, Elgar Publishing (2007), ISBN 978-1-84376-915-6

- ^ Singh, Devin P.; Thompson, Randal Joy; Curran, Kathleen A. (29 September 2021). Reimagining Leadership on the Commons: Shifting the Paradigm for a More Ethical, Equitable, and Just World. Emerald Group Publishing. ISBN 978-1-83909-526-9.

- ^ "An Update to the Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028". Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved November 12, 2018.

- ^ a b Fullwiler, Scott T. (2010). "Modern Monetary Theory - A Primer on the Operational Realities of the Monetary System". SSRN 1723198.

- ^ Meulendyke, Ann-Marie (1998). U.S. Monetary Policy and Financial Markets (PDF) (Report). Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- ^ Ihrig, Jane (August 2020). "The Fed's New Monetary Policy Tools". Economic Research Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis. Retrieved 26 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Unconventional monetary policies: an appraisal" by Claudio Borio and Piti Disyatat, Bank for International Settlements, November, 2009

- ^ Fullwiler, Scott T (1 December 2004). "Paying Interest on Reserve Balances: It's More Significant than You Think". SSRN 1723589.

- ^ Bell, Stephanie (1999), "Functional Finance: What, Why, and How?" (Working Paper No. 287), UMKC Center for Full Employment and Price Stability

- ^ Fullwiler, Scott T. (2007) "Interest Rates and Fiscal Sustainability," Journal of Economic Issues, 41:4, 1003–1042

- ^ Wray, L Randall: Money and Credit in Capitalist Economies: The Endogenous Money Approach, Edward Elgar Publishing, 1990 ISBN 1-85278-356-7 pp.149,179

- ^ Lavoie, Marc: Introduction to Post-Keynesian Economics, Palgrave MacMillan, 2006 ISBN 9780230626300 pp.60–73

- ^ Warren Mosler, ME/MMT: The Currency as a Public Monopoly Archived 28 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, IT: Uni BG.

- ^ "Money multiplier and other myths" Bill Mitchell, 21 April 2009

- ^ Kelton, Stephanie (Bell) (2001), "The Role of the State and the Hierarchy of Money" (PDF), Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25 (25): 149–163, doi:10.1093/CJE/25.2.149, S2CID 28281365, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2020

- ^ Mosler, Warren (2010). Seven Deadly Innocent Frauds (PDF). Valance. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-0-692-00959-8.

- ^ a b "Do current account deficits matter?" Bill Mitchell, 22 June 2010

- ^ Foreign Exchange Transactions and Holdings of Official Reserve Assets, Reserve Bank of Australia

- ^ "Modern monetary theory and inflation – Part 1" Bill Mitchell, 7 July 2010

- ^ "There is no financial crisis so deep that cannot be dealt with by public spending – still!" Bill Mitchell, 11 October 2010

- ^ a b c Kelton, Stephanie (1 March 2019). "Paul Krugman Asked Me About Modern Monetary Theory. Here Are 4 Answers". Bloomberg.

- ^ a b Kelton, Stephanie (4 March 2019). "The Clock Runs Down on Mainstream Keynesianism". Bloomberg.

- ^ Harvey, John T. "MMT: Sense Or Nonsense?". Forbes.

- ^ "Q:Why Does Government Issue Bonds? Randall Wray: Sovereign government really can't borrow, because what it is doing is accepting back its own IOUs. If you have given your IOU to your neighbor because you borrowed some sugar, could you borrow it back? No, you can't borrow back your own IOUs". Youtube.com. 23 November 2009. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- ^ Yeva Nersisyan & L. Randall Wray, "Does Excessive Sovereign Debt Really Hurt Growth? A Critique of This Time Is Different, by Reinhart and Rogoff," Levy Economics Institute (June, 2010), p. 15.

- ^ a b L. Randal Wray, "Job Guarantee," New Economic Perspectives (23 August 2009).

- ^ "Quantitative Easing". The Gower Initiative for Modern Money Studies. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ "Bank of England Working Paper Considers Monetary Policy's Effect on Inequality". Positive Money. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- ^ Wray, L. Randall (15 May 2014). "WHAT ARE TAXES FOR? THE MMT APPROACH".

- ^ a b c "FRB Richmond-Aaron Steelman-The Federal Reserves Dual Mandate: The Evolution of an Idea"-December 2011

- ^ Mitchell, William (3 September 2015). "There Is No Need to Issue Public Debt".

- ^ Kelton, Stephanie (21 February 2019). "Modern Monetary Theory Is Not a Recipe for Doom". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Modern Monetary Theory". www.igmchicago.org. 2019. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Bryan, Bob (14 March 2019). "A new survey shows that zero top US economists agreed with the basic principles of an economic theory supported by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez". Business Insider. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Black, William K. (14 March 2019). "The Day Orthodox Economists Lost Their Minds and Integrity". New Economic Perspectives.

- ^ Mitchell, Bill (19 March 2019). "Fake surveys and Groupthink in the economics profession". bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog - Bill Mitchell - Modern Monetary Theory.

- ^ Thomas Palley, Money, fiscal policy, and interest rates: A critique of Modern Monetary Theory (PDF)

- ^ a b c Thomas Palley (February 2014). "Modern money theory (MMT): the emperor still has no clothes" (PDF).

- ^ Paul Krugman (25 March 2011). "Deficits and the Printing Press (Somewhat Wonkish)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 26 March 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ a b Robert P. Murphy (9 May 2011). "The Upside-Down World of MMT". Ludwig von Mises Institute. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

![]() This article incorporates text by Yasuhito Tanaka available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text by Yasuhito Tanaka available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

Further reading

- Mitchell, Bill; Wray, L. Randall; Watts, Martin J. (February 2019), Macroeconomics, London: Macmillan Publishers, ISBN 978-1-137-61066-9

- Innes, A. Mitchell (1913), "What is Money?", The Banking Law Journal, archived from the original on 22 October 2016, retrieved 28 January 2009

- Lerner, Abba P. (1947), "Money as a Creature of the State", American Economic Review

- Wray, L. Randall (2000), The Neo-Chartalist Approach to Money, UMKC Center for Full Employment and Price Stability, archived from the original on 20 October 2019, retrieved 5 October 2009

- Wray, L. Randall (2001), The Endogenous Money Approach, UMKC Center for Full Employment and Price Stability, archived from the original on 15 March 2017, retrieved 5 October 2009

- Febrero, Eladio (2009), "Three difficulties with neo-chartalism" (PDF), Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 31 (3): 523–541, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.564.8770, doi:10.2753/PKE0160-3477310308, S2CID 154990728

- Mitchell, Bill (2009), The fundamental principles of modern monetary economics,

in "It's Hard Being a Bear (Part Six)? Good Alternative Theory?" (PDF)

{{citation}}: External link in|quote= - Wray, L. Randall (December 2010), Money, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College

- Mosler, Warren (March 2014), ME/MMT: The Currency as a Public Monopoly (PDF), University of Bergamo, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 February 2020, retrieved 24 January 2019

- Wray, L. Randall (2015). Modern Money Theory : A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 137–141, 199–206. ISBN 978-1-137-53990-8.

- Kelton, Stephanie (2020), The Deficit Myth, John Murray, ISBN 978-1-529-35252-8

- Tcherneva, Pavlina (2020), The Case for a Job Guarantee, Polity, ISBN 978-1-509-54210-9

External links

- January 2012: Modern Monetary Theory: A Debate (Brett Fiebiger critiques and Scott Fullwiler, Stephanie Kelton, L. Randall Wray respond; Political Economy Research Institute, Amherst, MA)

- June 2012: Knut Wicksell and origins of modern monetary theory (Lars Pålsson Syll)

- September 2020: Degrowth and MMT: A thought Experiment (Jason Hickel)

- The Modern Money Network is currently headquartered at Columbia University in the city of New York.

- October 2023: Finding The Money at IMDb is a documentary film about an underdog group of MMT economists on a mission to instigate a paradigm shift by flipping our understanding of the national debt, and the nature of money, upside down.