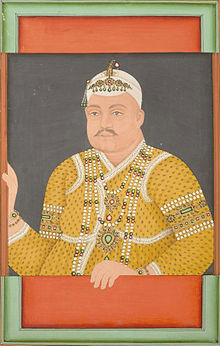

Nasir-ud-Daulah

| Farqunda Ali Khan | |

|---|---|

| Nizam-ul-Mulk | |

Nasir-ud-Daulah | |

| 4th Nizam of Hyderabad State | |

| Reign | 24 May 1829 – 16 May 1857 |

| Predecessor | Sikandar Jah |

| Successor | Afzal-ud-Daulah |

| Born | Mir Farqunda Ali Khan 25 April 1794 Bidar |

| Died | 16 May 1857 (aged 63) |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Dilawar-un-Nisa Begum[1] |

| Issue |

|

| House | Asaf Jahi |

| Father | Sikandar Jah |

| Mother | Fazilat-un-Nisa Begum |

| Religion | Islam |

Mir Farqunda Ali Khan (25 April 1794 – 16 May 1857) commonly known as Nasir-ud-Daulah, was fourth Nizam of Hyderabad, a princely state of British India, from 24 May 1829 until his death in 1857.

Born as Farqunda Ali Khan to Nizam Sikandar Jah and Fazilatunnisa Begum, Nasir-ud-Daulah ascended the throne in 1829. He inherited a financially weak kingdom. On his request, Lord William Bentinck withdrew all of the European superintendents of civil departments and followed a policy of non-intervention in the Nizam's affairs. The Nizam founded the Hyderabad Medical School in 1846; he also owed large debts to the Arabs, the Rohillas and the British, and in 1853 he signed a treaty with the British during the reign of Governor-General The Earl of Dalhousie. The British agreed to liquidate all of his debts in return for ceding part of his territory to the British.

Early life

[edit]Nasir-ud-Daulah was born as Mir Farkhunda Ali Khan in Bidar, at present-day Karnataka, India, on 25 April 1794. He was the eldest son of Nizam Sikandar Jah. Nasir-ud-Daulah's mother was Fazilat-un-Nisa Begum, the favourite wife of his father.[2][3][4] The Nizams were the erstwhile ruler of Hyderabad, the largest princely state of British India.[5]

Reign

[edit]Nasir-ud-Daulah's father Nizam Sikandar Jah died on 21 May 1829.[6] On 24 May, he ascended to the throne of Hyderabad.[2] He inherited a financially troubled state because of the irregularities of the assistant revenue minister Maharaja Chandu Lal.[7]

Upon ascending the throne, possibly on the advice of Maharaja Chandu Lal, Nasir-ud-Daulah asked Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General of India, to have Resident of Hyderabad Sir Charles Metcalfe stop interfering in matters of civil interest. The governor-general responded affirmatively and the European superintendents of civil departments were removed.[8] Throughout his reign, Bentinck followed a policy of non-intervention in the affairs of the state.[9]

Because of the state's financial difficulties, Nasir-ud-Daulah found it difficult to pay his army. The state was becoming more and more indebted to the British.[10] He mortgaged parts of his kingdom to the Arabs and the Rohillas. Smaller jagirdars (feudal landholders) also mortgaged their estates and as a result, these moneylenders controlled significant parts of the kingdom, including extensive parts of Bhir and Osmanabad districts. This made the zamindars (aristocrats) and the large jagirdars more arrogant. In Hingoli district, the Resident was forced to send troops to put down a rebellion.[11]

According to contemporaneous records, highway robbery, looting, murders and land-grabbing increased during Nasir-ud-Daulah's reign, and bribery and corruption became commonplace. The zamindars exploited the labourers.[11] Fathulla Khan, a minister of the Nizam, said these activities occurred because of the withdrawal of British officers.[12]

In 1835, the Court of Directors of the East India Company revolted and wrote to the British government that there was a breakdown of law and order in the state of Hyderabad and that they could not ignore the misrule. In response, Nasir-ud-Daulah appointed some government workers as confidential servants to various districts of the state to monitor the activities of revenue officers, to suppress any oppression and to administer justice. The servants, however, were illiterate mansabdars (military officers) of low rank, and this system failed. These servants instead became agents of the taluqdars (landed gentry), who misused them to extort money from private individuals.[9][13] Four years later, the Court of Directors wrote a similar letter.[14]

Nasir-ud-Daulah's younger brother, Prince Mubarez-ud-Daulah was inspired by the Wahhabi movement in India and had become fiercely opposed to the continued presence of the East India Company on the Indian subcontinent, allegedly formulating plans to overthrown both them and the Nizam. He struck a deal with Rasool Khan, the Nawab of Kurnool. With the help of his agents, the Resident of Hyderabad James Stuart Fraser intercepted their plans, then accused Mubarez-ud-Daulah of planning a conspiracy against Nasir-ud-Daulah. On 15 June 1839, Nasir-ud-Daulah ordered an attack on the palace of Mubarez-ud-Daulah, so that Mubarez-ud-Daulah could be arrested and held at Golconda Fort. Mubarez was successfully imprisoned, he remained so until his death in 1854.[15][16]

Under the guidance of Prime Minister Siraj-ul-Mulk (until his death in 1853) and the next Prime Minister Salar Jung I, Nasir-ud-Daulah established a modern revenue administration system.[7][17] The kingdom was divided into 16 districts, each of which was administered by a taluqdar who was responsible for its judicial and civil administration.[7] In 1846, Nasir-ud-Daulah founded the Hyderabad Medical School, which is now known as Osmania Medical College. He was interested in recruiting both men and women for the medical field.[18]

By 31 December 1850, Nasir-ud-Daulah's debts to the British had reached ₹7 million (equivalent to ₹5.0 billion or US$59 million in 2023). By mid-1852, he found it difficult to pay his own officers.[19] In 1853, he signed a treaty with the British government, during the rule of Governor-General The Earl of Dalhousie. According to this treaty, the British agreed to liquidate his debts in return for the Nizam ceding the Berar Province to the British.[20][21] In return, the British paid the Nizam's officers.[20]

Death

[edit]

On 16 May 1857, Nasir-ud-Daulah died. He was buried at the Makkah Masjid mosque.[22][23] He was succeeded by his son Afzal-ud-Daulah as the eight Nizam of Hyderabad.[24]

Personal life

[edit]Nasir-ud-Daulah had two nikkah wives. His first wife was Dilawar-un-Nisa Begum, the daughter of an unranked officer in his court. His second wife was the daughter of an officer of a lower rank who worked at his palace. He fathered two sons - one from each wife. Afzal-ud-Daulah, born in October 1827, was his son from Dilwar-un-Nisa Begum. Roshan-ud-Daulah, born March 1828, was his second son and was from his second wife.[20]

Titular Name

[edit]Upon ascending the throne, Nasir-ud-Daulah took the following titular name: Asaf Jah, Muzaffar-ul-Mumamlik, Nizam-ul-Mulk, Nizam-ul-Daulah, Mir Farkhunda Ali Khan Bahadur, Fateh Jung, Sipah Salar, Ayn Waffadar, Rustam-i-Dauran, Arastu-i-Zaman, Fidvi-i-Senliena, Iqtidar-i-Kishwarsitan, Muhammad Akbar Shah, Padshah-i-Ghazi. In English, it translates to "Asaf Jah, (equal to Asif ibn Barkhiya the minister of King Solomon), in dignity, the conqueror of dominions, the regulator of the kingdom, the administrator of the state, Mir Farkhunda Ali Khan Bahadur, the victor in battles, the leader of armies, the faithful friend, the Rustam of age, the Aristotle of present time, the slave of King Solomon who rules the realms, Muhammad Akbar Shah, the victorious king".[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bilgrami, S.A.A. (1992). Landmarks of the Deccan: A Comprehensive Guide to the Archaeological Remains of the City and Suburbs of Hyderabad. Asian Educational Services. p. 36. ISBN 978-81-206-0543-5.

- ^ a b c Briggs 2007, p. 104.

- ^ Prema Kasturi; Chitra Madhavan (2007). South India heritage: An introduction. East West Books. p. 163. ISBN 9788188661640.

Mir Farkhunda Ali Khan (1829-1857) Mir Farkhanda Ali Khan Nusir-ud-Daulu was born in Bidar on 25th April 1794. He was the eldest son of Sikander Jah and after his father's death he succeeded him on 23rd May 1829. During the reign of his father, a number of British officers were employed in several civil services. He continued in the footsteps of his father.

- ^ Chandraiah, K. (1998). Hyderabad, 400 Glorious Years. K. Chandraiah Memorial Trust. p. 233.

The Nizam permits Chandini Begum entitled Fazilat-unnisa Begum, the mother of Mubarizuddaula to visit the Golkonda Fort

- ^ Prabash K. Dutta (3 December 2018). "Beyond Yogi-Owaisi debate: The story of Nizam and Hyderabad". India Today. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ Briggs 2007, p. 100.

- ^ a b c "A brief history of the Nizams of Hyderabad". Outlook. 5 August 2017. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Briggs 2007, pp. 96, 105, 307.

- ^ a b Briggs 2007, p. 106.

- ^ Kate 1987, p. 35.

- ^ a b Kate 1987, p. 36.

- ^ Kate 1987, p. 37.

- ^ Briggs 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Briggs 2007, p. 108.

- ^ Mallampalli 2017, p. 66.

- ^ Seshan, KSS (10 June 2017). "Mubarez-ud-Daulah's era: Of passion, rebellion and conspiracy". The Hindu. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Gribble, J. D. E. History of the Deccan: Volume Two. India: Mittal Publications. pp. 234–235.

- ^ Jovita Aranha (4 March 2019). "This Forgotten Hyderabad Woman Was The World's First Female Anaesthesiologist!". The Better India. Retrieved 2 April 2019.

- ^ Briggs 2007, p. 113.

- ^ a b c Briggs 2007, p. 114.

- ^ "Pesticide poisoning continues to claim farmers' lives in Maharashtra". The Hindu. 9 December 2017. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- ^ Sarojini Regani (1988). Nizam-British Relations, 1724–1857. Concept Publishing Company. p. 300.

- ^ "Mecca Masjid, Hyderabad". British Library. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- ^ Kate 1987, p. 38.

Further reading

[edit]- Briggs, Henry George (2007), The Nizam – His History And Relations With The British Government, vol. 1, Read Books, ISBN 9781406710946

- Kate, P. V. (1987), Marathwada Under the Nizams, 1724–1948, Mittal Publications, ISBN 9788170990178

- Mallampalli, Chandra (2017), A Muslim Conspiracy in British India?, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781107196254