Nakhchivan (city)

Nakhchivan

Naxçıvan | |

|---|---|

Landmarks of Nakhchivan, from top left: Garabaghlar Mausoleum • Khan Palace Nakhcivan Hospital • Momine Khatun City Centre • Juma Mosque Feminine Centre • Nakhcivan Mountains | |

| |

| Coordinates: 39°12′58″N 45°24′38″E / 39.21611°N 45.41056°E | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous Republic | Nakhchivan |

| Area | |

• Total | 190 km2 (70 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 873 m (2,864 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 94,500 |

| Demonym | Nakhchivanly |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (AZT) |

| Website | ih |

Nakhchivan (Azerbaijani: Naxçıvan Azerbaijani pronunciation: [nɑxtʃɯˈvɑn]) is the capital and largest city of the eponymous Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, a true exclave of Azerbaijan, located 450 km (280 mi) west of Baku. The municipality of Nakhchivan consists of the city of Nakhchivan, the settlement of Əliabad and the villages of Başbaşı, Bulqan, Haciniyyət, Qaraçuq, Qaraxanbəyli, Tumbul, Qarağalıq, and Daşduz.[2] It is spread over the foothills of Zangezur Mountains, on the right bank of the Nakhchivan River at an altitude of 873 m (2,864 ft) above sea level.

Toponymy

[edit]The city's official Azerbaijani spelling is "Nakhchivan" (Azerbaijani: Naxçıvan).[3][4] The name is transliterated from Persian as Nakhjavan (Persian: نخجوان).[5][6] The city's name is transliterated from Russian as Nakhichevan' (Russian: Нахичевань) and from Armenian as Nakhijevan (Armenian: Նախիջևան, romanized: Naxiǰewan).[7][8][9][10]

The city was first mentioned in Ptolemy's Geography as Naxuana (Ancient Greek: Ναξουὰνα, Latin: Naxuana).[11] The older form of the name is Naxčawan (Armenian: Նախճաւան).[12] According to philologist Heinrich Hübschmann, the name was originally borne by the city and later given to the surrounding region.[12] Hübschmann believed the name to be composed of Naxič or Naxuč (probably a personal name) and awan, an Armenian word (ultimately of Iranian origin) meaning "place, town".[12]

In the Armenian tradition, the name of the city is connected with the Biblical narrative of Noah's Ark and interpreted as meaning "place of the first descent" or "first resting place" (as if deriving from նախ, nax, 'first' and իջեւան, ijewan, 'abode, resting place') due to it being regarded as the site where Noah descended and settled after the landing of the Ark on nearby Mount Ararat.[13][14] It was probably under the influence of this tradition that the name changed in Armenian from the older Naxčawan to Naxijewan.[14] Although this is a folk etymology, William Whiston believed Nakhchivan/Nakhijevan to be the Apobatērion ("place of descent") mentioned by the first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in connection with Noah's Ark, which would make the tradition connecting the name with the Biblical figure Noah very old, predating Armenia's conversion to Christianity in the early fourth century.[14][15][16]

History

[edit]Classical period

[edit]In the Armenian tradition, Nakhchivan was founded by Noah after the Flood, and was the place of his death and burial.[17] According to the Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi, King Tigranes I of Armenia settled Median prisoners of war at Nakhchivan in the second century BC.[18] Nakhchivan is first mentioned in Ptolemy's Geographia as Naxuana (Greek: Ναξουὰνα).[18]

Nakhchivan was destroyed by Shahanshah Shapur II in 363 and its Armenian and Jewish population was deported to Iran.[19] Emperor Heraclius travelled through the city en route to Atropatene in 623 during the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628.[20]

Medieval period

[edit]The Arab siege of Nakhchivan in 650AD led Theodore Rshtuni to conclude a truce.[19] After the rebellion of 703AD Muhammad ibn Marwan had the rebel nobles burnt alive in churches in Nakhchivan and Goghtn in 705.[19][21] Nakhchivan temporarily came under the control of the Bagratid Kingdom of Armenia in c. 900, but was swiftly taken by Muhammad ibn Abi'l-Saj.[18] The city was the temporary refuge of Atabeg Nusrat al-Din Abu Bakr after his defeat at the Battle of Shamkor in 1195, and Nakhchivan was conquered by the Kingdom of Georgia in 1197.[22]

The city and its surroundings were ruled either directly or indirectly by Zakarid Armenia from 1201 to 1350, but more often than not they only had partial independence and often were vassals of other Empires.[23] In 1225, Nakhchivan was occupied by al-Maleka al-Jalāliya, daughter of Atabeg Muhammad Jahan Pahlavan.[18] In 1236 Nakhchivan was occupied by the Mongol Empire and later the Ilkhanate forcing Zakarid Armenia to pay taxes to the Mongol lords as well as owing them loyalty and troops.[24] Genoese merchants were known to trade in the city by 1280.[25] The city was conquered by Timur in 1401,[26] but was taken by King George VII of Georgia in 1405.[27]

Modern period

[edit]

Nakhchivan was conquered by Shahanshah Ismail I in 1503.[28] Shahanshah Abbas I of Persia reconquered Nakhchivan from the Ottoman Empire in 1603–1604.[29] Later the city served as the capital of the Nakhichevan Khanate.

Nakhchivan Khanate was annexed to the Russian Empire per the Treaty of Turkmenchay in 1828.[30] The city became the centre of the Nakhichevan uezd of the Erivan Governorate in 1849.[30] In 1896, Nakhchivan had a population of 7,433, roughly two-thirds of which were Azeri-speaking Muslims and one-third Armenian Christians.[18] According to the 1897 census, Nakhchivan had the status of a county town (Russian: у. г. / уездный город, romanized: u. g. / uyezdny gorod).[31]

After the February Revolution of 1917, a soviet was formed in Nakhchivan, but the city was under the control of the Special Transcaucasian Committee from March to November 1917, and its successor the Transcaucasian Commissariat from November 1917 to March 1918.[32] Turkey occupied Nakhchivan from June until November,[32] after which the city was occupied by British soldiers in January 1919,[33] and a military governor was appointed to administer Nakhchivan.[32]

It was decided that Nakhchivan would be granted to Armenia on 6 April 1919, and the city was annexed on 6 June 1919,[34] however, some months later the city became the center of a regional Muslim uprising and pogrom against its Armenian inhabitants.[35] Britain, France, Italy, and the US, with approval from Armenia and Azerbaijan, agreed on 25 October 1919 to appoint American Colonel Edmond D. Daily as General-Governor of Nakhchivan, elections would be held, and both Armenia and Azerbaijan would withdraw its forces from the territory.[36] However, in March 1920, Turkish forces led by Kâzım Karabekir occupied Nakhchivan.[33]

Soviet Russia took control of Nakhchivan on 28 July 1920, and the city became part of the newly formed Nakhchivan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic.[37] The Treaty of Moscow of 16 March 1921, and later the Treaty of Kars of 21 October 1921, between Soviet Union and Turkey agreed that Nakhicheva would be an autonomous territory under the protection of Azerbaijan and delimited its borders with Turkey.[38][39] In February 1923, the city formed part of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Krai within the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR), but later became the capital of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the ASSR in March 1924.[37]

When Azerbaijan declared independence from the Soviet Union, Nakhchivan remained part of the Republic of Azerbaijan. Following the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, a trilateral ceasefire was signed between Armenia, Azerbaijan and Russia. According to the agreement, Azerbaijan will gain a road access to Nakhchivan through Armenia which will be secured by Russian peacekeepers.[40]

Since 9 June 2009, the Bulqan, Qaraçuq, Qaraxanbəyli, Tumbul and Haciniyyət villages of the Babek District are included in the scope of the administrative-territorial unit of the Nakhchivan city.[41]

Ecclesiastical history

[edit]The bishop of Mardpetakan resided at Nakhchivan,[19] and the Armenian historian Tovma Artsruni records Sahak Vahevuni as bishop of Nakhchivan and Mardpetakan and brother of Apusahak Vahevuni.[42]

Geography

[edit]The city is spread over the foothills of Zangezur chain, on the right bank of the Nakhchivan River at an altitude of almost 1,000 metres (3,300 feet). The floods and soil erosion spiked because of the decreased forest cover along riverbanks.[43] As a result, reforestation projects implemented in the city to encourage tree planting.[43]

Climate

[edit]Nakhchivan has a continental semi-arid climate (Köppen BSk) with short but cold, snowy winters and long, dry, very hot summers.

| Climate data for Nakhchivan (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

6.1 (43.0) |

13.4 (56.1) |

20.4 (68.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.7 (94.5) |

29.8 (85.6) |

22.3 (72.1) |

12.8 (55.0) |

5.2 (41.4) |

20.0 (67.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.9 (30.4) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

26.5 (79.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

21.8 (71.2) |

15.0 (59.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

1.0 (33.8) |

13.3 (55.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −5.3 (22.5) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

0.2 (32.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 19 (0.7) |

18 (0.7) |

29 (1.1) |

38 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

30 (1.2) |

17 (0.7) |

8 (0.3) |

11 (0.4) |

26 (1.0) |

20 (0.8) |

15 (0.6) |

267 (10.5) |

| Average precipitation days | 5 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 55 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 82.9 | 117.3 | 188.3 | 202.6 | 254.5 | 324.0 | 364.4 | 338.7 | 302.5 | 215.6 | 148.1 | 121.1 | 2,660 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 2.7 | 4.2 | 6.1 | 6.8 | 8.2 | 10.8 | 11.8 | 10.9 | 10.1 | 7 | 4.9 | 3.9 | 7.3 |

| Source 1: NOAA (precipitation 1971–1990)[44] Meteostat[45] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Deutscher wetterdinest (Daily sunshine 1971–1990)[46] | |||||||||||||

Population

[edit]According to the State Statistics Committee of Azerbaijan, the number of population of city was 63,8 thousand in 2000.[47]

| Population | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nakhchivan town | 63,8 | 64,2 | 64,7 | 65,1 | 70,7 | 71,0 | 71,3 | 71,7 | 72,7 | 82,4 | 83,4 | 84,7 | 86,4 | 88,0 | 89,5 | 90,3 | 91,1 | 92,1 | 92,9 | 93,7 |

| Urban population | 63,8 | 64,2 | 64,7 | 65,1 | 70,7 | 71,0 | 71,3 | 71,7 | 72,7 | 73,7 | 73,8 | 75,4 | 76,8 | 78,3 | 79,5 | 80,2 | 80,9 | 81,8 | 82,6 | 83,2 |

| Rural population | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 8,7 | 9,6 | 9,3 | 9,6 | 9,7 | 10,0 | 10,1 | 10,2 | 10,3 | 10,3 | 10,5 |

Demographics

[edit]| Nationality | 1829–1832 census[citation needed] | 1897 census[48] | 1916 almanac[49] | 1926 census[50] | 1939 census[51] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Azerbaijanis[a] | 3,624 | 66.25 | 6,161 | 70.09 | 6,026 | 67.45 | 7,567 | 73.49 | 11,901 | 75.83 |

| Armenians | 1,825 | 33.36 | 2,263 | 25.75 | 2,665 | 29.83 | 1,065 | 10.34 | 2,033 | 12.95 |

| Russians | 0 | 0.00 | 216 | 2.46 | 147 | 1.65 | 1,376 | 13.36 | 1,420 | 9.05 |

| Kurds | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.00 | 6 | 0.06 | 32 | 0.20 |

| Georgians | 17 | 0.31 | 24 | 0.27 | 72 | 0.81 | 24 | 0.23 | 19 | 0.12 |

| Others | 4 | 0.07 | 124 | 1.41 | 24 | 0.27 | 258 | 2.51 | 289 | 1.84 |

| TOTAL | 5,470 | 100.00 | 8,790 | 100.00 | 8,934 | 100.00 | 10,296 | 100.00 | 15,694 | 100.00 |

Economy

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2014) |

Traditionally, Nakhchivan was home to trade industry, handicraft, shoemaking and hatmaking by Azerbaijanians. These industries have been largely replaced. The restoration enterprises and development industry, liberalization of foreign trade and the extension of the customs infrastructure, which has been largely responsible for Nakchivan's growth in the last two decades, are now major parts of Nakchivan's economy.[52]

Culture

[edit]The city has a wide range of cultural activities, amenities and museums. Heydar Aliyev Palace, which has a permanent local painting exhibition and a theatre hall for an audience of 1000 people, and a recently restored Soviet-time Opera Theatre where the Nakhchivan State Musical Drama Theatre realises theatre plays, concerts, musicals and opera.[53]

Many of the city's cultural sites were celebrated in 2018 when Nakhchivan was designated an Islamic Culture Capital.[54]

Architecture

[edit]

The city is home Momine Khatun Mausoleum, Gulustan Mausoleum, Noah's Mausoleum, Garabaghlar Mausoleum, Yusif ibn Kuseyir Mausoleum, Imamzadeh mausoleum and Mausoleum of Huseyn Javid mausoleums.[55]

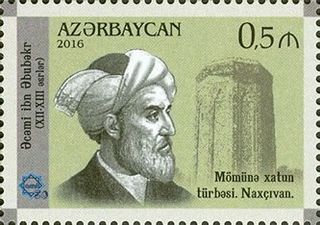

The main sight in the city is the heavily restored 12th-century Momine Khatun Mausoleum, also known as Atabek Gumbezi. Momine Khatun was the wife of Eldegizid Atabek Jahan Pahlivan, ruler of the Atabek Eldegiz emirate. The 10-sided monument is decorated with intricate geometrical motives and Kufic script, it uses turquoise glazed bricks. It shares the neighbourhood with a statue of its architect – Ajami Nakhchivani – and a bust of Heydar Aliyev. Also from the 12th century and by the same architect, is the octagonal Yusuf Ibn Kuseir tomb, known as Atababa, half abandoned near the main cemetery.

In 1993, the white marble mausoleum of Hussein Javid was built. The Azerbaijani writer died in the Gulag during Joseph Stalin's Great Purge. Both the mausoleum and his house museum are located east of the theatre. Although being a recent construction, Huseyn Javid's mausoleum is of great iconic importance, representing the ability of the exclave to live despite the Armenian embargo and becoming a symbol of Nakhchivan itself.

The mausoleums of Nakhchivan were entered for possible inclusion in the List of World Heritage Sites, UNESCO in 1998 by Gulnara Mehmandarova – president of Azerbaijan Committee of ICOMOS—International Council on Monuments and Sites.[56]

Cuisine

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Tendir lavash. (Discuss) (November 2020) |

Nakchivan’s signature cuisine includes shirin plov (sweet rice with gravy; made with mutton, hazelnuts, almonds and dried fruits), dastana, komba, tendir lavash and galin.

Lavash is made with flour, water, and salt. The thickness of the bread varies depending on how thin it was rolled out. Toasted sesame seeds and/or poppy seeds are sometimes sprinkled on before baking. It is impossible to imagine any table without bread in Azerbaijan and also in Nakhchivan. In connection with this, the assortment of bread in Nakhchivan is different; the tendir lavash as thin as paper, galin (thick), dastana, and komba (ash cake). If prepared to saj it was called lavash, "Juha salmag" – spread Juha, lavash bread on saj, and if prepared in the tandir, the "llavash yapmag" lavash bread stick. The fact is that it was necessary to stick lavash bread on the hot inner walls of the tandir. it is impossible to fight with lavash bread, as the proverb reads "Gyaldi lavash – Bitdili Savas" – "Came lavash – the end of the war". There are many people’s ideological expressions about lavash "Yavash-yavash -pendir- lavash " "Quietly (slow) – cheese lavash " or "Khamrali hash – bagryna bass", "Khamraliev" (kind of bread) push to the chest, i.e. . lavash bread – eat slowly. "Of lavash folk sandwiches are made in a roll shape – durmek. In the village where children ran out to play or school they were supplied with these sandwiches. Inside durmeks – rolls was put butter and jam, cheese, cottage cheese and butter, cheese with herbs, potatoes, boiled eggs, etc."[57]

Sacrificial monument Ashabi-Kahf

[edit]Ashabi-Kahf is a sanctuary in a natural cave which is located in the eastern part of the city of Nakhchivan, between the mountains of Ilandag and Nahajir in Azerbaijan.Since ancient times Ashabi-Kahf is considered as a sacred place.It is known not only in Nakhchivan, but also in other regions of Azerbaijan and countries of the Middle East.Each year ten thousands of people make a pilgrimage to this place.[citation needed]

Museums and galleries

[edit]The city also has many historical museums, the literature museum of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, Nakhchivan State History Museum, The Nakhchivan State Carpet Museum, and the house museums of Jamshid Nakhchivanski and Bahruz Kangarli.[58] There is also an archaeological museum found on Istiqlal street. The city has a few interesting mosques, particularly the Juma mosque, with its large dome.

Modern museums in Nakchivan include the Museum under Open Air, Heydar Aliyev Museum and the Memorial Museum (Xatıra Muzeyi), dedicated to the national strife between Armenia and Azerbaijan.[59]

Music and media

[edit]The regional channels Nakhchivan TV and now-defunct Kanal 35, and newspaper Sharg Gapisi are headquartered in the city.[60]

Sports

[edit]Araz Naxçivan one of the top futsal clubs in the European futsal arena and regularly participates in UEFA Futsal Cup.[61][62][63]

Nakhchivan had one professional football team, Araz-Naxçıvan, which competed in the top-flight of Azerbaijani football, the Azerbaijan Premier League.[64]

In 2014, the city hosted Masters Weightlifting World Cup.[65]

Festivals

[edit]Nakhchivan is known for its "Goyja" fruit, sort of a cherry-plum, and hosts a traditional Goyja festival at the Nakhchivangala Historical-Architectural Museum Complex. Products made from goyja—jam, compote (drink), pickles, dried, lavasha (bread) – are shown at the festival.[66][67]

Another festival organized annually in Nakhchivan is associated with kata (Azerbaijani: kətə) – flat pie with greens, which is made with shomu (wild spinach), mixed greens, desert candle, pumpkin, asphodel, nettle, bean or lentil in a dough wrapped in the shape of an envelope and cooked in a tandir. Kata festival is aimed to show and promote the preparation manner of various types of the kata specific to different regions of NAR. The festival is held at the Historical-Architectural Museum Complex "Nakhchivangala" in April.[68][69][70][71]

Education

[edit]There are 3 professional, 6 musical, 22 secondary schools and a military cadet school in Nakhchivan administered by the city council.[72]

Universities and colleges

[edit]Nakhchivan is home to numerous universities:

- Nakhchivan State University

- Nakhchivan Private University

- Nakhchivan Teachers Institute

Transport

[edit]Public transport

[edit]Nakhchivan's trolleybus system consisted of three lines at its height and existed until 2004.[73]

Air

[edit]

Nakhchivan International Airport is the only commercial airport serving Nakhchivan. The airport is connected by bus to the city center. There are domestic flights to Baku and international service to Russia and Turkey.

Rail

[edit]Currently, a light rail line operates from Nakhchivan southeast to Ordubad and northwest to Sharur.[74]

Notable residents

[edit]The city's notable residents include: president of Azerbaijan Heydar Aliyev, Huseyn Javid – poet and playwright, founder of the progressive romanticism in Azerbaijani literature, writer Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, opera singer Azer Zeynalov, film director Rza Tahmasib, generals Huseyn Khan Nakhchivanski and Jamshid Nakhchivanski, artist Bahruz Kangarli and architect Ajami Nakhchivani.[75] Armenian actress Hasmik who was a People's Artist of the Armenian SSR (1935), Hero of Labour (1936) and received an Order of the Red Banner of Labour (1945).

-

Heydar Aliyev, was the longest serving political leader in Azerbaijan.

-

Huseyn Javid, was the founder of the progressive romanticism in Azerbaijani literature.

-

Jalil Mammadguluzadeh, was an Azerbaijani satirist and writer.

-

Abdurrahman Fatalibeyli, was a Soviet army major who defected to the German forces during World War II.

-

Khetcho, Armenian activist, combatant and one of key supporter of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution

-

Memar Ajami, the founder of the Nakhchivan school of architecture

-

Bahruz Kangarli, the founder of realistic easel painting of Azerbaijan.

-

Rza Tahmasib, film director and actor.

-

Huseyn Khan Nakhchivanski, was the only Muslim to serve as General-Adjutant of the Russian Emperor.

-

Nazli Najafova, pioneering educator of women and girls.

-

Ali M. Hasanov, served as the National Adviser to the President of Azerbaijan.

International relations

[edit]Twin towns

[edit]Nakhchivan is twinned with various cities.

Gallery

[edit]-

Nakhchivan city

-

Face Pattern of the Momine Khatun Mausoleum

-

Huseyn Javid Home-Museum at Nakhchivan (general view)

-

The aerial view of the city in 2006

-

Monument for the Azerbaijani language

-

Old Mosque (17-18 Centuries)

-

View from Tabriz Hotel

-

Palace of Nakhchivan Khans is historical and architectural monument of the 18th century located in Nakhchivan.

See also

[edit]- Nakhchivan Khanate - Turkic Khanate which ruled over the region in 18th century

- Thamanin in southeast Turkey

- Battle of Nakhicevan

Notes

[edit]- ^ Mentioned as "Tatars" in the 1897 census, mentioned as "Shia Muslims" in the 1916 almanac, and as "Turks" or "Turko-Tatars" in the 1926 census. In the 1939 census, they are referred to as "Azerbaijanis".

References

[edit]- ^ "Population of Azerbaijan". stat.gov.az. State Statistics Committee. Retrieved 22 February 2021.

- ^ "Belediyye Informasiya Sistemi" (in Azerbaijani). Archived from the original on 24 September 2008.

- ^ "NAXÇIVAN ŞƏHƏRİNDƏKİ HEYDƏR ƏLİYEV MƏDƏNİYYƏT VƏ İSTİRAHƏT PARKINDA YENİDƏNQURMA İŞLƏRİ APARILMIŞDIR". Azerbaijan State News Agency (in Azerbaijani). 1 May 2009. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Ilham Aliyev attended ceremony to inaugurate Nakhchivan city reservoir and water purification plant complex". President.az. Presidential Administration of Azerbaijan. 7 April 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "سی کتابی که مردم جمهوری خودمختار نخجوان 'باید' بخوانند". BBC Persian Service (in Persian). 1 September 2017. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Khatina oglu, Dalga (27 February 2020). "خیز آذربایجان برای رهاندن نخجوان از وابستگی به ایران". Deutsche Welle (in Persian). Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Hakobyan, Tatul (17 March 2020). "Նախիջևանի կորուստը. մի քանի պատմական իրողություններ" [The loss of Nakhijevan: some historical facts]. CivilNet (in Armenian). Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ Babayan, Aza (15 December 2020). "Ադրբեջանն ու Թուրքիան վաղը Իգդիր-Նախիջևան գազատարի վերաբերյալ հուշագիր կստորագրեն" [Azerbaijan and Turkey will sign a memorandum on the Igdir-Nakhijevan gas pipeline tomorrow]. Azatutyun (in Armenian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Турецкие военные прибыли в Нахичевань для учений" [Turkish military arrived in Nakhichevan for exercises]. REGNUM (in Russian). 27 July 2020. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Зариф: "Есть реальная перспектива соединения железных дорог Армении и Ирана через Нахичевань"" [Zarif: "There is a real prospect of connecting the railways of Armenia and Iran through Nakhichevan"]. Эхо Кавказа (in Russian). Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ (in Russian) "Nakhichevan" in the Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary, St. Petersburg, Russia: 1890–1907.

- ^ a b c Hiwbshman, H. (1907). Hin Hayotsʻ Teghwoy Anunnerě [Ancient Armenian Place Names] (in Armenian). Translated by Pilējikchean, H. B. Vienna: Mkhitʻarean Tparan. pp. 222–223, 385.

- ^ Hakobyan, T. Kh.; Melik-Bakhshyan, St. T.; Barseghyan, H. Kh. (1991). "Nakhijevan". Hayastani ev harakitsʻ shrjanneri teghanunneri baṛaran [Dictionary of toponymy of Armenia and adjacent territories] (in Armenian). Vol. 3. Yerevan State University. pp. 951–953.

- ^ a b c Hewsen, Robert H. (1992). The Geography of Ananias of Širak (Ašxarhacʻoycʻ): The Long and the Short Recensions. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. p. 189. ISBN 3-88226-485-3.

- ^ "Chapter 3". Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ Noah's Ark: Its Final Berth Archived March 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine by Bill Crouse

- ^ Lanser 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Bosworth (2013)

- ^ a b c d Lint (2018), p. 1055

- ^ Chaumont (1986), pp. 418–438

- ^ Blankinship (1994), p. 107

- ^ Rayfield (2013), pp. 112–113

- ^ Grekov, Boris, ed. (1953). Очерки истории СССР. Период феодализма IX-XV вв.: В 2 ч. [Essays on the history of the USSR. The period of feudalism IX-XV centuries: In 2 volumes]. Moscow: Academy of Sciences of the Soviet Union. OCLC 8470090.

…the political power of the Zakarids was formed and strengthened, heading the restored Armenian statehood in indigenous Armenia. The territory subject to the Zakarids was an Armenian state, vassal to the then reigning house of the Georgian Bagratids; The Zakharid government had the right to court and collect taxes. The main responsibility of the Armenian government to the Georgian government was to provide it with military militia during the war.

- ^ Hodous, Florence (2018). "Inner Asia 1100s-1405: The Making of Chinggisid Eurasia". In Fairey, Jack; Farell, Brian (eds.). Empire in Asia: A New Global History: From Chinggisid to Qing. Vol. 1. London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 20. ISBN 9781472591234.

Vassal states such as the Uyghur kingdom of Qocho (until 1335), Zakarid Armenia, Cilicia, Georgia, and Korea similarly owed the empire taxes, troops, and loyalty, but were otherwise left to govern themselves.

- ^ Bernardini (2000), pp. 422–426

- ^ Rayfield (2013), p. 150

- ^ Rayfield (2013), p. 152

- ^ Rayfield (2013), p. 164

- ^ Herzig & Floor (2015), p. 5

- ^ a b Hille (2010), p. 66

- ^ Troinitsky, N. A. (1905). Населенные места Российской империи в 500 и более жителей с указанием всего наличного в них населения и числа жителей преобладающих вероисповеданий, по данным первой всеобщей переписи населения 1897 г. [Populated areas of the Russian Empire with 500 or more inhabitants, indicating the total population in them and the number of inhabitants of the predominant religions, according to the first general population census of 1897.] (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Tipografiya Obshchestvennaya polza. p. 54. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Hille (2010), p. 170

- ^ a b Hille (2010), p. 173

- ^ Hille (2010), p. 171

- ^ Karapetyan, Bakour. THE ROOTS OF KARABAGH PROBLEM. p. 119. Archived from the original on 3 August 2022.

Turkey instigated a Muslim revolt against the Republic of Armenia in Nakhichevan. The Armenian troops and refugees were forced to leave the region.

- ^ Hille (2010), pp. 171–172

- ^ a b Hille (2010), p. 172

- ^ Hille (2010), p. 159

- ^ Hille (2010), p. 191

- ^ Dmitry Kuznets (12 November 2020). "Another map redrawn in blood Six consequences of the six-week war for Nagorno-Karabakh". Meduza. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- ^ "Milli Məclis". www.meclis.gov.az. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ Thomas et al. (2010), p. 103

- ^ a b Hay, Mark. "How Environmentalism Can Foster Nation-Building". magazine.good.is. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Naxcivan Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Nakhchivan Climate : Temperature 1991-2020". Meteostat. Retrieved 23 December 2024.

- ^ Klimatafel von Nachitschewan (Naxcivan) / Aserbaidschan (PDF) (in German), Deutscher Wetterdinest, retrieved 23 July 2023

- ^ "Political division, population size and structure: Population by towns and regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan". Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ Демоскоп Weekly (еженедельная демографическая газета. Электронная версия): Первая всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Распределение населения по родному языку и уездам Российской Империи кроме губерний Европейской России-Нахичеванский уезд – г. Нахичевань Archived 4 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine-Источник: Первая Всеобщая перепись населения Российской Империи 1897 г. Таблица XIII. Распределение населения по родному языку. (Губернские итоги). Т.Т.51–89. С.-Петербург: 1903–1905

- ^ Кавказский календарь на 1917 год [Caucasian calendar for 1917] (in Russian) (72nd ed.). Tiflis: Tipografiya kantselyarii Ye.I.V. na Kavkaze, kazenny dom. 1917. pp. 214–221. Archived from the original on 4 November 2021.

- ^ "Нахичеванская ССР 1926". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ "население азербайджана". www.ethno-kavkaz.narod.ru. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ "NAXÇIVAN MUXTAR RESPUBLİKASI – rəsmi portal". nakhchivan.az. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ "Ilham Aliyev attended a ceremony to commemorate the 90th anniversary of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic". en.president.az. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Nakhchivan to be capital of Islamic Culture in 2018". en.apa.az. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "The mausoleum of Nakhchivan". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "The mausoleum of Nakhchivan (#)". unesco.org.

- ^ "NAXÇIVAN MUXTAR RESPUBLİKASI – rəsmi portal". nakhchivan.az.

- ^ "NAXÇIVAN MUXTAR RESPUBLİKASI – rəsmi portal". nakhchivan.az. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Peart, Ian. "Land of Legend – Nakhchivan". www.visions.az. Archived from the original on 13 November 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Radio-TV yayımı" (in Azerbaijani). Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ Футзальный клуб «Араз» определился с соперниками по элитному раунду Кубка чемпионов Archived 7 July 2012 at archive.today (in Russian)

- ^ "Happy Friday night for Benfica, Puntar and Araz". uefa.com. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ "Club's uefa.com profile". uefa.com. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ В Нахчыване появится футбольный клуб Араз. Azerifootball.com (in Russian). Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ^ "Masters World Cup 2014". nakhchivan2014.com. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Delicious goyja of Nakhchivan". turizm.nakhchivan.az. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "The traditional GOYJA FESTIVAL will be held in Nakhchivan". turizm.nakhchivan.az. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 28 June 2019.

- ^ "Cuisine of Nakhchivan – Kata". Naxçıvan TV (in Azerbaijani). Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ ""Kata" festival finished". turizm.nakhchivan.az. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Naxçıvanda kətə festivalı keçiriləcək". State News Agency of Azerbaijan (in Azerbaijani). Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ ""Kətə" festivalı böyük maraqla qarşılanıb – serqqapisi.az". Şərq Qapısı newspaper. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ "Naxçıvan Muxtar Respublikası". nakhchivan.az. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ "15. Нахичевань (троллейбус)" [15. Nahičevan (trolleybus)]. Горэлектротранс (Electrotrans) website (in Russian). Дмитрий Зиновьев (Dmitry Zinoviev). Archived from the original on 11 January 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "NAXÇIVAN MUXTAR RESPUBLİKASI – rəsmi portal". nakhchivan.az. Archived from the original on 10 June 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ "00188" Алиев Гейдар Али Рза оглы (in Russian). Справочник по истории Коммунистической партии и Советского Союза 1898–1991. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ "Batumi – Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Batumi City Hall. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bernardini, Michele (2000). "GENOA". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Blankinship, Khalid Yahya (1994). The End of the Jihad State: The Reign of Hisham Ibn 'Abd al-Malik and the Collapse of the Umayyads. State University of New York Press.

- Bosworth, C. Edmund (2013). "NAḴJAVĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Chaumont, M. L. (1986). "ARMENIA AND IRAN ii. The pre-Islamic period". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Hille, Charlotte Mathilde Louise (2010). State Building and Conflict Resolution in the Caucasus. BRILL.

- Lanser, Richard D. (2007). An Armenian Perspective on the Search for Noah's Ark (PDF). Associates for Biblical Research.

- Lint, Theo van (2018). "Nakhchivan". The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity, ed. Oliver Nicholson. Oxford University Press.

- Rayfield, Donald (2013). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. Reaktion Books.

- Thomas, David; Mallett, Alexander; Roggema, Barbara (2010). Christian-Muslim Relations. A Bibliographical History. Volume 2 (900–1050). BRILL.

- Jamalova Nigar. Armenia’s plans on the Nakhchivan territory and the countermeasures of the Azerbaijan government (1918-1920). Journal of Azərbaycan Tarixşünaslığı / Azerbaijan Historiography. 2024/6. p.25-49

External links

[edit]- Nakhchivan Guide

- Nakhchivan Portal

- Nakhchivan (as Naxçıvan) at GEOnet Names Server

- World Gazetteer: Azerbaijan[dead link] – World-Gazetteer.com