National Gallery of Victoria

NGV International on St Kilda Road in Southbank | |

| |

| Established | 24 May 1861 |

|---|---|

| Location | Southbank, Victoria, Australia |

| Coordinates | 37°49′21″S 144°58′08″E / 37.82250°S 144.96889°E |

| Type | Art museum |

| Visitors | 3,210,000 (2017–18)[1] |

| Director | Tony Ellwood |

| Public transit access | Flinders Street station Tram routes 1, 3, 5, 6, 16, 64, 67, 72 |

| Website | ngv.vic.gov.au |

| Official name | National Gallery of Victoria |

| Type | State Registered Place |

| Criteria | a, d, e, g, h |

| Designated | August 20, 1982 |

| Reference no. | H1499[2] |

| Heritage Overlay number | HO792[2] |

The National Gallery of Victoria, popularly known as the NGV, is an art museum in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Founded in 1861, it is Australia's oldest and most visited art museum.

The NGV houses its collection across two sites: NGV International, located on St Kilda Road in the Melbourne Arts Precinct of Southbank, and the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, located nearby at Federation Square. The NGV International building, designed by Sir Roy Grounds, opened in 1968, and was redeveloped by Mario Bellini before reopening in 2003. It houses the gallery's international art collection and is on the Victorian Heritage Register. The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, designed by Lab Architecture Studio, opened in 2002 and houses the gallery's Australian art collection.

A third site, The Fox: NGV Contemporary, is planned to open in the Melbourne Arts Precinct in 2028, and will be Australia's largest contemporary art gallery.

History

[edit]19th century

[edit]

In 1850, the Port Phillip District of New South Wales was granted separation, officially becoming the colony of Victoria on 1 July 1851. In the wake of a gold rush the following month, Victoria emerged as Australia's richest colony, and Melbourne, its capital, Australia's largest and wealthiest city. With Melbourne's rapid growth came calls for the establishment of a public art gallery, and in 1859, the Government of Victoria pledged £2000 for the acquisition of plaster casts of sculpture.[3] These works were displayed in the Museum of Art, opened by Governor Sir Henry Barkly in May 1861 on the lower floor of the south wing of the public Library (now the State Library of Victoria) on Swanston Street.[4] Further money was set aside in the early 1860s for the purchase of original paintings by British and Victorian artists. These works were first displayed in December 1864 in the newly opened Picture Gallery, which remained under the curatorial administration of the Public Library until 1882.[5][6] Grand designs for a building fronting Lonsdale and Swanston streets were drawn by Nicholas Chevalier in 1860 and Frederick Grosse in 1865, featuring an enormous and elaborate library and gallery, but these visions were never realised.

On 24 May 1874, the first purpose-built gallery, known as the McArthur Gallery, opened in the McArthur room of the State Library, and the following year, the Museum of Art was renamed the National Gallery of Victoria.[4] The McArthur Gallery was only ever intended as a temporary home until the much grander vision was to be realised.[7] However such an edifice did not eventuate and the complex was instead developed incrementally over several decades.

The National Gallery of Victoria Art School, associated with the gallery, was founded in 1867 and remained the leading centre for academic art training in Australia until about 1910.[8] The School's graduates went on to become some of Australia's most significant artists. This later became the VCA (Victorian College of the Arts), which was bought by the University of Melbourne in 2007 after it went bankrupt.

In 1887, the Buvelot Gallery (later Swinburne Hall) was opened, along with the Painting School studios. In 1892, two more galleries were added: Stawell (now Cowen) and La Trobe.[4]

In 1888, the gallery purchased Lawrence Alma-Tadema's 1871 painting The Vintage Festival for £4000, its most expensive acquisition of the 19th century.

20th century

[edit]

The gallery's collection was built from both gifts of works of art and monetary donations. The most significant, the Felton Bequest, was established by the will of Alfred Felton and from 1904, has been used to purchase over 15,000 works of art.[10]

Since the Felton Bequest, the gallery had long held plans to build a permanent facility; however, it was not until 1943 that the State Government chose a site, Wirth's Park, just south of the Yarra River.[11] £3 million was put forward in February 1960 and Roy Grounds was announced as the architect.[12]

In 1959, the commission to design a new gallery was awarded to the architectural firm Grounds Romberg Boyd. In 1962, Roy Grounds split from his partners Frederick Romberg and Robin Boyd, retained the commission, and designed the gallery at 180 St Kilda Road (now known as NGV International). The new bluestone clad building was completed in December 1967[13] and Victorian premier Henry Bolte officially opened it on 20 August 1968.[14] One of the features of the building is the Leonard French stained glass ceiling, one of the world's largest pieces of suspended stained glass, which casts colourful light on the floor below.[15] The water-wall entrance is another well-known feature of the building.

In 1997, redevelopment of the building was proposed, with Mario Bellini chosen as architect and an estimated project cost of $161.9 million. The design was extensive, creating all new galleries leaving only the exterior, the central courtyard and Great Hall intact.[16] The plans included doing away with the water wall, but following public protests organised by the National Trust of Victoria, the design was altered to include a new one slightly forward of the original.[17] During the redevelopment, many works were moved to a temporary external annex known as 'NGV on Russell', at the State Library with its entrance on Russell Street.[4]

21st century

[edit]

A major fundraising drive was launched on 10 October 2000 to redevelop the ageing St Kilda Road building and although the state government committed the majority of the funds, private donations were sought in addition to federal funding. The drive achieved its aim and secured $15 million from the Ian Potter Foundation on 11 July 2000, $3 million from Loti Smorgon, $2 million from the Clemenger Foundation, and $1 million each from James Fairfax and the Pratt Foundation.[18]

NGV on Russell closed on 30 June 2002[4] to make way for the staged opening of the new St Kilda Road gallery. It was officially opened by premier Steve Bracks on 4 December 2003.[19]

The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia in Federation Square was designed by Lab Architecture Studio to house the NGV's Australian art collection. It opened in 2002. As such, the NGV's collection is now housed in two separate buildings, with Grounds' building renamed NGV International.

Locations

[edit]St Kilda Road: NGV International

[edit]NGV international is located at 180 St Kilda Rd and houses the NGV's European, Asian, Oceanic and American art collections.[20] It houses a number of permanent displays, arranged by region and chronology.[21] It also has a large ground-floor space used for temporary exhibitions, and contemporary art spaces on level 3 are also used for temporary exhibitions.[21] The building is surrounded by a moat and fountains, while the main entrance features a famous water wall, which has been used to display the art of Keith Haring and others.[22][17] At the rear of NGV International is a sculpture garden, which hosts an annual large-scale installation through the NGV Architecture Commission.[23]

Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia

[edit]

NGV Australia is located in the Ian Potter Centre at Federation Square. The building houses the NGV's Australian collection, with a permanent display presenting a chronological history of Australian art and a selection of the galley's 25,000 Australian works.[24] NGV Australia has a particular focus on Indigenous Australian art, and alongside the permanent displays presents temporary exhibitions relating to Australian art and history.

The Fox: NGV Contemporary

[edit]In 2018, the State Government of Victoria announced a new contemporary art gallery would be built behind the Arts Centre and the existing NGV International building.[25] The Government spent $203 million to begin the project, including $150 million to purchase the former Carlton and United Breweries building for the new gallery.[25] The new building is part of a major new $1.7 billion redevelopment of the surrounding Melbourne Arts Precinct which is planned to include 18,000 square metres of new public space, new space for contemporary art and design exhibitions, and a new home for the Australian Performing Arts Gallery.[26][27] The Ian Potter Foundation pledged $20 million for the new building.[28] The masterplan for the precinct was approved in 2022.[27] The public space is being designed by architecture firms HASSELL and SO-IL with a new elevated garden connecting Hamer Hall and Southbank Boulevard.[29][30]

The winner of the design competition for the NGV Contemporary was announced in March 2022 as Angelo Candalepas and Associates.[31] In April it was announced that billionaires Paula and Lindsay Fox had donated $100 million to the NGV Contemporary project in the largest ever donation to an Australian art museum, and that the gallery would be named The Fox: NGV Contemporary.[28] The new gallery will have 13,000 square metres of exhibition space and is planned to open in 2028.[32][33] It will be Australia's largest contemporary gallery.[34]

Collection

[edit]Asian art

[edit]

The NGV's Asian art collection began in 1862, one year after the gallery's founding, when Frederick Dalgety donated two Chinese plates. The Asian collection has since grown to include significant works from across the continent.

Australian art

[edit]The NGV's Australian art collection encompasses Indigenous (Australian Aboriginal) art and artefacts, Australian colonial art, Australian Impressionist art, 20th century, modern and contemporary art. The first curator of Australian Art was Brian Finemore, from 1960 until his death in 1975.[35]

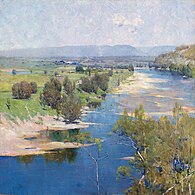

The 1880s saw the birth and development of the Heidelberg School (also known as Australian Impressionism) in the outer suburbs of Melbourne, and the NGV was well-placed to acquire some of the movement's key artworks, including Tom Roberts' Shearing the Rams (1890), Arthur Streeton's The purple noon's transparent might (1896), and Frederick McCubbin's The Pioneer (1904).[36]

The Australian collection includes works by Del Kathryn Barton, Charles Blackman, Clarice Beckett, Arthur Boyd, John Brack, Angela Brennan, Rupert Bunny, Louis Buvelot, Ethel Carrick, Nicholas Chevalier, Charles Conder, Olive Cotton, Grace Crowley David Davies, Destiny Deacon, William Dobell, Julie Dowling, Russell Drysdale, E. Phillips Fox, Rosalie Gascoigne, John Glover, Eugene von Guerard, Fiona Hall, Louise Hearman, Joy Hester, Hans Heysen, Emily Kame Kngwarreye, George W. Lambert, Sydney Long, John Longstaff, Frederick McCubbin, Helen Maudsley, Tracey Moffatt, Jan Nelson, Hilda Rix Nicholas, Sidney Nolan, John Perceval, Patricia Piccinini, Margaret Preston, Thea Proctor, Hugh Ramsay, David Rankin, Tom Roberts, John Russell, Grace Cossington Smith, Ethel Spowers, Arthur Streeton, Clara Southern, Jane Sutherland, Violet Teague, Jenny Watson, Fred Williams and others.[37]

A large number of works were donated by Dr. Joseph Brown in 2004 which form the Joseph Brown Collection.

Selected works

-

Aboriginal shields

-

The Buffalo Ranges (1864) by Nicholas Chevalier, the first painting of an Australian subject to be acquired by the gallery

-

Tom Roberts, Shearing the Rams, 1890

-

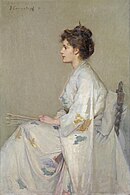

John Longstaff, Lady in Grey, 1890

-

John Russell, Rough Sea, Belle-Île, c. 1900

-

E. Phillips Fox, The Lesson, 1912

-

Clarice Beckett, Evening light, Beaumaris, c. 1925

International art

[edit]

The NGV's international art collection encompasses European and international paintings, fashion and textiles, photography, prints and drawings, Asian art, decorative arts, Mesoamerican art, Pacific art, sculpture, antiquities and global contemporary art. It has strong collections in areas as diverse as old masters, Greek vases, Egyptian artefacts and historical European ceramics, and contains the largest and most comprehensive range of artworks in Australia.[38]

The international collection includes works by Arbus, Bernini, Bonnard, Bordone, Canaletto, Cézanne, Constable, Correggio, Dalí, Degas, Delaunay, van Dyck, Emin, Gainsborough, Gentileschi, El Greco, Lange, Manet, Matisse, Memling, Modigliani, Monet, Moore, Munch, Picasso, Pissarro, Pittoni, Poussin, Rembrandt, Renoir, Ribera, Riley, Rothko, Rubens, Soulages, Tiepolo, Tintoretto, Titian, Turner, Uccello, Veronese and others.

One of the highlights of the NGV's international collection is Auguste Rodin's first cast of his iconic sculpture The Thinker, executed in 1884.[39] The NGV is also home to the only portrait of Lucrezia Borgia known to have been painted from life, dated to approximately 1515 and attributed to Dosso Dossi.[40]

Selected works

-

Paolo Uccello, St. George Slaying the Dragon, 1430

-

Correggio, Madonna and Child with infant St John the Baptist, 1514–15

-

Rembrandt, Two old men disputing, 1628

-

Thomas Gainsborough, Richard St George Mansergh-St George, 1776

-

John Everett Millais, The Rescue, 1855

-

August Friedrich Schenck, Anguish, 1878

-

Jules Bastien-Lepage, October, 1878

-

Claude Monet, Vétheuil, 1879

-

Paul Cézanne, The Uphill Road, 1881

-

Gustave Caillebotte, The plain of Gennevilliers, yellow fields, 1884

-

Camille Pissarro, Boulevard Montmartre, morning, cloudy weather, 1897

-

Pierre Bonnard, Siesta, 1900

-

Edvard Munch, Early Spring, 1905

-

Amedeo Modigliani, Portrait of the painter Manuel Humbert, 1916

-

Suzanne Valadon, Nude with drapery, 1921

-

Salvador Dalí, Mae West Lips Sofa, 1937

Photography

[edit]

In 1967, the NGV established the first curatorial department dedicated to photography in an Australian public gallery,[41] one of the first in the world. It now holds over 15,000 works. In that same year, the Gallery acquired the photography collection's first work, Surrey Hills street 1948 by David Moore[1] and in 1969 the first international work was acquired, Nude 1939 by František Drtikol[2]. The first photographer to exhibit solo at the NGV was Mark Strizic in 1968.[42][43] Jennie Boddington, a filmmaker, was appointed first full-time curator of photography in 1972, possibly only the third such appointment amongst world public institutions.[44][45]

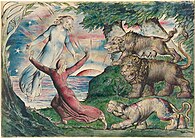

Prints and drawings

[edit]The NGV's Department of Prints and Drawings is responsible for one third of the gallery's collection. Highlights among the department's holdings include one of the world's largest collections of engravings and woodcuts by Dürer.[46] The NGV is also said to have one of the most impressive collections of works by William Blake, including 36 of the 102 watercolours he worked on up until his death in 1827 to illustrate the Divine Comedy by Dante, the largest number of works from this series held by any gallery in the world.[47][48] Rembrandt and Goya are also well-represented, and the Australian collection contains a detailed account of the history of graphic arts in Australia.[49]

The NGV no longer dedicates a space to exhibiting works from the Prints and Drawings collection, though some works on paper are rotated within the permanent collection galleries and may appear in exhibitions.[49] Works in the collection may be viewed by appointment in the department's Print Study Room.[49]

Selected works

-

Albrecht Dürer, Melencolia I, 1514

-

William Blake, Dante running from the three beasts, 1824

-

J. M. W. Turner, The Red Rigi, 1842

-

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Paolo and Francesca da Rimini, 1867

-

Ford Madox Brown, The finding of Don Juan by Haidée, 1869

-

Edvard Munch, Towards the Forest II, 1897

Controversies

[edit]As a "National Gallery"

[edit]When plans for the construction of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra became firmly established in the 1960s, Australia's state galleries removed the word "national" from their names (for example, the National Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney became the Art Gallery of New South Wales). This naming convention dated back to the 19th century when Australia's colonies were self-governing political entities and had yet to federate. Only the NGV has retained "national" in its name.[50] This has proven to be somewhat contentious, given that the NGV is technically not a national gallery, and occasionally there have been calls for it to follow the example of the other state galleries.

Withdrawal of Chloé

[edit]In May 1883, when the National Gallery of Victoria opened on a Sunday for the first time, a public debate erupted over the propriety of displaying a female nude portrait on the Sabbath. The painting in question, French artist Jules Joseph Lefebvre's Chloé (1875), had been loaned to the gallery that month, and was "cautiously displayed in a dim corner". Nonetheless, Chloé became "Melbourne's femme fatale", and after three weeks of scandal, was withdrawn and hidden from the public. It eventually found a permanent home at Melbourne's Young and Jackson Hotel, down the road from the NGV on Swanston Street.[51]

Slaughtered Cow happening

[edit]In 1975, painter and performance artist Ivan Durrant deposited a cow carcass in the NGV forecourt.[52] Durrant later stated that it was part of a performance art piece intended to shock those who might be horrified by the death of the animal while also happy to consume meat.[53] At the time, the NGV denounced the piece as a "sick and disgusting act".[54]

Picasso theft

[edit]A famous event in the gallery's history occurred in 1986 with the theft of Pablo Picasso's painting The Weeping Woman (1936). A person or group identifying themselves as the "Australian Cultural Terrorists" claimed responsibility for the theft, stating that the painting was stolen in protest against the perceived poor treatment of the arts by the state government of the time. They sought as a ransom the establishment of an art prize for young artists. The painting was found undamaged in a railway locker two weeks later and returned to the gallery.[55]

Piss Christ

[edit]During a retrospective of Andres Serrano's work at the NGV in 1997, the then Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, George Pell, sought an injunction from the Supreme Court of Victoria to restrain the gallery from publicly displaying Piss Christ, which was not granted. Some days later, one patron attempted to remove the work from the gallery wall, and two teenagers later attacked it with a hammer.[56] Gallery officials reported receiving death threats in response to Piss Christ.[57] NGV Director Timothy Potts cancelled the show, allegedly out of concern for a Rembrandt exhibition that was also on display at the time.[56] Supporters argued that the controversy over Piss Christ is an issue of artistic freedom and freedom of speech.[57]

Special exhibitions

[edit]An exhibition known as The Field opened the gallery's new premises on St Kilda Road in 1968.[58] Reflecting the influence of abstract art, particularly New York-inspired hard edge and color field painting, it featured 74 works by forty (mostly emerging young) Australian painters and sculptors. Described as a radical departure from the gallery's more traditional program, it signified more broadly a growing internationalisation of the Australian art world.[59][60] The NGV held an exhibition titled "The Field Revisited" in 2018 to mark its 50th anniversary.[61]

Melbourne Winter Masterpieces

[edit]The NGV has held several large exhibitions known as Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibitions, starting with Impressionists: Masterpieces from the Musee d'Orsay in 2004.

| Year | Duration | Exhibition title | Attendance[62] | Notable works and information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 17 June – 26 September | Impressionists: Masterpieces from the Musée d'Orsay | 371,000 | An additional exhibition of Caravaggio paintings was also held in 2004 |

| 2005 | 24 June – 2 October | Dutch Masters from the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam | 219,000 | Vermeer's painting Woman Reading a Letter was exhibited, the first time a Vermeer painting had been exhibited in Australia |

| 2006 | 30 June – 8 October | Picasso: Love and War 1935–1945 | 224,000 | Over 300 Picasso drawings and paintings from 1935 to 1945, curated by Anne Baldassari, Director of the Musée Picasso, Paris[63] |

| 2007 | 30 June – 7 October | Guggenheim Collection 1940s to now | 180,000 | More than 85 works by 68 artists, mainly from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, but also from other Guggenheim Museums in Venice, Bilbao, and Berlin. The exhibition did not travel to any other city[64][65] |

| 2008 | 28 June – 5 October | Art Deco 1910—1939 | 241,000 | Organised by the Victoria and Albert Museum, London[66] |

| 2009 | 13 June – 4 October | Salvador Dalí Liquid Desire | 333,000 | |

| 2010 | 19 June – 10 October | European Masters: Städel Museum, 19th–20th Century | 200,000 | |

| 2011 | 13 June – 4 October | Vienna Art and Design | 172,000 | |

| 2012 | 2 June – 7 October | Napoleon: Revolution to Empire | 189,000 | |

| 2013 | 10 May – 8 September | Monet's Garden: The Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris | 342,000 | |

| 2014 | 16 May – 31 August | Italian Masterpieces from Spain's Royal Court, Museo del Prado | 153,000 | |

| 2015 | 31 July – 8 November | Masterpieces from the Hermitage: The Legacy of Catherine the Great | 172,000 | Exhibition featured pieces by Rembrandt, Rubens, Velazquez, Van Dyck and others |

| 2016 | 24 June – 18 September | Degas: A New Vision | 197,500 | |

| 2017 | 28 April – 12 July | Van Gogh and the Seasons | 462,262 | Exhibition recorded a total attendance figure of 462,262, making it the most popular ticketed art exhibition ever presented in Victoria,[67] and the most successful ticketed exhibition in the gallery's 156-year history.[68][69] The exhibition is credited for generating almost $56 million for the Victorian economy.[70] |

| 2018 | 9 June – 7 October | MoMA: 130 Years of Modern and Contemporary Art | 404,034 | Exhibition in partnership with the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Includes over 200 key works arranged into eight chronological and thematic sections.

The exhibition concluded with a total attendance figure, of 404,034, making it the NGV's second most attended ticketed exhibition on record.[71] |

| 2019 | 24 May – 13 October | Terracotta Warriors and Cai Guo-Qiang | 377,105 | The exhibition included a large-scale presentation of China's first emperor's Terracotta Warriors presented alongside an exhibition of new, commissioned works by Chinese contemporary artist Cai Guo-Qiang.[72][73][74] The exhibition include 150 historical Chinese artefacts, eight terracotta warriors, two full-sized horses and two replica bronze chariots of Zhou, Qin, Han dynasties, which were lent by Shaanxi History Museum in Xi'an and many other Chinese institutes.[72] |

| 2020 | N/A | N/A | The 2020 Winter Masterpieces exhibition was to be a presentation of works by French post-impressionist painter Pierre Bonnard. Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, this exhibition was delayed until 2023.[75] | |

| 2021 | 4 June – 3 October | French Impressionism: From the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston | The exhibition included 100 impression works from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, including 79 works that had never been exhibited in Australia.[76] Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic, this exhibition closed weeks after opening and could not reopen.[77] | |

| 2022 | 10 June – 9 October | The Picasso Century | The 2022 Winter Masterpiece exhibition is a career retrospective of Pablo Picasso, developed for the NGV by the Centre Pompidou and the Musée Picasso Paris.[78] It features 70 works by Picasso alongside 100 works by his contemporaries and influences, drawn from French collections.[78][79] The exhibition contributed $91 million to the Victorian economy, making it the exhibition with the highest economic impact in the history of the Melbourne Winter Masterpieces series.[80] | |

| 2023 | 6 June – 8 October | Pierre Bonnard: Designed by India Mahdavi | ||

| 2024 | 14 June – 6 October | Pharaoh[81] |

Melbourne Now

[edit]In 2013 the NGV launched "Melbourne Now", an exhibition which celebrated the latest art, architecture, design, performance and cultural practice to reflect the complex cultural landscape of creative Melbourne. "Melbourne Now" ran from 22 November 2013 – 23 March 2014 and attracted record attendances of 753,071.[82]

A decade after the original exhibition, a second edition of Melbourne Now ran from 24 March 2023 to 20 August 2023 at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia. The exhibition, which celebrated home-grown art and design from over 200 Victorian-based emerging and established artists, designers, studios and firms, drew 433,575 attendees, which made the exhibition one of the most popular exhibitions at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia.[83]

NGV Triennial

[edit]Following the success of "Melbourne Now", in March 2014 the NGV announced a major new initiative, the NGV Triennial. Beginning in the Summer of 2017, it is intended as a large-scale celebration of the best of contemporary international art and design.[84] The inaugural Triennial ran from 15 December 2017 to 15 April 2018, and drew almost 1.3 million visitors during its run, making it the most attended exhibition in the gallery's history until then.[85][86][87]

The 2020–21 NGV Triennial opened on 19 December 2020 and closed on 18 April 2021. The exhibition, which attracted more than 548,000 visitors during its run,[88] showcased works by more than 100 artists, designers and collectives from 30 countries, with 34 newly commissioned works from a mixture of both Australian and international artists.[89]

The 2023–24 NGV Triennial, running from 3 December 2023 until 7 April 2024, featured over 75 projects by 100 artists, designers and collectives from over 30 countries.[90] The exhibition attracted 1,063,675 visitors during its run, making it one of the most popular exhibitions in the NGV’s history.[91]

Publications

[edit]The Art Journal of the National Gallery of Victoria, usually referred to as the Art Journal, was first published as The Quarterly Bulletin of the National Gallery of Victoria in 1945, changing its name and frequency in 1959 to the Annual Bulletin of the National Gallery of Victoria,[92] then to the Art Bulletin of Victoria in 1967–68 (edition 9)[93] (abbreviated to ABV, edition 42). For edition 50 in 2011, in its 50th year of publication and 150th anniversary of the gallery,[94] the name was changed to its present name.[95]

The NGV also publishes a bi-monthly magazine, NGV Magazine.[96]

Directors of the NGV

[edit]Directors of the NGV since its inception:[97]

- G. F. Folingsby, 1882–1891

- Lindsay Bernard Hall, 1892–1935[98]

- William Beckwith McInnes, (acting) 1935–1936

- P. M. Carew-Smyth, (acting) 1937

- J. S. Macdonald, 1936–1941

- Sir Ernest Daryl Lindsay, 1942–1955

- Eric Westbrook, 1956–1973

- Gordon Thomson, 1973–1974

- Eric Rowlison, 1975–1980

- Patrick McCaughey, 1981–1987

- T. L. Rodney Wilson, 1988

- James Mollison, AO, 1989–1995

- Timothy Potts, 1995–1998

- Dr Gerard Vaughan, 1999–2012

- Tony Ellwood, 2012–present[99]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ National Gallery of Victoria (2018). "NGV Annual Report 2017/18" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2019.

- ^ a b "National Gallery of Victoria". Victorian Heritage Database. Government of Victoria. Archived from the original on 23 September 2023. Retrieved 27 November 2023.

- ^ Mansfield, Elizabeth. Art History and Its Institutions: Foundations of a Discipline. Psychology Press, 2002. p. 105

- ^ a b c d e [The History of the State Library of Victoria http://guides.slv.vic.gov.au/slvhistory/museumgallerypro Archived 31 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine]

- ^ Lane, Terence. Nineteenth-century Australian Art in the National Gallery of Victoria. National Gallery of Victoria, 2003. pp. 13–14.

- ^ McCulloch, Alan. The Encyclopedia of Australian Art. University of Hawaii Press, 1994. p. 815

- ^ State Library of Victoria Complex. 328 Swanston Street, Melbourne Conservation Management Plan. Lovell Chen

- ^ McCulloch, Alan; Susan McCulloch (1994). The Encyclopedia of Australian Art. Allen & Unwin. p. 864 (Appendix 8). ISBN 1-86373-315-9.

- ^ Shmith, Michael. "Raising the roof with a glass ceiling" Archived 24 June 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Age. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ^ "NGV Media | Welcome to NGV Media". ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 15 August 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ National Gallery of Victoria – Victorian Heritage Register

- ^ " 'Democratic' Art Gallery Planned". The Canberra Times. 27 February 1960

- ^ Green, Louise McO. "NGV Women's Association History". National Gallery of Victoria. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- ^ The Canberra Times. Wed 21 Aug 1968. pg 3

- ^ Stephens, Andrew (17 August 2018). "Is this Melbourne's favourite ceiling? 50 years on, we're still looking up at NGV". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ "The National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) Redevelopment". Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Waterwall at Melbourne's NGV". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- ^ National Gallery of Victoria, Annual Report 2000–2001 Archived 30 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ National Gallery of Victoria Annual Report 2003–2004 Archived 30 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NGV International – What's On". whatson.melbourne.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 15 February 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b NGV (March 2022). "Map of NGV International and Australia" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 March 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Percival, Lindy (20 November 2019). "Keith Haring's doomed mural returns to Melbourne's iconic water wall". The Age. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Ponder this: 2021 NGV Architecture Commission opens". ArchitectureAU. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia – What's On". whatson.melbourne.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b Andie Noonan (3 June 2018). "Art lovers rejoice — Melbourne to get new contemporary art gallery". ABC News. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Hinchliffe, Joe (2 June 2018). "'Game-changer': Melbourne to build nation's largest contemporary art gallery". The Age. Archived from the original on 23 November 2020. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ a b Miller, Nick (10 March 2022). "$1.7 billion Southbank arts plan approved despite 'urban blight' warning". The Age. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ a b "Lindsay and Paula Fox make record $100 million donation to Melbourne gallery". ABC News. 19 April 2022. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "Team appointed to design Melbourne Arts Precinct public realm | Arts Centre Melbourne". www.artscentremelbourne.com.au. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ "'Dramatic, diverse' planting design for proposed Melbourne Arts Precinct public spaces". Landscape Australia. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Kolovos, Benita (15 March 2022). "'Gamechanger': design unveiled for National Gallery of Victoria's contemporary art space". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ NGV (March 2022). "About The Fox: NGV Contemporary". Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 25 May 2022.

- ^ Juanola, Marta (15 March 2022). "'A magnet for tourists': State government unveils design of NGV Contemporary". The Age. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ Dan Andrews [@DanielAndrewsMP] (14 March 2022). "Say hello to NGV Contemporary" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022 – via Twitter.[better source needed]

- ^ Maureen Gilchrist, "High regard for Brian Finemore", The Age, 27 October 1975, p. 2

- ^ Galbally, Ann. The Collections of the National Gallery of Victoria. Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 9780195545913, p. 36.

- ^ "Collection | NGV". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 21 April 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2021.

- ^ "Collection Online > collections > Collection Areas". ngv.vic.gov.au. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 August 2013. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ Blanchetière, François; Thurrowgood, David (2013). "Two Insights Into Augustus Rodin's The Thinker". Art Journal. National Gallery of Victoria. 52.

- ^ "NGV Solves Mystery of Renaissance Portrait" Archived 17 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine (26 November 2008), NGV. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Although the Art Gallery of South Australia began collecting photographs as fine art in 1922, it houses them with 'Australian Prints, Drawings and Photographs'(see: http://www.artgallery.sa.gov.au/agsa/home/Collection/australlian_prints_drawings_and_photographs.html Archived 2 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine). Other Photography collections in public galleries are: The Art Gallery of New South Wales, est.1975 (see: http://www.artgallery.nsw.gov.au/collection/photography/ Archived 27 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine); Queensland Art Gallery| Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA) started their collection in 1987 where works are housed as art of the Contemporary Australian Art collection

- ^ Mark Strizic: A Journey in Photography information National Portrait Gallery Travelling Exhibitions site http://www.portrait.gov.au/site/exhibition_subsite_strizic4.php Archived 28 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Coslovich, Gabriella (19 October 2011). "Times a-changin' caught on camera". The Age. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Ely, Deborah. History of Photography, 1 June 1999, Vol. 23(2), pp. 118–122

- ^ Cox, Leonard B. The National Gallery of Victoria, 1861–1968: The Search for a Collection. Melbourne: The National Gallery of Victoria; Brown Prior Anderson Pty Ltd, 1971

- ^ Zdanowicz, Irena. Albrecht Dürer in the Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria. National Gallery of Victoria, 1994. ISBN 9780724101696.

- ^ "NGV to showcase its William Blake collection" Archived 8 April 2018 at the Wayback Machine (25 March 2014), Arts Review. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Harford, Sonia (4 April 2014). "The resurrection of William Blake's illustrations on Dante's Divine Comedy". The Age. Archived from the original on 25 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ a b c "Prints & Drawings | NGV". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 4 March 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Knell, Simon. National Galleries. Routledge, 2016. ISBN 9781317432425, p. 104.

- ^ Bell, Katrina. "Evanescence of an Artist's Model Archived 30 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine". Index Journal. Issue 1

- ^ Rule, Dan (14 February 2011). "From unholy cows to horses for courses". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 April 2011. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ Northover, Kylie (20 November 2020). "I want people to run out of the f—king gallery: Ivan Durrant". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Ivan Durrant, Barrier Draw" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 January 2021.

- ^ Justin Murphy; Susan Cram (19 September 2004). "Stolen Picasso". Rewind (ABC TV). Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on 30 July 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2010.

- ^ a b Casey, Damien (June 2000). "Sacrifice, Piss Christ, and liberal excess". Law Text Culture. Archived from the original (Reprint) on 9 June 2010. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ a b Roth, Martin (1999). "Chapter 10: When Blasphemy Came to Town". Living Water to Light the Journey. MartinRothOnline.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ The Field : Exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, August 21 – September 28, 1968, National Gallery of Victoria, 1968, archived from the original on 5 December 2020, retrieved 30 September 2020

- ^ Patrick McCaughey, "Changing situation of our art", The Age, 28 August 1968, p. 6.

- ^ Patrick McCaughey, "The significance of The Field", in Art & Australia, December 1968, p. 235.

- ^ "NGV to Restage 1968's Groundbreaking Exhibition 'The Field'" Archived 4 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Daily Review (14 March 2018). Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- ^ Creative Victoria. "Melbourne Winter Masterpieces". creative.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 8 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ^ "Arts Victoria – Melbourne Winter Masterpieces". Archived from the original on 7 January 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2009.

- ^ "Guggenheim Collection: 1940s to Now". NGV. 2007. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ "Guggenheim leaves Melbourne". Entertainment Depot, Australia. 8 October 2007. Archived from the original on 31 July 2008. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ "Art Deco". NGV. 2008. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ^ "Record-Busting Van Gogh Draws Over 110,000 Tourists To Victoria". Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- ^ Cunningham, Melissa (12 July 2017). "Starry final night for Van Gogh and the Seasons at National Gallery of Victoria". The Age. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Van Gogh works draw record crowds to NGV". 9 News. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "Melbourne Winter Masterpieces". Creative Victoria. Government of Victoria. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ "More than 400,000 visit MoMA at NGV" (PDF). National Gallery of Victoria. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- ^ a b "Terracotta Warriors & Cai Guo-Qiang | NGV". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Francis, Hannah (17 December 2018). "Terracotta warriors march towards Melbourne with a bang". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Jefferson, Dee (25 May 2019). "Beyond terracotta warriors: Artist provides antidote to simplistic, 'exoticised' idea of China". ABC News. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- ^ Dowse, Nicola. "The NGV's 2020 winter masterpiece exhibition has been postponed for three years". Time Out Melbourne. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ Dowse, Nicola. "The NGV's French Impressionism exhibition won't reopen: but you can see it online". Time Out Melbourne. Archived from the original on 14 November 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "French Impressionism at NGV Virtual Tour". Broadsheet. Archived from the original on 28 April 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ a b NGV (April 2022). "Exhibition page: The Picasso Century". Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "A World-Premiere Picasso Exhibition – With 70 Masterpieces – Is Coming to Melbourne". Broadsheet. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2022.

- ^ "Booming Major Events Calendar Boosts Victorian Jobs". Premier of Victoria. Victorian Government. Archived from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "World-Exclusive Pharaoh Exhibition To Take Over NGV". Premier of Victoria. Victorian Government. Archived from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "NGV Media". NGV. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ "Home-Grown Art A Crowd Favourite At NGV". Premier of Victoria. Victorian Government. Archived from the original on 27 November 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "NGV Media". NGV. 2014. Archived from the original on 23 April 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Neutze, Ben. "The NGV's Triennial is the gallery's most-visited exhibition ever". Time Out. Archived from the original on 11 June 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Plant, Simon. "NGV Triennial exhibition reaches record 1 million visitors". news.com.au. News Corp. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Noonan, Andie (3 June 2018). "Melbourne to build largest contemporary art gallery in Australia". ABC News. Australia. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ "'Buzz is coming back to Melbourne': Weekend foot traffic nears pre-pandemic level". The Age. 18 April 2021. Archived from the original on 19 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ "NGV Triennial to Be Part of a Summer Like No Other". Premier of Victoria. Victorian Government. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "NGV Triennial 2023: 75+ Projects by 100 Artists, Designers and Collectives from 30+ Countries". National Gallery of Victoria. Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- ^ "NGV TRIENNIAL: MORE THAN 1,063,000 VISITORS SEE BLOCKBUSTER EXHIBITION". National Gallery of Victoria. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Art Journal". NGV. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Art bulletin of Victoria, Council of the National Gallery of Victoria, 1968, ISSN 0066-7935, archived from the original on 14 November 2022, retrieved 6 December 2020

- ^ "Edition 50". NGV. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- ^ Art journal of the National Gallery of Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria. Council of Trustees, 2011, ISSN 1839-4140, archived from the original on 14 November 2022, retrieved 6 December 2020

- ^ "NGV Magazine | NGV". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 15 November 2024.

- ^ Alan McCulloch, Susan McCulloch and Emily McCulloch Childs, The New McCulloch's Encyclopedia of Australian Art (4th edition), Aus Art Editions & Miegunyah Press, 2006, p. 458.

- ^ Ann E. Galbally (1983). "Lindsay Bernard Hall (1859–1935)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 9. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943.

- ^ "Tony Ellwood, Director of the National Gallery of Victoria | NGV". www.ngv.vic.gov.au. Archived from the original on 8 May 2021. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Egyptian objects in NGV (Conorp Egypt) at the Wayback Machine (archived 17 February 2016)

- Video: Artscape – The NGV Story (Part 1), (Part 2) Archived 13 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "National Gallery of Victoria". Google Arts & Culture.

- Art museums and galleries in Melbourne

- Landmarks in Melbourne

- Buildings and structures in the City of Melbourne (LGA)

- Heritage-listed buildings in Melbourne

- Buildings and structures completed in 1968

- Modernist architecture in Australia

- Brutalist architecture in Australia

- Art museums and galleries established in 1861

- 1861 establishments in Australia

- National museums of Australia

- Collection of the National Gallery of Victoria

- Southbank, Victoria