Tympanostomy tube

| Tympanostomy tube | |

|---|---|

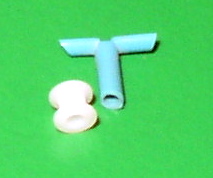

The grommet is less than 2 mm tall, smaller than a match head. | |

| Other names | Grommet, T-tube, ear tube, pressure equalization tube, vent, PE tube, myringotomy tube |

Tympanostomy tube, also known as a grommet, myringotomy tube, or pressure equalizing tube, is a small tube inserted into the eardrum via a surgical procedure called myringotomy to keep the middle ear aerated for a prolonged period of time, typically to prevent accumulation of fluid in the middle ear.[1]

The tube itself is made in a variety of designs, most often shaped like a grommet for short-term use, or with long flanges and sometimes resembling a T-shape for long-term use.[2] Materials used to manufacture the tubes are often made from fluoroplastic or silicone, which have largely replaced the use of metal tubes made from stainless steel, titanium, or gold.[2]

Medical uses

[edit]

Inserting tympanostomy tubes is one of the most common pediatric surgical procedures in the United States, with 9% of children having had tubes placed sometime in their lives.[1][3] Tympanostomy tubes are typically placed in one or both eardrums to help children suffering from recurrent acute otitis media (ear infection) or persistent otitis media with effusion (sometimes called "glue ear").[1][4][5]

Tympanostomy tubes work by improving drainage, allowing air to circulate in the middle ear, and offering a direct route for antibiotics to enter the middle ear.[2][6] Tube placement has been shown to increase hearing in children with persistent otitis media with effusion and may lead to fewer ear infections for children with frequent ear infections.[1][2] Once placed, short-term tubes are designed to stay in the eardrum for 6–15 months, whereas long-term tubes are designed to stay for 15–18 months.[2][6] Tympanostomy tubes usually fall out on their own as the eardrum heals over time; however, they can sometimes get stuck in the eardrum and require surgical assistance for removal.[2]

Guidelines state that tubes are an option in:

- Recurrent acute otitis media: three ear infections in six months or four infections in a year.[1][7]

- Chronic otitis media with persistent effusion for six months (one ear) or three months (both ears).[1][7]

- Tympanostomy tubes should only be inserted in children with persistent effusion during an active episode of effusion.[1]

- Tympanostomy tubes should not be inserted in children who have only one episode of otitis media with effusion that lasts less than three months.[1][7][8]

While tympanostomy tubes are commonly used in children, they are seldom used in adults. Options for use in adults include:

- Persistent eustachian tube dysfunction.[6]

- Fluid build-up in the middle ear due to a systemic disease.[6][clarification needed]

- Barotrauma prevention with hyperbaric oxygen treatment.[6]

Adverse effects

[edit]Otorrhea (ear discharge) is the most common complication of tympanostomy tube placement, affecting between 25–75% of children receiving this procedure.[2][6][9][10] Saline washouts and antibiotic drops at the time of surgery are effective measures to reduce rates of otorrhea, which is why antibiotic ear drops are not routinely prescribed.[1][6][9] If children experience persistent ear drainage or have new discharge two weeks following surgery, antibiotic ear drops are an effective treatment and have been shown to work better than oral antibiotics.[1][9][10] Frequent use of ear drops in children may have an ototoxic effect, which is why antibiotic ear drop use following surgery should only be recommended by a trained healthcare professional.[9]

Potential risks of tympanostomy tube placement in children include going under general anesthesia to have the procedure as well as adverse effects following tube placement.[1] Estimates of these other adverse effects from tubes being in the eardrum include:

- Persistent tympanic membrane perforation (1-6%); long-term tubes compared to short-term tubes, repeat tube placement, and older age at the time of tube placement are associated with a higher risk of perforation.[1][11]

- Blockage of the tympanostomy tube (7-10%)[1][11]

- Formation of granulation tissue (4-5%)[1][11]

- Tympanostomy tube falls out early (3.9-4%)[1][11]

- Tympanostomy tube shifts from the eardrum into the middle ear (0.5%)[1][11]

Long term effects include visible changes to the eardrum such as tympanosclerosis, cholesteatoma, focal atrophy, or retraction pockets.[1][11] These changes usually resolve on their own and do not usually require medical treatment or result in hearing problems that are clinically significant.[1][12]

Surgical intervention may be required in cases of persistent perforation or retained tympanostomy tubes. Persistent perforations are corrected via tympanoplasty with an 80-90% success rate.[1] Most tympanostomy tubes fall out on their own as the eardrum heals; however, when tubes remain after 2–3 years they are often removed to prevent complications.[13]

Procedure

[edit]Myringotomy with insertion of tympanostomy tubes is performed by an ENT doctor (otolaryngologist) and is one of the most common pediatric surgical procedures, accounting for more than 20% of all ambulatory pediatric surgeries in 2006.[1] Although myringotomy with tympanostomy tube insertion can be performed in-office under local anesthesia for adolescents and adults, children or any patient who may have difficulty lying still during the procedure require general anesthesia.[6][14]

During the procedure, a small incision is made to the eardrum using either a myringotomy knife or a CO2 laser.[6][15] The middle ear is then usually washed out thoroughly with saline before the tympanostomy tubes are placed. Antibiotic drops are commonly used during surgery once tubes are placed but are not routinely prescribed for use following surgery unless recommended by a doctor for individual reasons.[1][6][9]

Following surgery, it is suggested that children keep their ears dry for the first two weeks to help prevent complications. After two weeks children do not need to wear earplugs when swimming or to take other measures to prevent water from getting in their ears as there is minimal reduction in adverse effects.[1][16] It is approximated that a child would need to wear ear plugs for 2.8 years to prevent one additional ear infection.[16]

Outcome

[edit]Tympanostomy tubes generally remain in the eardrum for six months to two years, and about 14% of children will require tympanostomy tubes more than once.[1] The eardrum usually closes without a residual hole at the tube site but in a small number of cases a perforation can persist.[1] For children with otitis media with effusion (glue ear), tympanostomy tubes decrease the prevalence of effusions by 33% and improve hearing by 5-12 decibels, within 1–3 months of the procedure. There is no long-term benefit for hearing by 12–24 months after the procedure.[1][6]

For children with frequent episodes of acute otitis media (ear infection), there is debate about the effectiveness of tympanostomy tubes in reducing rates of infections. There is consensus, however, on the beneficial role of tympanostomy tubes in allowing for drainage of infections and offering direct access to the middle ear with antibiotic drops.[1] This aids healthcare providers in identifying the cause of the infection so they can better treat it and decrease the need for systemic antibiotic use.[1][6]

History

[edit]The first myringotomy dates back to 1649 when French anatomist Jean Riolan noticed an improvement in his hearing after intentionally perforating his eardrum with a spoon.[17] For nearly two hundred years, scientists would study and debate the potential benefits of myringotomy before German scientists Martell Frank and Gustav Lincke had the first documented use of tympanostomy tubes in 1845. These scientists used an approximately 6mm long gold tube in an attempt to prevent the eardrum from closing after myringotomy.[18]

From 1845 to 1875, seven different types of tympanostomy tubes were manufactured and made of materials including rubber, silver, aluminum, and gold. These tubes were not widely used or accepted due to complications including falling into the middle ear, falling out of the ear, and the tubes getting plugged.[18] In 1952, tympanostomy tubes would make a return when American otolaryngologist Beverly Armstrong introduced them as a new treatment for chronic secretory otitis media. This would lead to numerous types of tympanostomy tubes being developed and studied throughout the 20th century.[18]

Today, silicone and fluoroplastic tympanostomy tubes are more commonly used than metal tubes made from stainless steel, titanium, or gold.[2] Research on ways to reduce biofilm formation on tympanostomy tubes, such as coating the tubes with antibiotics before placement to help prevent tube blockage or infection, has been started, but there is not enough data to determine its effectiveness.[2] Dissolvable tubes are also being explored as potential alternatives for current tube materials.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Rosenfeld, Richard M.; Tunkel, David E.; Schwartz, Seth R.; Anne, Samantha; Bishop, Charles E.; Chelius, Daniel C.; Hackell, Jesse; Hunter, Lisa L.; Keppel, Kristina L.; Kim, Ana H.; Kim, Tae W.; Levine, Jack M.; Maksimoski, Matthew T.; Moore, Denee J.; Preciado, Diego A. (9 February 2022). "Clinical Practice Guideline: Tympanostomy Tubes in Children (Update)". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 166 (1_suppl): S1–S55. doi:10.1177/01945998211065662. ISSN 1097-6817. PMID 35138954. S2CID 246700402 – via PubMed.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Nagar, Rashi R; Deshmukh, Prasad T (11 October 2022). "An Overview of the Tympanostomy Tube". Cureus. 14 (10): e30166. doi:10.7759/cureus.30166. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 9647717. PMID 36397911.

- ^ Goodman, David C.; Morden, Nancy E.; Ralston, Shawn L.; Chang, Chiang-Hua; Parker, Devin M.; Weinstein, Shelsey J. (11 December 2013), "Common Surgical Procedures", The Dartmouth Atlas of Children’s Health Care in Northern New England [Internet], The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ Venekamp, Roderick P; Mick, Paul; Schilder, Anne GM; Nunez, Desmond A (9 May 2018). Cochrane ENT Group (ed.). "Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2019 (6): CD012017. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012017.pub2. PMC 6494623. PMID 29741289.

- ^ "Glue ear". National Deaf Children's Society. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Spaw, Mark; Camacho, Macario (2024), "Tympanostomy Tube", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 33351417, retrieved 12 February 2024

- ^ a b c Lieberthal, AS; Carroll, AE; Chonmaitree, T; Ganiats, TG; Hoberman, A; Jackson, MA; Joffe, MD; Miller, DT; Rosenfeld, RM; Sevilla, XD; Schwartz, RH; Thomas, PA; Tunkel, DE (March 2013). "The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media". Pediatrics. 131 (3): e964-99. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3488. PMID 23439909.

- ^ Canadian Society of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery (2023). "Otolaryngology: Nine tests and treatments to question in pediatric Orolaryngology". Choosing Wisely Canada. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Syed, Mohammed Iqbal; Suller, Sharon; Browning, George G.; Akeroyd, Michael A. (2013). "Interventions for the prevention of postoperative ear discharge after insertion of ventilation tubes (grommets) in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD008512. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008512.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 11612853. PMID 23633358.

- ^ a b Venekamp, Roderick P.; Javed, Faisal; van Dongen, Thijs Ma; Waddell, Angus; Schilder, Anne Gm (2016). "Interventions for children with ear discharge occurring at least two weeks following grommet (ventilation tube) insertion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD011684. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011684.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6465056. PMID 27854381.

- ^ a b c d e f Kay, David J.; Nelson, Magalie; Rosenfeld, Richard M. (1 April 2001). "Meta-Analysis of Tympanostomy Tube Sequelae". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 124 (4): 374–380. doi:10.1067/mhn.2001.113941. ISSN 0194-5998. PMID 11283489. S2CID 25287112.

- ^ Cayé-Thomasen, Per; Stangerup, Sven-Eric; Jørgensen, Gita; Drozdziewic, Dominika; Bonding, Per; Tos, Mirko (1 August 2008). "Myringotomy Versus Ventilation Tubes in Secretory Otitis Media". Otology & Neurotology. 29 (5): 649–657. doi:10.1097/mao.0b013e318173035b. ISSN 1531-7129. PMID 18520632. S2CID 42756454.

- ^ Michel, Margaret; Nahas, Gabriel; Preciado, Diego (31 August 2020). "Retained Tympanostomy Tubes: Who, What, When, Why, and How to Treat?". Ear, Nose & Throat Journal: 014556132095049. doi:10.1177/0145561320950490. ISSN 0145-5613. PMID 32865460.

- ^ "Ear tube insertion: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Chang, Chan-Wei; Yang, Ya-Wen; Fu, Chong Yau; Shiao, An-Suey (1 January 2012). "Differences between children and adults with otitis media with effusion treated with CO2 laser myringotomy". Journal of the Chinese Medical Association. 75 (1): 29–35. doi:10.1016/j.jcma.2011.10.001. ISSN 1726-4901. PMID 22240534.

- ^ a b Moualed, Daniel; Masterson, Liam; Kumar, Sanjiv; Donnelly, Neil (27 January 2016). Cochrane ENT Group (ed.). "Water precautions for prevention of infection in children with ventilation tubes (grommets)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (1): CD010375. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010375.pub2. PMC 10612140. PMID 26816299.

- ^ Rimmer, Joanne; Giddings, Charles E.; Weir, Neil (19 March 2020). "The History of Myringotomy and Grommets". Ear, Nose & Throat Journal. 99 (1_suppl): 2S–7S. doi:10.1177/0145561320914438. ISSN 0145-5613. PMID 32189517.

- ^ a b c Mudry, Albert (1 February 2013). "The tympanostomy tube: An ingenious invention of the mid 19th century". International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 77 (2): 153–157. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.10.024. ISSN 0165-5876. PMID 23183195.