Muhammad: Difference between revisions

Should not draw the Prophet Mohammad (pbuh). |

|||

| Line 99: | Line 99: | ||

==== Early years in Mecca ==== |

==== Early years in Mecca ==== |

||

<!-- The consensus to include these images of Muhammad emerged after extensive months long discussions and efforts on both sides to balance multiple competing interests. Please do not remove or reposition these images because they are against your religion. Please do not add more images or reposition the current ones to prove a point. To avoid pointless revert-warring, blocking, and page protection, please discuss changes on the talk page. Thank you for contributing to Wikipedia. --> |

<!-- The consensus to include these images of Muhammad emerged after extensive months long discussions and efforts on both sides to balance multiple competing interests. Please do not remove or reposition these images because they are against your religion. Please do not add more images or reposition the current ones to prove a point. To avoid pointless revert-warring, blocking, and page protection, please discuss changes on the talk page. Thank you for contributing to Wikipedia. --> |

||

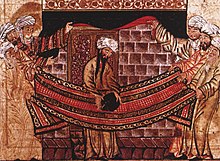

[[Image:Maome.jpg|thumb|220px|right|A [[manuscript]] scene depicts Muhammed preaching the Qur'ān in Mecca.<ref name=maome>{{cite web | publisher=[[Bibliothèque nationale de France]] | url=http://expositions.bnf.fr/livrarab/grands/0_01.htm | title=Le Prophète Mahomet | publication=L'art du livre arabe | accessdate=03-02-2007}}</ref>]] |

|||

[[Image:Siyer-i Nebi 151b.jpg|thumb|200px|right|[[Nakkaş Osman]] [c. 1595]. ''Prophet Muhammad at the Ka'ba, [[The Life of the Prophet]]'' [[Topkapi Palace Museum]], [[Istanbul]] (Inv. 1222/123b). Muhammad's face is veiled, a practice followed in [[Islamic art]] since the 16th century.<ref name="Ali7">Ali, Wijdan. "[http://www2.let.uu.nl/Solis/anpt/ejos/pdf4/07Ali.pdf From the Literal to the Spiritual: The Development of Prophet Muhammad's Portrayal from 13th century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th century Ottoman Art]". In ''Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art'', eds. M. Kiel, N. Landman, and H. Theunissen. No. 7, 1–24. Utrecht, The Netherlands, August 23–28, 1999, p. 7</ref>]] |

[[Image:Siyer-i Nebi 151b.jpg|thumb|200px|right|[[Nakkaş Osman]] [c. 1595]. ''Prophet Muhammad at the Ka'ba, [[The Life of the Prophet]]'' [[Topkapi Palace Museum]], [[Istanbul]] (Inv. 1222/123b). Muhammad's face is veiled, a practice followed in [[Islamic art]] since the 16th century.<ref name="Ali7">Ali, Wijdan. "[http://www2.let.uu.nl/Solis/anpt/ejos/pdf4/07Ali.pdf From the Literal to the Spiritual: The Development of Prophet Muhammad's Portrayal from 13th century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th century Ottoman Art]". In ''Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art'', eds. M. Kiel, N. Landman, and H. Theunissen. No. 7, 1–24. Utrecht, The Netherlands, August 23–28, 1999, p. 7</ref>]] |

||

According to the Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet.<ref name="Watt53-86"> William Montgomery Watt (1953), p. 86 </ref> She was soon followed by Muhammad's ten-year-old cousin [[Ali|Ali ibn Abi Talib]], close friend [[Abu Bakr]], and adopted son [[Zayd ibn Harithah|Zaid]]. The [[identity of first male Muslim|identity of the first male Muslim]] is a controversial subject.<ref name="Watt53-86"/> |

According to the Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet.<ref name="Watt53-86"> William Montgomery Watt (1953), p. 86 </ref> She was soon followed by Muhammad's ten-year-old cousin [[Ali|Ali ibn Abi Talib]], close friend [[Abu Bakr]], and adopted son [[Zayd ibn Harithah|Zaid]]. The [[identity of first male Muslim|identity of the first male Muslim]] is a controversial subject.<ref name="Watt53-86"/> |

||

Revision as of 11:57, 23 February 2008

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

Abu l-Qasim Muhammad ibn ‘Abd Allāh al-Hashimi al-Qurashi (Template:Lang-ar[2] Template:ArabDIN; (Mohammed, Muhammed, Mahomet)[3][4][5] (c. 570 Mecca – June 8, 632 Medina),[6] was the founder of the world religion of Islam and is regarded by Muslims as the last messenger and prophet of

| Part of a series on Islam |

| Allah (God in Islam) |

|---|

|

|

|

.[7] Muslims consider him the restorer of the original, uncorrupted monotheistic faith (islām) of Adam, Abraham and others. They see him as the last and the greatest in a series of prophets of Islam.[8][9][10]

Muhammad and is also regarded as a prophet by the Druze and as a Manifestation of God by the Bahá'í Faith.

He was also active as a diplomat, merchant, philosopher, orator, apostle, legislator, general and reformer.[11]

The most credible source of information for the life of Muhammad is the Qur'an.[12] Next in importance are the historical works by writers of third and fourth century of the Muslim era. [13] Sources on Muhammad’s life concur that he was born ca. 570 CE in the city of Mecca in Arabia.[14] He was orphaned at a young age and was brought up by his uncle, later worked mostly as a merchant, and was married by age 26. At some point, discontented with life in Mecca, he retreated to a cave in the surrounding mountains for meditation and reflection. According to Islamic tradition, it was here at age 40, in the month of Ramadan, where he received his first revelation from God. Three years after this event, Muhammad started preaching these revelations publicly, proclaiming that "God is One", that complete "surrender" to Him (lit. islām)[15] is the only way (dīn),[16] acceptable to God, and that he was a prophet and messenger of God, in the same vein as Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, David, Jesus, and other prophets.[17][18][10]

Muhammad gained few followers early on, and was largely met with hostility from the tribes of Mecca; he was treated harshly and so were his followers. To escape persecution, Muhammad and his followers migrated to Yathrib (Medina)[19] in the year 622. This historic event, the Hijra, marks the beginning of the Islamic calendar. In Medina, Muhammad managed to unite the conflicting tribes, and after eight years of fighting with the Meccan tribes, his followers, who by then had grown to ten thousand, conquered Mecca. In 632, on returning to Medina from his 'Farewell pilgrimage', Muhammad fell ill and died. By the time of his death, most of Arabia had converted to Islam.

The revelations (or Ayats, lit. Signs of God), which Muhammad reported receiving until his death, form the verses of the Qur'an,[20] regarded by Muslims as the “word of God”, around which the religion is based. Besides the Qur'an, Muhammad’s life (sira) and traditions (sunnah) are also upheld by Muslims.

Figurative depictions of Muhammad were a significant part of late medieval Islamic art; however, such depictions were generally limited to secular contexts and to the elite classes who could afford fine art.[21] The taboo on depictions of Muhammad was less stringent during the Ottoman Empire, although his face was often left blank.[22]

Etymology

The name Muhammad literally means "Praiseworthy".[23][24] Within Islam, Muhammad is known as Nabi (Prophet) and Rasul (Messenger). Although the Qur'an sometimes declines to make a distinction among prophets, in Surah 33:40 it singles out Muhammad as the "Seal of the Prophets".[25] The Qur'an also refers to Muhammad as "Ahmad" (Surah 61:6) (Arabic :أحمد), Arabic for "more praiseworthy".

Sources for Muhammad's life

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

From a scholarly point of view, the most credible source providing information on events in Muhammad's life is the Qur'an.[26][12] The Qur'an has some, though very few, casual allusions to Muhammad's life.[12] The Qur'an, however, responds "constantly and often candidly to Muhammad's changing historical circumstances and contains a wealth of hidden data that are relevant to the task of the quest for the historical Muhammad."[18] All or most of the Qur'an was apparently written down by Muhammad's followers while he was alive, but it was, then as now, primarily an orally related document, and the written compilation of the whole Qur'an in its definite form was completed early after the death of Muhammad.[27] The Qur'an in its actual form is generally considered by academic scholars to record the words spoken by Muhammad because the search for variants in Western academia has not yielded any differences of great significance.[28]

Next in importance are the historical works by writers of third and fourth century of the Muslim era. [13] These include the traditional Muslim biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him (the sira and hadith literature), which provide further information on Muhammad's life.[26] The earliest surviving written sira (biographies of Muhammad and quotes attributed to him) is Ibn Ishaq's Sirah Rasul Allah (Life of God's Messenger). Although the original work is lost, portions of it survive in the recensions of Ibn Hisham (Sirah al-Nabawiyyah, Life of the prophet) and Al-Tabari.[29] According to Ibn Hisham, Ibn Ishaq wrote his biography some 120 to 130 years after Muhammad's death. [12] Another early source is the history of Muhammad's campaigns by al-Waqidi (death 207 of Muslim era), Maghazi al-Waqidi, and the work of his secretary Ibn Sa'd (death 230 of Muslim era) Tabaqat Ibn Sa'd.[13] The biographical dictionaries of Ibn al-Athir and Ibn Hajar provide much detail about the contemporaries of Muhammad but add little to our information about Muhammad himself.[30] Lastly, the hadith collections, accounts of the verbal and physical traditions of Muhammad, date from several generations after the death of Muhammad. Western academics view the hadith collections with caution as accurate historical sources.[31]

Many, but not all, scholars accept the accuracy of these biographies, though their accuracy is unascertainable.[12] Studies by J. Schacht and Goldziher has led scholars to distinguish between the traditions touching legal matters and the purely historical ones. According to William Montgomery Watt, in the legal sphere it would seem that sheer invention could have very well happened. In the historical sphere however, aside from exceptional cases, the material may have been subject to "tendential shaping" rather than being made out of whole cloth.[32]

There are a few non-Muslim sources which, according to S. A. Nigosian, confirm the existence of Muhammad. The earliest of these sources date to shortly after 634, and the most interesting of them date to some decades later. These sources are valuable for corroboration of the Qur'anic and Muslim tradition statements.[12]

The Arabian Background

As a result of the general awareness of the material factors underlying the history in the second half of the 20th century, recent biographies of Muhammad have taken a fresh approach by reconstructing the economical, political and social background of the movement initiated by Muhammad. Whether the historian holds that the economical, political and social factors entirely determines the course of events in the rise of a movement like that of Islam, or leaves some room for the religious and ideological aspects of it, historians all agree on the importance of the economical, political and social aspects and aim to read the ideological and religious aspects of Islam in that context. [33]

- Economic basis

The Arabian Peninsula was dominated by volcanic steppes and desert wastes. It was therefore not suitable for agriculture except where the feasibility of irrigation existed (such as in oases and at certain spots high in the mountains). [34][35] Thus the Arabian landscape was dotted with towns and cities, two prominent of which were Mecca and Medina. [36] People of Arabia were either nomadic or sedentary. The latter were the descendants of nomads and had preserved many of the desert-born habits of their ancestors. The nomadic life was based on stock-breeding traveling from one place to another seeking water and pasture for their flocks. Their survival was also to some extent dependent on raiding on caravans or on oasises; thus no crime in the eyes of Baudoin. [35] Agriculture and trade were two important occupations of the sedentary Arabs. Mecca was an important financial center in which operations of considerable complexity were carried out and had created a financial net involving Meccans and many of the surrounding tribes. The Meccan leaders were "skillful in manipulation of credits, shrewed in their experience and interested in lucrative investments from Aden to Gaza or Damascus".[35] Islam was thus born in an atmosphere of high finance. Medina, another important city in Arabia, on the other hand was a large flourishing agricultural settlement. [35]

Some scholars have suggested that the rise of Islam and its subsequent expansions were a result of the hunger caused by a decrease in the water supply in the Arabian steppe. William Montgomery Watt however argues, among other things, that there is no good evidence of any significant deterioration of climatic conditions.[35]

- Tribal solidarity

Communal life is essential for survival in desert conditions. Men need help of each other against the forces of nature and against other human rivals. The tribal grouping was thus enhanced by the need to act as a unit.[37] This unity was based on the bond of kinship by blood. Though divided in various tribes, all the Arabs were somewhat united based on a common language, common poetical tradition, conventions and ideas, and a common descent (all Arabs traced their genealogy to two men named Adnan and Qahtan). According to William Montgomery Watt, this Arabic sense of distinction from other people and superiority over others became important when Muhammad created a political unity among the Arabs in Medina. [38] Fazlur Rahman disagrees arguing, among other things, that "the egalitarianism that it [Islam] presupposes transcends, by its very nature, any 'national' idea". [39]

- Decline of tribal solidarity and growth of individualism

The accumulation of capital and the commercial life of Mecca had however fostered individualism and had created a growing awareness of the existence of individual in separateness from the tribe. This tendency had in turn produced a greater interest in pursuing the problem of cessation of man's individual existence at death: Was death the end? The individualistic tendencies could be observed in the early Islam: Many of the earliest followers of Muhammad decided to convert to Islam despite the disapproval of their clans or even their parents; Muhammad's uncle, Abu Lahab, who joined the opposition against Muhammad.[40]

A new phenomenon which could be observed in the advent of Islam in Mecca was the formation of a sense of unity based on common material interest. Following the Muslim victory over Meccans at the battle of Badr, a kind of "coalition government" was formed among rival tribes in Mecaa against the Muslims. As the coalition was not based on blood kinship, it weakened the bond of kinship by blood thus implicitly provided the opportunity for the later establishment of a wider unity on a new basis.[41]

According to Watt, a major economical change correlated ("absolutely dependent" according to Marxist historians) with the advent of Islam was that:[42]

"In the rise of Mecca to wealth and power we have a movement from nomadic economy to a mercantile and capitalist economy. By the time of Muhammad, however, there had been no readjustment of the social, moral, intellectual, and religous attitudes of the community. These were still the attitudes appropriate to a nomadic community, for the most part. The tension felt by Muhammad and some of his contemporaries was doubtless due ultimately to this contrast between men's conscious attitude and the economic basis of their life.

Biography

Muhammad in Mecca

Genealogy

Muhammad was born into the Quraysh tribe. He was the son of Abd Allah, son of Abd al-Muttalib (Shaiba) son of Hashim (Amr) son of Abd Manaf (al-Mughira) son of Qusai (Zaid) son of Kilab son of Murra son of Ka'b son of Lu'ay son of Ghalib ibn Fahr (Quraysh) son of Malik son of an-Nadr (Qais) son of Kinana son of Khuzaimah son of Mudrikah (Amir) son of Ilyas son of Mudar son of Nizar son of Ma'ad son of Adnan, whom the northern Arabs believe to be their common ancestor. Adnan in turn is said to have been a descendant of Ishmael, son of Abraham.[43]

Childhood

Muhammad was born into the family of Banu Hashim, one of the prominent families of Mecca but the family seems to have not been prosperous during Muhammad's early lifetime.[18][44] Tradition places Muhammad's birth in the Year of the Elephant, commonly identified with 570.[45] Western historians hitherto had accepted the Year of the Elephant to be 570, however according to Watt some new discoveries suggest that the Year of the Elephant might have been 569 or 568.[45] Welch on the other hand holds that the Year of the Elephant should have taken place considerably earlier than 570 and further argues that Muhammad may have been born even later than 570.[18]

Muhammad's birthday is considered by Sunni Muslims to have been the 12th day of the month of Rabi'-ul-Awwal, the third month of the Muslim calendar.[46] Shi'a Muslims believe it to have been the dawn of 17th of the month of Rabi'-ul-Awwal.[47]

Muhammad's father, Abdullah, died almost six months before he was born.[48] According to the tradition, soon after Muhammad's birth, he was sent to live with a Bedouin family in the desert as the desert-life was considered healthier for infants. Muhammad stayed with his foster-mother, Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb, and her husband until he was two years old. Some western scholars of Islam have rejected the historicity of this tradition.[49] At the age of six, Muhammad lost his mother Amina to illness and he became fully orphaned.[50] He was subsequently brought up for two years under the guardianship of his paternal grandfather Abd al-Muttalib, of the Banu Hashim clan of the Quraysh tribe. When he was eight years of age, his grandfather also died. Muhammad now came under the care of his uncle Abu Talib, the new leader of the Hashim clan of Hashim tribe.[45] According to Watt, because of the general disregard of the guardians in taking care of the weak members of the tribes in Mecca in sixth century, "Muhammad's guardians saw that he did not starve to death, but it was hard for them to do more for him, especially as the fortunes of the clan of Hashim seems to have been declining at that time."[51]

Mecca was a thriving commercial center. There was an important shrine in Mecca (now called the Kaaba) that housed statues of many Arabian gods.[52] Merchants from various tribes would visit Mecca during the pilgrimage season.[52] While still in his teens, Muhammad began accompanying his uncle on trading journeys to Syria gaining some experience in commercial career; the only career open to Muhammad as an orphan.[51]

Middle years

Little is known of Muhammad during his youth, and from the fragmentary information that is available, it is hard to separate history from legend.[53] It is known that he became a merchant and "was involved in trade between the Indian ocean and the Mediterranean Sea."[54] He was given the nickname "Al-Amin" (Arabic: الامين), meaning "faithful, trustworthy" and was sought out as an impartial arbitrator.[18][14][55] His reputation attracted a proposal from Khadijah, a forty-year-old widow in 595.[54] Muhammad consented to the marriage, which by all accounts was a happy one.

According to the Muslim tradition, the young Muhammad played a role in the restoration of the Kaaba, after parts of it had been destroyed by one of Mecca's frequent flash floods.[56] When the reconstruction was almost done, disagreements arose as to who would have the honor of lifting the Black Stone into place and different clans were about to take up arms against each other. One of the elders suggested they take the advice of the first one who entered the gates of the Haram. This happened to be Muhammad. He spread out his cloak, put the stone in the middle and had members of the four major clans raise it to its destined position. The cloak became an important symbol for later poets and writers.[57]

Beginnings of the Qur'an

Muhammad often retreated to Mount Hira near Mecca. Islamic tradition holds that the angel Gabriel began communicating with him here in the year 610 and commanded Muhammad to recite the following verses:[58]

Proclaim! (or read!) in the name of thy Lord and Cherisher, Who created- Created man, out of a (mere) clot of congealed blood: Proclaim! And thy Lord is Most Bountiful,- He Who taught (the use of) the pen,- Taught man that which he knew not.(Surah 96:1-5)

Upon receiving his first revelations he was deeply distressed. When he returned home he related the event to his wife Khadijah, and told her that he contemplated throwing himself off the top of a mountain.[59] He was consoled and reassured by Khadijah and her Christian cousin, Waraqah ibn Nawfal. This was followed by a pause of three years during which Muhammad gave himself up further to prayers and spiritual practices. When the revelations resumed he was reassured and commanded to begin preaching (Surah 93:1-11).[60]

According to Welch, these revelations were accompanied by mysterious seizures as the reports are unlikely to have been forged by later Muslims.[18] Muhammad was confident that he could distinguish his own thoughts from these messages.[61]

Early years in Mecca

According to the Muslim tradition, Muhammad's wife Khadija was the first to believe he was a prophet.[63] She was soon followed by Muhammad's ten-year-old cousin Ali ibn Abi Talib, close friend Abu Bakr, and adopted son Zaid. The identity of the first male Muslim is a controversial subject.[63]

Around 613, Muhammad began to preach amongst Meccans most of whom ignored it and a few mocked him, while some others became his followers. There were three main groups of early converts to Islam: younger brothers and sons of great merchants; people who had fallen out of the first rank in their tribe or failed to attain it; and the weak, mostly unprotected foreigners..[64]

According to Ibn Sad, in this period, the Quraysh "did not criticize what he [Muhammad] said… When he passed by them as they sat in groups, they would point out to him and say "There is the youth of the clan of Abd al-Muttalib who speaks (things) from heaven."[65] The Qur'anic exegesis however maintained that the persecution of Muslims began as soon as Muhammad began preaching in public.[66] According to Welch, the Qur'anic verses at this time were not "based on a dogmatic conception of monotheism but on a strong general moral and religious appeal". Its key themes include the moral responsibility of man towards his creator; the resurrection of dead, God's final judgment followed by vivid descriptions of the tortures in hell and pleasures in Paradise; use of the nature and wonders of everyday life, particularly the phenomenon of man, as signs of God to show the existence of a greater power who will take into account the greed of people and their suppression of the poor. Religious duties required of the believers at this time were few: belief in God, asking for forgiveness of sins, offering frequent prayers, assisting others particularly those in need, rejecting cheating and the love of wealth (considered to be significant in the commercial life of Mecca), being chaste and not to kill new-born girls.[18]

Opposition in Mecca

According to Ibn Sad, the opposition in Mecca started when Muhammad delivered verses that "spoke shamefully of the idols they [the Meccans] worshiped other than …[God] and mentioned the perdition of their fathers who died in disbelief."[67] According to Watt, as the ranks of Muhammad's followers swelled, he became a threat to the local tribes and the rulers of the city, whose wealth rested upon the Kaaba, the focal point of Meccan religious life, which Muhammad threatened to overthrow. Muhammad’s denunciation of the Meccan traditional religion was especially offensive to his own tribe, the Quraysh, as they were the guardians of the Ka'aba.[64]

The great merchants tried (but failed) to come to some arrangements with Muhammad in exchange for abandoning his preaching. They offered him admission into the inner circle of merchants and establishing his position in the circle by an advantageous marriage.[64] Some western scholars suggest that the opposition became an open breach after the incident of the satanic verses (see below).[68]

Tradition records at great length the persecution and ill-treatment of Muhammad and his followers.[18] Sumayya bint Khubbat, a slave of Abū Jahl and a prominent Meccan leader, is famous as the first martyr of Islam, having been killed with a spear by her master when she refused to give up her faith. Bilal, another Muslim slave, was tortured by Umayya ibn khalaf who placed a heavy rock on his chest to force his conversion.[69][70] Apart from insults, Muhammad was protected from physical harm due to belonging to the Banu Hashim.[71][72]

In 615, some of Muhammad's followers emigrated to the Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum and founded a small colony there under the protection of the Christian Ethiopian king.[18] While the traditions view the persecutions of Meccans to have played the major role in the emigration, William Montgomery Watt states "there is reason to believe that some sort of division within the embryonic Muslim community played a role and that some of the emigrants may have gone to Abyssinia to engage in trade, possibly in competition with prominent merchant families in Mecca."[18]

The earliest surviving traditions describe Muhammad's involvement at this time in an episode that has come to be known as the "Story of the Cranes" -- a story that some scholars have dubbed the "satanic verses." The account holds that Muhammad pronounced a verse acknowledging the existence of three Meccan goddesses considered to be the daughters of Allah, praising them, and appealing for their intercession. According to these accounts, Muhammad later retracted the verses, saying Gabriel had instructed him to do so.[73] Islamic scholars vigorously objected to the historicity of the incident as early as the tenth century CE. [74] In any event, the relations between the Muslims and their pagan fellow-tribesmen rapidly deteriorated.

According to tradition, the leaders of Makhzum and Abd Shams, two important clans of Quraysh, declared a public boycott against the clan of Banu Hashim, their commercial rival, in order to put pressure on the clan to withdraw its protection from Muhammad. The boycott lasted for three years but eventually collapsed mainly because it was not achieving its purpose.[75][76]

Last years in Mecca

In 619, the "year of sorrows," both Muhammad's wife Khadijah and his uncle Abu Talib died. With the death of Abu Talib, the leadership of the clan of Banu Hashim was passed to Abu Lahab who was an inveterate enemy of Muhammad. Soon afterwards Abu Lahab withdrew the clan's protection from Muhammad. This placed Muhammad under the danger of death since the withdrawal of clan protection implied that the blood revenge for his killing would not be exacted. Muhammad then tried to find a protector for himself in another important city in Arabia, Ta'if, but his effort failed and further brought him into physical danger.[76][18] Muhammad was forced to return to Mecca. A Meccan man named Mut'im b. Adi (and the protection of the tribe of Banu Nawfal) made it possible for him safely to re-enter his native city.[18][76]

Many people were visiting Mecca on business or as pilgrims to the Kaaba. Muhammad took this opportunity to look for a new home for himself and his followers. After several unsuccessful negotiations, he found hope with some men from Yathrib (later called Medina).[18] The Arab population of Yathrib were somewhat familiar with monotheism because a Jewish community existed in that city.[18]

Isra and Mi'raj

Some time in 620, Muhammad told his followers that he had experienced the Isra and Miraj, a miraculous journey said to have been accomplished in one night along with the angel Gabriel. In the first part of the journey, the Isra, he is said to have travelled from Mecca to "the farthest mosque" (in Arabic: masjid al-aqsa), which Muslims usually identify with the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem.In the second part, the Miraj, Muhammad is said to have toured heaven and hell, and spoken with earlier prophets, such as Abraham, Moses, and Jesus.[77]

Ibn Ishaq, author of first biography of Muhammad, presents this event as a spiritual experience while later historians like Al-Tabari and Ibn Kathir present it as a physical journey.[77] Some western scholars of Islam hold that the oldest Muslim tradition identified the journey as one traveled through the heavens from the sacred enclosure at Mecca to the celestial Kaʿba (heavenly prototype of the Ka'ba); but later tradition identified Muhammad's journey from Mecca to the abode of sanctuary (bayt al-maqdis) in Jerusalem.[78]

Muhammad in Medina

Hijra to Medina

A delegation from Medina, consisting of the representatives of the twelve important clans of Medina, invited Muhammad as a neutral outsider to Medina to serve as the chief arbitrator for the entire community.[79][80] There was fighting in Yathrib mainly involving its Arab and Jewish inhabitants for around a hundred years before 620.[79] The recurring slaughters and disagreements over the resulting claims, especially after the battle of Bu'ath in which all the clans were involved, made it obvious to them that the tribal conceptions of blood-feud and an eye for an eye were no longer workable unless there was one man with authority to adjudicate in disputed cases.[79] The delegation from Medina pledged themselves and their fellow-citizens to accept Muhammad into their community and physically protect him as one of themselves.[18]

Muhammad instructed his followers to emigrate to Medina until virtually all of his followers had left Mecca. Being alarmed at the departure of Muslims, according to the tradition, the Meccans plotted to assassin Muhammad. With the help of Ali, however, Muhammad fooled the Meccans who were watching him, and secretly slipped away from the town.[81] By 622, Muhammad had emigrated to Medina, then known as Yathrib, a large agricultural oasis. [18] Following the emigration, the Meccans seized the properties of the Muslim emigrants in Mecca.[82]

Among the things Muhammad did in order to settle down the longstanding grievances among the tribes of Medina was drafting a document known as the Constitution of Medina (date debated), "establishing a kind of alliance or federation" among the eight Medinan tribes and Muslim emigrants from Mecca, which specified the rights and duties of all citizens and the relationship of the different communities in Medina (including that of the Muslim community to other communities specifically the Jews and other "Peoples of the Book").[79][80] The community defined in the Constitution of Medina, umma, had a religious outlook but was also shaped by the practical considerations and substantially preserved the legal forms of the old Arab tribes.[18] Muhammad also temporarily adopted some features of the Jewish worship and customs such as fasting on the Yom Kippur day. According to Alford Welch, The Jewish practice of having three daily prayer rituals appears to have been a factor in the introduction of the Islamic midday prayer (previously Muhammad was keeping the morning and evening prayers). Welch thinks that Muhammad's adoption of facing north towards Jerusalem when performing the daily prayers (qibla) however need not to necessarily be a borrowing from the Jews as the reports about the direction of prayer before migration to Medina are contradictory and further this direction of prayer was also practiced among other groups in Arabia. Welch holds that Muhammad hoped to win over the Jews by adopting these customs. [18]

The first group of pagan converts to Islam in Medina were the clans who had not produced great leaders for themselves but had suffered from warlike leaders from other clans. This was followed by the general acceptance of Islam by the pagan population of Medina, apart from some exception. This was according to Ibn Ishaq influenced by the conversion of Sa'd ibn Muadh, one of the prominent leaders in Medina to Islam. The Jewish clans however kept aloof from Islam though in the course of time there were a few converts from them.[83] After his migration to Medina, Muhammad's attitude towards Christians and Jews changed. Norman Stillman states:[84]

During this fateful time, fraught with tension after the Hidjra [migration to Medina], when Muhammad encountered contradiction, ridicule and rejection from the Jewish scholars in Medina, he came to adopt a radically more negative view of the people of the Book who had received earlier scriptures. This attitude was already evolving in the third Meccan period as the Prophet became more aware of the antipathy between Jews and Christians and the disagreements and strife amongst members of the same religion. The Qur'an at this time states that it will "relate [correctly] to the Children of Israel most of that about which they differ" (XXVII, 76).

According to Welch, the Jewish opposition to Muhammad appears to have caused the change of the direction of prayer (qibla) from Jerusalem to the ancient sanctuary of the Ka'baa in Mecca in the second year after the emigration. The qur'an refers to this incident in verses Qur'an 2:142-150.[18]

Beginnings of armed conflict

Economically uprooted and with no available profession besides that of arms, the Muslim migrants turned to raiding Meccan caravans for their livelihood, thus initiating armed conflict between the Muslims and Mecca.[85][86][87][88] Muhammad delivered Qur'anic verses permitting the Muslims to fight the Meccans (see Qur'an 22:39–40).[89] These attacks provoked and pressured Mecca by interfering with trade, and allowed the Muslims to acquire wealth, power and prestige while working toward their ultimate goal of inducing Mecca's submission to the new faith.[90][91]

In March of 624, Muhammad led some three hundred warriors in a raid on a Meccan merchant caravan. The Muslims set an ambush for the Meccans at Badr.[92] Aware of the plan, the Meccan caravan eluded Muslims. Meanwhile a force from Mecca was sent to protect the caravan. The force did not return home upon hearing that the caravan was safe. The battle of Badr began in March of 624.[93] Though outnumbered more than three to one, the Muslims won the battle, killing at least forty-five Meccans and taking seventy prisoners for ransom; only fourteen Muslims died. They had also succeeded in killing many of the Meccan leaders, including Abu Jahl.[94] Muhammad himself did not fight, directing the battle from a nearby hut alongside Abu Bakr.[95] In the weeks following the battle, Meccans visited Medina in order to ransom captives from Badr. Many of these had belonged to wealthy families, and were likely ransomed for a considerable sum. Those captives who were not sufficiently influential or wealthy were usually freed without ransom. Muhammad's decision was that those who were wealthy but did not ransom themselves should be killed.[96][97] Muhammad ordered the immediate execution of two men without entertaining offers for their release.[97] One of the men, Uqba ibn Abu Mu'ayt, had written verses about Muhammad, and the other had said that his own stories about Persians were as good as the tales of the Qur'an.[96] The raiders had won much booty, and the battle helped to stabilize the Medinan community.[98] Muhammad and his followers saw in the victory a confirmation of their faith. Cite error: A <ref> tag is missing the closing </ref> (see the help page).

With the early general conversion of Medinian pagans to Islam, the pagan opposition in Medina was never of prime importance in the affairs of Medina. Those remaining pagans in Medina were very bitter about the advance of Islam. In particular Asma bint Marwan and Abu Afak had composed verses taunting and insulting some of the Muslims. These two were assassinated and Muhammad did not disapprove of it. No one dared to take vengeance on them, and some of the members of the clan of Asma bint Marwan who had previously converted to Islam in secret, now professed Islam openly. This marked an end to the overt opposition to Muhammad among the pagans in Medina.[99]

Muhammad expelled from Medina the Banu Qaynuqa, one of the three main Jewish tribes.[18] Jewish opposition "may well have been for political as well as religious reasons".[100] On religious grounds, the Jews were skeptical of the possibility of a non-Jewish prophet,[101] and also had concerns about possible incompatibilities between the Qur'an and their own scriptures.[101][102] The Qur'an's response regarding the possibility of a non-Jew being a prophet was that Abraham was not a Jew. The Qur'an also stated that it was "restoring the pure monotheism of Abraham which had been corrupted in various, clearly specified, ways by Jews and Christians".[101] According to Francis Edward Peters, "The Jews also began secretly to connive with Muhammad's enemies in Mecca to overthrow him."[103]

Following the battle of Badr, Muhammad also made mutual-aid alliances with a number of Bedouin tribes to protect his community from attacks from the northern part of Hijaz.[18]

Conflict with Mecca

| Timeline of Muhammad | |

|---|---|

| Important dates and locations in the life of Muhammad | |

| c. 569 | Death of his father, `Abd Allah |

| c. 570 | Possible date of birth, April 20: Mecca |

| 576 | Death of Mother |

| 578 | Death of Grandfather |

| c. 583 | Takes trading journeys to Syria |

| c. 595 | Meets and marries Khadijah |

| 610 | First reports of Qur'anic revelation |

| c. 610 | Appears as Prophet of Islam |

| c. 613 | Begins spreading message of Islam publicly |

| c. 614 | Begins to gather following in Mecca |

| c. 615 | Emigration of Muslims to Ethiopia |

| 616 | Banu Hashim clan boycott begins |

| c. 618 | Medinan Civil War |

| 619 | Banu Hashim clan boycott ends |

| 619 | The year of sorrows: Khadijah and Abu Talib die |

| c. 620 | Isra and Miraj |

| 622 | Emigrates to Medina (Hijra) |

| 624 | Battle of Badr: Muslims defeat Meccans |

| 624 | Expulsion of Banu Qaynuqa |

| 625 | Battle of Uhud: Meccans defeat Muslims |

| 625 | Expulsion of Banu Nadir |

| 626 | Attack on Dumat al-Jandal (Syria) |

| 627 | Battle of the Trench |

| 627 | Destruction of Banu Qurayza |

| 627 | Subjugation of Dumat al-Jandal |

| 628 | Treaty of Hudaybiyya |

| c. 628 | Gains access to Meccan shrine Kaaba |

| 628 | Conquest of the Khaybar oasis |

| 629 | First hajj pilgrimage |

| 629 | Attack on Byzantine empire fails: Battle of Mu'tah |

| 630 | Attacks and bloodlessly captures Mecca |

| c. 630 | Battle of Hunayn |

| c. 630 | Siege of Taif |

| 630 | Conquest of Mecca |

| c. 631 | Rules most of the Arabian peninsula |

| c. 632 | Attacks the Ghassanids: Tabuk |

| 632 | Farewell hajj pilgrimage |

| 632 | Death (June 8): Medina |

The attack at Badr committed Muhammad to total war with Meccans, who were now anxious to avenge their defeat. To maintain their economic prosperity, the Meccans needed to restore their prestige, which had been lost at Badr.[104] The Meccans sent out a small party for a raid on Medina to restore confidence and reconnoiter. The party retreated immediately after a surprise and speedy attack but with minor damages; there was no combat.[105] In the ensuing months, Muhammad led expeditions on tribes allied with Mecca and sent out a raid on a Meccan caravan.[106] Abu Sufyan subsequently gathered an army of three thousand men and set out for an attack on Medina.[107] They were accompanied by some prominent women of Mecca, such as Hind bint Utbah, Abu Sufyan's wife, who had lost family members at Badr. These women provided encouragement in keeping with Bedouin custom, calling out the names of the dead at Badr.[108]

A scout alerted Muhammad of the Meccan army's presence and numbers a day later. The next morning, at the Muslim conference of war, there was dispute over how best to repel the Meccans. Muhammad and many of the senior figures suggested that it would be safer to fight within Medina and take advantage of its heavily fortified strongholds. Younger Muslims argued that the Meccans were destroying their crops, and that huddling in the strongholds would destroy Muslim prestige. Muhammad eventually conceded to the wishes of the latter, and readied the Muslim force for battle. Thus, Muhammad led his force outside to the mountain of Uhud (where the Meccans had camped) and fought the Battle of Uhud on March 23.[109][110]

Although the Muslim army had the best of the early encounters, indiscipline on the part of strategically placed archers led to a Muslim defeat, with 75 Muslims killed. However, the Meccans failed to achieve their aim of destroying the Muslims completely.[111] The Meccans did not occupy the town and withdrew to Mecca because they could not attack on Muhammad's position again for military loss, low morale and possibility of Muslim resistance in the town. There was also hope that Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy leading a group of Muslims in Medina could be won over by diplomacy.[112] Following the defeat, Muhammad's detractors in Medina said that if the victory at Badr was proof of the genuineness of his mission, then the defeat at Uhud was proof that his mission was not genuine.[113] Muhammad subsequently delivered Qur'anic verses Qur'an 3:133-135 and Qur'an 3:160-162 indicating that the loss, however, was partly a punishment for disobedience and partly a test for steadfastness.[114]

The rousing of the nomads

In the battle of Uhud, the Meccans had collected all the available men from Quraysh and the neighboring tribes friendly to them but had not succeeded in the destruction of the Muslim community. In order to raise a more powerful army, Abu Sufyan attracted the support of the great nomadic tribes to the north and east of Medina, using propaganda about Muhammad's weakness, promises of booty, memories of the prestige of Quraysh and straight bribes.[115]

Muhammad's policy in the next two years after the battle of Uhud was to prevent alliances against him as much as he could. Whenever alliances of tribesmen against Medina was formed, he sent out an expedition to break it up.[115] When Muhammad heard of men massing with hostile intentions against Medina, he reacted with severity.[116] One example is the assassination of Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf, a member of the Jewish tribe of Banu Nadir who had gone to Mecca and written poems that had helped rouse the Meccans' grief, anger and desire for revenge after the battle of Badr (see the main article for other reasons for killing of Ka'b given in the historiographical sources).[117] Around a year later, Muhammad expelled the Jewish Banu Nadir from Medina (see the main article for details).[118]

Muhammad's attempts to prevent formation of confederation against him was not successful though he was able to increase his own forces and stop many tribes from joining the confederation.[119]

Siege of Medina

Abu Sufyan, the military leader of Quraysh, with the help of Banu Nadir, the exiled Jewish tribe from Medina, had mustered a force of size 10000 men. Muhammad was able to prepare a force of about 3000 men. He had however adopted a new form of defense, unknown in Arabia at that time: Muslims had dug a trench wherever Medina lay open to cavalry attack. The idea is credited to a Persian convert to Islam, Salman. The siege of Medina began on 31 March 627 and lasted for two weeks.[120] Abu Sufyan's troops were unprepared for the fortifications they were confronted with, and after an ineffectual siege, the coalition decided to go home.[121] The Qur'an discusses this battle in verses Qur'an 33:9-33:27. [66]

During the Battle of the Trench, the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza who were located at the south of Medina were charged with treachery. After the retreat of the coalition, Muslims besieged Banu Qurayza, the remaining major Jewish tribe in Medina. The Banu Qurayza surrendered and all the men, apart from a few who converted to Islam, were beheaded, while all the women and children were enslaved.[122][123] In dealing with Muhammad's treatment of the Jews of Medina, aside from political explanations, Arab historians and biographers have explained it as "the punishment of the Medina Jews, who were invited to convert and refused, perfectly exemplify the Quran's tales of what happened to those who rejected the prophets of old."[124] F.E. Peters, a western scholar of Islam, states that Muhammad's treatment of Jews of Medina was essentially political being prompted by what Muhammad read as treasonous and not some transgression of the law of God.[103] Peters adds that Muhammad was possibly emboldened by his military successes and also wanted to push his advantage. Economical motivations according to Peters also existed since the poorness of the Meccan migrants was a source of concern for Muhammad.[125] Peters argues that Muhammad's treatment of the Jews of Medina was "quite extraordinary", "matched by nothing in the Qur'an", and is "quite at odds with Muhammad's treatment of the Jews he encountered outside Medina."[103] According to Welch, Muhammad's treatment of the three major Jewish tribes brought Muhammad closer to his goal of organizing a community strictly on a religious basis. He adds that some Jews from other families were, however, allowed to remain in Medina. [18]

In the siege of Medina, the Meccans had exerted their utmost strength towards the destruction of the Muslim community. Their failure resulted in a significant loss of prestige; their trade with Syria was gone.[126] Following the battle of trench, Muhammad made two expeditions to the north which ended without any fighting. [18] While returning from one of these two expeditions (or some years earlier according to other early accounts), an accusation of adultery was made against Aisha, Muhammad's wife. Aisha was exonerated from the accusations when Muhammad announced that he had received a revelation confirming Aisha's innocence and directing that charges of adultery be supported by four eyewitnesses.[127]

Truce of Hudaybiyya

Although Muhammad had already delivered Qur'anic verses commanding the Hajj,[128] the Muslims had not performed it due to the enmity of the Quraysh. In the month of Shawwal 628, Muhammad ordered his followers to obtain sacrificial animals and to make preparations for a pilgrimage (umra) to Mecca, saying that God had promised him the fulfillment of this goal in a vision where he was shaving his head after the completion of the Hajj.[129] According to Lewis, Muhammad felt strong enough to attempt an attack on Mecca, but on the way it became clear that the attempt was premature and the expedition was converted into a peaceful pilgrimage.[130] Andrae disagrees, writing that the Muslim state of ihram (which restricted their freedom of action) and the paucity of arms carried indicated that the pilgrimage was always intended to be pacific.[131] Upon hearing of the approaching 1,400 Muslims, the Quraysh sent out a force of 200 cavalry to halt them. Muhammad evaded them by taking a more difficult route, thereby reaching al-Hudaybiyya, just outside of Mecca.[132] According to Watt, although Muhammad's decision to make the pilgrimage was based on his dream but he was at the same time demonstrating to the pagan Meccans that Islam does not threaten the prestige of their sanctuary, and that Islam was an Arabian religion. [133]

Negotiations commenced with emissaries going to and from Mecca. While these continued, rumors spread that one of the Muslim negotiators, Uthman bin al-Affan, had been killed by the Quraysh. Muhammad responded by calling upon the pilgrims to make a pledge not to flee (or to stick with Muhammad, whatever decision he made) if the situation descended into war with Mecca. This pledge became known as the "Pledge of Good Pleasure" (Arabic: بيعة الرضوان , bay'at al-ridhwān) or the "Pledge under the Tree." News of Uthman's safety, however, allowed for negotiations to continue, and a treaty scheduled to last ten years was eventually signed between the Muslims and Quraysh.[132][134] The main points of treaty were the following:

- The two parties and their allies should desist from hostilities against each other.[135]

- Muhammad, should not perform Hajj this year but in the next year, Mecca will be evacuated for three days for Muslims to perform Hajj.[136]

- Muhammad should send back any Meccan who had gone to Medina without the permission of his or her protector (according to William Montgomery Watt, this presumably refers to minors or women).[136]

- It was allowed for both Muhammad and the Quraysh to enter into alliance with others.[136]

Many Muslims were not satisfied with the terms of the treaty. However, the Qur'anic sura "Al-Fath" (The Victory) (Qur'an 48:1-29) assured the Muslims that the expedition from which they were now returning must be considered a victorious one.[137] It was only later that Muhammad's followers would realise the benefit behind this treaty. These benefits, according to Welch, included the inducing of the Meccans to recognise Muhammad as an equal; a cessation of military activity posing well for the future; and gaining the admiration of Meccans who were impressed by the incorporation of the pilgrimage rituals.[18]

After signing the truce, Muhammad made an expedition against the Jewish oasis of Khaybar. The explanation given by western scholars of Islam for this attack ranges from the presence of the Banu Nadir in Khaybar, who were inciting hostilities along with neighboring Arab tribes against Muhammad, to deflecting from what appeared to some Muslims as the inconclusive result of the truce of Hudaybiyya, increasing Muhammad's prestige among his followers and capturing booty.[107][138] According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad also sent letters to many rulers of the world, asking them to convert to Islam (the exact date are given variously in the sources).[139][140][18] Hence he sent messengers (with letters) to Heraclius of the Byzantine Empire (the eastern Roman Empire), Chosroes of Persia, the chief of Yemen and to some others.[139][140] In the years following the truce of Hudaybiyya, Muhammad sent his forces against the Arabs of Mu'tah on Byzantine soil in Transjordania since according to the tradition, they had murdered Muhammad's envoy. F. Buhl however holds that the real reason "seems to have been that he wished to bring the (Christian or pagan) Arabs living there under his control." Muslims were defeated in this battle. [141]

Final years

Conquest of Mecca

The truce of Hudaybiyya had been enforced for two years.[142][143] The tribe of Khuz'aah had a friendly relationship with Muhammad, while on the other hand their enemies, the Banu Bakr, had an alliance with the Meccans.[142][143] A clan of the Bakr made a night raid against the Khuz'aah, killing a few of them.[142][143] The Meccans helped their allies (i.e., the Banu Bakr) with weapons and, according to some sources, a few Meccans also took part in the fighting.[142] After this event, Muhammad sent a message to Mecca with three conditions, asking them to accept one of them. These were the following[144]

- The Meccans were to pay blood-money for those slain among the Khuza'ah tribe, or

- They should have nothing to do with the Banu Bakr, or

- They should declare the truce of Hudaybiyya null.

The Meccans replied that they would accept only the third condition.[144] However, soon they realized their mistake and sent Abu Safyan to renew the Hudaybiyya treaty, but now his request was declined by Muhammad. Muhammad began to prepare for a campaign.[145]

In 630, Muhammad marched on Mecca with an enormous force, said to number more than ten thousand men. With minimal casualties, Muhammad took control of Mecca.[146] He declared an amnesty for past offences, except for ten men and women who had mocked and made fun of him in songs and verses. Some of these were later pardoned.[147] Most Meccans converted to Islam, and Muhammad subsequently destroyed all of the statues of Arabian gods in and around the Kaaba, without any exception.[148][149] The Qur'an discusses the conquest of Mecca in verses Qur'an 110:1-110:3. [66]

Conquest of Arabia

Soon after the conquest of Mecca, Muhammad was alarmed by a military threat from the confederate tribes of Hawazin who were collecting an army twice the size of Muhammad's. Hawzain were old enemies of Meccans. They were joined by the tribe of Thaqif inhabiting in the city of Ta'if who had adopted an anti-Meccan policy due to the decline of the prestige of Meccans. [150] Muhammad defeated the Hawzain and Thaqif in the battle of Hunayn. [18]

In the same year, Muhammad made the expedition of Tabuk against northern Arabia because of their previous defeat at the Battle of Mu'tah as well as the reports of the hostile attitude adopted against Muslims. Although Muhammad did not make contact with hostile forces at Tabuk, but he received the submission of some of the local chiefs of the region.[18] [151] A year after the battle of Tabuk, the tribe of Thaqif inhabiting in the city of Ta'if sent emissaries to Medina to surrender to Muhammad and adopt Islam. Many bedouins submitted to Muhammad in order to be safe against his attacks and to benefit from the booties of the wars.[18] The bediouns however were alien to the system of Islam and wanted to maintain their independence, their established code of virtue and their ancestral traditions. Muhammad, thus required of them a military and political agreement according to which they "acknowledge the suzeranity of Medina, to refrain from attack on the Muslims and their allies, and to pay the Zakat, the Muslim religous levy." [152]

The Farewell Pilgrimage

At the end of the tenth year after the migration to Medina, Muhammad carried through his first truly Islamic pilgrimage thereby teaching his followers the regulations of the various ceremonies of the annual Great Pilgrimage (hajj). On this incident, he delivered the Qur'anic verse: “Today I have perfected your religion, and completed my favours for you and chosen Islam as a religion for you.”(Qur'an 5:3). [18]

Death

A few month after the farewell pilgrimage, Muhammad fell ill and suffered for several days with head pain and weakness. He succumbed on Monday, June 8, 632, in the city of Medina. He is buried in his tomb (which previously was in his wife Aisha's house) which is now housed within Mosque of the Prophet in Medina.[153][18]

Marriages and children

Muhammad's life is traditionally defined into two epochs: pre-hijra (emigration) in Mecca, a city in northern Arabia, from the year 570 to 622, and post-hijra in Medina, from 622 until his death in 632. Muhammad is said to have had thirteen wives or concubines (there are differing accounts on the status of some of them as wife or concubine [154])[155] All but two of his marriages were contracted after the migration to Medina.

At the age of 25, Muhammad married Khadijah. The marriage lasted for 25 years[156] and is described as "long" and "happy". Muhammad relied upon Khadija in many ways[157][158] and did not enter into marriage with another woman during this marriage. After her death, friends of Muhammad advised him to marry again, but he was reluctant to do so.[158][157] It was suggested to Muhammad by Khawla bint Hakim, that he should marry Sawda bint Zama, a Muslim widow, or Aisha. Muhammad is said to have asked her to arrange for him to marry both. [159] Later, Muhammad married additional wives nine of whom survived him.[155] Aisha, who became Muhammad's favourite wife of his later years, was six years old when he married her and nine when he consumated the marriage. Young as she was she survived him by many decades, and was instrumental in helping to bring together the scattered sayings of Muhammad that would become the Qur'an.

In Arabian culture, marriage was generally contracted in accordance with the larger needs of the tribe and was based on the need to form alliances within the tribe and with other tribes. Virginity at the time of marriage was emphasized as a tribal honor.[160] Watt states that all of Muhammad's marriages had the political aspect of strengthening friendly relationships and were based on the Arabian custom. [161] Esposito points out that some of Muhammad's marriages were aimed at providing a livelihood for widows.[162] F.E. Peters says that it is hard to make generalizations about Muhammad's marriages: many of them were political, some compassionate, and some perhaps affairs of heart.[163]

Muhammad is said to have done his own household chores, helped out with the housework, such preparing food, sewing clothes, and repairing shoes. Muhammad is said to had accustomed his wives to dialogue; he listened to their advice, and the wives debated and even argued with him.[164][165]

Khadijah is said to have borne Muhammad four daughters (Ruqayyah bint Muhammad,Umm Kulthum bint Muhammad,Zainab bint Muhammad,Fatima Zahra) and two sons (Abd-Allah ibn Muhammad and Qasim ibn Muhammad), though all except two of his daughters, Fatima and Zaynab died before him.[166] Some Shia scholars however hold that Fatimah was Muhammad's only daughter. [167] Maria al-Qibtiyya bore him a son named Ibrahim ibn Muhammad, but the child died when he was two years old.[166]

Companions

The term Sahaba (companion) refers to anyone who meets three criteria: to be a contemporary of Muhammad, to have heard Muhammad speak on at least one occasion, and to be a convert to Islam. Companions are considered the ultimate sources for the oral traditions, or hadith, on which much of Muslim law and practice are based. The following are a few examples in alphabetic order:

|

|

|

|

Muhammad the reformer

According to William Montgomery Watt, for Muhammad, religion was not a private and individual matter but rather “the total response of his personality to the total situation in which he found himself. He was responding [not only]… to the religious and intellectual aspects of the situation but also to the economic, social, and political pressures to which contemporary Mecca was subject."[168]

Bernard Lewis says that there are two important political traditions in Islam — one that views Muhammad as a statesman in Medina, and another that views him as a rebel in Mecca. He sees Islam itself as a type of revolution that greatly changed the societies into which the new religion was brought.[169]

Historians generally agree that Islamic social reforms in areas such as social security, family structure, slavery and the rights of women and children improved on what was present in existing Arab society.[169][170] For example, according to Lewis, Islam "from the first denounced aristocratic privilege, rejected hierarchy, and adopted a formula of the career open to the talents"[169]

Muhammad's message transformed the society and moral order of life in the Arabian Peninsula through reorientation of society as regards to identity, world view, and the hierarchy of values.[171]

Economic reforms addressed the plight of the poor, which was becoming an issue in pre-Islamic Mecca.[172] The Qur'an requires payment of an alms tax (zakat) for the benefit of the poor,[173] and as Muhammad's position grew in power he demanded that those tribes who wanted to ally with him implement the zakat in particular.[174]

Miracles in the Muslim biographies

According to historian Denis Gril, the Qur'an does not overtly describe Muhammad performing miracles, and the supreme miracle of Muhammad is finally identified with the Qur’an itself. [175] However, Muslim tradition credits Muhammad with several supernatural events.[176] For example, many Muslim commentators and some western scholars have interpreted the Surah 54:1-2 to refer to Muhammad splitting the Moon in view of the Quraysh when they had begun to persecute his followers.[175][177] This tradition has inspired many Muslim poets, especially in India.[18] In order to defend the possibility of miracles and God's omnipotence against the encroachment of the independent secondary causes, medieval Muslim theologians rejected the idea of cause and effect in essence, but accepted it as something that facilitates humankind's investigation and comprehension of natural processes. They argued that the nature was composed of uniform atoms that were "re-created" at every instant by God. Thus if the soil was to fall, God would have to create and re-create the accident of heaviness for as long as the soil was to fall. For Muslim theologians, the laws of nature were only the customary sequence of apparent causes: customs of God.[178]

Modern Muslim biographies of Muhammad more often portray him as a progressive social and political reformer, successful military leader and model of human virtue.[179] According to Carl Ernst, Muslims began to de-emphasize superhuman views of Muhammad following the growth of scientific rationalism in Muslim countries.[180] Daniel Brown adds that Muslims of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, faced with social and political turmoil and the challenge of reforming Islamic law, began looking to Muhammad's life for examples which might more practically address these problems.[179]

Traditional views of Muhammad

Muslims have traditionally expressed love and veneration for Muhammad. Stories of Muhammad's life, his intercession and of his miracles (particularly "Splitting of the moon") have permeated popular Muslim thought and poetry. The Qur'an refers to Muhammad as "a mercy (rahmat) to the worlds" (Qur'an 21:107).[18] The association of rain with rahmat (mercy) in Oriental countries has led to imagination of Muhammad as a rain cloud dispensing blessing and stretching over lands, reviving the dead hearts, just as rain revives the seemingly dead earth (see for example the Sindhi poem of Shah ʿAbd al-Latif).[18] The story of ascension of Muhammad to heaven (mi'radj) is described in much details by poems in Turkey, India, Africa and other countries. The folk traditions contain miracles attributed to Muhammad not mentioned in the Qur'an (such as trees bowing before Muhammad, or a cloud protecting him from the sun).[18]

Muslims, especially Sufi Muslims, regard Muhammad as God's last messenger, and al-insan al-kamil, meaning, the "perfect man".[182] There are legends telling of how the whole world was filled with light at Muhammad's birth.[18]

Seal of the prophets

Muslims believe Muhammad to be the last in a line of prophets of God (Arabic Allah) and regard his mission as one of restoring the original monotheistic faith of Adam, Abraham and other prophets of Islam that had become altered by man over time.[17][18][10]

The Qur'an specifically refers to Muhammad as the "Seal of the Prophets", which is taken by most Muslims to believe him to be the last of the prophets.[183][184][185][25] Welch however holds that this Muslim belief is most likely a later interpretation of the Seal of the Prophets.[18] Carl Ernst considers this phrase to mean that Muhammad's "imprint on history is as final as a wax seal on a letter".[25] Wilferd Madelung states that the meaning of this term is not certain.[186]

Depictions of Muhammad

Islam forbids visual depictions of Muhammad.[188] That strict taboo is honored today by almost all Muslims.[189] The taboo is stronger in Sunni Islam (representing 85–90% of the world’s Muslim population) than Shia (10–15%).[22]

Figurative art of Muhammad was a significant part of late medieval Islamic art; however, it was generally limited to secular contexts and to the elite classes who could afford fine art.[21] Depictions of Muhammad were common during the Ottoman Empire, when the taboo on portraying him was less strong, although his face was often left blank.[22]

Muslim veneration of Muhammad

It is traditional for Muslims to illustrate and express love and veneration for Muhammad. Muhammad's birthday is celebrated as a major feast throughout the Islamic world, excluding the Wahhabi-dominated Saudi Arabia where these public celebrations are discouraged. In these celebrations, Muslims remember the miracles associated with Muhammad's life, "repeat the Qur'anic dictum that Muhammad was sent as 'mercy unto all the worlds', ask for his intercession on the Day of Judgment, hoping to assemble that day under the green 'flag of praise' carried by him." [190]

Muslim experience Muhammad as a living reality believing in his ongoing relation with human beings as well as animals and plants. Seyyed Hossein Nasr states: [190]

The benediction upon the Prophet punctuates daily Muslim life, and traditional Islamic life reminds one at every turn of his ubiquitous presence. He even plays a major role in dreams. There are many prayers recited in order to be able to have a dream of the Prophet, who promised that the Devil could never appear in a dream in the form of Muhammad. Not only for saints and mystics but also for many ordinary pious people, a simple dream of the Prophet has been able to transform a whole human life. One might say that the reality of the Prophet penetrates the life of Muslims on every level, from the external existence of the individual and of Islamic society as a whole to the life of the psyche and the soul and finally to the life of the spirit.

When Muslims say or write the name of Muhammad or any other Muslim prophet, they usually follow it with Peace be upon him or its Arabic equivalent, sallalahu alayhi wasallam,[191] and for Shias this is extended to Peace be upon him and his descendants. In English this is often abbreviated to "(pbuh)", "(saw)" and "pbuh&hd" for Shias, or even just simply as "p".

Christian and Western views of Muhammad

While Muslim writers have tended to speak highly of Muhammad, Western tradition has at times been critical of him.[192][193]

Popular image of Muhammad in medieval times

In the 12th century, Chansons de geste that mentioned Muhammad presented him as an idol to whom Muslims prayed for aid in battle.[18][194] Some medieval Christians said he had died in 666, alluding to the number of the beast, instead of 632;[195] others changed his name from Muhammad to Mahound, the "devil incarnate".[196] Bernard Lewis writes "The development of the concept of Mahound started with considering Muhammad as a kind of demon or false god worshipped with Apollyon and Termangant in an unholy trinity."[197] To discredit Islam, Muhammad was represented as an idol or one of the heathen gods during the first and second Crusade.[18]

Later medieval representations

From the middle of the 13th century, mentions of Muhammad in vernacular chivalric romance literature begin to appear. A poem represents Muhammad as "someone in bondage. Through his cleverly contrived marriage to the widow of his former master, he not only attains his freedom and wealth but also knows how to cover up his epileptic attacks as phenomena accompanying visitations of angels and to pose as a new messenger of God's will through deceitful machinations."[18] From this period is Scala Mahomete, a translation of an Arabic text, largely without Christian evaluations.[18] In a polemical tone, Livre dou Tresor represents Muhammad as a former monk and cardinal.[18] Dante's The Divine Comedy (Canto XXVIII), puts Muhammad, together with Ali, in Hell "among the sowers of discord and the schismatics, being lacerated by devils again and again."[18]

Early modern times

After the reformation, Muhammad was no longer viewed as a god or idol, but as a cunning, ambitious, and self-seeking impostor.[197][18]

Guillaume Postel was among the first to present a more positive view of Muhammad.[18] Boulainvilliers described Muhammad as a gifted political leader and a just lawmaker.[18] Leibniz praised Muhammad because "he did not deviate from the natural religion".[18]

Modern times

Friedrich Bodenstedt (1851) described Muhammad as "an ominous destroyer and a prophet of murder."[18]

According to Watt and Richard Bell, recent writers have generally dismissed the idea that Muhammad deliberately deceived his followers, arguing that Muhammad “was absolutely sincere and acted in complete good faith”.[198] Watt says that sincerity does not directly imply correctness: In contemporary terms, Muhammad might have mistaken for divine revelation his own unconscious.[199] Although Muhammad's image in the west is much less unfavorable than in the past, prejudicial folk beliefs remain.[200]

Watt and Lewis argue that viewing Muhammad as a self-seeking imposter makes it impossible to understand the development of Islam.[201][202] Welch holds that Muhammad was able to be so influential and successful because of his firm belief in his vocation.[18] Muhammad’s readiness to endure hardship for his cause when there seemed to be no rational basis for hope shows his sincerity.[203]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints considers Muhammad, along with Confucius, the Reformers, as well as philosophers including Socrates, Plato, and others, to have received a portion of God´s light and that moral truths were given to them to enlighten nations and bring a higher level of understanding to individuals.[204]

Other religious traditions in regard to Muhammad

- The Druze, who accept most but not all Qur'anic revelations, also consider him a prophet.

- Bahá'ís venerate Muhammad as one of a number of prophets or "Manifestations of God", but consider his teachings to have been superseded by those of Bahá'u'lláh.

See also

Notes

- ^ Muhittin Serin: Hattat Aziz Efendi, Istanbul (1988, 1999), ISBN 9-7576-6303-4, OCLC 51718704

- ^ Unicode has a special "Muhammad" ligature at U+FDF4 ﷴ

- ^ for the Arabic pronunciation.

- ^ Variants of Muhammad's name in French: "Mahon, Mahomés, Mahun, Mahum, Mahumet"; in German: "Machmet"; and in Old Icelandic: "Maúmet" cf Muhammad, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ Welch, noting the frequency of Muhammad being called as "Al-Amin"(Arabic: الأمين ), a common Arab name, suggests the possibility of "Al-Amin" being Muhammad's given name as it is a masculine form from the same root as his mother's name, A'mina. cf. "Muhammad", Encyclopedia of Islam Online; The sources frequently say that he, in his youth, was called by the nickname "Al-Amin" meaning "Honest, Truthful" cf. Ernst (2004), p. 85.

- ^ Elizabeth Goldman (1995). Believers: spiritual leaders of the world. Oxford University Press. p. 63.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1977) writes that "It is appropriate to use the word 'God' rather than the transliteration 'Allah'; cf. p. 32.

- ^ Esposito (1998), p. 12.

- ^ Esposito (2002b), pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c F. E. Peters (2003), p. 9.

- ^ Alphonse de Lamartine (1854), Historie de la Turquie, Paris, p. 280:

"Philosophe, orateur, apôtre, législateur, guerrier, conquérant d'idées, restaurateur de dogmes, d'un culte sans images, fondateur de vingt empires terrestres et d'un empire spirituel, voilà Mahomet!"

- ^ a b c d e f Islam, S. A. Nigosian, p. 6 , Indiana University Press Cite error: The named reference "Nigosian6" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, Oxford University Press, p.xi

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of World History (1998), p. 452

- ^ The word "islām" derives from the triconsonantal Arabic root sīn-lām-mīm, which carries the basic meaning of safety and peace. The verbal noun "islām" is formed from the verb aslama, a derivation of this root which means to accept, surrender, or submit; thus, 'Islam' effectively means submission to and acceptance of God. See: Islam#Etymology and meaning

- ^ 'Islam' is always referred to in the Qur'an as a 'dīn', a word that means 'way' or 'path' in Arabic, but is usually translated in English as 'religion' for the sake of convenience

- ^ a b Esposito (1998), p. 12; (1999) p. 25; (2002) pp. 4–5 Cite error: The named reference "EspositoI" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw "Muhammad", Encyclopedia of Islam Online Cite error: The named reference "EoI-Muhammad" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ After Muhammad's migration to Yathrib, the city came to be known as Madina al-Nabi, lit. 'City of the Prophet'; hence, the name Medina

- ^ The term Qur'an was first used in the Qur'an itself. There are two different theories about this term and its formation that are discussed in Quran#Etymology cf. "Qur'an", Encyclopedia of Islam Online.

- ^ a b "Islamic Figurative Art and Depictions of Muhammad". Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ^ a b c Browne, Anthony (2006-02-04). "Portraying prophet from Persian art to South Park". The Times. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dan McCormack. "Online Etymology Dictionary". Douglas Harper. Retrieved August 14.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ There are reports of other Arabs before Muhammad who were named "Muhammad" (e.g. Ibn Sa'd). Welch (cf. "Muhammad", "Encyclopedia of Islam") accepts usage of the name "Muhammad" among Arabs but also points out that these reports have a tendentious nature. For example Ibn Sa'd's report has the heading, "Account of those who were named Muhammad in the days of the jahilliya Pre-Islamic Arabia in the hope of being called to prophethood which had been predicted."

- ^ a b c Ernst (2004), p. 80

- ^ a b Reeves (2003), pp. 6–7

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 32

- ^ F. E. Peters, The Quest for Historical Muhammad, International Journal of Middle East Studies (1991) pp. 291–315.

- ^ Donner (1998), p. 132

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, Oxford University Press, p.xii

- ^ Lewis (1993), pp. 33–34

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, Oxford University Press, p.xv

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, Oxford University Press, p. xi

- ^ Loyal Rue, Religion Is Not about God: How Spiritual Traditions Nurture Our Biological,2005, p.224

- ^ a b c d e William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, Oxford University Press, p.1-2

- ^ John Esposito, Islam, Expanded edition, Oxford University Press, p.4-5

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, 16

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, 17-18

- ^ Fazlur Rahman, Islam, Chicago University Press, p.12-13

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, 19

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, p.19

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Mecca, p.19-20

- ^ Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum: The Lineage and Family of Muhammad by Saifur Rahman al-Mubarakpuri

- ^ See also [Quran 43:31] cited in EoI; Muhammad

- ^ a b c William Montgomery Watt (1974), p. 7.

- ^ "By Mufti Taqi Usmani".

- ^ Allameh Tabatabaei, A glance at the life of the holy prophet of Islam, p. 20

- ^ Josef W. Meri (2005), p. 525

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, "Halimah bint Abi Dhuayb", Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Amina, Encyclopaedia of Islam

- ^ a b William Montgomery Watt (1974), p. 8.

- ^ a b Chris Charles Park (1994), p. 266.

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad, Prophet and Statesman, p. 8.

- ^ a b Berkshire Encyclopedia of World History (2005), v.3, p. 1025

- ^ Esposito (1998), p. 6

- ^ FE Peters (2003), p. 54.

- ^ Jonathan M. Bloom, Sheila S. Blair (2002), p. 28–29

- ^ Brown (2003), pp. 72–73

- ^ Rodinson, p. 71.

- ^ Brown (2003), pp. 73–74

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 31.

- ^ Ali, Wijdan. "From the Literal to the Spiritual: The Development of Prophet Muhammad's Portrayal from 13th century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th century Ottoman Art". In Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art, eds. M. Kiel, N. Landman, and H. Theunissen. No. 7, 1–24. Utrecht, The Netherlands, August 23–28, 1999, p. 7

- ^ a b William Montgomery Watt (1953), p. 86

- ^ a b c The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 36.

- ^ Francis Edwards Peters,Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, SUNY Press, p.168

- ^ a b c Uri Rubin, Quraysh, Encyclopaedia of the Qur'an

- ^ Francis Edwards Peters,Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, SUNY Press, p.169

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 37

- ^ Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Slaves and Slavery

- ^ Bilal b. Rabah, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ Watt (1964) p. 76.

- ^ Peters (1999) p. 172.

- ^ Some early Islamic histories recount that as Muhammad was reciting Sūra Al-Najm (Q.53), as revealed to him by the angel Gabriel, Satan tempted him to utter the following lines after verses 19 and 20: "Have you thought of Allāt and al-'Uzzā and Manāt the third, the other; These are the exalted Gharaniq, whose intercession is hoped for." (Allāt, al-'Uzzā and Manāt were three goddesses worshiped by the Meccans). cf Ibn Ishaq, A. Guillaume p. 166.

- ^ EoQ, Satanic Verses, Shahab Ahmed

- ^ Francis E. Peters, The Monotheists: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Conflict and Competition, p. 96

- ^ a b c Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʻism, Yale University Press, p. 4

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Islam and the Muslim World (2003), p. 482

- ^ Sells, Michael. Ascension, Encyclopedia of the Quran.

- ^ a b c d The Cambridge History of Islam (1977), p. 39

- ^ a b Esposito (1998), p. 17.

- ^ Moojan Momen, An Introduction to Shi'i Islam: The History and Doctrines of Twelver Shiʻism, Yale University Press, p. 5

- ^ Fazlur Rahman, Islam, Chicago University Press, p. 21

- ^ William Montgomery Watt, Muhammad in Medina, pp. 175, 177.

- ^ Norman Stillman, Yahud, Encyclopedia of Islam

- ^ Lewis, "The Arabs in History," 2003, p. 44.

- ^ Francis E. Peters, Muhammad and the Origins of Islam, p. 211.