Mug shot

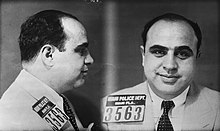

A mug shot or mugshot (an informal term for police photograph or booking photograph) is a photographic portrait of a person from the shoulders up, typically taken after a person is placed under arrest.[1][2] The primary purpose of the mug shot is to allow law enforcement to have a photographic record of an arrested individual to allow for identification by victims, the public and investigators. However, in the United States, entrepreneurs have recently begun to monetize these public records via the mug shot publishing industry.

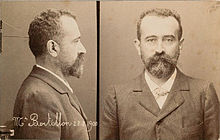

Photographing of criminals began in the 1840s only a few years after the invention of photography, but it was not until 1888 that French police officer Alphonse Bertillon standardized the process.

Etymology

[edit]"Mug" is an English slang term for "face", dating from the 18th century.[3] Mug shot can more loosely mean any small picture of a face used for any reason.[4]

Description

[edit]A typical mug shot is two-part, with one side-view photo, and one front-view. The background is usually plain to avoid distraction from the head. Mug shots may be compiled into a mug book in order to determine the identity of a criminal. In high-profile cases, mug shots may also be published in the mass media.

History

[edit]

The earliest photos of prisoners taken for use by law enforcement may have been taken in Belgium in 1843 and 1844.[5] In Australia, police in Sydney were photographing criminals by 1846.[6] In the United Kingdom, police in Liverpool[7] and Birmingham[8] were doing so by 1848. By 1853, the Philadelphia Police Department had a gallery where daguerreotypes of criminals were displayed.[9] and the New York Police Department had the same by 1857.[5]

The Pinkerton National Detective Agency began using these on wanted posters in the United States. By the 1870s the agency had amassed the largest collection of mug shots in the US.[10]

The paired arrangement may have been inspired by the 1865 prison portraits taken by Alexander Gardner of accused conspirators in the Lincoln assassination trial, though Gardner's photographs were full-body portraits with only the heads turned for the profile shots.

After the defeat of the Paris Commune in 1871, the Prefecture of Police of Paris hired a photographer, Eugène Appert, to take portraits of convicted prisoners. In 1888, Alphonse Bertillon invented the modern mug shot featuring full face and profile views, standardizing the lighting and angles. This system was soon adopted throughout Europe, and in the United States and Russia.[11]

The arrested person is sometimes required to hold a placard with name, date of birth, booking ID, weight, and other relevant information on it. With digital photography, the digital photograph is linked to a database record concerning the arrest.[citation needed] In some jurisdictions, mug shots are not legally required to be taken, mostly in the cases of high-profile individuals already known to a wider public.[12]

Use in wanted posters

[edit]

Mug shots have often been incorporated into wanted posters, including those for the FBI Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list.

Online mug shot publishing

[edit]In the US in the early 21st century an online industry developed around the publication and removal of mug shots from internet websites.

Prejudicial nature

[edit]The US legal system has long held that mug shots can have a negative effect on juries. The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit held, "The double-shot picture, with front and profile shots alongside each other, is so familiar, from 'wanted' posters in the post office, motion pictures and television, that the inference that the person involved has a criminal record, or has at least been in trouble with the police, is natural, perhaps automatic."[13]

According to the Handbook of Massachusetts Evidence, "Because of the risk of prejudice to the defendant inherent in the admission of photographs of the 'mug shot' variety, judges and prosecutors are required to 'use reasonable means to avoid calling the jury's attention to the source of such photographs used to identify the defendant.'" (p. 617) Elsewhere, it cites a ruling in Commonwealth v. Martin that "admission of a defendant's mug shot is 'laden for characterizing the defendant as a careerist in crime'".

Other states have similar rules. For example, Illinois specifies that all mug shots and booking information should be redacted.[14]

Mug book

[edit]

A mug book is a collection of photographs of criminals, typically in mug shots taken at the time of an arrest. A mug book is used by an eyewitness to a crime, with the assistance of law enforcement, in an effort to identify the perpetrator.[15][16] Research has shown that grouped photos result in fewer false-positives than individually displaying each photo.[17]

Mug book also has a meaning in genealogy and history, referring to local biographical histories published in the US in the late 19th century.[18][19][20]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Mugshot". Dictionary.cambridge.org. 29 October 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ Michael H. Graham (2003). Handbook of Illinois Evidence. Aspen Publishers. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-7355-4499-4.

- ^ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ a b Kennedy, Randy (15 September 2006). "Grifters and Goons, Framed (and Matted)". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-768757923/view?sectionId=nla.obj-827987616&searchTerm=Whaling&partId=nla.obj-768758535#page/n2/mode/1up/search/Whaling "A Cracksman," The Will O'the Wisp, 1 (2) Saturday 11 July 1846, p.3

- ^ Norfolk, Lawrence (17 September 2006). "A history of the twentieth century in mugshots". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ Papi, Giacomo (2006). Under Arrest: A History of the Twentieth Century in Mugshots. London: Granta Books. pp. 144, 163, 165. ISBN 9781862078925.

- ^ The Illustrated News, 15 March 1853, P. 186

- ^ Julie K. Petersen (2007). Understanding Surveillance Technologies: Spy Devices, Privacy, History, & Applications. Auerbach Publications. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8493-8319-9.

- ^ Pellicer, Raymond (2010). Mug Shots: An Archive of the Famous, Infamous and Most Wanted. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 9780810996120.

- ^ "Trump Did Not Have a Mugshot Taken During His Arrest". CBS News. 4 April 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Barnes v. United States, 124 U.S.App.D.C. 318, 365 F.2d 509, 510--11 (1966)

- ^ Graham, Michael (2004). "401.8". Cleary and Graham's Handbook of Illinois Evidence. Aspen Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-7355-4499-4.

Where admitted, to the extent possible, the mug shots should be taped over or cut to delete all reference to booking information and be undated. The photographs should not be referred to as either \"mug shots\" or \"booking photographs.\"\

- ^ Thetford, Robert T., Mug Shots, Mug Books, and Photo Spreads, Institute for Criminal Justice Education, Inc (ICJE) Archived 29 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ http://www.ncjrs.gov/nij/eyewitness/identification.html NIJ training manual on the use of mug books and composites with eyewitnesses

- ^ Stewart, Heather A.; Hunter A. McAllister (2001). "One-At-A-Time Versus Grouped Presentation of Mug Book Pictures: Some Surprising Results". Journal of Applied Psychology. 86 (6): 1300–1305. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.86.6.1300. ISSN 0021-9010. PMID 11768071.

- ^ "Frevert, Rhonda, Tales From The Vault: Mug Books, Common Place Vol. 3 No. 1 (October 2002)". Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- ^ http://www.ancestry.com/learn/library/article.aspx?article=2244 Collected Biography, Ancestry Magazine Vol. 13 No. 4 (July/August 1995)

- ^ Conzen, Michael P., "Local Migration Systems in Nineteenth-Century Iowa", Geographical Review, Vol. 64 No. 3 (July 1974), p. 341