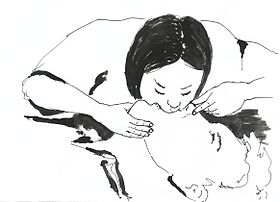

Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation

| Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation | |

|---|---|

Mouth-to-mouth insufflation | |

| ICD-9-CM | 93.93 |

| MeSH | D012121 |

Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, a form of artificial ventilation, is the act of assisting or stimulating respiration in which a rescuer presses their mouth against that of the victim and blows air into the person's lungs.[1][2] Artificial respiration takes many forms, but generally entails providing air for a person who is not breathing or is not making sufficient respiratory effort on their own.[3] It is used on a patient with a beating heart or as part of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to achieve the internal respiration.

Pulmonary ventilation (and hence external respiration) is achieved through manual insufflation of the lungs either by the rescuer blowing into the patient's lungs, or by using a mechanical device to do so. This method of insufflation has been proved more effective than methods which involve mechanical manipulation of the patient's chest or arms, such as the Silvester method.[4] It is also known as expired air resuscitation (EAR), expired air ventilation (EAV), rescue breathing, or colloquially the kiss of life. It was introduced as a life-saving measure in 1950.[5]

Mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is a part of most protocols for performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)[6][7] making it an essential skill for first aid. In some situations, mouth-to-mouth resuscitation is also performed separately, for instance in near-drowning and opiate overdoses. The performance of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation on its own is now limited in most protocols to health professionals, whereas lay first-aiders are advised to undertake full CPR in any case where the patient is not breathing sufficiently.

History

[edit]In 1773, English physician William Hawes (1736–1808) began publicising the power of artificial respiration to resuscitate people who superficially appeared to have drowned. For a year he paid a reward out of his own pocket to any one bringing him a body rescued from the water within a reasonable time of immersion. Thomas Cogan, another English physician, who had become interested in the same subject during a stay at Amsterdam, where in 1767 a society for preservation of life from accidents in water was instituted, joined Hawes in his crusade. In the summer of 1774 Hawes and Cogan each brought fifteen friends to a meeting at the Chapter Coffee-house, St Paul's Churchyard, where they founded the Royal Humane Society as a campaigning group for first aid and resuscitation.[8]

Gradually, branches of the Royal Humane Society were set up in other parts of the country, mainly in ports and coastal towns where the risk of drowning was high and by the end of the 19th century the society had upwards of 280 depots throughout the UK, supplied with life-saving apparatus. The earliest of these depots was the Receiving House in Hyde Park, on the north bank of the Serpentine, which was built in 1794 on a site granted by George III. Hyde Park was chosen because tens of thousands of people swam in the Serpentine in the summer and ice-skated in the winter. Boats and boatmen were kept to render aid to bathers, and in the winter ice-men were sent round to the different skating grounds in and around London.

The society distributed money-rewards, medals, clasps and testimonials, to those who saved or attempted to save drowning people. It further recognized "all cases of exceptional bravery in rescuing or attempting to rescue persons from asphyxia in mines, wells, blasting furnaces, or in sewers where foul gas may endanger life."[8]

Insufflations

[edit]

Insufflation, also known as 'rescue breaths' or 'ventilations', is the act of mechanically forcing air into a patient's respiratory system. This can be achieved via a number of methods, which will depend on the situation and equipment available. All methods require good airway management to perform, which ensures that the method is effective. These methods include:[citation needed]

- Mouth-to-mouth - This involves the rescuer making a seal between his or her mouth and the patient's mouth and 'blowing', to pass air into the patient's body

- Mouth-to-nose - In some instances, the rescuer may need or wish to form a seal with the patient's nose. Typical reasons for this include maxillofacial injuries, performing the procedure in water or the remains of vomit in the mouth

- Mouth-to-face - Used on both animal muzzles and infants under 2, as this forms the most effective seal on both the mouth and nostrils

- Mouth-to-mask – Most organisations recommend the use of some sort of barrier between rescuer and patient to reduce cross infection risk. One popular type is the 'pocket mask'. This may be able to provide higher tidal volumes than a Bag Valve Mask.[9]

Adjuncts to insufflation

[edit]

Most training organisations recommend that in any of the methods involving mouth-to-patient, that a protective barrier is used, to minimise the possibility of cross infection (in either direction).[10]

Barriers available include pocket masks and keyring-sized face shields. These barriers are an example of personal protective equipment to guard the face against splashing, spraying or splattering of blood or other potentially infectious materials.[11]

These barriers should provide a one-way filter valve which lets the air from the rescuer deliver to the patient while any substances from the patient (e.g. vomit, blood) cannot reach the rescuer. Many adjuncts are single use, though if they are multi use, after use of the adjunct, the mask must be cleaned and autoclaved and the filter replaced. It is very important for the mask to be replaced or cleaned because it can act as a transporter of various diseases.

The CPR mask is the preferred method of ventilating a patient when only one rescuer is available. Many feature 18 mm (0.71 in) inlets to support supplemental oxygen, which increases the oxygen being delivered from the approximate 17% available in the expired air of the rescuer to around 40-50%.[12]

Efficiency of mouth-to-patient insufflation

[edit]Normal atmospheric air contains approximately 21% oxygen when inhaled. After gaseous exchange has taken place in the lungs, with waste products (notably carbon dioxide) moved from the bloodstream to the lungs, the air being exhaled by humans normally contains around 17% oxygen. This means that the human body utilises only around 19% of the oxygen inhaled, leaving over 80% of the oxygen available in the exhalatory breath.[13]

This means that there is more than enough residual oxygen to be used in the lungs of the patient, which then enters the blood.

Oxygen

[edit]The efficiency of artificial respiration can be greatly increased by the simultaneous use of oxygen therapy. The amount of oxygen available to the patient in mouth-to-mouth is around 16%. If this is done through a pocket mask with an oxygen flow, this increases to 40% oxygen. If either a bag valve mask or a mechanical ventilator is used with an oxygen supply, this rises to 99% oxygen. The greater the oxygen concentration, the more efficient the gaseous exchange will be in the lungs.[14]

See also

[edit]- Mechanical ventilation - using mechanical devices to assist or replace spontaneous breathing

- Medical emergency

References

[edit]- ^ "Definition of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ Tortora, Gerard J; Derrickson, Bryan (2006). Principles of Anatomy and Physiology. John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- ^ "Artificial Respiration". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 14 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ "Artificial Respiration". Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2007. Archived from the original on 2004-01-04. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ Stathis Avramidis, Facts, Legends and Myths on the Evolution of Resuscitation, page 27

- ^ "Decisions about cardiopulmonary resuscitation model information leaflet". British Medical Association. July 2002. Archived from the original on 2007-07-05. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ "Overview of CPR". Circulation. 112 (24 sup). 2005. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.166552.

- ^ a b One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Humane Society, Royal". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Dworkin, Gerald M (Winter 1987). "Mouth-to-Mask rescue breathing and comparisons of personal resuscitation masks". Rescue Squad Quarterly. Archived from the original on 2007-06-02. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ "Emergency Cardiovascular Care Revisions for the professional rescuer" (DOC). American Red Cross. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ Verbeek, Jos; Ijaz, Sharea; Tikka, Christina; Ruotsalainen, Jani; Mäkelä, Erja; Neuvonen, Kaisa; Edmond, Michael; Sauni, Riitta; Kilinc Balci, FSelcen (April 2018). "303 Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff". Health Services Research. BMJ Publishing Group: A177.1–A177. doi:10.1136/oemed-2018-icohabstracts.500. hdl:1983/74503ffd-6d75-4f3d-bc60-9175e49b2331.

- ^ Handley, Anthony J.; Becker, Lance B.; Allen, Mervyn; Drenth, Ank van; Kramer, Efraim B.; Montgomery, William H. (15 April 1997). "Single-Rescuer Adult Basic Life Support". Circulation. 95 (8): 2174–2179. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.95.8.2174. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 9133531.

- ^ "Physical Intervention: Life Support (Rescue Breathing)". Archived from the original on 25 January 2006. Retrieved December 29, 2005.

- ^ Petersson, J.; Glenny, R. W. (25 July 2014). "Gas exchange and ventilation-perfusion relationships in the lung". European Respiratory Journal. 44 (4): 1023–1041. doi:10.1183/09031936.00037014. PMID 25063240.