Mount Ararat

| Mount Ararat | |

|---|---|

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 5,137 m (16,854 ft) See Elevation section |

| Prominence | 3,611 m (11,847 ft)[1] Ranked 48th |

| Isolation | 379.29 km (235.68 mi) |

| Listing | Country high point Ultra Volcanic Seven Second Summits |

| Coordinates | 39°42′07″N 44°17′54″E / 39.7019°N 44.2983°E[2] |

| Naming | |

| Native name | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Iğdır and Ağrı provinces, Turkey |

| Region | Eastern Anatolia Region |

| Parent range | Armenian Highlands |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Stratovolcano |

| Last eruption | July 2, 1840 |

| Climbing | |

| First ascent | 9 October [O.S. 27 September] 1829 Friedrich Parrot, Khachatur Abovian, two Russian soldiers, two Armenian villagers |

| Designations | |

|---|---|

IUCN Category II (National Park) | |

| Official name | Ağrı Dağı Milli Parkı |

| Designated | 1 November 2004[3] |

Mount Ararat[a] (/ˈærəræt/, ARR-ə-rat; Armenian: Արարատ, romanized: Ararat [ɑɾɑˈɾɑt] ⓘ) or Mount Ağrı (Turkish: Ağrı Dağı; Kurdish: Çiyayê Agirî)[4][5] is a snow-capped and dormant compound volcano in Eastern Turkey. It consists of two major volcanic cones: Greater Ararat and Little Ararat. Greater Ararat is the highest peak in Turkey; Little Ararat's elevation is 3,896 m (12,782 ft).[6] The Ararat massif is about 35 km (22 mi) wide at ground base.[7] The first recorded efforts to reach Ararat's summit were made in the Middle Ages, and Friedrich Parrot, Khachatur Abovian, and four others made the first recorded ascent in 1829.

In Europe, the mountain has been called by the name Ararat since the Middle Ages, as it began to be identified with "mountains of Ararat" described in the Bible as the resting-place of Noah's Ark, despite contention that Genesis 8:4 does not refer specifically to a Mount Ararat.

Although lying outside the borders of modern Armenia, the mountain is the principal national symbol of Armenia and has been considered a sacred mountain by Armenians. It has featured prominently in Armenian literature and art and is an icon for Armenian irredentism. It is depicted on the coat of arms of Armenia along with Noah's Ark.

Political borders

Mount Ararat forms a near-quadripoint between Turkey, Iran, Armenia, and the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan. Its summit is located some 16 km (10 mi) west of both the Iranian border and the border of the Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan, and 32 km (20 mi) south of the Armenian border. The Turkish-Armenian-Azerbaijani and Turkish-Iranian-Azerbaijani tripoints are some 8 km (5 mi) apart, separated by a narrow strip of Turkish territory containing the E99 road which enters Nakhchivan at 39°39′19″N 44°48′12″E / 39.6553°N 44.8034°E.

From the 16th century until 1828 the range was part of the Ottoman-Persian border; Great Ararat's summit and the northern slopes, along with the eastern slopes of Little Ararat were controlled by Persia. Following the 1826–28 Russo-Persian War and the Treaty of Turkmenchay, the Persian controlled territory was ceded to the Russian Empire. Little Ararat became the point where the Turkish, Persian, and Russian imperial frontiers converged.[8] The current international boundaries were formed throughout the 20th century. The mountain came under Turkish control during the 1920 Turkish–Armenian War.[9] It formally became part of Turkey according to the 1921 Treaty of Moscow and Treaty of Kars.[10] In the late 1920s, Turkey crossed the Iranian border and occupied the eastern flank of Lesser Ararat as part of its effort to quash the Kurdish Ararat rebellion,[11] during which the Kurdish rebels used the area as a safe haven against the Turkish state.[12] Iran eventually agreed to cede the area to Turkey in a territorial exchange.[11][13] The Iran-Turkey boundary skirts east of Lesser Ararat (or Little Ararat), the lower peak of the Ararat massif.

As of 2004[update] the mountain was open to climbers only with "military permission". The procedure to obtain the permission involves submitting a formal request to a Turkish embassy for a special "Ararat visa", and it is mandatory to hire an official guide from the Turkish Federation for Alpinism.

Names and etymology

Ararat

Ararat (Western Armenian: Ararad) is the Biblical Hebrew name (אררט ʾrrṭ)[14][b] cognate with Assyrian Urartu,[15] of a kingdom that existed in the Armenian Highlands in the 9th–6th centuries BC.[c] The mountain is known as Ararat in European languages,[19][20] however, none of the native peoples have traditionally referred to the mountain by that name.[21] This mountain was not called by the name Ararat until the Middle Ages; early Armenian historians considered the biblical Ararat to be in Corduene.[22][23] Ayrarat, the central province of the Greater Armenia, is believed to originate from the same name.[24]

Ağrı and Agirî

The Turkish name Mount Ağrı (Ağrı Dağı, [aːɾɯ da.ɯ]; Ottoman Turkish: آغـر طﺎﻍ, romanized: Āġır Ṭāġ, [aːɣæɾ taɣ]), has been known since the late Middle Ages.[25] Although the word "ağrı" literally translates to "pain" the current name is considered a derivative of the mountain's initial Turkish name "Ağır Dağ" which translates as "heavy mountain".[26][19][25][27][28] The 17th century explorer Evliya Çelebi referred to it as Ağrî in the Seyahatnâme. Despite the supposed meaning in Turkish Ağrı Dağı as "pain mountain" and Kurdish Çiyayê Agirî as "fiery mountain", some linguists underline a relationship between the mountain's name and a village on its slopes called Ağori that was decimated after a landslide in 1840. The exact meaning of these related names remains unknown.[29]

The Kurdish name of the mountain is Çiyayê Agirî[30][31] ([t͡ʃɪjaːˈje aːgɪˈriː]), which translates to "fiery mountain".[4] An alternative Kurdish name is Grîdax, which is composed of the word grî, presumably a corrupted version of the Kurdish girê, meaning hill, or Agirî, and dax, which is the Turkish dağ, meaning mountain.[32]

Masis

The traditional Armenian name is Masis (Մասիս [maˈsis]; sometimes Massis).[33][21] However, nowadays, the terms Masis and Ararat are both widely, often interchangeably, used in Armenian.[34][d] The folk etymology found in Movses Khorenatsi's History of Armenia derives the name from king Amasya, the great-grandson of the legendary Armenian patriarch Hayk, who is said to have called it after himself.[39][40]

Various scholarly etymologies have been proposed.[e] Anatoly Novoseltsev suggested that Masis derives from Middle Persian masist, "the largest".[25] According to Sargis Petrosyan the mas root in Masis means "mountain", cf. Proto-Indo-European *mņs-.[40] Armen Petrosyan suggested an origin from the Māšu (Mashu) mountain mentioned in the Epic of Gilgamesh, which sounded like Māsu in Assyrian.[44] The name meant "twin", referring to the twin peaks of the mountain. Erkuahi, a land mentioned in Urartian texts and identified with Mt. Ararat, could reflect the native Armenian form of this same name (compare to Armenian erku (երկու, "two")).[45]

Today, both Ararat and Masis are common male first names among Armenians.[46]

Other names

The traditional Persian name is کوه نوح ([ˈkuːhe ˈnuːh], Kūh-e Nūḥ),[8] literally the "mountain of Noah".[19][33]

In classical antiquity, particularly in Strabo's Geographica, the peaks of Ararat were known in ancient Greek as Ἄβος (Abos) and Νίβαρος (Nibaros).[f]

Geography

Mount Ararat is located in the Eastern Anatolia Region of Turkey, between the provinces of Ağrı and Iğdır, near the border with Iran, Armenia and Nakhchivan exclave of Azerbaijan, between the Aras and Murat rivers.[51] The Serdarbulak lava plateau, at 2600 meters of elevation, separates the peaks of Greater and Little Ararat.[52] There are Doğubayazıt Reeds on the western slopes of Mount Ararat.[53] Mount Ararat's summit is located some 16 km (10 mi) west of the Turkey-Iran border and 32 km (20 mi) south of the Turkey-Armenia border. The Ararat plain runs along its northwest to western side.

Elevation

Ararat is the third most prominent mountain in West Asia.

An elevation of 5,165 m (16,946 ft) for Mount Ararat is given by some encyclopedias and reference works such as Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary and Encyclopedia of World Geography.[54][55][56][57] However, a number of sources, such as the United States Geological Survey and numerous topographic maps indicate that the alternatively widespread figure of 5,137 m (16,854 ft) is probably more accurate.[58][59] The current elevation may be as low as 5,125 m (16,814 ft) due to the melting of its snow-covered ice cap.[60]

Summit ice cap

The ice cap on the summit of Mount Ararat has been shrinking since at least 1957. In the late 1950s, Blumenthal observed that there existed 11 outlet glaciers emerging from a summit snow mass that covered about 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi).[61] At that time, it was found that the present glaciers on the summit of Ararat extend as low as an elevation of 3,900 meters (12,800 ft) on the north-facing slope, and an elevation of 4,200 meters (13,800 ft) on its south-facing slope.[61] Using pre-existing aerial imagery and remote sensing data, Sarıkaya and others studied the extent of the ice cap on Mount Ararat between 1976 and 2011.[30][62] They discovered that this ice cap had shrunk to 8.0 km2 (3.1 sq mi) by 1976 and to 5.7 km2 (2.2 sq mi) by 2011. They calculated that between 1976 and 2011, the ice cap on top of Mount Ararat had lost 29% of its total area at an average rate of ice loss of 0.07 km2 (0.027 sq mi) per year over 35 years. This rate is consistent with the general rates of retreat of other Turkish summit glaciers and ice caps that have been documented by other studies.[62] According to a 2020 study by Yalcin, "if the glacial withdrawals continue with the same acceleration, the permanent glacier will likely turn into a temporary glacier by 2065."[63]

Blumenthal estimated that the snow line had been as low as 3,000 meters (9,800 ft) in elevation during the Late Pleistocene.[61] Such a snow line would have created an ice cap of 100 km2 (39 sq mi) in extent. However, he observed a lack of any clear evidence of prehistoric moraines other than those which were close to the 1958 glacier tongues. Blumenthal explained the absence of such moraines by the lack of confining ridges to control glaciers, insufficient debris load in the ice to form moraines, and their burial by later eruptions. Years later, Birman observed on the south-facing slopes a possible moraine that extends at least 300 meters (980 ft) in altitude below the base of the 1958 ice cap at an elevation of 4,200 meters (13,800 ft).[64] He also found two morainal deposits that were created by a Mount Ararat valley glacier of Pleistocene, possibly in the Last Glacial Period, downvalley from Lake Balık. The higher moraine lies at an altitude of about 2,200 meters (7,200 ft) and the lower moraine lies at an altitude of about 1,800 meters (5,900 ft). The lower moraine occurs about 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) downstream from Lake Balık. Both moraines are about 30 meters (98 ft) high. It is suspected that Lake Balık occupies a glacial basin.[64]

Geology

Mount Ararat is a polygenic, compound stratovolcano. Covering an area of 1,100 km2 (420 sq mi), it is the largest volcanic edifice within the region. Along its northwest–southeast trending long axis, Mount Ararat is about 45 kilometers (28 mi) long and is about 30 kilometers (19 mi) long along its short axis. It consists of about 1,150 km3 (280 cu mi) of dacitic and rhyolitic pyroclastic debris and dacitic, rhyolitic, and basaltic lavas.[6]

Mount Ararat consists of two distinct volcanic cones, Greater Ararat and Lesser Ararat (Little Ararat). The western volcanic cone, Greater Ararat, is a steep-sided volcanic cone that is larger and higher than the eastern volcanic cone. Greater Ararat is about 25 kilometers (16 mi) wide at the base and rises about 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) above the adjacent floors of the Iğdir and Doğubeyazıt basins. The eastern volcanic cone, Lesser Ararat, is 3,896 meters (12,782 ft) high and 15 kilometers (9.3 mi) across. These volcanic cones, which lie 13 kilometers (8.1 mi) apart, are separated by a wide north–south-trending crack. This crack is the surface expression of an extensional fault. Numerous parasitic cones and lava domes have been built by flank eruptions along this fault and on the flanks of both of the main volcanic cones.[6]

Mount Ararat lies within a complex, sinistral pull-apart basin that originally was a single, continuous depression. The growth of Mount Ararat partitioned this depression into two smaller basins, the Iğdir and Doğubeyazıt basins. This pull-apart basin is the result of strike-slip movement along two en-echelon fault segments, the Doğubeyazıt–Gürbulak and Iğdir Faults, of a sinistral strike–slip fault system. Tension between these faults not only formed the original pull-apart basin, but created a system of faults, exhibiting a horsetail splay pattern, that control the position of the principal volcanic eruption centers of Mount Ararat and the associated linear belt of parasitic volcanic cones. The strike-slip fault system within which Mount Ararat is located is the result of north–south convergence and tectonic compression between the Arabian Platform and Laurasia that continued after the Tethys Ocean closed during the Eocene epoch along the Bitlis–Zagros suture.[6][65][66]

Geological history

During the early Eocene and early Miocene, the collision of the Arabian platform with Laurasia closed and eliminated the Tethys Ocean from the area of what is now Anatolia. The closure of these masses of continental crust collapsed this ocean basin by middle Eocene and resulted in a progressive shallowing of the remnant seas, until the end of the early Miocene. Post-collisional tectonic convergence within the collision zone resulted in the total elimination of the remaining seas from East Anatolia at the end of early Miocene, crustal shortening and thickening across the collision zone, and uplift of the East Anatolian–Iranian plateau. Accompanying this uplift was extensive deformation by faulting and folding, which resulted in the creation of numerous local basins. The north–south compressional deformation continues today as evidenced by ongoing faulting, volcanism, and seismicity.[6][65][67]

Within Anatolia, regional volcanism started in the middle-late Miocene. During the late Miocene–Pliocene period, widespread volcanism blanketed the entire East Anatolian–Iranian plateau under thick volcanic rocks. This volcanic activity has continued uninterrupted until historical times. Apparently, it reached a climax during the latest Miocene–Pliocene, 6 to 3 Ma. During the Quaternary, the volcanism became restricted to a few local volcanoes such as Mount Ararat. These volcanoes are typically associated with north–south tensional fractures formed by the continuing north–south shortening deformation of Anatolia.[6]

In their detailed study and summary of the Quaternary volcanism of Anatolia, Yilmaz et al. recognized four phases to the construction of Mount Ararat from volcanic rocks exposed in glacial valleys deeply carved into its flanks.[6] First, they recognized a fissure eruption phase of Plinian-subPlinian fissure eruptions that deposited more than 700 meters (2,300 ft) of pyroclastic rocks and a few basaltic lava flows.

These volcanic rocks were erupted from approximately north northwest–south southeast-trending extensional faults and fissures prior to the development of Mount Ararat. Second, a cone-building phase began when the volcanic activity became localized at a point along a fissure. During this phase, the eruption of successive flows of lava up to 150 meters (490 ft) thick and pyroclastic flows of andesite and dacite composition and later eruption of basaltic lava flows, formed the Greater Ararat cone with a low conical profile. Third, during a climatic phase, copious flows of andesitic and basaltic lavas were erupted. During this phase, the current cones of Greater and Lesser Ararat were formed as eruptions along subsidiary fissures and cracks and flank occurred. Finally, the volcanic eruptions at Mount Ararat transitioned into a flank eruption phase, during which a major north–south-trending fault offset the two cones that developed along with a number of subsidiary fissures and cracks on the volcano's flanks.

Along this fault and the subsidiary fissures and cracks, a number of parasitic cones and domes were built by minor eruptions. One subsidiary cone erupted voluminous basalt and andesite lava flows. They flowed across the Doğubeyazıt plain and along the southerly flowing Sarısu River. These lava flows formed black ʻaʻā and pāhoehoe lava flows that contain well preserved lava tubes.[6] The radiometric dating of these lava flows yielded radiometric ages of 0.4, 0.48 and 0.81 Ma.[68] Overall, radiometric ages obtained from the volcanic rocks erupted by Mount Ararat range from 1.5 to 0.02 Ma.[6]

Recent volcanic and seismic activity

The chronology of Holocene volcanic activity associated with Mount Ararat is documented by either archaeological excavations, oral history, historical records, or a combination of these data, which provide evidence that volcanic eruptions of Mount Ararat occurred in 2500–2400 BC, 550 BC, possibly in 1450 AD and 1783 AD, and definitely in 1840 AD. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that explosive eruptions and pyroclastic flows from the northwest flank of Mount Ararat destroyed and buried at least one Kura–Araxes culture settlement and caused numerous fatalities in 2500–2400 BC. Oral histories indicated that a significant eruption of uncertain magnitude occurred in 550 BC and minor eruptions of uncertain nature might have occurred in 1450 AD and 1783 AD.[69][66][67][70] According to the interpretation of historical and archaeological data, strong earthquakes not associated with volcanic eruptions also occurred in the area of Mount Ararat in 139, 368, 851–893, and 1319 AD. During the 139 AD earthquake, a large landslide that caused many casualties and was similar to the 1840 AD landslide originated from the summit of Mount Ararat.[66][67][71]

1840 eruption

A phreatic eruption occurred on Mount Ararat on July 2, 1840 and pyroclastic flow from radial fissures on the upper north flank of the mountain and a possibly associated earthquake of magnitude 7.4 that caused severe damage and numerous casualties. Up to 10,000 people died in the earthquake, including 1,900 villagers in the village of Akhuri (Armenian: Akori, modern Yenidoğan) who were killed by a gigantic landslide and subsequent debris flow. In addition, this combination of landslide and debris flow destroyed the Armenian monastery of St. Jacob near Akori, the town of Aralik, several villages, and Russian military barracks. It also temporarily dammed the Sevjur (Metsamor) River.[69][66][67][70]

Ascents

The 13th century missionary William of Rubruck wrote that "Many have tried to climb it, but none has been able."[72]

Religious objections

The Armenian Apostolic Church was historically opposed to ascents of Ararat on religious grounds. Thomas Stackhouse, an 18th-century English theologian, noted that "All the Armenians are firmly persuaded that Noah's ark exists to the present day on the summit of Mount Ararat, and that in order to preserve it, no person is permitted to approach it."[73] In response to its first ascent by Parrot and Abovian, one high-ranking Armenian Apostolic Church clergyman commented that to climb the sacred mountain was "to tie the womb of the mother of all mankind in a dragonish mode". By contrast, in the 21st century to climb Ararat is "the most highly valued goal of some of the patriotic pilgrimages that are organized in growing number from Armenia and the Armenian diaspora".[74]

First ascent

The first recorded ascent of the mountain in modern times took place on 9 October [O.S. 27 September] 1829.[75][76][77][78] The Baltic German naturalist Friedrich Parrot of the University of Dorpat arrived at Etchmiadzin in mid-September 1829, almost two years after the Russian capture of Yerevan, for the sole purpose of exploring Ararat.[79] The prominent Armenian writer Khachatur Abovian, then a deacon and translator at Etchmiadzin, was assigned by Catholicos Yeprem, the head of the Armenian Church, as interpreter and guide.

Parrot and Abovian crossed the Aras River into the district of Surmali and headed to the Armenian village of Akhuri on the northern slope of Ararat, 1,220 metres (4,000 ft) above sea level. They set up a base camp at the Armenian monastery of St. Hakob some 730 metres (2,400 ft) higher, at an elevation of 1,943 metres (6,375 ft). After two failed attempts, they reached the summit on their third attempt at 3:15 p.m. on October 9, 1829.[76][80] The group included Parrot, Abovian, two Russian soldiers – Aleksei Zdorovenko and Matvei Chalpanov – and two Armenian Akhuri villagers – Hovhannes Aivazian and Murad Poghosian.[81] Parrot measured the elevation at 5,250 metres (17,220 ft) using a mercury barometer. This was not only the first recorded ascent of Ararat, but also the second highest elevation climbed by man up to that date outside of Mount Licancabur in the Chilean Andes. Abovian dug a hole in the ice and erected a wooden cross facing north.[82] Abovian also picked up a chunk of ice from the summit and carried it down with him in a bottle, considering the water holy. On 8 November [O.S. 27 October] 1829, Parrot and Abovian together with the Akhuri hunter Sahak's brother Hako, acting as a guide, climbed up Lesser Ararat.[83]

Later notable ascents

Other early notable climbers of Ararat included Russian climatologist and meteorologist Kozma Spassky-Avtonomov (August 1834), Karl Behrens (1835), German mineralogist and geologist Otto Wilhelm Hermann von Abich (29 July 1845),[84] British politician Henry Danby Seymour (1848)[85] and British army officer Major Robert Stuart (1856).[86] Later in the 19th century, two British politicians and scholars—James Bryce (1876)[87] and H. F. B. Lynch (1893)[88][89]—climbed the mountain. The first winter climb was by Turkish alpinist Bozkurt Ergör, the former president of the Turkish Mountaineering Federation, who climbed the peak on 21 February 1970.[90]

Resting-place of Noah's Ark

Origin of the tradition

According to the Book of Genesis of the Old Testament, Noah's Ark landed on the "mountains of Ararat" (Genesis 8:4). Historians and Bible scholars generally agree that "Ararat" is the Hebrew name of Urartu, the geographical predecessor of Armenia; they argue that the word referred to the wider region at the time and not specifically to Mount Ararat.[h] The phrase is translated as "mountains of Armenia" (montes Armeniae) in the Vulgate.[97] Nevertheless, Ararat is traditionally considered the resting-place of Noah's Ark,[98] and, thus, regarded as a biblical mountain.[99][100]

Mount Ararat has been associated with the Genesis account since the 11th century,[95] and Armenians began to identify it as the ark's landing place during that time.[101] F. C. Conybeare wrote that the mountain was "a center and focus of pagan myths and cults… and it was only in the eleventh century, after these had vanished from the popular mind, that the Armenian theologians ventured to locate on its eternal snows the resting-place of Noah's ark".[102] William of Rubruck is usually considered the earliest reference for the tradition of Mount Ararat as the landing place of the ark in European literature.[72][94][103] John Mandeville is another early author who mentioned Mount Ararat, "where Noah's ship rested, and it is still there".[104][105][i]

The ark on Ararat was often depicted in mappae mundi as early as the 11th century.[107][j]

- Medieval and early modern depictions of Noah's Ark on Ararat

Prevalence of the tradition

Most Christians, including most of Western Christianity,[103] identify Mount Ararat with the biblical mountains of Ararat "largely because it would have been the first peak to emerge from the receding flood waters".[98][n] H. G. O. Dwight wrote in 1856 that it is "the general opinion of the learned in Europe" that the Ark landed on Ararat.[123] James Bryce wrote that the ark rested upon a "mountain in the district which the Hebrews knew as Ararat, or Armenia" in an 1878 article for the Royal Geographical Society, and he added that the biblical writer must have had Mount Ararat in mind because it is so "very much higher, more conspicuous, and more majestic than any other summit in Armenia".[87]

In 2001 Pope John Paul II declared in his homily in Yerevan's St. Gregory the Illuminator Cathedral: "We are close to Mount Ararat, where tradition says that the Ark of Noah came to rest."[124] Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, the head of the Russian Orthodox Church, also mentioned it as the resting-place of Noah's Ark in his speech at Etchmiadzin Cathedral in 2010.[125]

Those critical of this view-point out that Ararat was the name of the country at the time when Genesis was written, not specifically the mountain. Arnold wrote in his 2008 Genesis commentary, "The location 'on the mountains' of Ararat indicates not a specific mountain by that name, but rather the mountainous region of the land of Ararat".[15]

Searches

Ararat has traditionally been the main focus of the searches for Noah's Ark.[98] Augustin Calmet wrote in his 1722 biblical dictionary: "It is affirmed, but without proof, that there are still remains of Noah's ark on the top of this mountain; but M. de Tournefort, who visited this spot, has assured us there was nothing like it; that the top of mount Ararat is inaccessible, both by reason of its great height, and of the snow which perpetually covers it."[121] Archaeological expeditions, sometimes supported by evangelical and millenarian churches, have been conducted since the 19th century in search of the ark.[126] According to a 1974 book, around 200 people from more than 20 countries claimed to have seen the Ark on Ararat since 1856.[127] A fragment from the ark supposedly found on Ararat is on display at the museum of Etchmiadzin Cathedral, the center of the Armenian Church.[128] Despite numerous reports of ark sightings (e.g. Ararat anomaly) and rumors, "no scientific evidence of the ark has emerged".[129] Searches for Noah's Ark are considered by scholars an example of pseudoarchaeology.[130][131] Kenneth Feder writes: "As the flood story itself is unsupported by any archaeological evidence, it is not surprising that there is no archaeological evidence for the existence of an impossibly large boat dating to 5,000 years ago."[132]

Significance for Armenians

Symbolism

Despite lying outside the borders of modern Armenia, Ararat has historically been associated with Armenia,[141] and Armenians have been called the "people of Ararat".[142][143] It is widely considered the country's principal national symbol.[144] The image of Ararat, usually framed within a nationalizing discourse, is ubiquitous in everyday material culture in Armenia.[145] Tsypylma Darieva argues that Armenians have "a sense of possession of Ararat in the sense of symbolic cultural property".[146]

There is historical and modern mountain worship around it among Armenians.[147][148][149] Ararat is known as the "holy mountain" of the Armenian people.[150][133][151] It was principal to the pre-Christian Armenian mythology, where it was the home of the gods.[152] With the rise of Christianity, the mythology associated with pagan worship of the mountain was lost.[153]

Ararat was the geographical center of ancient Armenia.[o] In the 19th-century era of romantic nationalism, when an Armenian state did not exist, Ararat symbolized the historical Armenian nation-state.[158] In 1861 Armenian poet Mikael Nalbandian, witnessing the Italian unification, wrote to Harutiun Svadjian in a letter from Naples: "Etna and Vesuvius are still smoking; is there no fire left in the old volcano of Ararat?"[159]

Theodore Edward Dowling wrote in 1910 that Ararat and Etchmiadzin are the "two great objects of Armenian veneration". He noted that the "noble snowy mountain takes the place, in the estimation of the Armenians, that Mount Sinai and the traditional Mount Zion do among the adherents of other Eastern Christians".[160][161] Jonathan Smele called Ararat and the medieval capital of Ani the "most cherished symbols of Armenian identity".[162]

Myth of origin

The Genesis flood narrative was linked to the Armenian myth of origin by the early medieval historian Movses Khorenatsi. In his History of Armenia, he wrote that Noah and his family first settled in Armenia and later moved to Babylon. Hayk, a descendant of Japheth, a son of Noah, revolted against Bel (the biblical Nimrod) and returned to the area around Mount Ararat, where he established the roots of the Armenian nation. He is thus considered the legendary founding father (patriarch) and the name giver of the Armenian people.[163][164] According to Razmik Panossian, this legend "makes Armenia the cradle of all civilisation since Noah's Ark landed on the 'Armenian' mountain of Ararat. [...] it connects Armenians to the biblical narrative of human development. [...] it makes Mount Ararat the national symbol of all Armenians, and the territory around it the Armenian homeland from time immemorial."[165]

Coat of arms of Armenia

Mount Ararat has been depicted on the coat of arms of Armenia consistently since 1918. The First Republic's coat of arms was designed by architect Alexander Tamanian and painter Hakob Kojoyan. This coat of arms was readopted by the legislature of the Republic of Armenia on April 19, 1992, after Armenia regained its independence. Mount Ararat is depicted along with the ark on its peak on the shield on an orange background.[166] The emblem of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (Soviet Armenia) was created by the painters Martiros Saryan and Hakob Kojoyan in 1921.[167] Mount Ararat is depicted in the center and makes up a large portion of it.[168]

-

Current Republic (1992–)

It is also depicted on the emblem and flag of Yerevan since 2004. It is portrayed on the breast of a lion along with the Armenian eternity sign.[169] The mountain appears on the emblem of the Armenian Catholic Ordinariate of Armenia and Eastern Europe.[170]

Ararat appeared on the coat of arms of the Armenian Oblast and the Georgia-Imeretia Governorate (image), subdivisions of the Russian Empire that included the northern flanks of the mountain. They were adopted in 1833 and 1843, respectively.[171]

Symbol of genocide and territorial claims

In the aftermath of the Armenian genocide of 1915, Ararat came to represent the destruction of the native Armenian population of eastern Turkey (Western Armenia) in the national consciousness of Armenians.[p][173] Ari L. Goldman noted in 1988: "In most Armenian homes in the modern diaspora, there are pictures of Mount Ararat, a bittersweet reminder of the homeland and national aspirations."[174]

Ararat has become a symbol of Armenian efforts to reclaim its "lost lands", i.e. the areas west of Ararat that are now part of Turkey that had significant Armenian populations before the genocide.[175] Adriaans noted that Ararat is featured as a sanctified territory for the Armenians in everyday banal irredentism.[176] Stephanie Platz wrote: "Omnipresent, the vision of Ararat rising above Yerevan and its outskirts constantly reminds Armenians of their putative ethnogenesis … and of their exile from Eastern Anatolia after the Armenian genocide of 1915."[177]

Turkish political scientist Bayram Balci argues that regular references to the Armenian Genocide and Mount Ararat "clearly indicate" that the border with Turkey is contested in Armenia.[180] Since independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the Armenian government has not made official claims to any Turkish territory,[180][181] however the Armenian government has avoided "an explicit and formal recognition of the existing Turkish-Armenian border".[182] In a 2010 interview with Der Spiegel, Armenian President Serzh Sargsyan was asked whether Armenia wants "Mount Ararat back". Sargsyan, in response, said that "No one can take Mount Ararat from us; we keep it in our hearts. Wherever Armenians live in the world today, you will find a picture of Mount Ararat in their homes. And I feel certain that a time will come when Mount Ararat is no longer a symbol of the separation between our peoples, but an emblem of understanding. But let me make this clear: Never has a representative of Armenia made territorial demands. Turkey alleges this—perhaps out of its own bad conscience?"[183]

The most prominent party to lay claims to eastern Turkey is the nationalist Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun). which claims it as part of what it considers United Armenia.[184] In various settings, several notable individuals such as German historian Tessa Hofmann,[q] Slovak conservative politician František Mikloško,[r] Lithuanian political scientist and Soviet dissident Aleksandras Štromas[s] have spoken in support of Armenian claims over Mt. Ararat.

Cultural depictions

Levon Abrahamian noted that Ararat is visually present for Armenians in reality (it can be seen from many houses in Yerevan and settlements in the Ararat plain), symbolically (through many visual representations, such as on Armenia's coats of arms), and culturally—in numerous and various nostalgic poetical, political, architectural representation.[189] The first three postage stamps issued by Armenia in 1992 after achieving independence from the Soviet Union depicted Mount Ararat.[188]

Mount Ararat has been depicted on various Armenian dram banknotes issued in 1993–2001; on the reverse of the 10 dram banknotes issued in 1993, on the reverse of the 50 dram banknotes issued in 1998, on the obverse of the 100 and 500 dram banknotes issued in 1993, and on the reverse of the 50,000 dram banknotes issued in 2001. It was also depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 100 lira banknotes of 1972–1986.[t]

Ararat is depicted on the logo of two of Armenia's leading university, the Yerevan State University, on the logos of Football Club Ararat Yerevan (since the Soviet times) and the Football Federation of Armenia. The logo of Armavia, Armenia's now defunct flag carrier, also depicted Ararat.

Ararat (now Etchmiadzin) was the name of the Armenian Church's official magazine, the first periodical in Armenia, launched in 1868.[190] The publications of the Social Democrat Hunchakian Party in Lebanon (Ararad daily) and California, U.S. (Massis weekly) are both named for the mountain.

The Ararat brandy, produced by the Yerevan Brandy Company since 1887, is considered the most prestigious Eastern European brandy.[191] Hotels in Yerevan often advertise the visibility of Ararat from their rooms, which is seen as a major advantage for tourists.[192][193][194]

In visual art

- Armenian

According to a 1963 source, the first Armenian artist to depict the mountain was Ivan Aivazovsky,[195] who created a painting of Ararat during his visit to Armenia in 1868.[196] However, a late 17th century map by Eremia Chelebi, an Ottoman Armenian, depicting Ararat was later discovered.[197] Other major Armenians artists who painted Ararat include Yeghishe Tadevosyan, Gevorg Bashinjaghian, Martiros Saryan,[198] and Panos Terlemezian.

-

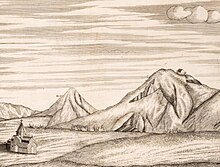

Ararat depicted vertically (right) on a 1691 map by Eremya Çelebi along with Etchmiadzin Cathedral and other churches of Vagharshapat.[197]

-

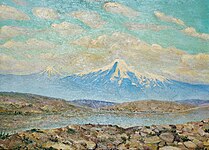

Ivan Aivazovsky, Valley of Mount Ararat, 1882

-

Yeghishe Tadevosyan, Ararat from Ejmiatsin, 1895

-

Gevorg Bashinjaghian, 1912

-

Panos Terlemezian, 1929

Ararat was depicted by non-Armenians, often in the books of European travelers in the 18th–19th centuries who visited Armenia.

-

A 1783 watercolor of the churches of Etchmiadzin with Ararat by Mikhail Matveevich Ivanov.[199][200][u]

-

Robert Ker Porter, 1821

-

"View of Ararat and the Monastery of Echmiadzin", from the 1846 English translation of Friedrich Parrot's Journey to Ararat

-

1827 Capture of Erivan by Russia, Franz Roubaud (1893)

-

James Bryce, 1877

-

H. F. B. Lynch, 1901

-

Bahruz Kangarli (1916)

In literature

Rouben Paul Adalian suggested that "there is probably more poetry written about Mount Ararat than any other mountain on earth".[153] Travel writer Rick Antonson described Ararat as the "most fabled mountain in the world".[202]

Armenian

Mount Ararat is featured prominently in Armenian literature. According to Meliné Karakashian, Armenian poets "attribute to it symbolic meanings of unity, freedom, and independence".[203] According to Kevork Bardakjian, in Armenian literature, Ararat "epitomizes Armenia and Armenian suffering and aspirations, especially the consequences of the 1915 genocide: almost total annihilation, loss of a unique culture and land [...] and an implicit determination never to recognize the new political borders".[204]

The last two lines of Yeghishe Charents's 1920 poem "I Love My Armenia" (Ես իմ անուշ Հայաստանի) read: "And in the entire world you will not find a mountaintop like Ararat's. / Like an unreachable peak of glory I love my Mount Masis."[205] In a 1926[206] poem dedicated to the mountain Avetik Isahakyan wrote: "Ages as though in second came, / Touched the grey crest of Ararat, / And passed by...! [...] It's now your turn; you too, now, / Stare at its high and lordly brow, / And pass by...!"[207]

Ararat is the most frequently cited symbol in the poetry of Hovhannes Shiraz.[204] In collection of poems, Knar Hayastani (Lyre of Armenia) published in 1958, there are many poems "with very strong nationalist overtones, especially with respect to Mount Ararat (in Turkey) and the irredentism it entailed". In one such poem, "Ktak" (Bequest), Shiraz bequeaths his son Mt. Ararat to "keep it forever, / As the language of us Armenians, as the pillar of your father's home".[208] A group of four Armenians buried Shiraz's heart at the summit of Ararat in 2006.[209]

The first lines of Paruyr Sevak's 1961 poem "We Are Few..." (Քիչ ենք, բայց հայ ենք) read: "We are few, but they say of us we are Armenians. / We do not think ourselves superior to anyone. / Clearly we shall have to accept / That we, and only we, have an Ararat".[210] In one short poem Silva Kaputikyan compares Armenia to an "ancient rock-carved fortress", the towers of which are Ararat and Aragats.

Non-Armenian

English Romantic poet William Wordsworth imagines seeing the ark in the poem "Sky-prospect — From the Plain of France".[211][212]

In his Journey to Arzrum (Путешествие в Арзрум; 1835–36), the celebrated Russian poet Aleksandr Pushkin recounted his travels to the Caucasus and Armenia at the time of the 1828–29 Russo-Turkish War.

I went out of the tent into the fresh morning air. The sun was rising. Against the clear sky one could see a white-snowcapped, twin-peaked mountain. 'What mountain is that?' I asked, stretching myself, and heard the answer: 'That's Ararat.' What a powerful effect a few syllables can have! Avidly I looked at the Biblical mountain, saw the ark moored to its peak with the hope of regeneration and life, saw both the raven and dove, flying forth, the symbols of punishment and reconciliation...[213]

Russian Symbolist poet Valery Bryusov often referred to Ararat in his poetry and dedicated two poems to the mountain,[v] which were published in 1917. Bryusov saw Ararat as the embodiment of antiquity of the Armenian people and their culture.[214]

Russian poet Osip Mandelstam wrote fondly of Ararat during his 1933 travels in Armenia. "I have cultivated in myself a sixth sense, an 'Ararat' sense", the poet wrote, "the sense of an attraction to a mountain."[215]

During his travels to Armenia, Soviet Russian writer Vasily Grossman observed Mount Ararat from Yerevan standing "high in the blue sky". He wrote that "with its gentle, tender contours, it seems to grow not out of the earth but out of the sky, as if it has condensed from its white clouds and its deep blue. It is this snowy mountain, this bluish-white sunlit mountain that shone in the eyes of those who wrote the Bible."[216]

In The Maximus Poems (1953) American poet Charles Olson, who grew up near the Armenian neighborhood in Worcester, Massachusetts, compares the Ararat Hill near his childhood home to the mountain and "imagines he can capture an Armenian's immigrant perspective: the view of Ararat Hill as Mount Ararat".[217]

The world renowned Turkish-Kurdish writer Yaşar Kemal's 1970 book entitled Ağrı Dağı Efsanesi (The Legend of Mount Ararat) is about a local myth about a poor boy and the governor's daughter. There is also an opera (1971) and a film (1975) based on that novel.[218]

In the 1984 science fiction novel Orion by Ben Bova, part three entitled “Flood” is set at an unspecified valley at the foot of Mount Ararat. The antagonist, Ahriman, floods the valley by melting the snow caps of the mountain in a bid to stop the invention of agriculture by a band of Epipalaeolithic hunter-gatherers.[219]

Several major episodes in Declare (2001) by Tim Powers take place on Mount Ararat. In the book, it is the focal point of supernatural happenings.

In popular culture

- In music

- "Holy Mountains", the 8th track of the album Hypnotize (2005) by System of a Down, an American rock band composed of four Armenian Americans, "references Mount Ararat [...] and details that the souls lost to the Armenian Genocide have returned to rest here".[221]

- "Here's to You Ararat" is a song from the 2006 album How Much is Yours of Arto Tunçboyacıyan's Armenian Navy Band.[222]

- In film

- The 2002 film Ararat by Armenian-Canadian filmmaker Atom Egoyan features Mount Ararat prominently in its symbolism.[223]

- The 2011 documentary film Journey to Ararat on Parrot and Abovian's expedition to Ararat was produced in Estonia by filmmaker Riho Västrik.[224][225] It was screened at the Golden Apricot International Film Festival in Yerevan in 2013.[226]

- In commercials

- In one of Turkish Airlines commercials (2014), András Földvári, then head of marketing in Turkish Airlines' Hungary Office, flew from Budapest to Iğdır to explore the mountain and Noah's Ark.[227][228]

- Miniature wargaming

- In the lore of Warhammer 40,000, Ararat is the site of the destruction of the Thunder Warriors.

Places named for Ararat

- In Armenia

- In Armenia, four settlements are named after the mountain's two names: Ararat and Masis. All are located in the Ararat Plain. First, the village of Davalu was renamed Ararat in 1935, followed by Tokhanshalu being renamed Masis in 1945, and the workers town of Davalu's nearby cement factory also being renamed Ararat in 1947 (granted a city status in 1962). The railway town of Ulukhanlu was renamed Masis in 1950, while the former village/town of Ulukhanlu, renamed Hrazdan and then Masis in 1969. The two merged to form the urban-type settlement of Masis, the current town, in 1971.[229][230]

- In the Soviet and early post-Soviet period there were administrative divisions (shrjan or raion) called Ararat (Vedi until 1968) and Masis, formed in 1930 and 1968, respectively. They became a part of the province (marz) of Ararat in the 1995.[231]

- The name is also used in two dioceses of the Armenian Apostolic Church: the Araratian Pontifical Diocese and the Diocese of Masyatsotn, encompassing capital Yerevan and the Ararat province, respectively.[232][233]

- Elsewhere

- The Turkish province of Ağrı was named after the Turkish name of the mountain in 1927, while the provincial capital city of Karaköse was renamed to Ağrı in 1946.[234]

- In the United States, a river in Virginia and North Carolina was named Ararat after the mountain no later than 1770. An unincorporated community in North Carolina was later named after the river.[235] A township (formed in 1852)[236] and a mountain in Pennsylvania are called Ararat.[237]

- In the Australian state of Victoria, a city was named Ararat in 1840. Its local government area is also called Ararat.[238][239]

- 96205 Ararat is an asteroid named in the mountain's honor. It was discovered in 1992 by Freimut Börngen and Lutz D. Schmadel at Tautenburg Observatory in Germany. The name was proposed by Börngen.[240]

States

- Besides Ararat being the Hebrew version of Urartu,[15] this Iron Age state is often referred to as the "Araratian Kingdom" or the "Kingdom of Ararat" (Armenian: Արարատյան թագավորություն, Arartyan t'agavorut'yun) in Armenian historiography.[241] Levon Abrahamian argues that this name gives it a "biblical and an Armenian touch."[242]

- The First Republic of Armenia, the first modern Armenian state that existed between 1918 and 1920, was sometimes called the Araratian Republic or the Republic of Ararat (Armenian: Արարատյան Հանրապետություն, Araratyan hanrapetut'yun)[243][244] as it was centered in the Ararat plain.[245][246]

- In 1927 the Kurdish nationalist party Xoybûn led by Ihsan Nuri, fighting an uprising against the Turkish government, declared the independence of the Republic of Ararat (Kurdish: Komara Agiriyê), centered around Mount Ararat.[247][248]

Gallery

-

Winter in Mount Ararat.

-

Mount Ararat and Armenia-Turkey border early in the morning.

-

Seen from the International Space Station, 8 July 2011

-

From the Space Shuttle, 18 March 2001

-

View of Ararat from Khor Virap, Armenia

-

View of Ararat with the Khor Virap in the front, Armenia

-

View of Ararat from Iğdır, Turkey

-

From Doğubeyazıt

-

From Nakhchivan

-

Mt. Ararat from airplane

See also

Notes

- ^ Also known as Masis (Armenian: Մասիս).

- ^ Tiberian vocalization אֲרָרָט ʾărārāṭ; Pesher Genesis הוררט hōrārāṭ.

- ^ Other fringe theories have been proposed. In the 19th century Wilhelm Gesenius speculated, without evidence, an origin from Arjanwartah, an unattested Sanskrit word without any clear cognates, supposedly meaning "holy ground".[16][17] Historian Ashot Melkonyan links the origin of the word "Ararat" to the prefix of a number of placenames in the Armenian Highland ("ar–"), including the Armenians.[18]

- ^ The peaks are sometimes referred to in plural as Մասիսներ Masisner.[35] Greater Ararat is known as simply Masis or Մեծ Մասիս (Mets Masis, "Great/Big Masis"). While Lesser Ararat is known as Sis (Սիս)[36][37] or Փոքր Մասիս (P′ok′r Masis, "Little/Small Masis").[19][35] The word "Ararat" occurs in Armenian literature from the early medieval period, following the invention of the Armenian alphabet.[38]

- ^ Hovhannes Tumanyan tentatively proposed an etymology from purported Sanskrit words ma (mother) and sis (summit, peak or height) by citing Ivan Yagello's Hindustani-Russian Dictionary (1902). Tumanyan also referred to the Anatolian mother goddess, who was called "Ma" or "Amma" locally as a possible inspiration.[41][42] Hrachia Acharian disagreed, noting that the earlier variant is Masik‘, while Masis is the accusative case.[43]

- ^ Strabo, Geographica, XI.14.2 and XI.14.14.[47] They are also transliterated as Abus and Nibarus.[48] Abos and Nibaros are the two peaks of Ararat according to scholars such as Nicholas Adontz,[47] Vladimir Minorsky,[49] Julius Fürst.[50]

- ^ It was created by Guillaume-Joseph Grelot, according to a 2024 book by Asoghik Karapetian , director of the Etchmiadzin Museums. See still (4:55–5:01) from the book launch.[92] See also 1811 version (full engraving).[93]

- ^

- Richard James Fischer: "The Genesis text, using the plural 'mountains' (or hills), identifies no particular mountain, but points generally toward Armenia ('Ararat' being identical with the Assyrian 'Urartu') which is broadly embraces [sic] that region."[94]

- Exell, Joseph S.; Spence-Jones, Henry Donald Maurice (eds.). "Genesis". The Pulpit Commentary.

It is agreed by all that the term Ararat describes a region.

view online - Dummelow, John, ed. (1909). "Genesis". John Dummelow's Commentary on the Bible.

Ararat is the Assyrian 'Urardhu,' the country round Lake Van, in what is now called Armenia ... and perhaps it is a general expression for the hilly country which lay to the N. of Assyria. Mt. Masis, now called Mt. Ararat (a peak 17,000 ft. high), is not meant here.

view online - Bill T. Arnold: "Since the ancient kingdom of Ararat/Urartu was much more extensive geographically than this isolated location in Armenia, modern attempts to find remaints of Noah's ark here are misguided."[95]

- Vahan Kurkjian: "It has long been the notion among many Christians that Noah's Ark came to rest as the Flood subsided upon the great peak known as Mount Ararat; this assumption is based upon an erroneous reading of the 4th verse of the VIIIth chapter of Genesis. That verse does not say that the Ark landed upon Mount Ararat, but upon 'the mountains of Ararat.' Now, Ararat was the Hebrew version of the name, not of the mountain but of the country around it, the old Armenian homeland, whose name at other times and in other tongues appears variously as Erirath, Urartu, etc."[96]

- ^ Isidore of Seville (Etymologiae 14.3.35), Marco Polo, Pierre d'Ailly, and Odoric of Pordenone mention that Noah’s Ark can be found on "some mountains in Armenia, but they do not give the mountains’ name."[106]

- ^ Notable examples:

- the Anglo-Saxon mappa mundi (the Cotton map or Cottoniana, c. 1025‒50),[108]

- the Ebstorf Map (c. 1240),[109]

- the Chronica Majora (c. 1240–1253),[110]

- the Psalter world map (c. 1260),[111]

- the Hereford Mappa Mundi (c. 1300),[112]

- the Angelino Dulcert (1339),[113]

- the Catalan Atlas (c. 1375),[114]

- the Fra Mauro map (c. 1450),[115]

- the Erdapfel (c. 1490,[116]

- ^ A detail from "Map of the Holy Land with Armenia" from the Chronica Majora showing "the highest mountains of Armenia" (montes Armeniae altissimi) with Noah's Ark balanced on its two peaks.[110]

- ^ A detail from "Topography of Paradise". In the mountains above Armenia, stands Mount Ararat, shown with a rectangular-shaped ark on the summit.[117]

- ^ A detail from "The Manner how the Whole Earth was Peopled by Noah & his Descendants after the Flood" showing Noah's Ark on top of the Mountains of Ararat in Armenia.[118]

- ^ A 1722 biblical dictionary by Austin Calmet and the 1871 Jamieson-Fausset-Brown Bible Commentary both point to Ararat as the place where the ark rested.[121][122]

- ^ "...Mt. Ararat, which was the geographical center of the ancient Armenian kingdoms..."[154]

"The sacred mountain stands in the center of historical and traditional Armenia..."[155]

"To the Armenians it is the ancient sanctuary of their faith, the centre of their once famous kingdom, hallowed by a thousand traditions."[156]

One scholar defined the historic Greater Armenia as "the area about 200 miles (320 km) in every direction from Mount Ararat".[157] - ^ "The lands of Western Armenia which Mt. Ararat represent..."[158] "mount Ararat is the symbol of banal irredentism for the territories of Western Armenia"[172]

- ^ Hofmann suggested that "the return of the ruins of Ani and of Mount Ararat [by Turkey to Armenia], both in the immediate border area could be considered as a convincing gesture of Turkey's apologies and will for reconciliation."[185]

- ^ Mikloško stated at a 2010 conference on Turkey's foreign policy: "Mount Ararat [represents the] Christian heritage of Armenians. Does modern Turkey consider the possibility of giving the mount back to Armenians? The return of Ararat would be an unprecedented step to signify Turkey's willingness to build a peaceful future and promote its image at the international scene."[186]

- ^ Štromas wrote: "The Armenians would also be right to claim from Turkey the Ararat Valley, which is an indivisible part of the Armenian homeland containing the main spiritual center and supreme symbol of Armenia's nationhood, the holy Mountain of Ararat itself."[187]

- ^ Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey. Banknote Museum: 6. Emission Group – One Hundred Turkish Lira – I. Series, II. Series & III. Series.

- ^ Ivan Aivazovsky subsequently offered his version based on Ivanov's original.[201]

- ^ "К Арарату" ("To Ararat") and "Арарат из Эривани" ("Ararat from Erivan")

References

Citations

- ^ "100 World Mountains ranked by primary factor". ii.uib.no. Institutt for informatikk University of Bergen. Archived from the original on 2016-05-21. Retrieved 2016-05-09.

- ^ "Topographic map of Ağrı Dağı". opentopomap.org. Retrieved 2023-06-13.

- ^ "Ağrı Dağı Milli Parkı [Ağrı Dağı National Park]". ormansu.gov.tr (in Turkish). Republic of Turkey Ministry of Forest and Water Management. Archived from the original on 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ^ a b Waugh, Alexander (27 August 2008). "Will he, won't He? Ararat by Frank Westerman, translated by Sam Garrett". The Spectator. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ "Ağri Daği (the so-called Ararat) - Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 2024-07-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Yilmaz, Y.; Güner, Y.; Saroğlu, F. (1998). "Geology of the quaternary volcanic centres of the east Anatolia". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 85 (1–4): 173–210. Bibcode:1998JVGR...85..173Y. doi:10.1016/s0377-0273(98)00055-9. ISSN 0377-0273.

- ^ Short, Nicholas M.; Blair, Robert W., eds. (1986). "Mt. Ararat, Turkey". Geomorphology From Space: A Global Overview of Regional Landforms. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. p. 226.

- ^ a b de Planhol, X. (1986). "Ararat". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 2015-11-02. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard G. (1973). "Armenia and the Caucasus in the Genesis of the Soviet-Turkish Entente". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 4 (2): 129–147. doi:10.1017/s0020743800027409. JSTOR 162238. S2CID 162360397.

...Nationalist Turkey annexed the Surmalu district, embracing Mount Ararat, the historic symbol of the Armenian people.

- ^ de Waal, Thomas (2015). Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide. Oxford University Press. p. 86. ISBN 978-0199350698.

- ^ a b Parrot 2016, p. xxiii.

- ^ Yildiz, Kerim; Taysi, Tanyel B. (2007). The Kurds in Iran: The Past, Present and Future. London: Pluto Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0745326696.

- ^ Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014). Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus. Translated by Nora Seligman Favorov. New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0300153088.

- ^ Frymer, Tikva S.; Sperling, S. David (2008). "Ararat, Armenia". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2nd ed.). view online. Archived 2015-12-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ a b c Arnold 2008, p. 104.

- ^ Rogers, Thorold (1884). Bible Folk-Lore: A Study in Comparative Methodology. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. 21.

Ararat was thought by Gesenius to be a Sanskrit word (Arjawartah), signifying "holy ground,"...

- ^ Bonomi, Joseph (1866). "Ararat". In Fairbairn, Patrick (ed.). The Imperial Bible-Dictionary: Historical, Biographical, Geographical and Doctrinal - Volume I. Glasgow: Blackie and Son. p. 118.

- ^ Avakyan, K. R. (2009). "Աշոտ Մելքոնյան, Արարատ. Հայոց անմահության խորհուրդը [Ashot Melkonyan, Ararat. Symbol of Armenian Immortality]". Lraber Hasarakakan Gitutyunneri (in Armenian). 1 (1): 252–257. Archived from the original on 2015-11-18. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

Պատմական ճակատագրի բերումով Արարատ-Մասիսը ոչ միայն վեհության, անհասանելիության, կատարելության մարմնավորում է, այլև 1915 թ. հայոց մեծ եղեռնից ու հայ ժողովրդի հայրենազրկումից հետո՝ բռնազավթված հայրենիքի և այն նորեն իր արդար զավակներին վերադարձելու համոզումի անկրկնելի խորհրդանիշ, աշխարհասփյուռ հայության միասնականության փարոս» (էջ 8):

- ^ a b c d Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). "Armenia: The Physical Setting—Mt. Ararat". Armenia: A Historical Atlas. University of Chicago Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0-226-33228-4.

- ^ Smith, Eli (1832). "Foreign Correspondence". The Biblical Repository and Classical Review: 203.

...called by the Armenians, Masis, and by Europeans generally Ararat...

- ^ a b Bryce 1877, p. 198.

- ^ Alexander Agadjanian (15 April 2016). Armenian Christianity Today: Identity Politics and Popular Practice. Routledge. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-317-17857-6.

It is worth noting that, contrary to Armenian Apostolic Church discourse and popular knowledge, it was probably as late as the beginning of the second millennium AD when the localization of the biblical Mount Ararat was permanently moved from the highlands hemming upper Mesopotamia to Mount Masis in the heart of historical Armenian territory.

- ^ Petrosyan, Hamlet (2001). "The Sacred Mountain". In Levon Abrahamian and Nancy Sweezy (ed.). Armenian Folk Arts, Culture, and Identity. Indiana University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-253-33704-7.

When Armenians were first introduced to the biblical story of the flood, there was no special interest in the location of Mount Ararat. Most Armenian historians in the Early Middle Ages accepted the generally held Christian opinion of the time that Ararat was located near Mesopotamia in Korduk (Corduene), the southernmost province of Armenia. However, when European Crusaders on their way to free the Holy Land from Moslem rule appeared in the region in the 11th century, Armenian hopes for similar "salvation" helped to catalyze the final identification of Masis with Ararat. From the 12th century on, Catholic missionaries and other travelers to the region returned to Europe with the same story: that the mountain where the Ark landed was towering in the heart of Armenia.

- ^ Hakobian, T. Kh. (1984) [1968]. Հայաստանի պատմական աշխարհագրություն [Historical Geography of Armenia] (PDF) (in Armenian) (4th ed.). Yerevan University Press. p. 108. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-04-10.

Այրարատ անվան ստուգաբանությամբ զբաղվել են մի շարք բանասերներ և պատմաբաններ: Սակայն մինչև օրս էլ այդ անվան մեկնության շուրջ գոյություն ունեն տարբեր կարծիքներ: Ամենից հավանականը այն կարծիքն է, որն Այրարատ, Արարատ և Ուրարտու անունները համարում է հոմանիշներ:

- ^ a b c Novoseltsev 1978.

- ^ "Nuh'un Gemisi Efsanesi". agri.ktb.gov.tr. Retrieved 2024-01-05.

- ^ Dalton, Robert H. (2004). Sacred Places of the World: A Religious Journey Across the Globe. Abhishek. p. 133. ISBN 9788182470514.

The Turkish name for Mt Ararat is Agri Dagi (which means mountain of pain).

- ^ McCarta, Robertson (1992). Turkey (2nd ed.). Nelles. p. 210. ISBN 9783886184019.

(Turkish: Agri Dagi, "Mount of Sorrows")

- ^ "Yenidoğan". Index Anatolicus (in Turkish). Retrieved 7 December 2023.

- ^ a b Sarıkaya, Mehmet Akif (2012). "Recession of the ice cap on Mount Ağrı (Ararat), Turkey, from 1976 to 2011 and its climatic significance". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 46: 190–194. Bibcode:2012JAESc..46..190S. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2011.12.009.

- ^ "Xortekî tirk dixwaze bi bîsîklêtê xwe ji çiyayê Agirî berde xwarê" (in Kurdish). Rudaw Media Network. 19 June 2014. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ Akkuş, Murat. "Ağrı Dağı'nın adı "Ararat" olmalı". basnews. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ a b Jastrow, Morris Jr.; Kent, Charles Foster (1902). "Ararat". Jewish Encyclopedia Volume II. New York, NY: Funk & Wagnalls Co. p. 73.

The mountain itself is known as Ararat only among Occidental geographers. The Armenians call it Massis, the Turks Aghri Dagh, and the Persians Koh i Nuh, or "the mountain of Noah."

view online Archived 2015-11-25 at the Wayback Machine - ^ Avetisyan, Kamsar (1979). Հայրենագիտական էտյուդներ [Armenian studies sketches] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Sovetakan grogh. p. 14. Archived from the original on 2015-11-27. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

Հայերը Արարատը անվանում են Մասիս...

- ^ a b "Մասիսներ" [Masisner]. encyclopedia.am (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 2016-08-16. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ a b Peroomian, Rubina (2007). "Historical Memory: Threading the Contemporary Literature of Armenia". In Hovannisian, Richard (ed.). The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Transaction Publishers. p. 113. ISBN 9781412835923.

...the majestic duo of Sis and Masis (the two peaks of Mount Ararat) that hover above the Erevan landscape are constant reminders of the historical injustice.

- ^ Delitzsch, Franz (2001). New Commentary on Genesis. Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 274. ISBN 978-1-57910-813-7.

The Armenians call Little Ararat sis and Great Ararat masis, whence it seems that great, the meaning of meds, is contained in ma.

- ^ Hovhannisyan, L. Sh. (2016). Բառերի մեկնությունը հինգերորդ դարի հայ մատենագրուտյան մեջ [Interpretation of words in 5th century Armenian manuscripts] (in Armenian). Yerevan: Gitutyun. p. 61.

- ^ Khorenatsi 1978, p. 91.

- ^ a b Petrossyan 2010, p. 221.

- ^ "Հայերեն գավառական բառարան". Հովհ. Թումանյան. Երկերի ժողովածու. Չորրորդ հատոր. Քննադատություններ և հրապարակախոսություն. 1892-1921 [Hovh. Tumanyan: Collected Works. Volume IV: Criticism and Journalism, 1892-1921] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan: Haypethrat. 1951. pp. 399–409.

- ^ Gasparian, G. K. (1969). "Հովհաննես Թումանյանի բառարանագիտական դիտողությունները [Lexicographical Remarks of Hovhannes Tumanian]". Patma-Banasirakan Handes (in Armenian). 3: 66.

- ^ Stepanian, Garnik [in Armenian] (2013). Հրաչյա Աճառյան. Կյանքը և գործը [Hrachia Acharian: Life and Work] (PDF) (in Armenian). Yerevan University Press. p. 175. ISBN 978-5-8084-1787-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-08-19.

չի ընդունում Թումանյանի ստուգաբանական կարծիքները, մանավանդ հատուկ անունների խնդրում, օրինակ' Սիս Մասիս բառերի Թումանյանական բացատրությունը: Թումանյանի կարծիքով Մասիս անունը առաջացել է սանսկրիտ Մա և Սիս- գագաթ բառերից, մինչդեռ Աճառյանն իր նամակում գտնում է, որ Մասիս բառի հին ձևը եղել է Մասիք, թե Մասիս նրա հայցական ձևն է, ուրեմն բուն բառը պետք է լինի մասի, արմատը մաս և այլն:

- ^ Petrosyan 2016, p. 72.

- ^ Armen Petrosyan. "Biblical Mt. Ararat: Two Identifications". Comparative Mythology. December 2016. Vol. 2. Issue 1. pp. 68–80.

- ^ As of 2022, there were 5489 and 882 people named Ararat and Masis, respectively, in Armenia's voters' list

- "Արարատ (Ararat)". anun.am (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 5 January 2023.

- "Մասիս (Masis)". anun.am. Archived from the original on 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b Petrossyan 2010, p. 220.

- ^ Jones, Horace Leonard, ed. (1928). "XI.14". The Geography of Strabo. Harvard University Press. view Book XI, Chapter 14 online

- ^ Minorsky, V. (1944). "Roman and Byzantine Campaigns in Atropatene". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 11 (2): 243–265. doi:10.1017/S0041977X0007244X. JSTOR 609312. S2CID 129323675.

Although what Strabo means by Abos seems to be the southern spurs of Mt. Ararat...

- ^ Julius Fürst cited in Exell, Joseph; Jones, William; Barlow, George; Scott, W. Frank; et al. (1892). The Preacher's Complete Homiletical Commentary. "...the present Aghri Dagh or the great Ararat (Pers. Kuhi Nuch, i.e. Noah's mountain, in the classics ὁ ἄβος, Armen. massis)..." (Furst.) view online Archived 2016-08-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Ağrı – Mount Ararat". Republic of Turkey Ministry of culture and tourism (kultur.gov.tr). 2005.

- ^ "Mount Agri (Ararat)". anatolia.com. 2003. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

the Serdarbulak lava plateau (2600 m) stretches out between the two pinnacles.

- ^ "Doğubayazıt sazlığının (Ağrı-Türkiye) arazi örtüsü deseninde meydana gelen değişimlerin ekolojik sonuçları üzerine bir analiz" (in Turkish). Doğu Coğrafya Dergisi-Atatürk University. December 20, 2021. p. 3.

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Springfield, Massachusetts: Merriam-Webster. 2001. p. 63. ISBN 9780877795469.

- ^ Haggett, Peter, ed. (2002). "Turkey". Encyclopedia of World Geography: The Middle East (2nd ed.). Marshall Cavendish. p. 2026. ISBN 978-0-7614-7289-6.

- ^ Hartemann, Frederic; Hauptman, Robert (2005). The Mountain Encyclopedia. Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8108-5056-9.

- ^ Galichian, Rouben (2004). Historic Maps of Armenia: The Cartographic Heritage. I.B. Tauris. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-86064-979-0.

- ^ Kurter, Ajun [in Turkish] (20 May 1988). "Glaciers of the Middle East and Africa: Turkey" (PDF). United States Geological Survey Professional Paper 1386-G. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017.

- ^ "Maps of Ararat - Ararat Map, Turkey (Agri Dagi)". turkeyodyssey.com. Terra Anatolia. Archived from the original on 2007-02-25.

- ^ According to Petter E. Bjørstad, Head of Informatics Department at the University of Bergen (Norway). "Ararat Trip Report". ii.uib.no. August 2007. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017.

I measured the summit elevation, averaging more than 300 samples in my GPS, it settled on 5132 meter, 5 meter lower than the often quoted 5137 figure. This clearly shows that the 5165 meter elevation that many sources use is wrong. The summit is a snow ridge with no visible rock anywhere. Thus, the precise elevation will change with the seasons and could definitely be influenced by climate change (global warming). Later GPS measurements in Iran suggested that the GPS data may be about 10 meter too high also in this part of the world. This would in fact point in the direction of a true Ararat elevation around 5125 meter.

- ^ a b c Blumenthal, M. M. (1958). "Vom Agrl Dag (Ararat) zum Kagkar Dag. Bergfahrten in nordostanatolischen Grenzlande". Die Alpen (in German). 34: 125–137.

- ^ a b Sarıkaya, Mehmet Akif; Tekeli, A. E. (2014). "Satellite inventory of glaciers in Turkey". In J. S. Kargel; et al. (eds.). Global Land Ice Measurements from Space. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. 465–480. ISBN 978-3540798170.

- ^ Yalcin, Mustafa (2020). "A GIS-Based Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Model for Determining Glacier Vulnerability". ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 9 (3): 180. Bibcode:2020IJGI....9..180Y. doi:10.3390/ijgi9030180.

- ^ a b Birman, J. H. (1968). "Glacial Reconnaissance in Turkey". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 79 (8): 1009–1026. Bibcode:1968GSAB...79.1009B. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1968)79[1009:GRIT]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Dewey, J. F.; Hempton, M. R.; Kidd, W. S. F.; Saroglum, F.; Sengὃr, A. M. C. (1986). "Shortening of continental lithosphere: the neotectonics of Eastern Anatolia – a young collision zone". In Coward, M. P.; Ries, A. C. (eds.). Collision Tectonics. Geological Society of London. pp. 3–36.

- ^ a b c d Karakhanian, A.; Djrbashian, R.; Trifonov, V.; Philip, H.; Arakelian, S.; Avagian, A. (2002). "Holocene–Historical Volcanism and Active Faults as Natural Risk Factor for Armenia and Adjacent Countries". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 113 (1): 319–344. Bibcode:2002JVGR..113..319K. doi:10.1016/s0377-0273(01)00264-5.

- ^ a b c d Karakhanian, A.S.; Trifonov, V.G.; Philip, H.; Avagyan, A.; Hessami, K.; Jamali, F.; Bayraktutan, M. S.; Bagdassarian, H.; Arakelian, S.; Davtian, V.; Adilkhanyan, A. (2004). "Active faulting and natural hazards in Armenia, Eastern Turkey and North-Western Iran". Tectonophysics. 380 (3–4): 189–219. Bibcode:2004Tectp.380..189K. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2003.09.020.

- ^ Allen, Mark B.; Mark, Darren F.; Kheirkhah, Monireh; Barfod, Dan; Emami, Mohammad H.; Saville, Christopher (2011). "40Ar/39Ar dating of Quaternary lavas in northwest Iran: constraints on the landscape evolution and incision rates of the Turkish–Iranian plateau" (PDF). Geophysical Journal International. 185 (3): 1175–1188. Bibcode:2011GeoJI.185.1175A. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.2011.05022.x.

- ^ a b Siebert, L., T. Simkin, and P. Kimberly (2010) Volcanoes of the world, 3rd ed. University of California Press, Berkeley, California. 551 pp. ISBN 978-0-520-26877-7.

- ^ a b Haroutiunian, R. A. (2005). "Катастрофическое извержение вулкана Арарат 2 июля 1840 года" [Catastrophic eruption of volcano Ararat on 2 july, 1840]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia: Earth Sciences (in Russian). 58 (1): 27–35. ISSN 0515-961X. Archived from the original on 2015-12-07. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ^ Taymaz, Tuncay; Eyidog̃an, Haluk; Jackson, James (1991). "Source parameters of large earthquakes in the East Anatolian fault zone (Turkey)". Geophysical Journal International. 106 (3): 537–550. Bibcode:1991GeoJI.106..537T. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.1991.tb06328.x.

- ^ a b William of Rubruck (1998). The Journey of William of Rubruck to the Eastern Parts of the World, 1253–55. Translated by W. W. Rockhill. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. p. 269–270. ISBN 978-81-206-1338-6.

[...] mountains in which they say that Noah's ark rests; and there are two mountains, the one greater than the other; and the Araxes flows at their base [...] Many have tried to climb it, but none has been able. [...] An old man gave me quite a good reason why one ought not to try to climb it. They call the mountain Massis [...] "No one," he said, "ought to climb up Massis; it is the mother of the world."

- ^ Stackhouse, Thomas (1836). A History of the Holy Bible. Glasgow: Blackie and Son. p. 93.

- ^ Siekierski, Konrad (2014). "'One Nation, One Faith, One Church': The Armenian Apostolic Church and the Ethno-Religion in Post-Soviet Armenia". In Agadjanian, Alexander (ed.). Armenian Christianity Today: Identity Politics and Popular Practice. Ashgate Publishing. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-4724-1273-7.

- ^ Parrot 2016, p. 139

- ^ a b Randveer, Lauri (October 2009). "How the Future Rector Conquered Ararat". University of Tartu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-25. Retrieved 2015-11-25.

- ^ Khachaturian, Lisa (2011). Cultivating Nationhood in Imperial Russia: The Periodical Press and the Formation of a Modern Armenian Identity. Transaction Publishers. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4128-1372-3.

- ^ Milner, Thomas (1872). The Gallery of Geography: A Pictorial and Descriptive Tour of the World, Volume 2. W.R. M'Phun & Son. p. 783.

Great Ararat was ascended for the first time by Professor Parrot, October 9, 1829...

- ^ Giles, Thomas (27 April 2016). "Friedrich Parrot: The man who became the 'father of Russian mountaineering'". Russia Beyond the Headlines. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ Ketchian, Philip K. (December 24, 2005). "Climbing Ararat: Then and Now". The Armenian Weekly. 71 (52). Archived from the original on September 8, 2009.

- ^ Parrot 2016, p. 142.

- ^ Parrot 2016, p. 141-142.

- ^ Parrot 2016, p. 183.

- ^ Fairbairn, Patrick (1866). "Ararat". The Imperial Bible-Dictionary: Historical, Biographical, Geographical and Doctrinal – Volume I. p. 119.

- ^ Polo, Marco; Yule, Henry (2010). The Book of Ser Marco Polo, the Venetian: Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-108-02206-4.

- ^ B. J. Corbin and Rex Geissler, The Explorers of Ararat: And the Search for Noah's Ark, 3rd. edition (2010), chap. 3.

- ^ a b Bryce, James (1878). "On Armenia and Mount Ararat". Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 22 (3): 169–186. doi:10.2307/1799899. JSTOR 1799899.

- ^ Lynch, H. F. B. (1893). "The ascent of Ararat". The Geographical Journal. 2: 458.

- ^ Lynch, H. F. B. (1901). Armenia, travels and studies. Volume I: The Russian Provinces. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 176.

- ^ "Conquering the legendary Mount Ararat". Hürriyet Daily News. 15 January 2006. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- ^ "The Travels of Sir John Chardin into Persia and the East Indies – First Edition – London, 1686 – Engravings and a Map". Kedem Auction House. December 21, 2021. Archived from the original on 5 March 2024. engraving archived

- ^ "Կայացել է «Արփիափայլ և երփնազան Սուրբ Էջմիածին» պատկերագրքի շնորհադեսը" (in Armenian). Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin. March 5, 2024. Archived from the original on 8 August 2024.

- ^ "Ecs-miazin nommée communément les trois eglises". repository.library.brown.edu. Brown Digital Repository, Brown University Library. Archived from the original on 13 December 2023.

- ^ a b Fischer, Richard James (2007). "Mount Ararat". Historical Genesis: From Adam to Abraham. University Press of America. pp. 109–111. ISBN 9780761838074. Archived from the original on 2019-01-28. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

- ^ a b Arnold 2008, p. 105.

- ^ Kurkjian, Vahan (1964) [1958]. A History of Armenia. New York: Armenian General Benevolent Union of America. p. 2.

- ^ Room, Adrian (1997). Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings. McFarland. p. 34. ISBN 9780786401727.

- ^ a b c Vos, Howard F. (1982). "Flood (Genesis)". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Volume Two: E-J (fully revised ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-8028-3782-0.

- ^ Tremblais, Jean-Louis (16 July 2011). "Ararat, montagne biblique". Le Figaro (in French). Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- "Biblical mountain's glaciers shrinking". News24. 8 August 2010. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- ^ a b Avagyan, Ṛafayel (1998). Yerevan—heart of Armenia: meetings on the roads of time. Union of Writers of Armenia. p. 17.

The sacred biblical mountain prevailing over Yerevan was the very visiting card by which foreigners came to know our country.

- ^ Bailey, Lloyd R. (1990). "Ararat". In Mills, Watson E.; Bullard, Roger Aubrey (eds.). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. Mercer University Press. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-86554-373-7. Archived from the original on 2019-01-28. Retrieved 2016-11-03.

...the local (Armenian) population called Masis and which they began to identify as the ark's landing place in the eleventh-twelfth centuries.

- ^ Conybeare, F. C. (1901). "Reviewed Work: Ararat und Masis. Studien zur armenischen Altertumskunde und Litteratur by Friedrich Murad". The American Journal of Theology. 5 (2): 335–337. doi:10.1086/477703. JSTOR 3152410.

- ^ a b Spencer, Lee; Lienard, Jean Luc (2005). "The Search for Noah's Ark". Southwestern Adventist University. Archived from the original on 2015-03-14. Retrieved 2015-11-03. (archived)

- ^ Mandeville, John (2012). The Book of Marvels and Travels. Translated by Anthony Bale. Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780199600601.

- ^ Mandel, Jerome (2013). "Ararat, Mount". In Friedman, John Block; Figg, Kristen Mossler (eds.). Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 978-1-135-59094-9.

- ^ a b Van Duzer, Chet (2020). Martin Waldseemüller's 'Carta marina' of 1516: Study and Transcription of the Long Legends. Springer. pp. 35–37. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22703-6. ISBN 978-3-030-22703-6.

- ^ Unger, Richard W. (2010). Ships on Maps: Pictures of Power in Renaissance Europe. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 33. ISBN 9781349312078.

Mappaemundi did not have ships as part of their repertoire of illumination. Now and again but by no means universally Noah's Ark did turn up, perched often on Mount Ararat where it had come to rest after the Flood.

- ^ Appleton, Helen (December 2018). "The northern world of the Anglo-Saxon mappa mundi". Anglo-Saxon England. 47: 275–305. doi:10.1017/S0263675119000061. ISSN 0263-6751.

The tribes of Israel are allocated areas and the locations of God's covenants with man on Sinai and Ararat are marked, the latter with a small drawing of the Ark.

- ^ Pischke, G. (11 July 2014). "The Ebstorf Map: tradition and contents of a medieval picture of the world" (PDF). History of Geo- and Space Sciences. 5 (2): 155–161. Bibcode:2014HGSS....5..155P. doi:10.5194/hgss-5-155-2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-11-06.

Noah's Ark on Mount Ararat (Fig. 3a)

- ^ a b Mann, C. Griffith (October 15, 2018). "Armenia! In the Shadows of Mount Ararat". metmuseum.org. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 10 August 2023.

- ^ Fein, Ariel (June 6, 2022). "The Catalan Atlas". Smarthistory. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023.

The biblical whale that swallowed the prophet Jonah swims in an ocean while Noah's ark rests atop Mount Ararat.

- ^ Wogan-Browne, Jocelyn (1991). "Reading the world: the Hereford mappa mundi". Parergon. 9 (1): 117–135. doi:10.1353/pgn.1991.0019. ISSN 1832-8334.

shown, in the ark, perched on top of Mount Ararat near the centre of the Hereford map

- ^ Evans, Helen C. (2018). "Maps including Armenia". Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages. Metropolitan Museum of Art and Yale University Press. p. 300. ISBN 9781588396600. OCLC 1028910888.

- ^ a b "Panel V". The Cresques Project. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023.

Mons Ararat...

- ^ Parker, Philip (2022). Atlas of Atlases. London: Ivy Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780711267497.

He also shows Gog and Magog, Noah's Ark atop Mount Ararat...

- ^ a b Ravenstein, E. G. (1908). Martin Behaim. His Life and his Globe. London: George Philip & Son. p. 81.

arche Noe (F 41), the Ark of Noah on a lofty mountain, the Ararat, according to the ancient legends.

- ^ Spar, Ira (2003). "The Mesopotamian Legacy: Origins of the Genesis tradition". In Aruz, Joan (ed.). Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 488. ISBN 978-1-58839-043-1. Archived from the original on 2015-11-29. Retrieved 2015-11-08.

- ^ "The Manner how the Whole Earth was Peopled by Noah & his Descendants after the Flood". British Museum. Archived from the original on December 27, 2020.

- ^ "Նոյն իջնում է Արարատից (1889) [Descent of Noah from Ararat (1889)]" (in Armenian). National Gallery of Armenia. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-11-03.

- ^ Conway Morris, Roderick (24 February 2012). "The Key to Armenia's Survival". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 March 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.