Lunar water

The search for the presence of lunar water has attracted considerable attention and motivated several recent lunar missions, largely because of water's usefulness in making long-term lunar habitation feasible.[1]

The Moon is believed to be generally anhydrous after analysis of Apollo mission soil samples. It is understood that any water vapor on the surface would generally be decomposed by sunlight, leaving hydrogen and oxygen lost to outer space. However, subsequent robotic probes found evidence of water, especially of water ice in some permanently-shadowed craters on the Moon; and in 2018 water ice was confirmed in multiple locations.[2][3][4][5] This water ice is not in the form of sheets of ice on the surface nor just under the surface, but there may be small (less than about 10 centimetres (3.9 in)) chunks of ice mixed into the regolith, and some water is chemically bonded with minerals.[6][7][8] Other experiments have detected water molecules in the negligible lunar atmosphere,[9] and even some in low concentrations at the Moon's sunlit surface.[10]

On the Moon, water (H2O) and hydroxyl group (-OH) are not present as free water but are chemically bonded within minerals as hydrates and hydroxides, existing in low concentrations across the lunar surface.[11][12] Adsorbed water is estimated to be traceable at levels of 10 to 1000 ppm.[13] The presence of water may be attributed to two primary sources: delivery over geological timescales via impacts and in situ production through interactions of solar wind hydrogen ions with oxygen-bearing minerals.[14][15] Confirmed hydroxyl-bearing materials include glasses, apatite [Ca5(PO4)3(F, Cl, OH)], and novograblenovite [(NH4)MgCl3·6H2O].

NASA's Ice-Mining Experiment-1 (set to launch on the PRIME-1 mission no earlier than late 2024) is intended to answer whether or not water ice is present in usable quantities in the southern polar region.[16]

History of observations

[edit]19th century and earlier

[edit]In the 16th century, Leonardo da Vinci in his Codex Leicester attempted to explain the luminosity of the Moon by assuming that the Moon's surface is covered by water, reflecting the Sun's light. In his model, waves on the water's surface cause the light to be reflected in many directions, explaining why the Moon is not as bright as the Sun.[17]

In 1834–1836, Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler published their four-volume Mappa Selenographica and the book Der Mond in 1837, which established the conclusion that the Moon has no bodies of water on the surface nor any appreciable atmosphere.[18]

20th century

[edit]The possibility of ice in the floors of polar lunar craters was first suggested in 1961 by Caltech researchers Kenneth Watson, Bruce C. Murray, and Harrison Brown.[19]

Earth-based radar measurements were used to identify the areas that are in permanent shadow and hence have the potential to harbour lunar ice: Estimates of the total extent of shadowed areas poleward of 87.5 degrees latitude are 1,030 and 2,550 square kilometres (400 and 980 sq mi) for the north and south poles, respectively.[20] Subsequent computer simulations encompassing additional terrain suggested that an area up to 14,000 square kilometres (5,400 sq mi) might be in permanent shadow.[21]

- Apollo Program

Although trace amounts of water were found in lunar rock samples collected by Apollo astronauts, this was assumed to be a result of contamination, and the majority of the lunar surface was generally assumed to be completely dry.[22] However, a 2008 study of lunar rock samples revealed evidence of water molecules trapped in volcanic glass beads.[23]

The first direct evidence of water vapor near the Moon was obtained by the Apollo 14 ALSEP Suprathermal Ion Detector Experiment, SIDE, on March 7, 1971. A series of bursts of water vapor ions were observed by the instrument mass spectrometer at the lunar surface near the Apollo 14 landing site.[24]

- Luna 24

On 18 August 1976, the Soviet Luna 24 probe landed at Mare Crisium, took samples from depths of 118, 143, and 184 cm of the lunar regolith, and returned them to Earth. In February 1978 Soviet scientists M. Akhmanova, B. Dement'ev, and M. Markov of the Vernadsky Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical Chemistry published a paper claiming a detection of water fairly definitively.[6][7] Their study showed that the samples returned to Earth by the 1976 Soviet probe Luna 24 contained about 0.1% water by mass, as seen in infrared absorption spectroscopy (at about 3 μm (0.00012 in) wavelength), at a detection level about 10 times above the threshold,[25] although Crotts points out that "The authors... were not willing to stake their reputations on an absolute statement that terrestrial contamination was completely avoided."[26] This would represent the first direct measurement of water content on the surface of the moon, although that result has not been confirmed by other researchers.[27]

- Clementine

A proposed evidence of water ice on the Moon came in 1994 from the United States military Clementine probe. In an investigation known as the 'bistatic radar experiment', Clementine used its transmitter to beam radio waves into the dark regions of the south pole of the Moon.[28] Echoes of these waves were detected by the large dish antennas of the Deep Space Network on Earth. The magnitude and polarisation of these echoes was consistent with an icy rather than rocky surface, but the results were inconclusive,[29] and their significance has been questioned.[30][31]

- Lunar Prospector

The Lunar Prospector probe, launched in 1998, employed a neutron spectrometer to measure the amount of hydrogen in the lunar regolith near the polar regions.[32] It was able to determine hydrogen abundance and location to within 50 parts per million and detected enhanced hydrogen concentrations at the lunar north and south poles. These were interpreted as indicating significant amounts of water ice trapped in permanently shadowed craters,[33] but could also be due to the presence of the hydroxyl radical (•OH) chemically bound to minerals. Based on data from Clementine and Lunar Prospector, NASA scientists have estimated that, if surface water ice is present, the total quantity could be of the order of 1–3 cubic kilometres (0.24–0.72 cu mi).[34][35] In July 1999, at the end of its mission, the Lunar Prospector probe was deliberately crashed into Shoemaker crater, near the Moon's south pole, in the hope that detectable quantities of water would be liberated. However, spectroscopic observations from ground-based telescopes did not reveal the spectral signature of water.[36]

- Cassini–Huygens

More suspicions about the existence of water on the Moon were generated by inconclusive data produced by Cassini–Huygens mission,[37] which passed the Moon in 1999.[citation needed]

21st century

[edit]- Deep Impact

In 2005, observations of the Moon by the Deep Impact spacecraft produced inconclusive spectroscopic data suggestive of water on the Moon. In 2006, observations with the Arecibo planetary radar showed that some of the near-polar Clementine radar returns, previously claimed to be indicative of ice, might instead be associated with rocks ejected from young craters. If true, this would indicate that the neutron results from Lunar Prospector were primarily from hydrogen in forms other than ice, such as trapped hydrogen molecules or organics. Nevertheless, the interpretation of the Arecibo data do not exclude the possibility of water ice in permanently shadowed craters.[38] In June 2009, NASA's Deep Impact spacecraft, now redesignated EPOXI, made further confirmatory bound hydrogen measurements during another lunar flyby.[22]

- Kaguya

As part of its lunar mapping programme, Japan's Kaguya probe, launched in September 2007 for a 19-month mission, carried out gamma ray spectrometry observations from orbit that can measure the abundances of various elements on the Moon's surface.[39] Japan's Kaguya probe's high resolution imaging sensors failed to detect any signs of water ice in permanently shaded craters around the south pole of the Moon,[40] and it ended its mission by crashing into the lunar surface in order to study the ejecta plume content.[41][needs update]

- Chang'e 1

The People's Republic of China's Chang'e 1 orbiter, launched in October 2007, took the first detailed photographs of some polar areas where ice water is likely to be found.[42][needs update]

- Chandrayaan-1

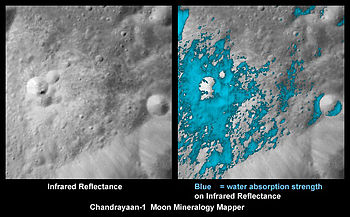

India's ISRO spacecraft Chandrayaan-1 released the Moon Impact Probe (MIP) that impacted Shackleton Crater, of the lunar south pole, at 20:31 on 14 November 2008 releasing subsurface debris that was analysed for presence of water ice. During its 25-minute descent, the impact probe's Chandra's Altitudinal Composition Explorer (CHACE) recorded evidence of water in 650 mass spectra gathered in the thin atmosphere above the Moon's surface and hydroxyl absorption lines in reflected sunlight.[43][44]

On September 25, 2009, NASA declared that data sent from its M3 confirmed the existence of hydrogen over large areas of the Moon's surface,[37] albeit in low concentrations and in the form of hydroxyl group ( · OH) chemically bound to soil.[8][45][46] This supports earlier evidence from spectrometers aboard the Deep Impact and Cassini probes.[22][47][48] On the Moon, the feature is seen as a widely distributed absorption that appears strongest at cooler high latitudes and at several fresh feldspathic craters. The general lack of correlation of this feature in sunlit M3 data with neutron spectrometer H abundance data suggests that the formation and retention of OH and H2O is an ongoing surficial process. OH/H2O production processes may feed polar cold traps and make the lunar regolith a candidate source of volatiles for human exploration.[citation needed]

Although M3 results are consistent with recent findings of other NASA instruments onboard Chandrayaan-1, the discovered water molecules in the Moon's polar regions is not consistent with the presence of thick deposits of nearly pure water ice within a few meters of the lunar surface, but it does not rule out the presence of small (<~10 cm (3.9 in)), discrete pieces of ice mixed in with the regolith.[49] Additional analysis with M3 published in 2018 had provided more direct evidence of water ice near the surface within 20° latitude of both poles. In addition to observing reflected light from the surface, scientists used M3's near-infrared absorption capabilities in the permanently shadowed areas of the polar regions to find absorption spectra consistent with ice. At the north pole region, the water ice is scattered in patches, while it is more concentrated in a single body around the south pole. Because these polar regions do not experience the high temperatures (greater than 373 Kelvin), it was postulated that the poles act as cold traps where vaporized water is collected on the Moon.[50][51]

In March 2010, it was reported that the Mini-SAR on board Chandrayaan-1 had discovered more than 40 permanently darkened craters near the Moon's north pole that are hypothesized to contain an estimated 600 million metric tonnes of water-ice.[52][53] The radar's high CPR is not uniquely diagnostic of either roughness or ice; the science team must take into account the environment of the occurrences of high CPR signal to interpret its cause. The ice must be relatively pure and at least a couple of meters thick to give this signature.[53] The estimated amount of water ice potentially present is comparable to the quantity estimated from the previous mission of Lunar Prospector's neutron data.[53]

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter | Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite

On October 9, 2009, the Centaur upper stage of its Atlas V carrier rocket was directed to impact Cabeus crater at 11:31 UTC, followed shortly by the NASA's Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) spacecraft that flew through the ejecta plume.[54] LCROSS detected a significant amount of hydroxyl group in the material thrown up from a south polar crater by an impactor;[55][56] this may be attributed to water-bearing materials – what appears to be "near pure crystalline water-ice" mixed in the regolith.[52][56][57] What was actually detected was the chemical group hydroxyl ( · OH), which is suspected to be from water,[11] but could also be hydrates, which are inorganic salts containing chemically bound water molecules. The nature, concentration and distribution of this material requires further analysis;[56] chief mission scientist Anthony Colaprete has stated that the ejecta appears to include a range of fine-grained particulates of near pure crystalline water-ice.[52] A later definitive analysis found the concentration of water to be "5.6 ± 2.9% by mass".[58]

The Mini-RF instrument on board the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) observed the plume of debris from the impact of the LCROSS orbiter, and it was concluded that the water ice must be in the form of small (< ~10 cm), discrete pieces of ice distributed throughout the regolith, or as thin coating on ice grains.[59] This, coupled with monostatic radar observations, suggest that the water ice present in the permanently shadowed regions of lunar polar craters is unlikely to be present in the form of thick, pure ice deposits.[59][60][61]

The data acquired by the Lunar Exploration Neutron Detector (LEND) instrument onboard LRO show several regions where the epithermal neutron flux from the surface is suppressed, which is indicative of enhanced hydrogen content.[62] Further analysis of LEND data suggests that water content in the polar regions is not directly determined by the illumination conditions of the surface, as illuminated and shadowed regions do not manifest any significant difference in the estimated water content.[63] According to the observations by this instrument alone, "the permanent low surface temperature of the cold traps is not a necessary and sufficient condition for enhancement of water content in the regolith."[63]

LRO laser altimeter's examination of the Shackleton crater at the lunar south pole suggests up to 22% of the surface of that crater is covered in ice.[64]

- Melt inclusions in Apollo 17 samples

In May 2011, Erik Hauri et al. reported[65] 615-1410 ppm water in melt inclusions in lunar sample 74220, the famous high-titanium "orange glass soil" of volcanic origin collected during the Apollo 17 mission in 1972. The inclusions were formed during explosive eruptions on the Moon approximately 3.7 billion years ago.[citation needed]

This concentration is comparable with that of magma in Earth's upper mantle. While of considerable selenological interest, this announcement affords little comfort to would-be lunar colonists. The sample originated many kilometers below the surface, and the inclusions are so difficult to access that it took 39 years to detect them with a state-of-the-art ion microprobe instrument.[citation needed]

- Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy

In October 2020, astronomers reported detecting molecular water on the sunlit surface of the Moon by several independent scientific teams, including the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).[66][67] The estimated abundance is about 100 to 400 ppm, with a distribution over a small latitude range, likely a result of local geology and not a global phenomenon. It was suggested that the detected water is stored within glasses or in voids between grains sheltered from the harsh lunar environment, thus allowing the water to remain on the lunar surface.[68] Using data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, it was shown that besides the large, permanently shadowed regions in the Moon's polar regions, there are many unmapped cold traps, substantially augmenting the areas where ice may accumulate. Approximately 10–20% of the permanent cold-trap area for water is found to be contained in "micro cold traps" found in shadows on scales from 1 km to 1 cm, for a total area of ~40,000 km2, about 60% of which is in the South, and a majority of cold traps for water ice are found at latitudes >80° due to permanent shadows.[69]

October 26, 2020: In a paper published in Nature Astronomy, a team of scientists used SOFIA, an infrared telescope mounted inside a 747 jumbo jet, to make observations that showed unambiguous evidence of water on parts of the Moon where the sun shines. "This discovery reveals that water might be distributed across the lunar surface and not limited to the cold shadowed places near the lunar poles," Paul Hertz, the director of NASA's astrophysics division, said.[70]

- Lunar IceCube

Lunar IceCube is a 6U (six unit) CubeSat that was to estimate amount and composition of lunar ice, using an infrared imaging spectrometer developed by NASAs Goddard Space Flight Center.[71] The spacecraft separated from Artemis 1 successfully on November 17, 2022, but failed to communicate shortly thereafter[72] and is presumed lost.

- PRIME-1

A dedicated on-site experiment by NASA dubbed PRIME-1 is slated to land on the Moon no earlier than November, 2023 near Shackleton Crater at the Lunar South Pole. The mission will drill for water ice.[73][74]

- Lunar Trailblazer

Slated to launch as a ride-along mission in 2025, the Lunar Trailblazer satellite is part of NASA's Small Innovative Missions for Planetary Exploration (SIMPLEx) program.[75] The satellite carries two instruments—a high-resolution spectrometer, which will detect and map different forms of water, and a thermal mapper. The mission's primary objectives are to characterize the form of lunar water, how much is present and where; determine how lunar volatiles change and move over time; measure how much and what form of water exists in permanently shadowed regions of the Moon; and to assess how differences in the reflectivity and temperature of lunar surfaces affect the concentration of lunar water.[76]

Chang'e-5 probe

Chang'e 5 measurements on 117 individual spherical glass beads reveal 0–1,909 μg/g of H20, equivalent to 2.7E14 kg of trapped water on the lunar surface pointing to a new mechanism for storing water on the lunar surface. The findings could be useful for future lunar missions by identifying glasses as a potential resources that could be converted to drinking water or rocket fuel.[77][78] Another unusual hdyroxl-bearing mineral was discovered in the Chang'e 5 regolith novograblenovite (NH4)MgCl3·6H2O.[79] On Earth, this mineral has been identified around fumaroles and hydrothermal activity.

Possible water cycle

[edit]Composition and Volatile-Bearing Materials

[edit]- Meteoritic Input

The composition of lunar water is not yet fully understood and is primarily inferred through remote sensing techniques. The lunar surface, is significantly shaped by meteoritic impacts and likely contains a range of minerals that could harbor hydroxyls. These include hydrated and sulfur-bearing minerals such as epsomite, blödite, gypsum/bassanite, and jarosite. Lunar water may not be pure; instead, it could potentially be a brine, water with dissolved salts and other volatiles. These brines could form from or coexist with minerals delivered by carbonaceous chondrites and CI/CM chondrites, which bring hydrous minerals and potentially soluble compounds to the Moon. Micrometeorites and interplanetary dust particles contribute additional volatile compounds such as H2O, CO, and possibly CO2 and impact the lunar surface with a flux of 1/1m² per day.[80] Furthermore, the potential presence of subsurface brines on larger celestial bodies like Ceres highlights the possibility of similar ices on the Moon.[81]

- Observations

Data from the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) confirmed a variety of volatiles in the lunar regolith including water (H2O), hydrogen (H2), carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), ammonia (NH3), sulfur dioxide (SO2), ethylene (C2H4), carbon dioxide (CO2), methanol (CH3OH), mercury (Hg), and methane (CH4).[82]

- Confirmed Materials

Confirmed hydroxyl-bearing lunar materials include glasses, apatite, and novograblenovite (NH4)MgCl3·6H2O.[83]

Production

[edit]Lunar water has several potential origins: the Earth, water-bearing comets (and other bodies) striking the Moon, and in situ production.[84][85] It has been theorized that the latter may occur when hydrogen ions (protons) in the solar wind chemically combine with the oxygen atoms present in the lunar minerals (oxides, silicates, etc.) to produce small amounts of water trapped in the minerals' crystal lattices or as hydroxyl groups, potential water precursors.[86] (This mineral-bound water, or mineral surface, must not be confused with water ice.)

The hydroxyl surface groups (X–OH) formed by the reaction of protons (H+) with oxygen atoms accessible at oxide surface (X=O) could further be converted in water molecules (H2O) adsorbed onto the oxide mineral's surface. The mass balance of a chemical rearrangement supposed at the oxide surface could be schematically written as follows:

- 2 X–OH → X=O + X + H2O

or,

- 2 X–OH → X–O–X + H2O

where "X" represents the oxide surface.

The formation of one water molecule requires the presence of two adjacent hydroxyl groups or a cascade of successive reactions of one oxygen atom with two protons. This could constitute a limiting factor and decreases the probability of water production if the proton density per surface unit is too low.[citation needed]

Trapping

[edit]Solar radiation would normally strip any free water or water ice from the lunar surface, splitting it into its constituent elements, hydrogen and oxygen, which then escape to space. However, because of the only very slight axial tilt of the Moon's spin axis to the ecliptic plane (1.5 °), some deep craters near the poles never receive any sunlight, and are permanently shadowed (see, for example, Shackleton crater, and Whipple crater). The temperature in these regions never rises above about 100 K (about −170 ° Celsius),[87] and any water that eventually ended up in these craters could remain frozen and stable for extremely long periods of time — perhaps billions of years, depending on the stability of the orientation of the Moon's axis.[23][29]

While the ice deposits may be thick, they are most likely mixed with the regolith, possibly in a layered formation.[88]

Impact glass beads could store and release water, possibly storing as much as 270 billion tonnes of water.[89]

Transport

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Although free water cannot persist in illuminated regions of the Moon, any such water produced there by the action of the solar wind on lunar minerals might, through a process of evaporation and condensation,[dubious – discuss] migrate to permanently cold polar areas and accumulate there as ice, perhaps in addition to any ice brought by comet impacts.[22]

The hypothetical mechanism of water transport / trapping (if any) remains unknown: indeed lunar surfaces directly exposed to the solar wind where water production occurs are too hot to allow trapping by water condensation (and solar radiation also continuously decomposes water), while no (or much less) water production is expected in the cold areas not directly exposed to the Sun. Given the expected short lifetime of water molecules in illuminated regions, a short transport distance would in principle increase the probability of trapping. In other words, water molecules produced close to a cold, dark polar crater should have the highest probability of surviving and being trapped.

To what extent, and at what spatial scale, direct proton exchange (protolysis) and proton surface diffusion directly occurring at the naked surface of oxyhydroxide minerals exposed to space vacuum (see surface diffusion and self-ionization of water) could also play a role in the mechanism of the water transfer towards the coldest point is presently unknown and remains a conjecture.

Simulations of lunar thermal conditions show that diurnal temperature variations could drive centimeter-scale water migration and accumulation in the Moon's subsurface.[90]

LADEE data shows that the shock waves from impact events cause water beneath the surface to evaporate.[91]

Liquid water

[edit]4–3.5 billion years ago, the Moon could have had sufficient atmosphere and liquid water on its surface.[92][93] Isotope analysis of water in lunar samples suggests that some lunar water originates from Earth, possibly due to the Giant Impact event.[85]

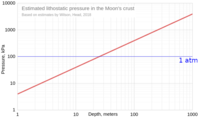

Warm and pressurized regions in the Moon's interior might still contain liquid water.[94] Underground lakes of liquid water on the Moon require a reservoir of underground water, a source of heat, and a barrier sufficient to stop the water from being lost to space. Subsurface ice layers may block the diffusion of deeper liquid water, so subterranean "lakes" could be present underneath a region with surface or subsurface ice.[95]

Uses

[edit]The presence of large quantities of water on the Moon would be an important factor in rendering lunar habitation cost-effective since transporting water (or hydrogen and oxygen) from Earth would be prohibitively expensive. If future investigations find the quantities to be particularly large, water ice could be mined to provide liquid water for drinking and plant propagation, and the water could also be split into hydrogen and oxygen by solar panel-equipped electric power stations or a nuclear generator, providing breathable oxygen as well as the components of rocket fuel. The hydrogen component of the water ice could also be used to draw out the oxides in the lunar soil and harvest even more oxygen. Analysis of lunar ice would also provide scientific information about the impact history of the Moon and the abundance of comets and asteroids in the early Inner Solar System.[96]

Ownership

[edit]The hypothetical discovery of usable quantities of water on the Moon may raise legal questions about who owns the water and who has the right to exploit it. The United Nations Outer Space Treaty does not prevent the exploitation of lunar resources, but does prevent the appropriation of the Moon by individual nations and is generally interpreted as barring countries from claiming ownership of Lunar resources.[97][98] However most legal experts agree that the ultimate test of the question will arise through precedents of national or private activity.[citation needed]

The Moon Treaty specifically stipulates that exploitation of lunar resources is to be governed by an "international regime", but that treaty has only been ratified by a few nations, and primarily those with no independent spaceflight capabilities.[99]

Luxembourg[100] and the US[101][102][103] have granted their citizens the right to mine and own space resources, including the resources of the Moon. US President Donald Trump expressly stated that in his executive order of 6 April 2020.[103]

See also

[edit]- Missions mapping lunar water

- Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter

- Chandrayaan-2 lunar orbiter and rover

- Lunar Flashlight solar sail orbiter

- Lunar IceCube lunar orbiter

- LunaH-Map lunar obiter

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

References

[edit]- ^ "The Moon". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. Retrieved 2022-07-07.

- ^ Water and Ices on the Moon", science.nasa.gov, fetched 11 June 2024

- ^ "Ice Confirmed at the Moon's Poles". NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL). Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ Water on the Moon: Direct evidence from Chandrayaan-1's Moon Impact Probe. Published on 2010/04/07.

- ^ Pinson, Jerald (2020-11-20). "Moon May Hold Billions of Tons of Subterranean Ice at Its Poles". Eos. 101. doi:10.1029/2020eo151889.

- ^ a b Akhmanova, M; Dement'ev, B; Markov, M (February 1978). "Water in the regolith of Mare Crisium (Luna-24)?". Geokhimiya (in Russian) (285).

- ^ a b Akhmanova, M; Dement'ev, B; Markov, M (1978). "Possible Water in Luna 24 Regolith from the Sea of Crises". Geochemistry International. 15 (166).

- ^ a b Pieters, C. M.; Goswami, J. N.; Clark, R. N.; Annadurai, M.; Boardman, J.; Buratti, B.; Combe, J. -P.; Dyar, M. D.; Green, R.; Head, J. W.; Hibbitts, C.; Hicks, M.; Isaacson, P.; Klima, R.; Kramer, G.; Kumar, S.; Livo, E.; Lundeen, S.; Malaret, E.; McCord, T.; Mustard, J.; Nettles, J.; Petro, N.; Runyon, C.; Staid, M.; Sunshine, J.; Taylor, L. A.; Tompkins, S.; Varanasi, P. (2009). "Character and Spatial Distribution of OH/H2O on the Surface of the Moon Seen by M3 on Chandrayaan-1". Science. 326 (5952): 568–572. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..568P. doi:10.1126/science.1178658. PMID 19779151.

- ^ "Is There an Atmosphere on the Moon? | NASA". nasa.gov. 7 June 2013. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- ^ "NASA - SOFIA discovers water on sunlit surface of the Moon". NASA. 26 October 2020.

- ^ a b Lucey, Paul G. (23 October 2009). "A Lunar Waterworld". Science. 326 (5952): 531–532. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..531L. doi:10.1126/science.1181471. PMID 19779147.

- ^ "NASA's SOFIA Discovers Water on Sunlit Surface of Moon". NASA. 26 October 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Clark, Roger N. (23 October 2009). "Detection of Adsorbed Water and Hydroxyl on the Moon". Science. 326 (5952): 562–564. Bibcode:2009Sci...326..562C. doi:10.1126/science.1178105. PMID 19779152.

- ^ Elston, D.P. (1968) "Character and Geologic Habitat of Potential Deposits of Water, Carbon and Rare Gases on the Moon", Geological Problems in Lunar and Planetary Research, Proceedings of AAS/IAP Symposium, AAS Science and Technology Series, Supplement to Advances in the Astronautical Sciences., p. 441

- ^ "NASA – Lunar Prospector". lunar.arc.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2015-05-25.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details".

- ^ "An introduction to Leonardo da Vinci's Codices Arundel and Leicester" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- ^ Erich Robens; Stanislaw Halas (16 February 2009). "Study on the Possible Existence of Water on the Moon" (PDF). Geochronometria. 33 (–1): 23–31. Bibcode:2009Gchrm..33...23R. doi:10.2478/v10003-009-0008-2. Retrieved April 9, 2023.

- ^ Watson, Kenneth; Murray, Bruce C.; Brown, Harrison (September 1961). "The behavior of volatiles on the lunar surface". Journal of Geophysical Research. 66 (9): 3033–3045. Bibcode:1961JGR....66.3033W. doi:10.1029/jz066i009p03033.

- ^ Margot, J. L. (1999). "Topography of the Lunar Poles from Radar Interferometry: A Survey of Cold Trap Locations". Science. 284 (5420): 1658–1660. Bibcode:1999Sci...284.1658M. doi:10.1126/science.284.5420.1658. PMID 10356393.

- ^ Linda, Martel (June 4, 2003). "The Moon's Dark, Icy Poles".

- ^ a b c d "It's Official: Water Found on the Moon", Space.com, 23 September 2009

- ^ a b Minkel, J. R. (9 July 2008). "Moon Once Harbored Water, Lunar Lava Beads Show". Scientific American.

- ^ Freeman, J. W.; Hills, H. K.; Lindeman, R. A.; Vondrak, R. R. (March 1973). "Observations of water vapor ions at the lunar surface". The Moon. 8 (1): 115–128. Bibcode:1973Moon....8..115F. doi:10.1007/BF00562753.

- ^ Crotts, Arlin (2012). "Water on The Moon, I. Historical Overview". arXiv:1205.5597v1 [astro-ph.EP].

- ^ Crotts, Arlin (October 12, 2009). "Water on the Moon", The Space Review. Retrieved 13 November 2023

- ^ Spudis, Paul D. (June 1, 2012). "Who discovered water on the Moon?", Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ Nozette, S.; Lichtenberg, C. L.; Spudis, P.; Bonner, R.; Ort, W.; Malaret, E.; Robinson, M.; Shoemaker, E. M. (29 November 1996). "The Clementine Bistatic Radar Experiment". Science. 274 (5292): 1495–1498. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1495N. doi:10.1126/science.274.5292.1495. hdl:2060/19970023672. PMID 8929403.

- ^ a b Clementine Probe Archived July 24, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Simpson, Richard A.; Tyler, G. Leonard (1999). "Reanalysis of Clementine bistatic radar data from the lunar South Pole". Journal of Geophysical Research. 104 (E2): 3845. Bibcode:1999JGR...104.3845S. doi:10.1029/1998JE900038. hdl:2060/19990047963.

- ^ Campbell, Donald B.; Campbell, Bruce A.; Carter, Lynn M.; Margot, Jean-Luc; Stacy, Nicholas J. S. (2006). "No evidence for thick deposits of ice at the lunar south pole" (PDF). Nature. 443 (7113): 835–7. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..835C. doi:10.1038/nature05167. PMID 17051213.

- ^ "Eureka! Ice found at lunar poles". August 31, 2001. Archived from the original on December 9, 2006.

- ^ Lunar Prospector Science Results NASA

- ^ Prospecting for Lunar Water Archived 2010-03-18 at the Wayback Machine, NASA

- ^ Neutron spectrometer results Archived January 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ No water ice detected from Lunar Prospector, NASA website

- ^ a b Kemm, Kelvin (October 9, 2009). "Evidence of water on the Moon, Mars alters planning for manned bases". Engineering News. Retrieved 2009-10-09.

- ^ Paul Spudis (2006). "Ice on the Moon". The Space Review. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ Kaguya Gamma Ray Spectrometer, JAXA

- ^ "Japan's now-finished lunar mission found no water ice". Spaceflight Now. July 6, 2009. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ "Japanese probe crashes into Moon". BBC News. 2009-06-11. Retrieved 2013-09-27.

- ^ "Who's Orbiting the Moon?" Archived 2010-02-21 at the Wayback Machine, NASA, February 20, 2008

- ^ "Chandrayaan team over the Moon". The Hindu. 2008-11-15. Archived from the original on 2008-12-16.

- ^ "MIP detected water on Moon way back in June: ISRO Chairman". The Hindu. 2009-09-25.

- ^ "Spacecraft see 'damp' Moon soils", BBC, 24 September 2009

- ^ Leopold, George (2009-11-13). "NASA confirms water on Moon". Retrieved 2009-11-18.

- ^ "Moon crash will create six-mile plume of dust as Nasa searches for water", The Times, October 3, 2009

- ^ Discovery of water on Moon boosts prospects for permanent lunar base, The Guardian, 24 September 2009

- ^ Neish, C. D.; D. B. J. Bussey; P. Spudis; W. Marshall; B. J. Thomson; G. W. Patterson; L. M. Carter. (13 January 2011). "The nature of lunar volatiles as revealed by Mini-RF observations of the LCROSS impact site". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 116 (E01005): 8. Bibcode:2011JGRE..116.1005N. doi:10.1029/2010JE003647. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

the Mini-RF instruments on ISRO's Chandrayaan-1 and NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) obtained S band (12.6 cm (5.0 in)) synthetic aperture radar images of the impact site at 150 and 30 m resolution, respectively. These observations show that the floor of Cabeus has a circular polarization ratio (CPR) comparable to or less than the average of nearby terrain in the southern lunar highlands. Furthermore, <2% of the pixels in Cabeus crater have CPR values greater than unity. This observation is not consistent with the presence of thick deposits of nearly pure water ice within a few meters of the lunar surface, but it does not rule out the presence of small (<~10 cm (3.9 in)), discrete pieces of ice mixed in with the regolith.

- ^ Rincon, Paul (21 August 2018). "Water ice 'detected on Moon's surface'". BBC. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Shuai Li; Paul G. Lucey; Ralph E. Milliken; Paul O. Hayne; Elizabeth Fisher; Jean-Pierre Williams; Dana M. Hurley; Richard C. Elphic (20 August 2018). "Direct evidence of surface exposed water ice in the lunar polar regions". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 115 (36): 8907–8912. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.8907L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1802345115. PMC 6130389. PMID 30126996.

- ^ a b c "Ice deposits found at Moon's pole". BBC News, 2 March 2010.

- ^ a b c "NASA Radar Finds Ice Deposits at Moon's North Pole". NASA. March 2010. Retrieved 2012-03-26.

- ^ LCROSS mission overview Archived 2009-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, NASA

- ^ Lakdawalla, Emily (13 November 2009). "LCROSS Lunar Impactor Mission: "Yes, We Found Water!"". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 22 January 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-13.

- ^ a b c Dino, Jonas; Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite Team (November 13, 2009). "LCROSS Impact Data Indicates Water on Moon". NASA. Retrieved 2009-11-14.

- ^ Moon River: What Water in the Heavens Means for Life on Earth, by Randall Amster, The Huffington Post, November 30, 2009.

- ^ Colaprete, Anthony; Schultz, Peter; Heldmann, Jennifer; Wooden, Diane; Shirley, Mark; Ennico, Kimberly; Hermalyn, Brendan; Marshall, William; Ricco, Antonio; Elphic, Richard C.; Goldstein, David; Summy, Dustin; Bart, Gwendolyn D.; Asphaug, Erik; Korycansky, Don; Landis, David; Sollitt, Luke (22 October 2010). "Detection of Water in the LCROSS Ejecta Plume". Science. 330 (6003): 463–468. Bibcode:2010Sci...330..463C. doi:10.1126/science.1186986. PMID 20966242.

- ^ a b Jozwiak, L. M.; Patterson, G. W.; Perkins, R. (July 2019). Mini-RF Monostatic Radar Observations of Permanently Shadowed Crater Floors. Lunar ISRU 2019 - Developing a New Space Economy Through Lunar Resources and Their Utilization. Vol. 2152. p. 5079. Bibcode:2019LPICo2152.5079J.

- ^ Nozette, Stewart; Spudis, Paul; Bussey, Ben; Jensen, Robert; Raney, Keith; Winters, Helene; Lichtenberg, Christopher L.; Marinelli, William; Crusan, Jason; Gates, Michele; Robinson, Mark (January 2010). "The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Miniature Radio Frequency (Mini-RF) Technology Demonstration". Space Science Reviews. 150 (1–4): 285–302. Bibcode:2010SSRv..150..285N. doi:10.1007/s11214-009-9607-5.

- ^ Neish, C. D.; Bussey, D. B. J.; Spudis, P.; Marshall, W.; Thomson, B. J.; Patterson, G. W.; Carter, L. M. (13 January 2011). "The nature of lunar volatiles as revealed by Mini-RF observations of the LCROSS impact site". Journal of Geophysical Research. 116 (E1). Bibcode:2011JGRE..116.1005N. doi:10.1029/2010JE003647.

- ^ Mitrofanov, I. G.; Sanin, A. B.; Boynton, W. V.; Chin, G.; Garvin, J. B.; Golovin, D.; Evans, L. G.; Harshman, K.; Kozyrev, A. S.; Litvak, M. L.; Malakhov, A.; Mazarico, E.; McClanahan, T.; Milikh, G.; Mokrousov, M.; Nandikotkur, G.; Neumann, G. A.; Nuzhdin, I.; Sagdeev, R.; Shevchenko, V.; Shvetsov, V.; Smith, D. E.; Starr, R.; Tretyakov, V. I.; Trombka, J.; Usikov, D.; Varenikov, A.; Vostrukhin, A.; Zuber, M. T. (2010). "Hydrogen Mapping of the Lunar South Pole Using the LRO Neutron Detector Experiment LEND". Science. 330 (6003): 483–486. Bibcode:2010Sci...330..483M. doi:10.1126/science.1185696. PMID 20966247.

- ^ a b Mitrofanov, I. G.; Sanin, A. B.; Litvak, M. L. (February 2016). "Water in the Moon's polar areas: Results of LEND neutron telescope mapping". Doklady Physics. 61 (2): 98–101. Bibcode:2016DokPh..61...98M. doi:10.1134/S1028335816020117.

- ^ Researchers Estimate Ice Content of Crater at Moon's South Pole (NASA)

- ^ Hauri, Erik H.; Weinreich, Thomas; Saal, Alberto E.; Rutherford, Malcolm C.; Van Orman, James A. (8 July 2011). "High Pre-Eruptive Water Contents Preserved in Lunar Melt Inclusions". Science. 333 (6039): 213–215. Bibcode:2011Sci...333..213H. doi:10.1126/science.1204626. PMID 21617039.

- ^ Guarino, Ben; Achenbach, Joel (26 October 2020). "Pair of studies confirm there is water on the moon - New research confirms what scientists had theorized for years — the moon is wet". The Washington Post. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (26 October 2020). "There's Water and Ice on the Moon, and in More Places Than NASA Once Thought - Future astronauts seeking water on the moon may not need to go into the most treacherous craters in its polar regions to find it". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- ^ Honniball, C. I.; Lucey, P. G.; Li, S.; Shenoy, S.; Orlando, T. M.; Hibbitts, C. A.; Hurley, D. M.; Farrell, W. M. (26 October 2020). "Molecular water detected on the sunlit Moon by SOFIA". Nature Astronomy. 5 (2): 121–127. Bibcode:2021NatAs...5..121H. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-01222-x.

- ^ Hayne, P. O.; Aharonson, O.; Schörghofer, N. (26 October 2020). "Micro cold traps on the Moon". Nature Astronomy. 5 (2): 169–175. arXiv:2005.05369. Bibcode:2021NatAs...5..169H. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-1198-9.

- ^ "NASA's SOFIA Discovers Water on Sunlit Surface of Moon". NASA (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 26 October 2020.

- ^ "NASA - Lunar IceCube to Take on Big Mission from Small Package". 4 August 2015.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (2023-02-17). "Deep space smallsats face big challenges". SpaceNews. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "NASA, Intuitive Machines Announce Landing Site for Lunar Drill". 3 November 2021.

- ^ "NASA - NSSDCA - Spacecraft - Details".

- ^ "JPL Science: Lunar Trailblazer". JPL Science. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "Lunar Discovery and Exploration Program (LDEP)". NASA Science. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ Tereza Pultarova (2023-03-28). "Hidden water source on the moon found locked in glass beads, Chinese probe reveals". Space.com. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ He, Huicun; Ji, Jianglong; Zhang, Yue; Hu, Sen; Lin, Yangting; Hui, Hejiu; Hao, Jialong; Li, Ruiying; Yang, Wei; Tian, Hengci; Zhang, Chi; Anand, Mahesh; Tartèse, Romain; Gu, Lixin; Li, Jinhua (April 2023). "A solar wind-derived water reservoir on the Moon hosted by impact glass beads". Nature Geoscience. 16 (4): 294–300. Bibcode:2023NatGe..16..294H. doi:10.1038/s41561-023-01159-6.

- ^ Jin, Shifeng; Hao, Munan; Guo, Zhongnan; Yin, Bohao; Ma, Yuxin; Deng, Lijun; Chen, Xu; Song, Yanpeng; Cao, Cheng; Chai, Congcong; Wei, Qi; Ma, Yunqi; Guo, Jiangang; Chen, Xiaolong (16 July 2024). "Evidence of a hydrated mineral enriched in water and ammonium molecules in the Chang'e-5 lunar sample". Nature Astronomy. 8 (9): 1127–1137. arXiv:2305.05263. Bibcode:2024NatAs...8.1127J. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02306-8.

- ^ Denevi, Brett W.; Noble, Sarah K.; Christoffersen, Roy; Thompson, Michelle S.; Glotch, Timothy D.; Blewett, David T.; Garrick-Bethell, Ian; Gillis-Davis, Jeffrey J.; Greenhagen, Benjamin T.; Hendrix, Amanda R.; Hurley, Dana M.; Keller, Lindsay P.; Kramer, Georgiana Y.; Trang, David (December 2023). "Space Weathering At The Moon". Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry. 89 (1): 611–650. Bibcode:2023RvMG...89..611D. doi:10.2138/rmg.2023.89.14.

- ^ "Mystery Solved: Bright Areas on Ceres Come From Salty Water Below". NASA (Press release). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 10 August 2020.

- ^ Colaprete, Anthony; Schultz, Peter; Heldmann, Jennifer; Wooden, Diane; Shirley, Mark; Ennico, Kimberly; Hermalyn, Brendan; Marshall, William; Ricco, Antonio; Elphic, Richard C.; Goldstein, David; Summy, Dustin; Bart, Gwendolyn D.; Asphaug, Erik; Korycansky, Don; Landis, David; Sollitt, Luke (22 October 2010). "Detection of Water in the LCROSS Ejecta Plume". Science. 330 (6003): 463–468. Bibcode:2010Sci...330..463C. doi:10.1126/science.1186986. PMID 20966242.

- ^ Jin, Shifeng; Hao, Munan; Guo, Zhongnan; Yin, Bohao; Ma, Yuxin; Deng, Lijun; Chen, Xu; Song, Yanpeng; Cao, Cheng; Chai, Congcong; Wei, Qi; Ma, Yunqi; Guo, Jiangang; Chen, Xiaolong (16 July 2024). "Evidence of a hydrated mineral enriched in water and ammonium molecules in the Chang'e-5 lunar sample". Nature Astronomy. 8 (9): 1127–1137. arXiv:2305.05263. Bibcode:2024NatAs...8.1127J. doi:10.1038/s41550-024-02306-8.

- ^ "Your Guide to Water on the Moon".

- ^ a b Robinson, Katharine L.; Barnes, Jessica J.; Nagashima, Kazuhide; Thomen, Aurélien; Franchi, Ian A.; Huss, Gary R.; Anand, Mahesh; Taylor, G. Jeffrey (September 2016). "Water in evolved lunar rocks: Evidence for multiple reservoirs" (PDF). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 188: 244–260. Bibcode:2016GeCoA.188..244R. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2016.05.030.

- ^ Teodoro, L. F. A.; Eke, V. R.; Elphic, R. (November 2009). Lunar Hydrogen Distribution After Kaguya (SELENE) (PDF). Annual Meeting of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group. Vol. 1515. p. 70. Bibcode:2009LPICo1515...70T.

- ^ Ice on the Moon, NASA

- ^ The Moon and Mercury May Have Thick Ice Deposits. Bill Steigerwald and Nancy Jones, NASA. 2 August 2019.

- ^ Griffin, Andrew (2023-03-27). "Scientists find 'reservoir' on the Moon". The Independent. Retrieved 2024-09-14.

- ^ Reiss, P.; Warren, T.; Sefton-Nash, E.; Trautner, R. (May 2021). "Dynamics of Subsurface Migration of Water on the Moon". Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets. 126 (5). Bibcode:2021JGRE..12606742R. doi:10.1029/2020JE006742.

- ^ "There is water just under the surface of the moon that we could use".

- ^ "Mysteries from the moon's past". Washington State University. 23 July 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Schulze-Makuch, Dirk; Crawford, Ian A. (2018). "Was There an Early Habitability Window for Earth's Moon?". Astrobiology. 18 (8): 985–988. Bibcode:2018AsBio..18..985S. doi:10.1089/ast.2018.1844. PMC 6225594. PMID 30035616.

- ^ "News | Center for Astrophysics".

- ^ Eubanks, Marshall; Blase, William; Lingam, Manasvi; Hein, Andreas (2022). Subterranean Lakes on the Moon: Liquid Water Beneath the Ice. 2022 NASA Exploration Science Forum.

- ^ "Your Guide to Water on the Moon".

- ^ Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies ("Outer Space Treaty") Archived 2011-04-27 at the Wayback Machine, UN Office for Outer Space Affairs

- ^ "Moon Water: A Trickle of Data and a Flood of Questions", space.com, March 6, 2006

- ^ Agreement Governing the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies ("Moon Treaty") Archived 2008-05-14 at the Wayback Machine, UN Office for Outer Space Affairs

- ^ "Luxembourg leads the trillion-dollar race to become the Silicon Valley of asteroid mining". CNBC. 16 April 2018.

- ^ "The House just passed a bill about space mining. The future is here". The Washington Post. 2015-05-22.

- ^ "It's now legal to own and mine asteroids". The Independent. 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2023-04-13.

- ^ a b "White House looks for international support for space resource rights". 7 April 2020.

External links

[edit]- CubeSat for investigating ice on the Moon — SPIE Newsroom

- Ice on the Moon — NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

- Fluxes of fast and epithermal neutrons from Lunar Prospector: Evidence for water ice at the lunar poles — Science

- Moon has a litre of water for every tonne of soil — Times Online

- Unambiguous evidence of water on the Moon — Slashdot Science Story