Monetarism

| Part of a series on |

| Macroeconomics |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of policy-makers in controlling the amount of money in circulation. It gained prominence in the 1970s but was mostly abandoned as a direct guidance to monetary policy during the following decade because of the rise of inflation targeting through movements of the official interest rate.

The monetarist theory states that variations in the money supply have major influences on national output in the short run and on price levels over longer periods. Monetarists assert that the objectives of monetary policy are best met by targeting the growth rate of the money supply rather than by engaging in discretionary monetary policy.[1] Monetarism is commonly associated with neoliberalism.[2]

Monetarism is mainly associated with the work of Milton Friedman, who was an influential opponent of Keynesian economics, criticising Keynes's theory of fighting economic downturns using fiscal policy (e.g. government spending). Friedman and Anna Schwartz wrote an influential book, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, and argued that inflation is "always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon".[3]

Although opposed to the existence of the Federal Reserve,[4] Friedman advocated, given its existence, a central bank policy aimed at keeping the growth of the money supply at a rate commensurate with the growth in productivity and demand for goods. Money growth targeting was mostly abandoned by the central banks who tried it, however. Contrary to monetarist thinking, the relation between money growth and inflation proved to be far from tight. Instead, starting in the early 1990s, most major central banks turned to direct inflation targeting, relying on steering short-run interest rates as their main policy instrument.[5]: 483–485 Afterwards, monetarism was subsumed into the new neoclassical synthesis which appeared in macroeconomics around 2000.

Description

[edit]Monetarism is an economic theory that focuses on the macroeconomic effects of the supply of money and central banking. Formulated by Milton Friedman, it argues that excessive expansion of the money supply is inherently inflationary, and that monetary authorities should focus solely on maintaining price stability.

Monetarist theory draws its roots from the quantity theory of money, a centuries-old economic theory which had been put forward by various economists, among them Irving Fisher and Alfred Marshall, before Friedman restated it in 1956.[6][7]

Monetary history of the United States

[edit]

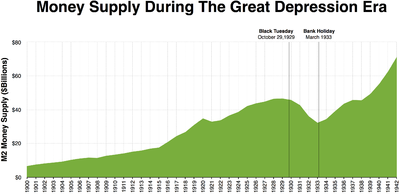

Monetarists argued that central banks sometimes caused major unexpected fluctuations in the money supply. Friedman asserted that actively trying to stabilize demand through monetary policy changes can have negative unintended consequences.[5]: 511–512 In part he based this view on the historical analysis of monetary policy, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960, which he coauthored with Anna Schwartz in 1963. The book attributed inflation to excess money supply generated by a central bank. It attributed deflationary spirals to the reverse effect of a failure of a central bank to support the money supply during a liquidity crunch.[8] In particular, the authors argued that the Great Depression of the 1930s was caused by a massive contraction of the money supply (they deemed it "the Great Contraction"[9]), and not by the lack of investment that Keynes had argued. They also maintained that post-war inflation was caused by an over-expansion of the money supply. They made famous the assertion of monetarism that "inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon."

Fixed monetary rule

[edit]Friedman proposed a fixed monetary rule, called Friedman's k-percent rule, where the money supply would be automatically increased by a fixed percentage per year. The rate should equal the growth rate of real GDP, leaving the price level unchanged. For instance, if the economy is expected to grow at 2 percent in a given year, the Fed should allow the money supply to increase by 2 percent. Because discretionary monetary policy would be as likely to destabilise as to stabilise the economy, Friedman advocated that the Fed be bound to fixed rules in conducting its policy.[10]

Opposition to the gold standard

[edit]Most monetarists oppose the gold standard. Friedman viewed a pure gold standard as impractical. For example, whereas one of the benefits of the gold standard is that the intrinsic limitations to the growth of the money supply by the use of gold would prevent inflation, if the growth of population or increase in trade outpaces the money supply, there would be no way to counteract deflation and reduced liquidity (and any attendant recession) except for the mining of more gold. But he also admitted that if a government was willing to surrender control over its monetary policy and not to interfere with economic activities, a gold-based economy would be possible.[11]

Rise

[edit]Clark Warburton is credited with making the first solid empirical case for the monetarist interpretation of business fluctuations in a series of papers from 1945.[1]p. 493 Within mainstream economics, the rise of monetarism started with Milton Friedman's 1956 restatement of the quantity theory of money. Friedman argued that the demand for money could be described as depending on a small number of economic variables.[12]

Thus, according to Friedman, when the money supply expanded, people would not simply wish to hold the extra money in idle money balances; i.e., if they were in equilibrium before the increase, they were already holding money balances to suit their requirements, and thus after the increase they would have money balances surplus to their requirements. These excess money balances would therefore be spent and hence aggregate demand would rise. Similarly, if the money supply were reduced people would want to replenish their holdings of money by reducing their spending. In this, Friedman challenged a simplification attributed to Keynes suggesting that "money does not matter."[12] Thus the word 'monetarist' was coined.

The popularity of monetarism picked up in political circles when the prevailing view of neo-Keynesian economics seemed unable to explain the contradictory problems of rising unemployment and inflation in response to the Nixon shock in 1971 and the oil shocks of 1973. On one hand, higher unemployment seemed to call for reflation, but on the other hand rising inflation seemed to call for disinflation. The social-democratic post-war consensus that had prevailed in first world countries was thus called into question by the rising neoliberal political forces.[2]

Monetarism in the US and the UK

[edit]In 1979, United States President Jimmy Carter appointed as Federal Reserve Chief Paul Volcker, who made fighting inflation his primary objective, and who restricted the money supply (in accordance with the Friedman rule) to tame inflation in the economy. The result was a major rise in interest rates, not only in the United States; but worldwide. The "Volcker shock" continued from 1979 to the summer of 1982, decreasing inflation and increasing unemployment.[13]

In May 1979, Margaret Thatcher, Leader of the Conservative Party in the United Kingdom, won the general election, defeating the sitting Labour Government led by James Callaghan. By that time, the UK had endured several years of severe inflation, which was rarely below the 10% mark and stood at 10.3% by the time of the election.[14] Thatcher implemented monetarism as the weapon in her battle against inflation, and succeeded at reducing it to 4.6% by 1983. However, unemployment in the United Kingdom increased from 5.7% in 1979 to 12.2% in 1983, reaching 13.0% in 1982; starting with the first quarter of 1980, the UK economy contracted in terms of real gross domestic product for six straight quarters.[15]

Decline

[edit]Monetarist ascendancy was brief, however.[10] The period when major central banks focused on targeting the growth of money supply, reflecting monetarist theory, lasted only for a few years, in the US from 1979 to 1982.[16]

The money supply is useful as a policy target only if the relationship between money and nominal GDP, and therefore inflation, is stable and predictable. This implies that the velocity of money must be predictable. In the 1970s velocity had seemed to increase at a fairly constant rate, but in the 1980s and 1990s velocity became highly unstable, experiencing unpredictable periods of increases and declines. Consequently, the stable correlation between the money supply and nominal GDP broke down, and the usefulness of the monetarist approach came into question. Many economists who had been convinced by monetarism in the 1970s abandoned the approach after this experience.[10]

The changing velocity originated in shifts in the demand for money and created serious problems for the central banks. This provoked a thorough rethinking of monetary policy. In the early 1990s central banks started focusing on targeting inflation directly using the short-run interest rate as their central policy variable, abandoning earlier emphasis on money growth. The new strategy proved successful, and today most major central banks follow a flexible inflation targeting.[5]: 483–485

Measurement Issues on the Stability of Money Demand

[edit]While monetarism's influence on policy diminished in the 1980s, subsequent research suggests that the apparent instability in money demand functions may have stemmed from measurement issues rather than a fundamental breakdown in the money-income relationship. Barnett and others argued that simple-sum monetary aggregates, which weight all monetary components equally regardless of their liquidity characteristics, introduce significant measurement error that obscures stable underlying relationships[17].

Studies using theoretically-grounded Divisia monetary aggregates, which weight monetary components based on their "monetary services" or liquidity properties, have found considerably more stable money demand relationships. For instance, Belongia and Ireland demonstrated that money demand equations using Divisia measures remain stable even through periods of financial innovation and policy regime changes that destabilized traditional simple-sum specifications[18].

This finding has important implications for monetary policy frameworks. The breakdown in simple-sum money demand relationships was a key factor in central banks abandoning monetary targeting in favor of interest rate rules. However, research using Divisia aggregates suggests that money could still serve as a useful policy indicator or intermediate target if properly measured[19].

The stability of Divisia money demand functions has been demonstrated across different time periods and countries. For example, Hendrickson found that replacing simple-sum with Divisia measures resolves apparent instabilities in U.S. money demand, while similar results have been documented for other economies[20].

These findings suggest that the historical shift away from monetary aggregates in policy frameworks may have been premature and based on flawed measurement rather than a true breakdown in the relationship between money and economic activity. While most central banks continue to focus primarily on interest rates, the stability of properly-measured money demand functions indicates that monetary aggregates could potentially play a more prominent role in policy frameworks[21].

Legacy

[edit]Even though monetarism failed in practical policy, and the close attention to money growth which was at the heart of monetarist analysis is rejected by most economists today, some aspects of monetarism have found their way into modern mainstream economic thinking.[10][22] Among them are the belief that controlling inflation should be a primary responsibility of the central bank.[10] It is also widely recognized that monetary policy, as well as fiscal policy, can affect output in the short run.[5]: 511 In this way, important monetarist thoughts have been subsumed into the new neoclassical synthesis or consensus view of macroeconomics that emerged in the 2000s.[23][5]: 518

Notable proponents

[edit]See also

[edit]- Chicago school of economics

- Demurrage (currency)

- Fiscalism (usually contrasted to monetarism)

- Market monetarism

- Modern Monetary Theory

- Money creation - process in which private banks (primarily) or Central banks (quantitative easing) create money

References

[edit]- ^ a b Phillip Cagan, 1987. "Monetarism", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, Reprinted in John Eatwell et al. (1989), Money: The New Palgrave, pp. 195–205, 492–97.

- ^ a b Harvey, David (2005). A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928326-2.

- ^ Friedman, Milton (2008). Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691003542. OCLC 994352014.

- ^ Doherty, Brian (June 1995). "Best of Both Worlds". Reason. Retrieved 28 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Blanchard, Olivier; Amighini, Alessia; Giavazzi, Francesco (2017). Macroeconomics: a European perspective (3rd ed.). Pearson. ISBN 978-1-292-08567-8.

- ^ Dimand, Robert W. (2016). "Monetary Economics, History of". The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2721-1. ISBN 978-1-349-95121-5.

- ^ Milton Friedman (1956), "The Quantity Theory of Money: A Restatement" in Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, edited by M. Friedman.]

- ^ Bordo, Michael D. (1989). "The Contribution of A Monetury History". Money, History, & International Finance: Essays in Honor of Anna J. Schwartz. The Increase in Reserve Requirements, 1936-37. University of Chicago Press. p. 46. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.736.9649. ISBN 0-226-06593-6. Retrieved 25 July 2019.

- ^ Milton Friedman; Anna Schwartz (2008). The Great Contraction, 1929–1933 (New ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13794-0.

- ^ a b c d e Jahan, Sarwat; Papageorgiou, Chris (28 February 2014). "Back to Basics What Is Monetarism?: Its emphasis on money's importance gained sway in the 1970s". Finance & Development. 51 (1). doi:10.5089/9781484312025.022.A012 (inactive 1 November 2024). Retrieved 16 October 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Monetary Central Planning and the State, Part 27: Milton Friedman's Second Thoughts on the Costs of Paper Money". Archived from the original on 14 November 2012.

- ^ a b Friedman, Milton (1970). "A Theoretical Framework for Monetary Analysis". Journal of Political Economy. 78 (2): 193–238 [p. 210]. doi:10.1086/259623. JSTOR 1830684. S2CID 154459930.

- ^ Reichart Alexandre & Abdelkader Slifi (2016). 'The Influence of Monetarism on Federal Reserve Policy during the 1980s.' Cahiers d'économie Politique/Papers in Political Economy, (1), pp. 107–50. https://www.cairn.info/revue-cahiers-d-economie-politique-2016-1-page-107.htm

- ^ Healey, Nigel M. (1990). "Fighting Inflation In Britain". Challenge. 33 (2): 37–41. doi:10.1080/05775132.1990.11471411. ISSN 0577-5132. JSTOR 40721141.

- ^ "Real Gross Domestic Product for United Kingdom, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis". January 1975. Retrieved 16 December 2018.

- ^ Mattos, Olivia Bullio (1 January 2022). "Chapter Seventeen - Monetary policy after the subprime crisis: a Post-Keynesian critique". Handbook of Economic Stagnation. Academic Press. pp. 341–359. ISBN 978-0-12-815898-2. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Barnett, William A. (1980). "Economic monetary aggregates an application of index number and aggregation theory". Journal of Econometrics. 14 (1): 11–48. doi:10.1016/0304-4076(80)90070-6.

- ^ Belongia, Michael T.; Ireland, Peter N. (2019). "The Demand for Divisia Money: Theory and Evidence". Journal of Macroeconomics. 61: 103128. doi:10.1016/j.jmacro.2019.103128.

- ^ Serletis, Apostolos; Gogas, Periklis (2014). "Divisia Monetary Aggregates, the Great Ratios, and Classical Money Demand Functions". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 46 (1): 229–241. doi:10.1111/jmcb.12103.

- ^ Hendrickson, Joshua R. (2014). "Redundancy or Mismeasurement? A Reappraisal of Money". Macroeconomic Dynamics. 18 (7): 1437–1465. doi:10.1017/S1365100513000023.

- ^ Barnett, William A.; Liu, Jia; Mattson, Ryan S.; van den Noort, Jeff (2013). "The new CFS Divisia monetary aggregates: Design, construction, and data sources". Open Economies Review. 24 (1): 101–124. doi:10.1007/s11079-012-9251-7.

- ^ Long, De; Bradford, J. (March 2000). "The Triumph of Monetarism?". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 14 (1): 83–94. doi:10.1257/jep.14.1.83. ISSN 0895-3309. Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ^ Goodfriend, Marvin; King, Robert G. (January 1997). "The New Neoclassical Synthesis and the Role of Monetary Policy". NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1997, Volume 12. MIT Press. pp. 231–296.

Further reading

[edit]- Andersen, Leonall C., and Jerry L. Jordan, 1968. "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilisation", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review (November), pp. 11–24. PDF (30 sec. load: press +) and HTML.

- _____, 1969. "Monetary and Fiscal Actions: A Test of Their Relative Importance in Economic Stabilisation — Reply", Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review (April), pp. 12–16. PDF (15 sec. load; press +) and HTML.

- Brunner, Karl, and Allan H. Meltzer, 1993. Money and the Economy: Issues in Monetary Analysis, Cambridge. Description and chapter previews, pp. ix–x.

- Cagan, Phillip, 1965. Determinants and Effects of Changes in the Stock of Money, 1875–1960. NBER. Foreword by Milton Friedman, pp. xiii–xxviii. Table of Contents.

- Friedman, Milton, ed. 1956. Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money, Chicago. Chapter 1 is previewed at Friedman, 2005, ch. 2 link.

- _____, 1960. A Program for Monetary Stability. Fordham University Press.

- _____, 1968. "The Role of Monetary Policy", American Economic Review, 58(1), pp. 1–17 (press +).

- _____, [1969] 2005. The Optimum Quantity of Money. Description and table of contents, with previews of 3 chapters.

- Friedman, Milton, and David Meiselman, 1963. "The Relative Stability of Monetary Velocity and the Investment Multiplier in the United States, 1897–1958", in Stabilization Policies, pp. 165–268. Prentice-Hall/Commission on Money and Credit, 1963.

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, 1963a. "Money and Business Cycles", Review of Economics and Statistics, 45(1), Part 2, Supplement, p. p. 32–64. Reprinted in Schwartz, 1987, Money in Historical Perspective, ch. 2.

- _____. 1963b. A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960. Princeton. Page-searchable links to chapters on 1929-41 and 1948–60

- Johnson, Harry G., 1971. "The Keynesian Revolutions and the Monetarist Counter-Revolution", American Economic Review, 61(2), p. p. 1–14. Reprinted in John Cunningham Wood and Ronald N. Woods, ed., 1990, Milton Friedman: Critical Assessments, v. 2, p. p. 72 – 88. Routledge,

- Laidler, David E.W., 1993. The Demand for Money: Theories, Evidence, and Problems, 4th ed. Description.

- Schwartz, Anna J., 1987. Money in Historical Perspective, University of Chicago Press. Description and Chapter-preview links, pp. vii-viii.

- Warburton, Clark, 1966. Depression, Inflation, and Monetary Policy; Selected Papers, 1945–1953 Johns Hopkins Press. Amazon Summary in Anna J. Schwartz, Money in Historical Perspective, 1987.

External links

[edit]- "Monetarism" at The New School's Economics Department's History of Economic Thought website.

- McCallum, Bennett T. (2008). "Monetarism". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

- Monetarism from the Economics A–Z of The Economist