Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

| Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics[b] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signed | 23 August 1939 |

| Location | Moscow, Soviet Union |

| Expiration | 23 August 1949 (planned)22 June 1941 (terminated)30 July 1941 (officially declared null and void) |

| Signatories | |

| Parties | |

| Languages |

|

| Full text | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Pre-leadership Leader of the Soviet Union Political ideology Works

Legacy  |

||

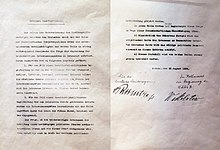

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, officially the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,[1][2] and also known as the Hitler–Stalin Pact[3][4] and the Nazi–Soviet Pact,[5] was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, with a secret protocol establishing Soviet and German spheres of influence across Eastern Europe.[6] The pact was signed in Moscow on 24 August 1939 (backdated 23 August 1939) by Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov and German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop.[7]

The treaty was the culmination of negotiations around the 1938–1939 deal discussions, after tripartite discussions with the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and France had broken down, and committed neither government would aid or ally itself with an enemy of the other, for the next 10 years. Under the Secret Protocol, Poland was to be shared, while Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Bessarabia went to the Soviet Union. The protocol also recognized the interest of Lithuania in the Vilnius region. In the west, rumoured existence of the Secret Protocol was proven only when it was made public during the Nuremberg trials.[8]

A week after signing the pact, on 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. On 17 September, one day after a Soviet–Japanese ceasefire came into effect after the Battles of Khalkhin Gol,[9] and one day after the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union approved the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact,[10] Stalin, stating concern for ethnic Ukrainians and Belarusians in Poland, ordered the Soviet invasion of Poland. After a short war ending in military defeat for Poland, Germany and the Soviet Union drew up a new border between them on formerly Polish territory in the supplementary protocol of the German–Soviet Frontier Treaty.

In March 1940, parts of the Karelia and Salla regions in Finland were annexed by the Soviet Union following the Winter War. The Soviet annexation of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and parts of Romania (Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region) followed. Stalin's invasion of Bukovina in 1940 violated the pact, since it went beyond the Soviet sphere of influence that had been agreed with the Axis.[11]

The territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union following the 1939 Soviet invasion east of the Curzon line remained in the Soviet Union after the war and are now in Ukraine and Belarus. Vilnius was given to Lithuania. Only Podlaskie and a small part of Galicia east of the San River, around Przemyśl, were returned to Poland. Of all the other territories annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939–1940, those detached from Finland (Western Karelia, Petsamo), Estonia (Estonian Ingria and Petseri County) and Latvia (Abrene) remain part of Russia, the successor state to the Russian SFSR and the Soviet Union after the collapse of the USSR in 1991. The territories annexed from Romania were also integrated into the Soviet Union (such as the Moldavian SSR, or oblasts of the Ukrainian SSR). The core of Bessarabia now forms Moldova. Northern Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region now form the Chernivtsi Oblast of Ukraine. Southern Bessarabia is part of the Odessa Oblast, which is also now in Ukraine.

The pact was terminated on 22 June 1941, when Germany launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union, in pursuit of the ideological goal of Lebensraum.[12] The Anglo-Soviet Agreement succeeded it. After the war, Ribbentrop was convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg trials and executed in 1946, whilst Molotov died in 1986.

Background

[edit]| Events leading to World War II |

|---|

The outcome of World War I was disastrous for both the German and the Russian empires. The Russian Civil War broke out in late 1917 after the Bolshevik Revolution and Vladimir Lenin, the first leader of the new Soviet Russia, recognised the independence of Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland. Moreover, facing a German military advance, Lenin and Trotsky were forced to agree to the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk,[13] which ceded many western Russian territories to Germany. After the German collapse, a multinational Allied-led army intervened in the civil war (1917–1922).[14]

On 16 April 1922, the German Weimar Republic and the Soviet Union agreed to the Treaty of Rapallo in which they renounced territorial and financial claims against each other.[15] Each party also pledged neutrality in the event of an attack against the other with the Treaty of Berlin (1926).[16] Trade between the two countries had fallen sharply after World War I, but trade agreements signed in the mid-1920s helped to increase trade to 433 million ℛ︁ℳ︁ per year by 1927.[17]

At the beginning of the 1930s, the Nazi Party's rise to power increased tensions between Germany and the Soviet Union, along with other countries with ethnic Slavs, who were considered "Untermenschen" (subhuman) according to Nazi racial ideology.[18] Moreover, the antisemitic Nazis associated ethnic Jews with both communism and financial capitalism, both of which they opposed.[19][20] Nazi theory held that Slavs in the Soviet Union were being ruled by "Jewish Bolshevik" masters.[21] Hitler had spoken of an inevitable battle for the acquisition of land for Germany in the east.[22] The resulting manifestation of German anti-Bolshevism and an increase in Soviet foreign debts caused a dramatic decline in German–Soviet trade.[c] Imports of Soviet goods to Germany fell to 223 million ℛ︁ℳ︁ in 1934 by the more isolationist Stalinist regime asserting power and by the abandonment of postwar Treaty of Versailles military controls, both of which decreased Germany's reliance on Soviet imports.[17][24][clarification needed]

In 1935 Germany, after a previous German–Polish declaration of non-aggression, Hermann Goring proposed a military alliance with Poland against the Soviet Union, but this was rejected.[25]

In 1936, Germany and Fascist Italy supported the Spanish Nationalists in the Spanish Civil War, but the Soviets supported the Spanish Republic.[26] Thus, the Spanish Civil War became a proxy war between Germany and the Soviet Union.[27] In 1936, Germany and Japan entered the Anti-Comintern Pact.[28] and they were joined a year later by Italy,[29] despite Italy having previously signed the Italo-Soviet Pact.[30]

On 31 March 1939, Britain extended a guarantee to Poland that "if any action clearly threatened Polish independence, and if the Poles felt it vital to resist such action by force, Britain would come to their aid". Hitler was furious since that meant that the British were committed to political interests in Europe and that his land grabs such as the takeover of Czechoslovakia would no longer be taken lightly. His response to the political checkmate would later be heard at a rally in Wilhelmshaven: "No power on earth would be able to break German might, and if the Western Allies thought Germany would stand by while they marshalled their 'satellite states' to act in their interests, then they were sorely mistaken". Ultimately, Hitler's discontent with a British-Polish alliance led to a restructuring of strategy towards Moscow. Alfred Rosenberg wrote that he had spoken to Hermann Göring of the potential pact with the Soviet Union: "When Germany's life is at stake, even a temporary alliance with Moscow must be contemplated". Sometime in early May 1939 at Berghof, Ribbentrop showed Hitler a film of Stalin viewing his military in a recent parade. Hitler became intrigued with the idea of allying with the Soviets and Ribbentrop recalled Hitler saying that Stalin "looked like a man he could do business with". Ribbentrop was then given the nod to pursue negotiations with Moscow.[31]

Munich Conference

[edit]Hitler's fierce anti-Soviet rhetoric was one of the reasons that Britain and France decided that Soviet participation in the 1938 Munich Conference on Czechoslovakia would be both dangerous and useless.[32] In the Munich Agreement that followed[33] the conference agreed to a German annexation of part of Czechoslovakia in late 1938, but in early 1939 it had been completely dissolved.[34] The policy of appeasement toward Germany was conducted by the governments of British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier.[35] The policy immediately raised the question of whether the Soviet Union could avoid being next on Hitler's list.[36] The Soviet leadership believed that the West wanted to encourage German aggression in the East[37] and to stay neutral in a war initiated by Germany in the hope that Germany and the Soviet Union would wear each other out and put an end to both regimes.[38]

For Germany, an autarkic economic approach and an alliance with Britain were impossible and so closer relations with the Soviet Union to obtain raw materials became necessary.[39] Besides economic reasons, an expected British blockade during a war would also create massive shortages for Germany in a number of key raw materials.[40] After the Munich Agreement, the resulting increase in German military supply needs and Soviet demands for military machinery made talks between the two countries occur from late 1938 to March 1939.[41] Also, the third Soviet five-year plan required new infusions of technology and industrial equipment.[39][42][clarification needed] German war planners had estimated serious shortfalls of raw materials if Germany entered a war without the Soviet supply.[43]

On 31 March 1939, in response to Germany's defiance of the Munich Agreement and the creation of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia,[44] Britain pledged its support and that of France to guarantee the independence of Poland, Belgium, Romania, Greece and Turkey.[45] On 6 April, Poland and Britain agreed to formalise the guarantee as a military alliance, pending negotiations.[46] On 28 April, Hitler denounced the 1934 German–Polish declaration of non-aggression and the 1935 Anglo–German Naval Agreement.[47]

In mid-March 1939, attempting to contain Hitler's expansionism, the Soviet Union, Britain and France started to trade a flurry of suggestions and counterplans on a potential political and military agreement.[48][49] Informal consultations started in April, but the main negotiations began only in May.[49] Meanwhile, throughout early 1939, Germany had secretly hinted to Soviet diplomats that it could offer better terms for a political agreement than could Britain and France.[50][51][52]

The Soviet Union, which feared Western powers and the possibility of "capitalist encirclements", had little hope of preventing war and wanted nothing less than an ironclad military alliance with France and Britain[53] to provide guaranteed support for a two-pronged attack on Germany.[54] Stalin's adherence to the collective security line was thus purely conditional.[55] Britain and France believed that war could still be avoided and that since the Soviet Union was so weakened by the Great Purge[56] that it could not be a main military participant.[54] Many military sources[clarification needed] were at variance with the last point, especially after the Soviet victories over the Japanese Kwantung Army in the Manchuria.[57] France was more anxious to find an agreement with the Soviet Union than Britain was. As a continental power, France was more willing to make concessions and more fearful of the dangers of an agreement between the Soviet Union and Germany.[58] The contrasting attitudes partly explain why the Soviets have often been charged with playing a double game in 1939 of carrying on open negotiations for an alliance with Britain and France but secretly considering propositions from Germany.[58]

By the end of May, drafts had been formally presented.[49] In mid-June, the main tripartite negotiations started.[59] Discussions were focused on potential guarantees to Central and Eastern Europe in the case of German aggression.[60] The Soviets proposed to consider that a political turn towards Germany by the Baltic states would constitute an "indirect aggression" towards the Soviet Union.[61] Britain opposed such proposals because they feared the Soviets' proposed language would justify a Soviet intervention in Finland and the Baltic states or push those countries to seek closer relations with Germany.[62][63] The discussion of a definition of "indirect aggression" became one of the sticking points between the parties, and by mid-July, the tripartite political negotiations effectively stalled while the parties agreed to start negotiations on a military agreement, which the Soviets insisted had to be reached at the same time as any political agreement.[64] One day before the military negotiations began, the Soviet Politburo pessimistically expected the coming negotiations to go nowhere and formally decided to consider German proposals seriously.[65] The military negotiations began on 12 August in Moscow, with a British delegation headed by Admiral Sir Reginald Drax, French delegation headed by General Aimé Doumenc and the Soviet delegation headed by Kliment Voroshilov, the commissar of defence, and Boris Shaposhnikov, chief of the general staff. Without written credentials, Drax was not authorised to guarantee anything to the Soviet Union and had been instructed by the British government to prolong the discussions as long as possible and to avoid answering the question of whether Poland would agree to permit Soviet troops to enter the country if the Germans invaded.[66]

Negotiations

[edit]

Beginning of secret talks

[edit]From April to July, Soviet and German officials made statements on the potential for the beginning of political negotiations, but no actual negotiations took place.[67] "The Soviet Union had wanted good relations with Germany for years and was happy to see that feeling finally reciprocated", wrote the historian Gerhard L. Weinberg.[68] The ensuing discussion of a potential political deal between Germany and the Soviet Union had to be channeled into the framework of economic negotiations between the two countries, since close military and diplomatic connections that existed before the mid-1930s had been largely severed.[69] In May, Stalin replaced his foreign minister from 1930 to 1939, Maxim Litvinov, who had advocated rapprochement with the West and was also Jewish,[70] with Vyacheslav Molotov to allow the Soviet Union more latitude in discussions with more parties, instead of only Britain and France.[71]

On 23 August 1939, two Focke-Wulf Condors, containing German diplomats, officials, and photographers (about 20 in each plane), headed by Ribbentrop, descended into Moscow. As the Nazi emissaries stepped off the plane, a Soviet military band played "Deutschland, Deutschland über Alles". The Nazi arrival was well planned, with all aesthetics in order. The classic hammer and sickle was propped up next to the swastika of the Nazi flag that had been used in a local film studio for Soviet propaganda films. After stepping off the plane and shaking hands, Ribbentrop and Gustav Hilger along with German ambassador Friedrich-Werner von der Schulenburg and Stalin's chief bodyguard, Nikolai Vlasik, entered a limousine operated by the NKVD to travel to Red Square. The limousine arrived close to Stalin's office and was greeted by Alexander Poskrebyshev, the chief of Stalin's personal chancellery. The Germans were led up a flight of stairs to a room with lavish furnishings. Stalin and Molotov greeted the visitors, much to the Nazis' surprise. It was well known that Stalin avoided meeting foreign visitors, and so his presence at the meeting showed how seriously that the Soviets were taking the negotiations.[72]

In late July and early August 1939, Soviet and German officials agreed on most of the details of a planned economic agreement[73] and specifically addressed a potential political agreement,[74][75][76][d] which the Soviets stated could come only after an economic agreement.[78]

The German presence in the Soviet capital during negotiations can be regarded as rather tense. German pilot Hans Baur recalled that Soviet secret police followed every move. Their job was to inform authorities when he left his residence and where he was headed. Baur's guide informed him: "Another car would tack itself onto us and follow us fifty or so yards in the rear, and wherever we went and whatever we did, the secret police would be on our heels." Baur also recalled trying to tip his Russian driver, which led to a harsh exchange of words: "He was furious. He wanted to know whether this was the thanks he got for having done his best for us to get him into prison. We knew perfectly well it was forbidden to take tips."[72]

August negotiations

[edit]In early August, Germany and the Soviet Union worked out the last details of their economic deal[79] and started to discuss a political agreement. Both countries' diplomats explained to each other the reasons for the hostility in their foreign policy in the 1930s and found common ground in both countries' anticapitalism with Karl Schnurre stating: "there is one common element in the ideology of Germany, Italy, and the Soviet Union: opposition to the capitalist democracies" or that "it seems to us rather unnatural that a socialist state would stand on the side of the western democracies".[80][81][82][83]

At the same time, British, French, and Soviet negotiators scheduled three-party talks on military matters to occur in Moscow in August 1939 that aimed to define what the agreement would specify on the reaction of the three powers to a German attack.[62] The tripartite military talks, started in mid-August, hit a sticking point on the passage of Soviet troops through Poland if Germans attacked, and the parties waited as British and French officials overseas pressured Polish officials to agree to such terms.[84][85] Polish officials refused to allow Soviet troops into Polish territory if Germany attacked; Polish Foreign Minister Józef Beck pointed out that the Polish government feared that if the Red Army entered Polish territory, it would never leave.[86][87]

On 19 August, the 1939 German–Soviet Commercial Agreement was finally signed.[88] On 21 August, the Soviets suspended the tripartite military talks and cited other reasons.[50][89] The same day, Stalin received assurances that Germany would approve secret protocols to the proposed non-aggression pact that would place the half of Poland east of the Vistula River as well as Latvia, Estonia, Finland and Bessarabia in the Soviet sphere of influence.[90] That night, Stalin replied that the Soviets were willing to sign the pact and that he would receive Ribbentrop on 23 August.[91]

News leaks

[edit]

On 25 August 1939, the New York Times ran a front-page story by Otto D. Tolischus, "Nazi Talks Secret", whose subtitle included "Soviet and Reich Agree on East".[92] On 26 August 1939, the New York Times reported Japanese anger[93] and French communist surprise[94] over the pact. The same day, however, Tolischus filed a story that noted Nazi troops on the move near Gleiwitz (now Gliwice), which led to the false flag Gleiwitz incident on 31 August 1939.[95] On 28 August 1939, the New York Times was still reporting on fears of a Gleiwitz raid.[96] On 29 August 1939, the New York Times reported that the Supreme Soviet had failed on its first day of convening to act on the pact.[97] The same day, the New York Times also reported from Montreal, Canada, that American Professor Samuel N. Harper of the University of Chicago had stated publicly his belief that "the Russo-German non-aggression pact conceals an agreement whereby Russia and Germany may have planned spheres of influence for Eastern Europe".[4] On 30 August 1939, the New York Times reported a Soviet buildup on its Western frontiers by moving 200,000 troops from the Far East.[98]

Secret protocol

[edit]On 22 August, one day after talks broke down with France and Britain, Moscow revealed that Ribbentrop would visit Stalin the next day. The Soviets were still negotiating with the British and the French missions in Moscow. With the Western nations unwilling to accede to Soviet demands, Stalin instead entered a secret German–Soviet pact.[99] On 23 August, a ten-year non-aggression pact was signed with provisions that included consultation, arbitration if either party disagreed, neutrality if either went to war against a third power and no membership of a group "which is directly or indirectly aimed at the other". The article "On Soviet–German Relations" in the Soviet newspaper Izvestia of 21 August 1939, stated:

Following completion of the Soviet–German trade and credit agreement, there has arisen the question of improving political links between Germany and the USSR.[100]

There was also a secret protocol to the pact, which was revealed only after Germany's defeat in 1945[101] although hints about its provisions had been leaked much earlier, so as to influence Lithuania.[102] According to the protocol, Poland, Romania, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, and Finland were divided into German and Soviet "spheres of influence".[101] In the north, Finland, Estonia, and Latvia were assigned to the Soviet sphere.[101] Poland was to be partitioned in the event of its "political rearrangement": the areas east of the Pisa, Narew, Vistula, and San rivers would go to the Soviet Union, and Germany would occupy the west.[101] Lithuania, which was adjacent to East Prussia, was assigned to the German sphere of influence, but a second secret protocol, agreed to in September 1939, reassigned Lithuania to the Soviet Union.[103] According to the protocol, Lithuania would be granted its historical capital, Vilnius, which was part of Poland during the interwar period. Another clause stipulated that Germany would not interfere with the Soviet Union's actions towards Bessarabia, which was then part of Romania.[101] As a result, Bessarabia as well as the Northern Bukovina and Hertsa regions were occupied by the Soviets and integrated into the Soviet Union.

At the signing, Ribbentrop and Stalin enjoyed warm conversations, exchanged toasts and further addressed the prior hostilities between the countries in the 1930s.[104] They characterised Britain as always attempting to disrupt Soviet–German relations and stated that the Anti-Comintern Pact was aimed not at the Soviet Union but actually at Western democracies and "frightened principally the City of London [British financiers] and the English shopkeepers."[105]

Revelation

[edit]The agreement stunned the world. John Gunther, in Moscow in August 1939, recalled how the news of the 19 August commercial agreement surprised journalists and diplomats, who hoped for world peace. They did not expect the 21 August announcement of the non-aggression pact: "Nothing more unbelievable could be imagined. Astonishment and skepticism turned quickly to consternation and alarm".[106] The news was met with utter shock and surprise by government leaders and media worldwide, most of whom were aware of only the British–French–Soviet negotiations, which had taken place for months;[50][106] by Germany's allies, notably Japan; by the Comintern and foreign Communist parties; and Jewish communities all around the world.[107]

On 24 August, Pravda and Izvestia carried news of the pact's public portions, complete with the now-famous front-page picture of Molotov signing the treaty with a smiling Stalin looking on.[50] The same day, German diplomat Hans von Herwarth, whose grandmother was Jewish, informed Italian diplomat Guido Relli[108] and American chargé d'affaires Charles Bohlen of the secret protocol on the vital interests in the countries' allotted "spheres of influence" but failed to reveal the annexation rights for "territorial and political rearrangement".[109][110] The agreement's public terms so exceeded the terms of an ordinary non-aggression treaty—requiring that both parties consult with each other, and not aid a third party attacking either—that Gunther heard a joke that Stalin had joined the anti-Comintern pact.[106] Time Magazine repeatedly referred to the Pact as the "Communazi Pact" and its participants as "communazis" until April 1941.[111][112][113][114][115]

Soviet propaganda and representatives went to great lengths to minimize the importance of the fact that they had opposed and fought the Germans in various ways for a decade prior to signing the pact. Molotov tried to reassure the Germans of his good intentions by commenting to journalists that "fascism is a matter of taste".[116] For its part, Germany also did a public volte-face regarding its virulent opposition to the Soviet Union, but Hitler still viewed an attack on the Soviet Union as "inevitable".[117]

Concerns over the possible existence of a secret protocol were expressed first by the intelligence organizations of the Baltic states[citation needed] only days after the pact was signed. Speculation grew stronger when Soviet negotiators referred to its content during the negotiations for military bases in those countries (see occupation of the Baltic States).

The day after the pact was signed, the Franco-British military delegation urgently requested a meeting with Soviet military negotiator Kliment Voroshilov.[118] On 25 August, Voroshilov told them that "in view of the changed political situation, no useful purpose can be served in continuing the conversation".[118] The same day, Hitler told the British ambassador to Berlin that the pact with the Soviets prevented Germany from facing a two-front war, which changed the strategic situation from that in World War I, and that Britain should accept his demands on Poland.[119]

On 25 August, Hitler was surprised when Britain joined a defense pact with Poland.[119] Hitler postponed his plans for an invasion of Poland on 26 August to 1 September.[119][120] In accordance with the defence pact, Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September.[121]

Consequences in Finland, Poland, the Baltic States and Romania

[edit]

Initial invasions

[edit]On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland from the west.[122] Within a few days, Germany began conducting massacres of Polish and Jewish civilians and POWs,[123][124] which took place in over 30 towns and villages in the first month of the German occupation.[125][126][127] The Luftwaffe also took part by strafing fleeing civilian refugees on roads and by carrying out a bombing campaign.[128][129][130] The Soviet Union assisted German air forces by allowing them to use signals broadcast by the Soviet radio station at Minsk, allegedly "for urgent aeronautical experiments".[131] Hitler declared at Danzig:

Poland never will rise again in the form of the Versailles treaty. That is guaranteed not only by Germany, but also ... Russia.[132]

In the opinion of Robert Service, Stalin did not move instantly but was waiting to see whether the Germans would halt within the agreed area, and the Soviet Union also needed to secure the frontier in the Soviet–Japanese Border Wars.[134] On 17 September, the Red Army invaded Poland, violating the 1932 Soviet–Polish Non-Aggression Pact, and occupied the Polish territory assigned to it by the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. That was followed by co-ordination with German forces in Poland.[135] Polish troops already fighting much stronger German forces on its west desperately tried to delay the capture of Warsaw. Consequently, Polish forces could not mount significant resistance against the Soviets.[136] On 18 September, The New York Times published an editorial arguing that "Hitlerism is brown communism, Stalinism is red fascism...The world will now understand that the only real 'ideological' issue is one between democracy, liberty and peace on the one hand and despotism, terror and war on the other."[137]

On 21 September, Marshal of the Soviet Union Voroshilov, German military attaché General Köstring, and other officers signed a formal agreement in Moscow co-ordinating military movements in Poland, including the "purging" of saboteurs and the Red Army assisting with destruction of the "enemy".[138] Joint German–Soviet parades were held in Lviv and Brest-Litovsk, and the countries' military commanders met in the latter city.[139] Stalin had decided in August that he was going to liquidate the Polish state, and a German–Soviet meeting in September addressed the future structure of the "Polish region".[139] Soviet authorities immediately started a campaign of Sovietisation[140][141] of the newly acquired areas. The Soviets organised staged elections,[142] the result of which was to become a legitimisation of the Soviet annexation of eastern Poland.[143]

Modification of secret protocols

[edit]

Eleven days after the Soviet invasion of the Polish Kresy, the secret protocol of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was modified by the German–Soviet Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Demarcation,[144] allotting Germany a larger part of Poland and transferring Lithuania, with the exception of the left bank of the River Scheschupe, the "Lithuanian Strip", from the envisioned German sphere to the Soviet sphere.[145] On 28 September 1939, the Soviet Union and German Reich issued a joint declaration in which they declared:

After the Government of the German Reich and the Government of the USSR have, by means of the treaty signed today, definitively settled the problems arising from the collapse of the Polish state and have thereby created a sure foundation for lasting peace in the region, they mutually express their conviction that it would serve the true interest of all peoples to put an end to the state of war existing at present between Germany on the one side and England and France on the other. Both Governments will, therefore, direct their common efforts, jointly with other friendly powers if the occasion arises, toward attaining this goal as soon as possible. Should, however, the efforts of the two Governments remain fruitless, this would demonstrate the fact that England and France are responsible for the continuation of the war, whereupon, in case of the continuation of the war, the Governments of Germany and of the USSR shall engage in mutual consultations with regard to necessary measures.[146]

On 3 October, Friedrich Werner von der Schulenburg, the German ambassador in Moscow, informed Joachim Ribbentrop that the Soviet government was willing to cede the city of Vilnius and its environs. On 8 October 1939, a new Nazi-Soviet agreement was reached by an exchange of letters between Vyacheslav Molotov and the German ambassador.[147]

The Baltic states of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania were given no choice but to sign a so-called "Pact of Defence and Mutual Assistance", which permitted the Soviet Union to station troops in them.[145]

Soviet war with Finland and Katyn massacre

[edit]

After the Baltic states had been forced to accept treaties,[148] Stalin turned his sights on Finland and was confident that its capitulation could be attained without great effort.[149] The Soviets demanded territories on the Karelian Isthmus, the islands of the Gulf of Finland and a military base near the Finnish capital, Helsinki,[150][151] which Finland rejected.[152] The Soviets staged the shelling of Mainila on 26 November and used it as a pretext to withdraw from the Soviet–Finnish Non-Aggression Pact.[153] On 30 November, the Red Army invaded Finland, launching the Winter War with the aim of annexing Finland into the Soviet Union.[154][155][156] The Soviets formed the Finnish Democratic Republic to govern Finland after Soviet conquest.[157][158][159][160] The leader of the Leningrad Military District, Andrei Zhdanov, commissioned a celebratory piece from Dmitri Shostakovich, Suite on Finnish Themes, to be performed as the marching bands of the Red Army would be parading through Helsinki.[161] After Finnish defenses surprisingly held out for over three months and inflicted stiff losses on Soviet forces, under the command of Semyon Timoshenko, the Soviets settled for an interim peace. Finland ceded parts of Karelia and Salla (9% of Finnish territory),[162][page needed] which resulted in approximately 422,000 Karelians (12% of Finland's population) losing their homes.[163] Soviet official casualty counts in the war exceeded 200,000[164] although Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev later claimed that the casualties may have been one million.[165]

Around that time, after several Gestapo–NKVD conferences, Soviet NKVD officers also conducted lengthy interrogations of 300,000 Polish POWs in camps[166][167][168][169] that were a selection process to determine who would be killed.[170] On 5 March 1940, in what would later be known as the Katyn massacre,[170][171][172] 22,000 members of the military as well as intellectuals were executed, labelled "nationalists and counterrevolutionaries" or kept at camps and prisons in western Ukraine and Belarus.[citation needed]

Soviet Union occupies the Baltic states and part of Romania

[edit]

In mid-June 1940, while international attention focused on the German invasion of France, Soviet NKVD troops raided border posts in Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia.[145][173] State administrations were liquidated and replaced by Soviet cadres,[145] who deported or killed 34,250 Latvians, 75,000 Lithuanians and almost 60,000 Estonians.[174] Elections took place, with a single pro-Soviet candidate listed for many positions, and the resulting people's assemblies immediately requesting admission into the Soviet Union, which was granted.[145] (The Soviets annexed the whole of Lithuania, including the Šešupė area, which had been earmarked for Germany.)

Finally, on 26 June, four days after the armistice between France and Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum that demanded Bessarabia and unexpectedly Northern Bukovina from Romania.[175] Two days later, the Romanians acceded to the Soviet demands, and the Soviets occupied the territories. The Hertsa region was initially not requested by the Soviets but was later occupied by force after the Romanians had agreed to the initial Soviet demands.[175] The subsequent waves of deportations began in Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina.

Beginnings of Operation Tannenberg and other Nazi atrocities

[edit]At the end of October 1939, Germany enacted the death penalty for disobedience to the German occupation.[176] Germany began a campaign of "Germanization", which meant assimilating the occupied territories politically, culturally, socially and economically into the German Reich.[177][178][179] 50,000–200,000 Polish children were kidnapped to be Germanised.[180][181]

The elimination of Polish elites and intelligentsia was part of Generalplan Ost. The Intelligenzaktion, a plan to eliminate the Polish intelligentsia, Poland's 'leadership class', took place soon after the German invasion of Poland and lasted from fall of 1939 to the spring of 1940. As the result of the operation, in ten regional actions, about 60,000 Polish nobles, teachers, social workers, priests, judges and political activists were killed.[182][183] It was continued in May 1940, when Germany launched AB-Aktion,[180] More than 16,000 members of the intelligentsia were murdered in Operation Tannenberg alone.[184]

Germany also planned to incorporate all of the land into Nazi Germany.[178] That effort resulted in the forced resettlement of two million Poles. Families were forced to travel in the severe winter of 1939–1940, leaving behind almost all of their possessions without compensation.[178] As part of Operation Tannenberg alone, 750,000 Polish peasants were forced to leave, and their property was given to Germans.[185] A further 330,000 were murdered.[186] Germany planned the eventual move of ethnic Poles to Siberia.[187][188]

Although Germany used forced labourers in most other occupied countries, Poles and other Slavs were viewed as inferior by Nazi propaganda and thus better suited for such duties.[180] Between 1 and 2.5 million Polish citizens[180][189] were transported to the Reich for forced labour.[190][191] All Polish males were made to perform forced labour.[180] While ethnic Poles were subject to selective persecution, all ethnic Jews were targeted by the Reich.[189] In the winter of 1939–40, about 100,000 Jews were thus deported to Poland.[192] They were initially gathered into massive urban ghettos,[193] such as the 380,000 held in the Warsaw Ghetto, where large numbers died of starvation and diseases under their harsh conditions, including 43,000 in the Warsaw Ghetto alone.[189][194][195] Poles and ethnic Jews were imprisoned in nearly every camp of the extensive concentration camp system in German-occupied Poland and the Reich. In Auschwitz, which began operating on 14 June 1940, 1.1 million people perished.[196][197]

Romania and Soviet republics

[edit]

In the summer of 1940, fear of the Soviet Union, in conjunction with German support for the territorial demands of Romania's neighbours and the Romanian government's own miscalculations, resulted in more territorial losses for Romania. Between 28 June and 4 July, the Soviet Union occupied and annexed Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina and the Hertsa region of Romania.[198]

On 30 August, Ribbentrop and Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano issued the Second Vienna Award, giving Northern Transylvania to Hungary. On 7 September, Romania ceded Southern Dobruja to Bulgaria (Axis-sponsored Treaty of Craiova).[199] After various events over the following months, Romania increasingly took on the aspect of a German-occupied country.[199]

The Soviet-occupied territories were converted into republics of the Soviet Union. During the two years after the annexation, the Soviets arrested approximately 100,000 Polish citizens[200] and deported between 350,000 and 1,500,000, of whom between 250,000 and 1,000,000 died, mostly civilians.[201][e] Forced re-settlements into gulag labour camps and exile settlements in remote areas of the Soviet Union occurred.[141] According to Norman Davies,[207] almost half of them were dead by July 1940.[208]

Further secret protocol modifications settling borders and immigration issues

[edit]On 10 January 1941, Germany and the Soviet Union signed an agreement settling several ongoing issues.[209] Secret protocols in the new agreement modified the "Secret Additional Protocols" of the German–Soviet Boundary and Friendship Treaty, ceding the Lithuanian Strip to the Soviet Union in exchange for US$7.5 million (31.5 million ℛ︁ℳ︁).[209] The agreement formally set the border between Germany and the Soviet Union between the Igorka River and the Baltic Sea.[210] It also extended trade regulation of the 1940 German-Soviet Commercial Agreement until 1 August 1942, increased deliveries above the levels of the first year of that agreement,[210] settled trading rights in the Baltics and Bessarabia, calculated the compensation for German property interests in the Baltic states that were now occupied by the Soviets and covered other issues.[209] It also covered the migration to Germany within 2+1⁄2 months of ethnic Germans and German citizens in Soviet-held Baltic territories and the migration to the Soviet Union of Baltic and "White Russian" "nationals" in the German-held territories.[210]

Soviet–German relations

[edit]

Early political issues

[edit]Before the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was announced, Western communists denied that such a treaty would be signed. Herbert Biberman, a future member of the Hollywood Ten, denounced rumours as "Fascist propaganda". Earl Browder, the head of the Communist Party USA, stated that "there is as much chance of agreement as of Earl Browder being elected president of the Chamber of Commerce."[211] Gunther wrote, however, that some knew "communism and Fascism were more closely allied than was normally understood", and Ernst von Weizsäcker had told Nevile Henderson on 16 August that the Soviet Union would "join in sharing in the Polish spoils".[106] In September 1939, the Comintern suspended all anti-Nazi and anti-fascist propaganda and explained that the war in Europe was a matter of capitalist states attacking one another for imperialist purposes.[212] Western communists acted accordingly; although they had previously supported collective security, they now denounced Britain and France for going to war.[211]

When anti-German demonstrations erupted in Prague, Czechoslovakia, the Comintern ordered the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia to employ all of its strength to paralyse "chauvinist elements".[212] Moscow soon forced the French Communist Party and the Communist Party of Great Britain to adopt anti-war positions. On 7 September, Stalin called Georgi Dimitrov,[clarification needed] who sketched a new Comintern line on the war that stated that the war was unjust and imperialist, which was approved by the secretariat of the Comintern on 9 September. Thus, western communist parties now had to oppose the war and to vote against war credits.[213] Although the French communists had unanimously voted in Parliament for war credits on 2 September and declared their "unshakeable will" to defend the country on 19 September, the Comintern formally instructed the party to condemn the war as imperialist on 27 September. By 1 October, the French communists advocated listening to German peace proposals, and leader Maurice Thorez deserted from the French Army on 4 October and fled to Russia.[214] Other communists also deserted from the army.

The Communist Party of Germany featured similar attitudes. In Die Welt, a communist newspaper published in Stockholm[f] the exiled communist leader Walter Ulbricht opposed the Allies, stated that Britain represented "the most reactionary force in the world",[216] and argued, "The German government declared itself ready for friendly relations with the Soviet Union, whereas the English–French war bloc desires a war against the socialist Soviet Union. The Soviet people and the working people of Germany have an interest in preventing the English war plan".[217]

Despite a warning by the Comintern, German tensions were raised when the Soviets stated in September that they must enter Poland to "protect" their ethnic Ukrainian and Belarusian brethren from Germany. Molotov later admitted to German officials that the excuse was necessary because the Kremlin could find no other pretext for the Soviet invasion.[218]

During the early months of the Pact, Soviet foreign policy became critical of the Allies and more pro-German in turn. During the Fifth Session of the Supreme Soviet on 31 October 1939, Molotov analysed the international situation, thus giving the direction for communist propaganda. According to Molotov, Germany had a legitimate interest in regaining its position as a great power, and the Allies had started an aggressive war in order to maintain the Versailles system.[219]

Expansion of raw materials and military trading

[edit]Germany and the Soviet Union entered an intricate trade pact on 11 February 1940 that was over four times larger than the one that the two countries had signed in August 1939.[220] The new trade pact helped Germany surmount a British blockade.[220] In the first year, Germany received one million tons of cereals, half-a-million tons of wheat, 900,000 tons of oil, 100,000 tons of cotton, 500,000 tons of phosphates and considerable amounts of other vital raw materials, along with the transit of one million tons of soybeans from Manchuria. Those and other supplies were being transported through Soviet and occupied Polish territories.[220] The Soviets were to receive a naval cruiser, the plans to the battleship Bismarck, heavy naval guns, other naval gear and 30 of Germany's latest warplanes, including the Bf 109 and Bf 110 fighters and Ju 88 bomber.[220] The Soviets would also receive oil and electric equipment, locomotives, turbines, generators, diesel engines, ships, machine tools, and samples of German artillery, tanks, explosives, chemical-warfare equipment, and other items.[220]

The Soviets also helped Germany to avoid British naval blockades by providing a submarine base, Basis Nord, in the northern Soviet Union near Murmansk.[212] That also provided a refueling and maintenance location and a takeoff point for raids and attacks on shipping.[212] In addition, the Soviets provided Germany with access to the Northern Sea Route for both cargo ships and raiders though only the commerce raider Komet used the route before the German invasion, which forced Britain to protect sea lanes in both the Atlantic and the Pacific.[221]

Summer deterioration of relations

[edit]The Finnish and Baltic invasions began a deterioration of relations between the Soviets and Germany.[222] Stalin's invasions were a severe irritant to Berlin since the intent to accomplish them had not been communicated to the Germans beforehand, and they prompted concern that Stalin was seeking to form an anti-German bloc.[223] Molotov's reassurances to the Germans only intensified the Germans' mistrust. On 16 June, as the Soviets invaded Lithuania but before they had invaded Latvia and Estonia, Ribbentrop instructed his staff "to submit a report as soon as possible as to whether in the Baltic States a tendency to seek support from the Reich can be observed or whether an attempt was made to form a bloc."[224]

In August 1940, the Soviet Union briefly suspended its deliveries under its commercial agreement after relations were strained after disagreements over policy in Romania, the Soviet war with Finland, Germany's falling behind on its deliveries of goods under the pact and Stalin's worry that Hitler's war with the West might end quickly after France signed an armistice.[225] The suspension created significant resource problems for Germany.[225] By the end of August, relations had improved again, as the countries had redrawn the Hungarian and Romanian borders and settled some Bulgarian claims, and Stalin was again convinced that Germany would face a long war in the west with Britain's improvement in its air battle with Germany and the execution of an agreement between the United States and Britain regarding destroyers and bases.[226]

In early September however, Germany arranged its own occupation of Romania, targeting its oil fields.[227] That move raised tensions with the Soviets, who responded that Germany was supposed to have consulted with the Soviet Union under Article III of the pact.[227]

German–Soviet Axis talks

[edit]

After Germany in September 1940 entered the Tripartite Pact with Japan and Italy, Ribbentrop wrote to Stalin, inviting Molotov to Berlin for negotiations aimed to create a 'continental bloc' of Germany, Italy, Japan, and the Soviet Union that would oppose Britain and the United States.[228] Stalin sent Molotov to Berlin to negotiate the terms for the Soviet Union to join the Axis and potentially to enjoy the spoils of the pact.[229][230] After negotiations during November 1940 on where to extend the Soviet sphere of influence, Hitler broke off talks and continued planning for the eventual attempts to invade the Soviet Union.[228][231]

Late relations

[edit]

In an effort to demonstrate peaceful intentions toward Germany, on 13 April 1941, the Soviets signed a neutrality pact with Japan, an Axis power.[232] While Stalin had little faith in Japan's commitment to neutrality, he felt that the pact was important for its political symbolism to reinforce a public affection for Germany.[233] Stalin felt that there was a growing split in German circles about whether Germany should initiate a war with the Soviet Union.[233] Stalin did not know that Hitler had been secretly discussing an invasion of the Soviet Union since summer 1940[234] and that Hitler had ordered his military in late 1940 to prepare for war in the East, regardless of the parties' talks of a potential Soviet entry as a fourth Axis power.[235]

Termination

[edit]

Germany unilaterally terminated the pact at 03:15 on 22 June 1941 by launching a massive attack on the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa.[122] Stalin had ignored repeated warnings that Germany was likely to invade[236][237][238] and ordered no "full-scale" mobilisation of forces although the mobilisation was ongoing.[239] After the launch of the invasion, the territories gained by the Soviet Union as a result of the pact were lost in a matter of weeks. The southeastern part was absorbed into Greater Germany's General Government, and the rest was integrated with the Reichskommissariats Ostland and Ukraine. Within six months, the Soviet military had suffered 4.3 million casualties,[240] and three million more had been captured.[241] The lucrative export of Soviet raw materials to Germany over the course of the economic relations continued uninterrupted until the outbreak of hostilities. The Soviet exports in several key areas enabled Germany to maintain its stocks of rubber and grain from the first day of the invasion to October 1941.[242]

Aftermath

[edit]

Discovery of the secret protocol

[edit]The German original of the secret protocols was presumably destroyed in the bombing of Germany,[243] but in late 1943, Ribbentrop had ordered the most secret records of the German Foreign Office from 1933 onward, amounting to some 9,800 pages, to be microfilmed. When the various departments of the Foreign Office in Berlin were evacuated to Thuringia at the end of the war, Karl von Loesch, a civil servant who had worked for the chief interpreter Paul Otto Schmidt, was entrusted with the microfilm copies. He eventually received orders to destroy the secret documents but decided to bury the metal container with the microfilms as personal insurance for his future well-being. In May 1945, von Loesch approached the British Lieutenant Colonel Robert C. Thomson with the request to transmit a personal letter to Duncan Sandys, Churchill's son-in-law. In the letter, von Loesch revealed that he had knowledge of the documents' whereabouts but expected preferential treatment in return. Thomson and his American counterpart, Ralph Collins, agreed to transfer von Loesch to Marburg, in the American zone if he would produce the microfilms. The microfilms contained a copy of the Non-Aggression Treaty as well as the Secret Protocol.[244] Both documents were discovered as part of the microfilmed records in August 1945 by US State Department employee Wendell B. Blancke, the head of a special unit called "Exploitation German Archives" (EGA).[245]

News of the secret protocols first appeared during the Nuremberg trials. Alfred Seidl, the attorney for defendant Hans Frank, was able to place into evidence an affidavit that described them. It was written from memory by Nazi Foreign Office lawyer Friedrich Gaus, who wrote the text and was present at its signing in Moscow. Later, Seidl obtained the German-language text of the secret protocols from an anonymous Allied source and attempted to place them into evidence while he was questioning witness Ernst von Weizsäcker, a former Foreign Office State Secretary. The Allied prosecutors objected, and the texts were not accepted into evidence, but Weizsäcker was permitted to describe them from memory, thus corroborating the Gaus affidavit. Finally, at the request of a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter, American deputy prosecutor Thomas J. Dodd acquired a copy of the secret protocols from Seidl and had it translated into English. They were first published on 22 May 1946 in a front-page story in that newspaper.[246] Later, in Britain, they were published by The Manchester Guardian.

The protocols gained wider media attention when they were included in an official State Department collection, Nazi–Soviet Relations 1939–1941, edited by Raymond J. Sontag and James S. Beddie and published on 21 January 1948. The decision to publish the key documents on German–Soviet relations, including the treaty and protocol, had been taken already in spring 1947. Sontag and Beddie prepared the collection throughout the summer of 1947. In November 1947, President Harry S. Truman personally approved the publication, but it was held back in view of the Foreign Ministers Conference in London scheduled for December. Since negotiations at that conference did not prove to be constructive from an American point of view, the document edition was sent to press. The documents made headlines worldwide.[247] State Department officials counted it as a success: "The Soviet Government was caught flat-footed in what was the first effective blow from our side in a clear-cut propaganda war."[248]

Despite publication of the recovered copy in western media, for decades, the official policy of the Soviet Union was to deny the existence of the secret protocol.[249] The secret protocol's existence was officially denied until 1989. Vyacheslav Molotov, one of the signatories, went to his grave categorically rejecting its existence.[250] The French Communist Party did not acknowledge the existence of the secret protocol until 1968, as the party de-Stalinized.[214]

On 23 August 1986, tens of thousands of demonstrators in 21 western cities, including New York, London, Stockholm, Toronto, Seattle, and Perth participated in Black Ribbon Day Rallies to draw attention to the secret protocols.[251]

Stalin's "Falsifiers of History" and Axis negotiations

[edit]In response to the publication of the secret protocols and other secret German–Soviet relations documents in the State Department edition Nazi–Soviet Relations (1948), Stalin published Falsifiers of History, which included the claim that during the pact's operation, Stalin rejected Hitler's claim to share in a division of the world,[252] without mentioning the Soviet offer to join the Axis. That version persisted, without exception, in historical studies, official accounts, memoirs, and textbooks published in the Soviet Union until the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[252]

The book also claimed that the Munich agreement was a "secret agreement" between Germany and "the west" and a "highly important phase in their policy aimed at goading the Hitlerite aggressors against the Soviet Union."[253][254]

Denial of the secret protocol

[edit]For decades, it was the official policy of the Soviet Union to deny the existence of the secret protocol to the Soviet–German Pact. At the behest of Mikhail Gorbachev, Alexander Nikolaevich Yakovlev headed a commission investigating the existence of such a protocol. In December 1989, the commission concluded that the protocol had existed and revealed its findings to the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union.[243] As a result, the Congress passed the declaration confirming the existence of the secret protocols and condemning and denouncing them.[255][256] The Soviet government thus finally acknowledged and denounced the Secret Treaty[257] and Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Head of State condemned the pact. Vladimir Putin condemned the pact as "immoral" but also defended it as a "necessary evil".[258][259] At a press conference on 19 December 2019, Putin went further and announced that the signing of the pact was no worse than the 1938 Munich Agreement, which led to the partition of Czechoslovakia.[260][261]

Both successor states of the pact parties have declared the secret protocols to be invalid from the moment that they were signed: the Federal Republic of Germany on 1 September 1989 and the Soviet Union on 24 December 1989,[262] following an examination of the microfilmed copy of the German originals.[263]

The Soviet copy of the original document was declassified in 1992 and published in a scientific journal in early 1993.[263]

In August 2009, in an article written for the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza, Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin condemned the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact as "immoral".[264][265]

The new Russian nationalists and revisionists, including Russian negationist Aleksandr Dyukov and Nataliya Narotchnitskaya, whose book carried an approving foreword by the Russian foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, described the pact as a necessary measure because of the British and French failure to enter into an antifascist pact.[257]

Postwar commentary on motives of Stalin and Hitler

[edit]Some scholars believe that, from the very beginning of the Tripartite negotiations between the Soviet Union, Great Britain and France, the Soviets clearly required the other parties to agree to a Soviet occupation of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania,[52] and for Finland to be included in the Soviet sphere of influence.[266]

On the timing of German rapprochement, many historians agree that the dismissal of Maxim Litvinov, whose Jewish ethnicity was viewed unfavourably by Nazi Germany, removed an obstacle to negotiations with Germany.[71][267][268][269][270][271][272][273] Stalin immediately directed Molotov to "purge the ministry of Jews."[274][270][275] Given Litvinov's prior attempts to create an anti-fascist coalition, association with the doctrine of collective security with France and Britain and a pro-Western orientation[276] by the standards of the Kremlin, his dismissal indicated the existence of a Soviet option of rapprochement with Germany.[277][g] Likewise, Molotov's appointment served as a signal to Germany that the Soviet Union was open to offers.[277] The dismissal also signaled to France and Britain the existence of a potential negotiation option with Germany.[49][278] One British official wrote that Litvinov's termination also meant the loss of an admirable technician or shock-absorber but that Molotov's "modus operandi" was "more truly Bolshevik than diplomatic or cosmopolitan."[279] Carr argued that the Soviet Union's replacement of Litvinov with Molotov on 3 May 1939 indicated not an irrevocable shift towards alignment with Germany but rather was Stalin's way of engaging in hard bargaining with the British and the French by appointing a proverbial hard man to the Foreign Commissariat.[280] Historian Albert Resis stated that the Litvinov dismissal gave the Soviets freedom to pursue faster German negotiations but that they did not abandon British–French talks.[281] Derek Watson argued that Molotov could get the best deal with Britain and France because he was not encumbered with the baggage of collective security and could negotiate with Germany.[282] Geoffrey Roberts argued that Litvinov's dismissal helped the Soviets with British–French talks because Litvinov doubted or maybe even opposed such discussions.[283]

E. H. Carr stated: "In return for 'non-intervention' Stalin secured a breathing space of immunity from German attack."[284] According to Carr, the "bastion" created by means of the pact "was and could only be, a line of defense against potential German attack."[285] According to Carr, an important advantage was that "if Soviet Russia had eventually to fight Hitler, the Western Powers would already be involved."[285][286] However, during the last decades, that view has been disputed. Historian Werner Maser - who served the German army during the second World War[287] - stated that "the claim that the Soviet Union was at the time threatened by Hitler, as Stalin supposed ... is a legend, to whose creators Stalin himself belonged.[288] In Maser's view, "neither Germany nor Japan were in a situation [of] invading the USSR even with the least perspective [sic] of success," which must not have been known to Stalin.[289] Carr further stated that for a long time, the primary motive of Stalin's sudden change of course was assumed to be the fear of German aggressive intentions.[290] On the other hand, Soviet-born Australian historical writer Alex Ryvchin characterized the pact as "a Soviet deal with the devil, which contained a secret protocol providing for the remaining independent states of East-Central Europe to be treated as courses on some debauched degustation menu for two of the greatest monsters in history."[291]

Many Polish newspapers published numerous articles claiming that Russia must apologise to Poland for the pact.[292]

Two weeks after Soviet armies had entered the Baltic states, Berlin requested Finland to permit the transit of German troops, and five weeks later Hitler issued a secret directive "to take up the Russian problem, to think about war preparations," a war whose objective would include establishment of a Baltic confederation.[293]

A number of German historians have debunked the claim that Operation Barbarossa was a preemptive strike, such as Andreas Hillgruber, Rolf-Dieter Müller, and Christian Hartmann, but they also acknowledge that the Soviets were aggressive to their neighbors.[294][295][296]

According to Stalin's daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva she "remembered her father saying after [the war]: 'Together with the Germans we would have been invincible'."[297]

Russian Trotskyist historian, Vadim Rogovin argued that Stalin had destroyed thousands of foreign communists capable of leading socialist change in their respective countries. He referenced the thousands of German communists that were handed over from Stalin to the Gestapo after the signing of the German-Soviet pact. Rogovin also noted that sixteen members of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party became victims of Stalinist terror.[298] Similarly, historian Eric D. Weitz discussed the areas of collaboration between the regimes in which hundreds of German citizens, the majority of whom were Communists, had been handed over to the Gestapo from Stalin's administration. Weitz also stated that a higher proportion of the KPD Politburo members had died in the Soviet Union than in Nazi Germany.[299] However, according to the work of Wilhelm Mensing, there is no evidence which suggests that the Soviets specifically targeted German and Austrian Communists or others who perceived themselves as "anti-fascists" for deportations to Nazi Germany.[300]

Remembrance and response

[edit]The pact was a taboo subject in the postwar Soviet Union.[301] In December 1989, the Congress of People's Deputies of the Soviet Union condemned the pact and its secret protocol as "legally deficient and invalid".[302] In modern Russia, the pact is often portrayed positively or neutrally by the pro-government propaganda; for example, Russian textbooks tend to describe the pact as a defensive measure, not as one aiming at territorial expansion.[301] In 2009, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that "there are grounds to condemn the Pact",[303] but described it in 2014 as "necessary for Russia's survival".[304][305] Accusations that cast doubt on the positive portrayal of the USSR's role in World War II have been seen as highly problematic for the modern Russian state, which sees Russia's victory in the war as one of "the most venerated pillars of state ideology", which legitimises the current government and its policies.[306][307] In February 2021, the State Duma voted in favor of a law to punish the dissemination of "fake news" regarding the Soviet Union's role in World War II, including claiming that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union held equal responsibility due to the pact.[308]

In 2009, the European Parliament proclaimed 23 August, the anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, as the European Day of Remembrance for Victims of Stalinism and Nazism, to be commemorated with dignity and impartiality.[309] In connection with the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe parliamentary resolution condemned both communism and fascism for starting World War II and called for a day of remembrance for victims of both Stalinism and Nazism on 23 August.[310] In response to the resolution, Russian lawmakers threatened the OSCE with "harsh consequences".[310][311] A similar resolution was passed by the European Parliament a decade later, blaming the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop pact for the outbreak of war in Europe and again leading to criticism by Russian authorities.[306][307][312]

See also

[edit]- Baltic Way, protest marking the 50th anniversary of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

- Italo-Soviet Pact

- German–Soviet population transfers

- National Bolshevism

- Red–green–brown alliance

- Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact

- Stalin's speech of 19 August 1939

- Timeline of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact

- Walter Krivitsky, Soviet defector who revealed plans of the non-aggression pact before World War II

Notes

[edit]- ^ Russian: Пакт Молотова-Риббентропа; German: Molotow-Ribbentrop-Pakt

- ^ Russian: Договор о Ненападении между Германией и Союзом Советских Социалистических Республик; German: Nichtangriffsvertrag zwischen Deutschland und der Union der Sozialistischen Sowjetrepubliken

- ^ To 53 million ℛ︁ℳ︁ in German imports (0.9% of Germany's total imports and 6.3% of Russia's total exports) and 34 million ℛ︁ℳ︁ in German exports (0.6% of Germany's total exports and 4.6% of Russia's total imports) in 1938.[23]

- ^ On 28 July, Molotov sent a political instruction to the Soviet ambassador in Berlin that marked the start of secret Soviet–German political negotiations.[77]

- ^ The actual number of deported in the period of 1939–1941 remains unknown and various estimates vary from 350,000[202] to over 2 million, mostly World War II estimates by the underground. The earlier number is based on records made by the NKVD and does not include roughly 180,000 prisoners of war, who were also in Soviet captivity. Most modern historians estimate the number of all people deported from areas taken by Soviet Union during that period at between 800,000 and 1,500,000;[203][204] for example, RJ Rummel gives the number of 1,200,000 million;[205] Tony Kushner and Katharine Knox give 1,500,000.[206]

- ^ Having been banned in Stockholm, it continued to be published in Zürich.[215]

- ^ According to Paul Flewers, Stalin's address to the eighteenth congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 10 March 1939, discounted any idea of German designs on the Soviet Union. Stalin had intended: "To be cautious and not allow our country to be drawn into conflicts by warmongers who are accustomed to have others pull the chestnuts out of the fire for them." This was intended to warn the Western powers that they could not necessarily rely upon the support of the Soviet Union.[213]

References

[edit]- ^ "Faksimile Nichtangriffsvertrag zwischen Deutschland und der Union der Sozialistischen Sowjetrepubliken, 23. August 1939 / Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB, München)". 1000dokumente.de. Archived from the original on 2 May 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- ^ Ronen, Yaël (19 May 2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes under International Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. xix. ISBN 978-1-139-49617-9.

- ^ Schwendemann, Heinrich (1995). "German-Soviet Economic Relations at the Time of the Hitler-Stalin pact 1939-1941". Cahiers du Monde russe. 36 (1/2): 161–178. doi:10.3406/cmr.1995.2425. ISSN 1252-6576. JSTOR 20170949. Archived from the original on 21 December 2020. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ a b "See Secret in Accord: Dr. Harper Says Stalin-Hitler Pact May Prove an Alliance". New York Times. 28 August 1939. p. 11. Archived from the original on 22 September 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Doerr, Paul W. (1 July 2001). "'Frigid but Unprovocative': British Policy towards the USSR from the Nazi-Soviet Pact to the Winter War, 1939". Journal of Contemporary History. 36 (3): 423–439. doi:10.1177/002200940103600302. ISSN 0022-0094. S2CID 159616101.

- ^ "German-Soviet Nonaggression Pact | History, Facts, & Significance | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 23 October 2024. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- ^ Zabecki, David (2014). Germany at war : 400 years of military history. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 536. ISBN 978-1-59884-981-3.

- ^ Senn, Alfred (January 1990). "Perestroika in Lithuanian Historiography: The Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact". The Russian Review. 49 (1): 44–53. doi:10.2307/130082. JSTOR 130082.

- ^ Goldman 2012, pp. 163–64.

- ^ Collier, Martin, and Pedley, Philip Germany 1919–45 (2000) p. 146

- ^ Brackman, Roman The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life (2001) p. 341

- ^ "German-Soviet Pact". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- ^ "Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk". BYU. 3 March 1918. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 21 January 2009..

- ^ Montefiore 2005, p. 32.

- ^ "German–Russian agreement". Rapallo: Mt Holyoke. 16 April 1922. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 7 February 2009..

- ^ "Treaty of Berlin Between the Soviet Union and Germany". Yale. 24 April 1926. Archived from the original on 31 March 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2009..

- ^ a b Ericson 1999, pp. 14–5.

- ^ Bendersky 2000, p. 177.

- ^ Lee, Stephen J; Paul, Shuter (1996). Weimar and Nazi Germany. Heinemann. p. 33. ISBN 0-435-30920-X..

- ^ Bendersky 2000, p. 159.

- ^ Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd R (2002). Hitler's War in the East, 1941–1945: A Critical Assessment. Berghahn. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-57181-293-3..

- ^ Kershaw, Ian (17 April 2000). Hitler: 1889-1936 Hubris. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-25420-4.

- ^ Ericson, Edward E III (May 1998). "Karl Schnurre and the Evolution of Nazi–Soviet Relations, 1936–1941". German Studies Review. 21 (2): 263–83. doi:10.2307/1432205. JSTOR 1432205.

- ^ Hehn 2005, p. 212.

- ^ Weinberg, Gerhard L. (1 March 2010). Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933-1939: The Road to World War II. Enigma Books. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-936274-84-0. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ Jurado, Carlos Caballero; Bujeiro, Ramiro (2006). The Condor Legion: German Troops in the Spanish Civil War. Osprey. pp. 5–6. ISBN 1-84176-899-5.

- ^ Lind, Michael (2002). Vietnam, the Necessary War: A Reinterpretation of America's Most Disastrous Military Conflict. Simon & Schuster. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-684-87027-4.

- ^ Gerhard, Weinberg (1970). The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Diplomatic Revolution in Europe 1933–36. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 346.

- ^ Spector, Robert Melvin. World Without Civilization: Mass Murder and the Holocaust, History, and Analysis. p. 257.

- ^ "Italy and Soviet Sign Treaty". nytimes.com. New York Times. Retrieved 15 October 2024.

- ^ Roger, Moorhouse (7 January 2016). The devils' alliance: Hitler's pact with Stalin, 1939-41. London. ISBN 9780099571896. OCLC 934937192.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[page needed] - ^ "Hitler and Russia". The Times. London. 24 June 1941..

- ^ "Agreement concluded at between Germany, Great Britain, France and Italy". Munich: Yale. 29 September 1938.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kershaw 2001, pp. 157–8.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 124.

- ^ Beloff, Max (October 1950). "Soviet Foreign Policy, 1929–41: Some Notes". Soviet Studies. 2 (2): 123–137. doi:10.1080/09668135008409773.

- ^ Kershaw 2001, p. 194.

- ^ Carr 1949a, 1949b

- ^ a b Ericson 1999, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Ericson 1999, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Ericson 1999, pp. 29–35.

- ^ Hehn 2005, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Ericson 1999, p. 44.

- ^ Collier, Martin; Pedley, Philip. Germany, 1919–45..

- ^ Kinder, Hermann; Hilgemann, Werner (1978). The Anchor Atlas of World History. Vol. II. New York: Anchor Press, Doubleday. p. 165. ISBN 0-385-13355-3.

- ^ Crozier, Andrew J. The Causes of the Second World War. p. 151..

- ^ Brown, Robert J (1 January 2004). Manipulating the Ether: The Power of Broadcast Radio in Thirties America. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2066-9..

- ^ Carley 1993.

- ^ a b c d Watson 2000, pp. 696–8.

- ^ a b c d Roberts 2006, p. 30.

- ^ "Tentative Efforts To Improve German–Soviet Relations, April 17 – August 14, 1939". Yale. Archived from the original on 11 February 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2012..

- ^ a b Grogin, Robert C (2001). Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War, 1917–1991. Lexington. p. 28..

- ^ Carley 1993, p. 324.

- ^ a b Watson 2000, p. 695.

- ^ Roberts, G (December 1997). "Review of Raack, R, Stalin's Drive to the West, 1938–1945: The Origins of the Cold War". The Journal of Modern History. 69 (4): 787..

- ^ Watt 1989, p. 118.

- ^ Carley 1993, pp. 303–41.

- ^ a b Watson 2000, p. 696.

- ^ Watson 2000, p. 704.

- ^ Carley 1993, pp. 322–3.

- ^ Watson 2000, p. 708.

- ^ a b Shirer 1990, p. 502.

- ^ Hiden, John (2003). The Baltic and the Outbreak of the Second World War. Cambridge University Press. p. 46. ISBN 0-521-53120-9..

- ^ Watson 2000, pp. 710–1.

- ^ Gromyko, Andrei; Ponomarev, B. N. Ponomarev (1981). Soviet foreign policy : 1917-1980 Collectible Soviet foreign policy : 1917-1980. Progressive Publishers. p. 89. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 18 January 2018..

- ^ Butler, Susan (2016). Roosevelt and Stalin: Portrait of a Partnership. Vintage Books. p. 173. ISBN 9780307741813..

- ^ Nekrich, Ulam & Freeze 1997, pp. 107–11.

- ^ Gerhard L. Weinberg (2010). Hitler's Foreign Policy 1933-1939: The Road to World War II. Enigma Books. p. 749. ISBN 9781936274840. Archived from the original on 29 July 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Ericson 1999, p. 46.

- ^ P. Tsygankov, Andrei (2012). Russia and the West from Alexander to Putin: Honor in International Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-1139537001. Archived from the original on 29 July 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b Nekrich, Ulam & Freeze 1997, pp. 109–10.

- ^ a b Roger, Moorhouse (7 January 2016). The devils' alliance: Hitler's pact with Stalin, 1939-41. London. ISBN 9780099571896. OCLC 934937192.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fest 2002, p. 588.

- ^ Ulam 1989, pp. 509–10.

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 503.

- ^ Roberts 1992a, p. 64.

- ^ Roberts 1992a, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Ericson 1999, pp. 54–5.

- ^ Ericson 1999, p. 56.

- ^ Nekrich, Ulam & Freeze 1997, p. 115.

- ^ Fest 2002, pp. 589–90.

- ^ Bertriko, Jean-Jacques; Subrenat, A; Cousins, David (2004). Estonia: Identity and Independence. Rodopi. p. 131. ISBN 90-420-0890-3..

- ^ "Hitler and Stalin Weren't Such Strange Bedfellows". The Wall Street Journal. 22 August 2019. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- ^ Watson 2000, p. 713.

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 536.

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 537.

- ^ Cienciala, Anna M (2006) [2004]. "The Coming of the War and Eastern Europe in World War II" (lecture notes). University of Kansas. Archived from the original on 1 August 2012. Retrieved 16 July 2009..

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 525.

- ^ Watson 2000, p. 715.

- ^ Murphy, David E (2006). What Stalin Knew: The Enigma of Barbarossa. Yale University Press. p. 23. ISBN 0-300-11981-X..

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 528.

- ^ Tolischus, Otto D. (25 August 1939). "Nazi Talks Secret: Hitler Lays Plans with His Close Aides for the Partition of Poland". New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Byas, Hugh (26 August 1939). "Japanese Protest Hitler-Stalin Pact". New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Paris Communists Stunned by Accord". New York Times. 26 August 1939. p. 2. Archived from the original on 3 June 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Tolischus, Otto D. (26 August 1939). "Berlin Talks Held: Nazi Quarters Now Feel General European war Has Been Averted". New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Polish Made Easy for Reich Troops: Booklet on Sale Has Phonetic Aid—'Good Day, Mr. Mayor' Is the Opening Phrase: Gleiwitz Fears Raids". New York Times. 28 August 1939. p. 2. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Soviet Fails to Act on Pact With Reich". New York Times. 28 August 1939. p. 1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ "Russian Massing Soldiers in West". New York Times. 30 August 1939. p. 1. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

- ^ Watt 1989, p. 367.

- ^ Media build up to World War II Archived 21 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News, 24 August 2009

- ^ a b c d e "Text of the Nazi–Soviet Non-Aggression Pact". Fordham. 23 August 1939. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 11 February 2003..

- ^ Ceslovas Laurinavicius, "The Lithuanian Reaction to the Loss of Klaipeda and the Combined Gift of Soviet "Security Assistance and Vilnius", in: Northern European Overture to War, 1939–1941: From Memel to Barbarossa, 2013, ISBN 90-04-24909-5

- ^ Christie, Kenneth (2002). Historical Injustice and Democratic Transition in Eastern Asia and Northern Europe: Ghosts at the Table of Democracy. RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 0-7007-1599-1..

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 539.

- ^ Shirer 1990, p. 540.

- ^ a b c d Gunther, John (1940). Inside Europe. New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 137–138.

- ^ van Dijk, Ruud, ed. (2008). Encyclopedia of the Cold War. London: Routledge. p. 597. ISBN 978-0-415-97515-5..

- ^ Wegner 1997, p. 507.

- ^ Dębski, Sławomir (2007). Między Berlinem a Moskwą. Stosunki niemiecko-sowieckie 1939–1941. Warszawa: Polski Instytut SprawMiędzynarodowych. ISBN 978-83-89607-08-9..

- ^ Dunn, Dennis J (1998). Caught Between Roosevelt & Stalin: America's Ambassadors to Moscow. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 124–5. ISBN 0-8131-2023-3..

- ^ "Moscow's Week". Time. 9 October 1939. Archived from the original on 31 March 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009..

- ^ "Revival". Time. 9 October 1939. Archived from the original on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2009..

- ^ "Communazi Columnists". Time. 3 June 1940. Archived from the original on 28 February 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2009..

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (6 January 1941). "The Revolt of the Intellectuals". Time. Archived from the original on 3 December 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ "In Again, Out Again". Time. 7 April 1941. Archived from the original on 31 March 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009..

- ^ Sheen, Fulton John (1948). Communism and the Conscience of the West. Bobbs–Merrill. p. 115..