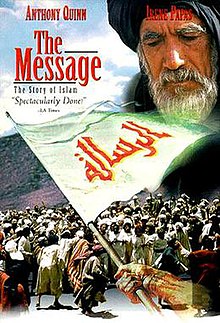

The Message (1976 film)

| The Message | |

|---|---|

DVD cover | |

| Directed by | Moustapha Akkad |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Muhammad |

| Produced by | Moustapha Akkad |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jack Hildyard |

| Edited by | John Bloom |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

Production company | Filmco International Productions Inc. |

| Distributed by | Tarik Film Distributors |

Release dates | |

Running time |

|

| Countries | Lebanon Libya Kuwait Morocco United Kingdom |

| Languages | Arabic English |

| Budget | $17 million |

| Box office | $5 million |

The Message (Arabic: الرسالة, Ar-Risālah; originally known as Mohammad, Messenger of God) is a 1976 epic film directed and produced by Moustapha Akkad that chronicles the life and times of Muhammad, who is never directly depicted.[4]

Released in separately filmed Arabic- and English-language versions, The Message serves as an introduction to the early history of Islam. The international ensemble cast includes Anthony Quinn, Irene Papas, Michael Ansara, Johnny Sekka, Michael Forest, André Morell, Garrick Hagon, Damien Thomas, and Martin Benson. It was an international co-production between Libya, Morocco, Lebanon, Syria and the UK.

The film was nominated for Best Original Score in the 50th Academy Awards, composed by Maurice Jarre, but lost the award to Star Wars (composed by John Williams).

Plot

[edit]The film begins with Muhammad sending an invitation to accept Islam to the surrounding rulers: Heraclius, the Byzantine Emperor; Muqawqis, the Patriarch of Alexandria; Kisra, the Sasanian Emperor.

Earlier, Muhammad is visited by the angel Gabriel, which shocks him deeply. The angel asks him to start and spread the Quran. Gradually, a small number of people in the city of Mecca begin to convert. As a result, more enemies will come and hunt Muhammad and his companions from Mecca and confiscate their possessions. Some of these followers fled to Abyssinia to seek refuge with the protection given by the king there.

They head north, where they receive a warm welcome in the city of Medina and build the first Islamic mosque. They are told that their possessions are being sold in Mecca on the market. Muhammad chooses peace for a moment, but still gets permission to attack. They are attacked but win the Battle of Badr. The Meccans, desiring revenge, fight back with three thousand men in the Battle of Uhud, killing Hamza. The Muslims run after the Meccans and leave the camp unprotected. Because of this, they are surprised by riders from behind, so they lose the battle. The Meccans and the Muslims close a 10-year truce.

A few years later, Khalid ibn Walid, a Meccan general who has killed many Muslims, converts to Islam. Meanwhile, Muslim camps in the desert are attacked in the night. The Muslims believe that the Meccans are responsible. Abu Sufyan comes to Medina fearing retribution and claiming that it was not the Meccans, but robbers who had broken the truce. None of the Muslims give him an audience, claiming he "observes no treaty and keeps no pledge". The Muslims respond with an attack on Mecca with many troops and "men from every tribe".

Abu Sufyan seeks an audience with Muhammad on the eve of the attack. The Meccans become very scared but are reassured that people in their houses, by the Kaaba, or in Abu Sufyan's house will be safe. They surrender and Mecca falls into the hands of the Muslims without bloodshed. The pagan images of the gods in the Kaaba are destroyed, and the very first azan in Mecca is called on the Kaaba by Bilal ibn Rabah. The Farewell Sermon is also delivered.

The film ends with the narrator discussing the legacy of Islam, followed by actual footage of worshippers making tawaf around the Kaaba in recent times. The end credits feature a montage of footage from various mosques around the world as the adhan echoes throughout them all and Muslims gather to pray in congregation.

Cast

[edit]- English version

- Anthony Quinn as Hamza

- Irene Papas as Hind bint Utbah

- Michael Ansara as Abu Sufyan ibn Harb

- Johnny Sekka as Bilal ibn Rabah

- Michael Forest as Khalid ibn al-Walid

- André Morell as Abu Talib

- Garrick Hagon as Ammar ibn Yasir

- Damien Thomas as Zayd

- Martin Benson as Abu Jahl

- Robert Brown as Utbah ibn Rabi'ah

- Rosalie Crutchley as Sumayyah

- Bruno Barnabe as Umayyah ibn Khalaf

- Neville Jason as Ja`far ibn Abī Tālib

- John Bennett as Salul

- Donald Burton as 'Amr ibn al-'As

- Earl Cameron as Al-Najashi

- George Camiller as Walid ibn Utbah

- Nicholas Amer as Suhayl ibn Amr

- Ronald Chenery as Mus`ab ibn `Umair

- Michael Godfrey as Baraa'

- John Humphry as Ubaydah

- Ewen Solon as Yasir

- Wolfe Morris as Abu Lahab

- Ronald Leigh-Hunt as Heraclius

- Leonard Trolley as Silk Merchant

- Gerard Hely as Poet Sinan

- Habib Ageli as Hudhayfah

- Peter Madden as Toothless Man

- Hassan Joundi as Khosrau II

- Abdullah Lamrani as Ikrimah

- Elaine Ives-Cameron as Arwa

Arabic version

- Abdullah Gaith as Hamza

- Muna Wassef as Hind

- Hamdi Ghaith as Abu Sufyan ibn Harb

- Sanaa Gamil as Sumayyah bint Khabbat

- Ali Ahmed Salem as Bilal

- Mahmoud Said as Khalid

- Ahmad Marey as Zayd

- Mohammad Larbi as Ammar

- Hassan Joundi as Abu Jahl

- Martin Benson as Khosrau II

- Damien Thomas as Young Christian

Production

[edit]

The scholars and historians of Islam -

The University of Al-Azhar in Cairo

The High Islamic Congress of the Shiat in Lebanon

have approved the accuracy and fidelity of this film.

The makers of this film honor the Islamic tradition

which holds that the impersonation of the prophet

offends against the spirituality of his message.

Therefore, the person of Mohammad

will not be shown.

Moustapha Akkad considered creating a film about Muhammad and the birth of Islam in 1967.[5] The film's script, written by H.A.L. Craig, was approved in its entirety by Tawfiq al-Hakim, a scholar at Al-Azhar University.[6] However, the film's approval was revoked and referred to as "an insult to Islam".[7] Ahmed Asmat Abdel-Meguid and Mowaffak Allaf, the permanent representatives to the United Nations for Egypt and Syria, praised the film for its depiction of Islam.[8] While creating The Message, director Akkad, who was Muslim, consulted Islamic clerics in a thorough attempt to be respectful towards Islam and its views on portraying Muhammad. It was rejected by the Muslim World League in Mecca, Saudi Arabia.[citation needed]

$10 million was raised for the film from Kuwait, Libya, Morocco, Saudi Arabia and the United States and it had a final budget of $17 million. Akkad started filming in 1974, with a crew of 300, 40 actors for both English and Arabic language versions, and over 5,000 people for crowd shots. A $700,000 replica of Mecca was built near Marrakesh and Anthony Quinn was paid $1.5 million according to Michael Ansara.[9][6][10] Muhammad Ali wanted to play Bilal, but the role was given to Sekka instead with Sekka stating that "Akkad wanted a Moslem with acting experience to play the role" and "how could anyone believe that Ali could be tortured and abused as Bilal was?".[11]

Filming in Morocco started in April 1974, but Moroccan police forced them to stop filming on 5 August, as Hassan II of Morocco had been pressured by Faisal of Saudi Arabia. Akkad was granted permission to film in Libya after showing unedited film to Muammar Gaddafi and filmed from October 1974 to May 1975. Gaddafi wanted Akkad to also make a film based on the life of Omar al-Mukhtar.[6][12][9] Akkad filmed the English and Arabic versions of the film simultaneously with different actors.[13]

A light bulb on the camera was used during the scenes of characters with Muhammad to represent his immanence.[6] Islamic scholar Khaled Abou El Fadl, who was a friend of Akkad, praised his depiction of Muhammad stating that "To figure out a way to have the prophet become a person without showing him — it was brilliant".[7]

Akkad saw the film as a way to bridge the gap between the Western and Islamic worlds, stating in a 1976 interview:

I did the film because it is a personal thing for me. Besides its production values as a film, it has its story, its intrigue, its drama. Besides all this I think there was something personal, being a Muslim myself who lived in the west I felt that it was my obligation my duty to tell the truth about Islam. It is a religion that has a 700 million following, yet it's so little known about which surprised me. I thought I should tell the story that will bring this bridge, this gap to the west.[citation needed]

Release

[edit]In July 1976, five days before the film opened in London's West End, threatening phone calls to a cinema prompted Akkad to change the title from Mohammed, Messenger of God to The Message, at a cost of £50,000.[14][15] The film was banned in Egypt, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia.[7] Irwin Yablans distributed the film in the United States.[16]

As the film was scheduled to premiere in the United States, a splinter group of the black nationalist Nation of Islam calling itself the Hanafi Movement staged a siege of the Washington, D.C. chapter of the B'nai B'rith.[17] Under the mistaken belief that Anthony Quinn played Muhammad in the film,[18] the group threatened to blow up the building and its inhabitants unless the film's opening was cancelled.[17][18] The movie was pulled from theaters on the day of its premiere, but resumed playing after the siege ended.[19][20] Akkad offered to show the film to the Hanafi Muslims and said that he would destroy the film if they found it offensive.[21] The standoff was resolved after the deaths of a journalist and a policeman,[citation needed] but "the film's American box office prospects never recovered from the unfortunate controversy."[18]

An Indian Hindi-Urdu dub was released across the country in December 2007, it was produced by Yamshi Ahmed and Saad Ahmed under the Oasis Enterprises banner and was distributed by Anuj Saxena's Maverick Productions with scripting of the dub by Hasan Kamal. The dub also featured a redone soundtrack notably featuring the song "Marhaba Mustapha" by A. R. Rahman. Its release in India was approved by Maulana Kalbe Sadiq, the Vice President All India Muslim Personal Law Board and other Indian ulema.[22] Though it still faced opposition in Hyderabad, during its release there in February 2008 at the Rama Krishna Theatre, by the local Islamic group Tanzeem Islah-e-Muashra and the Islamic political party Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen - whose floor leader of the Andhra Pradesh Legislative Assembly Akbaruddin Owaisi sought a ban on the film for allegedly portraying Islam in a bad light. While this resulted in the stoppage of the film's exhibition in the city, distributor Maverick Productions defended the film saying that it contains no objectionable scenes but they were willing to cut any scenes deemed offensive.[23]

A 4K resolution restoration of the film was shown at the Dubai International Film Festival in December 2017, and it was given a theatrical release in Saudi Arabia.[24]

Reception

[edit]The film needed to gross $35 million to break even, but only earned $5 million during its theatrical run, with $2 million coming from the United States.[25]

Sunday Times film critic Dilys Powell described the film as a "Western … crossed with Early Christian". She noted a similar avoidance of direct depictions of Jesus in early biblical films, and suggested that "from an artistic as well as a religious point of view the film is absolutely right".[26] Variety praised the "stunning" photography, "superbly rendered" battle scenes and the "strong and convincing" cast, though the second half of the film was called "facile stuff and anticlimactic."[27] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times thought the battle scenes were "spectacularly done" and that Anthony Quinn's "dignity and stature" were right for his role.[28] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave it two stars out of four, calling it "a decent, big-budget religious movie. No more, no less."[29] Alexander Walker, writing for the Evening Standard, praised the film and said that "I found myself wholly absorbed by it".[30] Bob Thomas, writing in the Associated Press, stated that the film "is a reverent, plodding (three hours) ultimately rewarding epic of the birth of Islam".[31]

Richard Eder of The New York Times described the effect of not showing Muhammad as "awkward" and likened it to "one of those Music Minus One records," adding that the acting was "on the level of crudity of an early Cecil B. DeMille Bible epic, but the direction and pace is far more languid."[32] John Pym of The Monthly Film Bulletin wrote: "The unalleviated tedium of this ten-million dollar enterprise (billed as the first 'petrodollar' movie) is largely due to the tawdry staginess of all the sets and the apparent inability of Moustapha Akkad ... to muster larger groups of people on any but two-dimensional planes."[33] Derek Malcolm, writing for The Guardian, criticized the film for its length.[30]

Muna Wassef's role as Hind in the Arabic-language version won her international recognition.[34]

Awards and nominations

[edit]The film was nominated for an Oscar in 1977 for Best Original Score for the music by Maurice Jarre.[35]

Music

[edit]The musical score of The Message was composed and conducted by Maurice Jarre and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra.

- Track listing for the first release on LP

Side One

- The Message (3:01)

- Hegira (4:24)

- Building the First Mosque (2:51)

- The Sura (3:34)

- Presence of Mohammad (2:13)

- Entry to Mecca (3:15)

Side Two

- The Declaration (2:38)

- The First Martyrs (2:27)

- Fight (4:12)

- Spread of Islam (3:16)

- Broken Idols (4:00)

- The Faith of Islam (2:37)

- Track listing for the first release on CD

- The Message (3:09)

- Hegira (4:39)

- Building the First Mosque (2:33)

- The Sura (3:32)

- Presence of Mohammad (2:11)

- Entry to Mecca (3:14)

- The Declaration (2:39)

- The First Martyrs (2:26)

- Fight (4:11)

- The Spread of Islam (3:35)

- Broken Idols (3:40)

- The Faith of Islam (2:33)

The film's release in India in 2007/8 was accompanied by a different soundtrack by multiple artists, featuring unique tracks dedicated to the prophet notably "Marhaba Mustapha" by Indian music composer A. R. Rahman.[36][37] Rahman went onto direct the soundtrack of another film on the prophet, Majid Majidi's Muhammad: The Messenger of God (2015).[38]

| No. | Title | Lyrics | Music | Singer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Marhaba Mustapha" | A. R. Rahman | A. R. Rahman | 5:36 | |

| 2. | "Ya Rasoole Khuda" | Abid Imtiyaz | Liyakat Ajmeri | Mohammed Salamat | 7:38 |

| 3. | "Kaun Hain Aap" | Syed Ahmed | Raj Verma | Mohammed Salamat | 3:15 |

| 4. | "Habib Ullah" | Syed Ahmed | Raj Verma | Mohammed Salamat | 3:34 |

| 5. | "Keh Rahi Hai Meri Saans" | Syed Ahmed | Raj Verma | Mohammed Salamat | 3:50 |

| 6. | "Nabiyun Ke Nabi" | Syed Ahmed | Raj Verma | Mohammed Salamat | 2:33 |

| 7. | "Story of Islam and Teachings of Prophet" (As It Appears in 'Al Risalah') | Raj Verma | 18:02 | ||

| Total length: | 44 minutes | ||||

In popular culture

[edit]The troubled production of The Message inspired American writer Richard Grenier's 1983 comic novel The Marrakesh One-Two.[39]

Potential remake

[edit]In October 2008, producer Oscar Zoghbi revealed plans to "revamp the 1976 movie and give it a modern twist", according to IMDb and the World Entertainment News Network.[40][41][42][43] He hoped to shoot the remake, tentatively titled The Messenger of Peace, in the cities of Mecca and Medina in Saudi Arabia.

In February 2009, Barrie M. Osborne, producer of The Matrix and The Lord of the Rings film trilogies, was attached to produce a new film about Muhammad. The film was to be financed by a Qatari media company and was to be supervised by Sheikh Yusuf al-Qaradawi.[44]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "'Mohammad' Preems In London, July 29". Variety: 5. 7 July 1976.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Coeli; Walker, Adam Hani, eds. (2014). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, LLC. p. 98. ISBN 9781610691789.

- ^ "THE MESSAGE [ARABIC VERSION] (A)". British Board of Film Classification. 20 August 1976. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Gzt (12 July 2021). ""Çağrı filmi nasıl çekildi?" Mustafa Akkad anlatıyor". Gzt (in Turkish). Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ "Illuminating Islam". The Record. 20 March 1977. p. 40. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d "Arab Oil Dollars Pay For Anthony Quinn Epic". The Kansas City Star. 26 January 1975. p. 114. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c "40 Years On, A Controversial Film On Islam's Origins Is Now A Classic". NPR. 7 August 2016. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022.

- ^ "DPLs See 'Mohammad' Moslem Audience Loves It". New York Daily News. 14 March 1977. p. 59. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Peckinpah Disciple Makes 'Mohammad'". The Cincinnati Enquirer. 20 July 1976. p. 6. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Moustapha Akkad, 75, Who Produced Religious and Horror Films, Is Dead". The New York Times. 12 November 2005. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Gambian actor stars in 'Mohammad' movie". St. Joseph News-Press. 20 March 1977. p. 32. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "$20 million epic has its troubles". Berkeley Gazette. 16 April 1975. p. 12. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Turbulent era Quinn plays hunter". News-Pilot. 2 January 1975. p. 21. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Muhammad film title changed after threats." The Times (London, 27 July 1976), 4.

- ^ "Prophet and loss". The Guardian. 29 July 1976. p. 10. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Release slated". The Columbian. 13 February 1977. p. 94. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Brockopp, Jonathan E (19 April 2010). The Cambridge Companion to Muhammad. Cambridge University Press. p. 287.

- ^ a b c Deming, Mark. "Mohammad: Messenger of God". New York Times. Archived from the original on 21 May 2008. Retrieved 8 August 2016.

- ^ "Gunmen stop film on Mohammad". Akron Beacon Journal. 10 March 1977. p. 15. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Moslem Movie". The York Dispatch. 12 March 1977. p. 1. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Producer willing to show controversial film to gunmen". Wichita Falls Times. 10 March 1977. p. 8. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Anuj Saxena's Maverick Productions to distribute movie Al-Risalah". India Forums. 13 December 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ Jafri, Syed Amin (23 February 2008). "Hyderabad: Screening of Islamic fim stopped". rediff.com. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia's First Arabic Release Is Controversial Islamic Epic 'The Message'". Variety. 11 June 2018. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022.

- ^ Medved & Medved 1984, p. 151.

- ^ Dilys Powell, "In pursuit of the Prophet", Sunday Times (London, 1 August 1976), p. 29.

- ^ "The Message". Variety: 22. 18 August 1976.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (March 8, 1977). "Islam as It Lives and Bleeds". Los Angeles Times. Part IV, p. 1.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (March 29, 1977). "Protests aside, 'Mohammad' is a faithful, big-budget epic". Chicago Tribune. Section 2, p. 10.

- ^ a b "Reactions Mixed to Mohammad Film". The Kansas City Star. 30 July 1976. p. 2. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Critic Calls 'Mohammed' Reverent Reward Epic Of Birth Of Islam". Lexington Herald-Leader. 30 July 1976. p. 23. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Eder, Richard (10 March 1977). "Screen: 3-Hour 'Mohammad'". The New York Times: 28.

- ^ Pym, John (September 1976). "Al-Risalah (The Message [Mohammad Messenger of God])". The Monthly Film Bulletin. 43 (512): 187.

- ^ Samir Twair and Pat Twair, "Syrian stars receive first Al-Ataa awards", The Middle East (1 December 1999).

- ^ "1977 Oscars - 50th Annual Academy Awards Oscar Winners and Nominees". Popculturemadness.com. 3 April 1978. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Al Risalah (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) by A.R. Rahman, Liyakat Ajmeri, Raj Verma & Traditional, 21 October 2009, retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "AR Rahman composes music for Al-Risalah". IndiaFM. 16 December 2007. Archived from the original on 16 December 2007. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ "Why a Ban on Majidi's Film on Prophet Muhammad Must Be Challenged". The Wire India. Retrieved 12 August 2023.

- ^ O'Brien, Daniel, Muslim Heroes on Screen, p.192, n.29, Palgrave MacMillan, 2021.

- ^ "The Message Gets A Modern Remake". IMDb.

- ^ Irvine, Chris (28 October 2008). "Prophet Mohammed film The Message set for remake". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 1 November 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (27 October 2008). "Controversial biopic of Muhammad set for remake". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "Prophet Muhammad film announced". BBC News. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ "'Matrix' And 'Lord of the Rings' Producer To Make Movie About The Founder Of Islam". Moviesblog.mtv.com. Archived from the original on 27 December 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

Works cited

[edit]- Medved, Harry; Medved, Michael (1984). The Hollywood Hall of Shame: The Most Expensive Flops in Movie History. Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0207149291.

External links

[edit]- 1976 films

- 1970s biographical drama films

- 1970s adventure drama films

- 1970s historical adventure films

- 1970s war drama films

- Adventure films based on actual events

- 1970s Arabic-language films

- British biographical drama films

- British epic films

- British historical adventure films

- British war drama films

- Drama films based on actual events

- 1970s English-language films

- Epic films based on actual events

- Films scored by Maurice Jarre

- Films about Muhammad

- Films about Islam

- Films directed by Moustapha Akkad

- Films set in the Arabian Peninsula

- Films set in the 7th century

- Films set in deserts

- Films shot from the first-person perspective

- Films shot in Libya

- Films shot in Morocco

- Islam-related mass media and entertainment controversies

- Kuwaiti drama films

- Lebanese drama films

- Libyan drama films

- Moroccan drama films

- Religious adventure films

- Religious epic films

- War epic films

- War films based on actual events

- Historical epic films

- 1976 multilingual films

- British multilingual films

- 1976 directorial debut films

- 1976 drama films

- 1970s in Islam

- English-language Kuwaiti films

- English-language Lebanese films

- English-language Libyan films

- English-language Moroccan films

- 1970s British films

- Religious controversies in India

- Religious controversies in film

- English-language biographical drama films

- English-language war drama films

- English-language historical adventure films

- English-language adventure drama films