Millard Sheets

Millard Sheets | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Millard Owen Sheets June 24, 1907 Pomona, California, U.S. |

| Died | March 31, 1989 (aged 81) Anchor Bay, California, U.S. |

| Education | Chouinard Art Institute |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture, mosaics |

| Movement | California Scene Painting |

| Children | 4 |

| Website | millardsheets |

Millard Owen Sheets (June 24, 1907 – March 31, 1989) was an American artist, teacher, and architectural designer. He was one of the earliest of the California Scene Painting artists and helped define the art movement. Many of his large-scale building-mounted mosaics from the mid-20th century are still extant in Southern California.[1] His paintings are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum in New York, the Chicago Art Institute, the National Gallery in Washington D.C.; and the Los Angeles County Museum.

Early life and education

[edit]Millard Sheets was born June 24, 1907, and grew up in the Pomona Valley, east of Los Angeles.[2][3] He is the son of John Sheets.[4] He attended the Chouinard Art Institute and studied with painters Frank Tolles Chamberlin and Clarence Hinkle.[5] While he was still a teenager, his watercolors were accepted for exhibition in the annual California Water Color Society show. By the age of 19, he was elected into membership of the California Water Color Society.[6] The following year he was hired to teach watercolor painting before his graduation from Chouinard.[7]

Career

[edit]

In May 1927, Sheets exhibited twelve of his landscapes and seascapes oil paintings at the Ebell Club in Pomona.[8] In 1929 he won second prize in the Texas Wildflowers Competitive Exhibitions, and the generous award[9] allowed Sheets to travel to Europe for a year to further his art education.[10] By the early 1930s he began to achieve national recognition as a prominent American artist. He was exhibiting in Paris, New York City, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Houston, St. Louis, San Antonio, San Francisco, Washington D.C., Baltimore, and many other cities throughout the United States. In Los Angeles he was recognized as the leading figure and driving force behind the California Style watercolor movement.

Between 1935 and 1941, his recognition, awards, and output increased, winning him repeated mention in Art Digest and a color reproduction of his work in the book Eyes on America. In 1935 at age 28, he was the subject of a monograph published in Los Angeles. In 1943, he painted four murals at the Main Interior Building in Washington, D.C. in the subject of “The Negro’s Contribution in the Social and Cultural Development of America.”[11]

His art sales enabled him to travel again to Europe, Central America, and Hawaii, where he painted on location. Although his watercolor techniques during this period ranged from very tight to very loose, a consistent, he nevertheless exhibited a personal style.

During World War II, he was an artist-correspondent for Life and the United States Army Air Forces in India and Burma. Many of his works from this period document the scenes of famine, war, and death that he witnessed. His wartime experience also informed his post-war art for a number of years, where while painting in California and Mexico in the 1940s his work followed dark hues and depressing subjects. After the 1950s his style shifted toward brighter colors and subjects from his worldwide travels.

Watercolor and oil painting were only part of Sheets's art career. Through his teaching at Chouinard Art Institute, Otis Art Institute, Scripps College and other institutions, hundreds of artists learned how to paint, and were then guided into art careers. He directed the art exhibition at the Los Angeles County Fair for many years and brought world-class work to Southern California. During the Great Depression, he joined forces with Edward Bruce to hire artists for the Public Works of Art Project, the first New Deal art project. In 1946, he served as a president of the California Water Color Society. In later years, he worked as an architect, illustrator, muralist, printmaker, and art exhibition juror.

Outside of California, he took on commissions for the Detroit Public Library,[12] the Mayo Clinic, the dome of the National Shrine, the University of Notre Dame library, the Hilton Hotel in Honolulu, and the Mercantile National Bank in Dallas.

In 1953, Sheets was appointed director of Otis Art Institute (later named Otis College of Art and Design).[13] Under his leadership, the school's academic program was restructured to offer BFA and MFA degrees, and a ceramics department was created, headed by Peter Voulkos.[14] During that time, a ceramics building, gallery, library, and studio wing were completed. By the time Sheets left Otis in 1962, the form and direction of the college had changed dramatically.[15]

Millard Sheets Art Center

[edit]The Millard Sheets Art Center first began as the Fine Arts Program of the Los Angeles County Fair in 1922. The 20,000+ square-foot art center was built in 1937 by the Works Progress Administration to house the program, the first major gallery dedicated solely to art in Los Angeles County. Each year, the gallery provided visitors to the Los Angeles County Fair with access to art work found throughout the world. In 1994 the building was dedicated to Millard Sheets, and in 2013 was identified by Fairplex as the home for year-round art education and exhibitions and is currently a part of The Learning Centers at Fairplex.[citation needed]

Work

[edit]

Mosaic murals at Home Savings Bank branches

[edit]In the late 1950s, Sheets was commissioned by Howard F. Ahmanson to design Home Savings Bank branches throughout Southern California that would serve as community landmarks by expressing "community values" or presenting "a celebratory version of the community history." To accomplish this goal, Sheets designed his branch buildings with exterior façades containing large mosaic works depicting local heritage.[1][16]

The Ahmanson commissions multiplied to include more than 80 branch buildings after the initial 1955 commission.[17] Sheets resigned his teaching position at Scripps College and established the Sheets Studio in Claremont, California, employing a series of artists.[1]

Sheets produced these untitled mosaics as commercial commissions that are considered official public art,[18] and in the absence of a formal Sheets Studio title they are titled by their images or theme.[12][19] Although they enjoy some protections under the California Arts Preservation Act, many have been destroyed.[1]

List of Home Savings branches with Millard Sheets Studios artwork

[edit]According to researcher Adam Arenson, there were 168 Home Savings of America locations with some kind of Millard Sheets design contribution (including signage).[12][20] However over time many of the mosaic murals have been removed from the facade of the buildings; some of which have been relocated to museums.[21]

Mosaic murals, bronze sculptures, and stained glass designed by the Sheets Studio were placed at scores of bank branches throughout California. The art's highly localized themes made them community landmarks for many neighborhoods and cities.

- 9245 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills,[12][22]

- 6311 Manchester Blvd., Buena Park,[12]

- 8010 Beach Blvd., Buena Park,[12]

- Sunset and Vine, Hollywood,[12]

- 660 S. Figueroa Street, Los Angeles[21]

- 4 West Redlands Blvd., Redlands[23]

- 27319 Hawthorne Blvd., Rolling Hills Estates[22]

- Corner of Arden Way & Expo Blvd, Sacramento[24]

- Mission Beach and Pacific Beach, San Diego; "The Harbor" and "Children's Zoo" plus 6 historical character mosaics, wall painting inside[25]

- 2750 Van Ness, Lombard Street and Van Ness, San Francisco,[12]

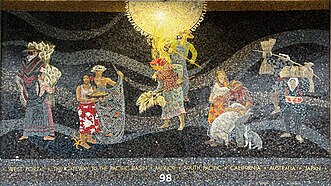

- 98 West Portal Avenue, San Francisco[26]

- 2600 Wilshire Blvd., Santa Monica[22]

- 12051 Ventura Blvd., Studio City[12][22]

- 6570 Magnolia Avenue, Riverside[27]

- Examples of Millard Sheets Studios work

-

La Mesa, San Diego mosaic mural

-

"Early Pomona Family" (1962) mosaic mural in Pomona

-

"Children's Zoo" mosaic mural in San Diego

-

"The Harbor" mosaic mural in San Diego

-

mosaic mural (1977) in West Portal, San Francisco

-

"Scenes of the Old West" (1979) mosaic mural in Buena Park

Other notable work

[edit]- (1934) Southern California landscape, dining room wall painting for homeowners Fred H. and Bessie Ranke in the Hollywood Hills, moved in 2014 to the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California.[28]

- (1934) Tenement Flats A painting in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum done during the Depression for the Public Works of Art Project and chosen to hang in the White House to show President Roosevelt's commitment to the arts and the American people.

- (1939) Early California Three relief panels, stainless steel and enamel, installed at Mark Keppel High School, Alhambra, California

- (1948) The Negro's Contribution in the Social and Cultural Development of America – murals on first floor of the Main Interior Building at U.S. Department of the Interior Building, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C St. NW, Washington, DC[12][29]

- (1956) Panorama of the Pomona Valley, 77 foot long painted mural, Pomona First Federal Bank, Pomona, California[30][31]

- (1961) Scottish Rite Masonic Temple on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles, designed and completed in 1961. For decades the building was considered "one of Los Angeles's most notorious real estate white elephants."[32] Though largely vacant since 1994, it was used as a location for the 2004 adventure film National Treasure starring Nicolas Cage, concerning a fictional long-running Masonic conspiracy.[33] It was refurbished in 2016 to house the Marciano Art Foundation museum.

- (1961) Murals (one 24 ft., one 36 ft.) for the Palomare Room restaurant in Buffums department store, Pomona Mall in Sheets' native Pomona, portraying early Spanish settlement of the Pomona Valley. Sheets also designed the pedestrian mall itself.[34][35]

- (1963) Three Scenes From Shakespeare – A building-mounted mosaic of three vignettes from Antony and Cleopatra, Romeo and Juliet, and Macbeth, Garrison Theater, Scripps College, Claremont, California.[31]

- (1964) Word of Life mural – A large mural on the side of the Hesburgh Library at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. Commonly known among football fans as Touchdown Jesus because of its depiction of Jesus with upraised arms, similar to the official's signal for a touchdown.[12]

- (1966) Loyola Marymount Tapestry, Foley Communication Arts Center, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, California[36][12]

- (1968) Rainbow Murals at Hilton Hawaiian Village[37]

- (1971) The Family of Man, mural at James K. Hahn City Hall East, Los Angeles Mall, Civic Center, Los Angeles, California[38]

- (1974) Horse Haven[39]

- (1975) Drinkers of the Wind[39]

- (1976) Rosemary[39]

- (1977) Two Young Girs and Roosters, Mo'orea, French Polynesia[39]

- (1977) 20 x 30 foot painted mural, San Jose International Airport, San Jose, California; originally in terminal C, moved in 2010 to terminal B.[12][40][41][42]

- (1978) Sunday Morning, Mo'orea[39]

- (1979) Fields and Windmills - Portugal, Watercolor, 21 x 29 inches, signed lower right

- (1979) Afternoon Washing - Lake Chapalam, Mexico, Watercolor, 21 x 29 inches, signed lower left[43]

- (1980) Elegant Ancient Cypress, Watercolor, 22 x 30 inches, signed lower right[44][better source needed]

- (1980) The Pines of Monterey - Deer with Sun and Shadow, Watercolor, 22 x 30 inches, signed lower right

- (1983) Lake Chapala, Mexico, watercolor, 22 x 30 inches, signed lower right[45][better source needed]

- (1987) Tribute to our Heritage, mural, Lubbock Memorial Civic Center[12][3]

-

Rainbow Tower at Hilton Hawaiian Village, twin murals

-

Tenement Flats at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

-

Imperial Bank horse sculpture (1975), Los Angeles

-

Education at Main Interior Building, photographed by HABS

Death

[edit]Sheets died on March 31, 1989, at his home in Anchor Bay in Mendocino County, California, after a long illness. A service was held at his home and at the First Unitarian Church of San Diego.[46]

Sheets had four children. His youngest son, Tony Sheets, has worked in restoring his father's murals, including the mural in San Jose, California.[41][21]

The Paul Bockhorst documentary film, “Design for Modern Living: Millard Sheets and the Claremont Art Community 1935–1975” (2015) was released posthumous.[25]

Awards

[edit]The following are awards Sheets won, among others:[39][unreliable source?]

- Watson F. Blair Purchase Prize, Chicago Art Institute (1938)

- Philadelphia Watercolor Club Prize (1939)

- Dana Watercolor Medal, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (1943)

- Drawing Prize, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1946)

- Gold Brush Award, Artists Guild of Chicago, Award of the Year (1951)

- Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana (1964)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Arenson, Adam (2018). Banking on Beauty: Millard Sheets and Midcentury Commercial Architecture in California. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. pp. 2, 131. ISBN 978-1-4773-1529-3.

- ^ "Artists: Millard Sheets". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ a b Kendall, John (April 2, 1989). "Millard Owen Sheets, 81; Artist, Designer and Teacher". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Millard Sheets papers, circa 1907-2000". Smithsonian Archives of American Art. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Blake, Janet (2012). ""In Love with Painting": The Life and Art of Clarence Hinkle". www.tfaoi.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Women's Club News". Los Angeles Evening Express. Los Angeles, California. April 4, 1930. p. 15. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Outing Spots In South Listed in Stage Line Book". Pomona, California: The Pomona Progress Bulletin. June 14, 1929. p. 21. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Pomona Boy Exhibits 12 Paintings At Ebell Club". The Pomona Progress Bulletin. Pomona, California. May 5, 1927. p. 15. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Wildflower Competitive Exhibitions" Archived 2013-06-20 at the Wayback Machine. San Antonio Art League Museum website. Retrieved Jan. 31, 2016.

- ^ "Wildflower Competitive Exhibitions: Millard Sheets" Archived 2015-12-19 at the Wayback Machine. San Antonio Art League Museum website. Retrieved Jan. 31, 2016.

- ^ Park, Marlene (1984). Democratic vistas : post offices and public art in the New Deal. Gerald E. Markowitz. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 234. ISBN 0-87722-348-3. OCLC 10877506.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Happy Birthday Millard Sheets: Top Ten Public Art Projects to See in Person". KCET. Public Media Group of Southern California. June 24, 2013. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Millard Sheets Named Art Institute Director," Los Angeles Times, August 20, 1953, A1.

- ^ "Art Institute Instruction Plan Mapped". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. June 27, 1954. p. 40. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ "Andres Andersen". Progress-Bulletin. Pomona, California. January 11, 1962. p. 4. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

- ^ Kudler, Adrian Glick (September 10, 2012). "It's Sheets Week, Dedicated to the Man Who Made LA's Mosaicked Mid-Century Banks". Curbed LA. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Back in the Day: Famous mid-century designer's murals can be seen in Riverside, Hemet". Press Enterprise. September 10, 2016. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ "Millard Sheets: (Untitled) Home Savings Bank". Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ Sandefur, Timothy (Spring 2019). "Millard Sheets and the Art of Banking" (PDF). The Objective Standard. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Millard Sheets Studio Public Projects | Adam Arenson". January 29, 2018. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c "The Iconic Murals Of Millard Sheets Are Disappearing From LA". LAist. July 31, 2019. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Kudler, Adrian Glick (September 14, 2012). "Touring 5 Millard Sheets Projects in Greater Los Angeles". Curbed LA. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "What will happen to mural by famed Pomona artist when Redlands Chase branch moves?". Redlands Daily Facts. December 14, 2018. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Wingo, Melanie (August 28, 2024). "Historic recognition rejected: Older Sacramento building won't receive landmark designation". KCRA. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ a b Kahn, Eve M. (June 9, 2016). "The Artist Who Beautified California Banks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Home Savings and Public Art – Public Art and Architecture from Around the World". www.artandarchitecture-sf.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Happy Birthday Millard Sheets: Top Ten Public Art Projects to See in Person". PBS SoCal. June 24, 2013. Retrieved December 5, 2023.

- ^ Karen Wada, Millard Sheets mural moving to the Huntington Archived 2014-11-05 at the Wayback Machine, LA Observed, November 4, 2014

- ^ "Udall Department of the Interior Building: Sheets Murals - Washington DC". Living New Deal. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Millard Sheets and Susan Hertel (Lautmann), "Panorama of the Pomona Valley," 1956". AMOCA. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b Kudler, Adrian Glick (September 12, 2012). "Touring 5 Millard Sheets Projects in Claremont and Pomona". Curbed LA. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ L.A.'s art world eagerly awaits 2017 opening of Marciano muse Archived 2016-12-31 at the Wayback Machine by Deborah Vankin, Los Angeles Times, Dec. 30, 2016.

- ^ Bluejeans moguls to turn Masonic lodge in L.A. into a private museum Archived 2013-07-31 at the Wayback Machine by Roger Vincent, Los Angeles Times, July 24, 2013.

- ^ "Buffums' murals by Millard Sheets return to Pomona". Daily Bulletin. December 7, 2018. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- ^ "Millard Sheets murals commissioned for Buffums Pomona". Progress-Bulletin. October 6, 1961. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved September 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Loyola Marymount Tapestry designed by Millard Sheets, CaliSphere, California Digital Library, June 14, 2019, archived from the original on July 24, 2022, retrieved July 24, 2022

- ^ "Waikiki's Rainbow Landmark". The San Francisco Examiner. San Francisco, California. January 19, 1969. p. 254. Archived from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ "Millard Sheets, Family of Man, City Hall East, Los Angeles". Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Millard Sheets Recent Paintings. New York: Kennedy Galleries, Inc. October 6, 1978. OCLC 4810067. Archived from the original on May 24, 2022. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ "Millard Sheets Mural at San Jose International". Flysanjose.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2021. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ a b "Millard Sheets' son saves artist's doomed mural at San Jose airport". The Mercury News. July 9, 2010. Archived from the original on July 24, 2022. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Millard Sheets historic mural set to be knocked down". Daily News. June 16, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Afternoon Washing", private collection, Lake Chapalam, Mexico, 1979

- ^ "Elegant Ancient Cypress", image from art magazine, 1980

- ^ "Lake Chapala, Mexico, (1983)", www.californiawatercolor.com, 1983, archived from the original on March 3, 2022, retrieved March 3, 2022

- ^ "Obituary: Millard Owen Sheets". Independent Coast Observer. Gualala, California. April 7, 1989. p. 16. Archived from the original on September 20, 2021. Retrieved September 19, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- Millard Sheets at IMDb

- AdamArenson.com “Banking on Beauty” spreadsheet/PDF and map

- Wildflower Competitive Exhibitions

- Millard Sheets: A Legacy of Art and Architecture (complete PDF booklet about his work created for the Getty Pacific Standard Time project by the Los Angeles Conservancy)

- Interview of Millard Sheets, Oral history interview with Millard Sheets, 1986 October-1988 July. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- List of artworks by Millard Sheets at the Smithsonian American Art Museum

- "1934: A New Deal for Artists" (exhibition on the Great Depression featuring Millard Sheets and his contemporaries), Smithsonian American Art Museum

- California Watercolor

- List of artworks by Millard Sheets at the Ruth Chandler Wiliamson Gallery of Scripps College

- 1907 births

- 1989 deaths

- Painters from California

- American watercolorists

- 20th-century American painters

- American male painters

- People from Pomona, California

- Architects from California

- Chouinard Art Institute alumni

- Otis College of Art and Design faculty

- 20th-century American architects

- Scripps College faculty

- American mosaic artists

- World War II artists

- Art in Greater Los Angeles