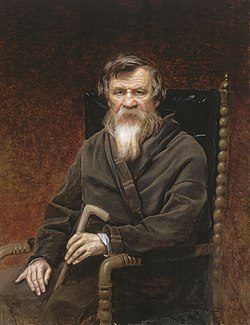

Mikhail Pogodin

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

Mikhail Petrovich Pogodin (Russian: Михаи́л Петро́вич Пого́дин; 23 November [O.S. 11 November] 1800 – 20 December [O.S. 8 December] 1875) was a Russian historian and journalist who, jointly with Nikolay Ustryalov, dominated the national historiography between the death of Nikolay Karamzin in 1826 and the rise of Sergey Solovyov in the 1850s. He is best remembered as a staunch proponent of the Normanist theory of Russian statehood.

Pogodin's father was a serf housekeeper of Count Stroganov, and the latter ensured Mikhail's education at Moscow University. As the story goes, Pogodin the student lived from hand to mouth, because he spent his whole stipend on purchasing new volumes of Karamzin's history of Russia.

Pogodin's early publications were panned by Mikhail Kachenovsky, a Greek who held the university chair in Russian history. Misinterpreting Schlözer's novel teachings, Kachenovsky declared that "ancient Russians lived like mice or birds, they had neither money nor books" and that Primary Chronicle was a crude falsification from the era of Mongol ascendancy. His teachings became exceedingly popular, spawning the so-called sceptical school of imperial historiography.

In 1823, Pogodin completed his dissertation in which he debunked Kachenovsky's idea of the Khazar origin of Rurikid princes. He further stirred up the controversy by proclaiming that serious scholars should not only trust but worship Nestor. The dispute ended with Kachenovsky's chair being devolved on Pogodin. In the 1830s and 1840s he augmented his reputation by publishing many volumes of obscure historical documents and the last part of Mikhail Shcherbatov's history of Russia.

Towards the end of the 1830s, Pogodin turned his attention to journalism, where his career was likewise a slow burner. Between 1827 and 1830 he edited The Herald of Moscow with Alexander Pushkin as one of the regular contributors. Upon first meeting the great poet in 1826, Pogodin remarked in his diary that "his mug doesn't look promising". However, this remark is usually taken out of context as Pogodin wrote glowing reviews of Pushkin's work as early as 1820.

In the wake of the Polish Uprising it fell to Nicholas I's minister of education, Count Uvarov to find ways to unite the various branches of the "true Russians". Uvarov began looking for an author who could provide historical justification for the annexation and integration of the new western provinces into the empire. Uvarov's first choice was Pogodin, who was approached in November 1834 and submitted his work in 1835, however his work did not satisfy the minister's demands nor the tsar's, as his book presented the history of northeastern Rus (Russia) as too distinct and separate from the history of Southern Rus (Ukraine), undermining the project's main goal.[1]

In the report of the investigations into the actives of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius, professors Mikhail Pogodin and Stepan Shevyrev were named as key figures in the Slavophile movement. However, though a key figure in the emerging pan-Slavic movement by stressing the unique and self-awareness of the Russian nation, Pogodin set an example to non-Russian Slavs who wished to celebrate their distinctness and consequently their rights to autonomy and independence.[1]

From its beginning, Ukraine took a special place in the Slavophile movement. Pogodin and Shevyrev both showed a great interest in the culture and history of Ukraine in particular. Podogin saw cultural differences between Russians and Ukrainians that went beyond language and history. He wrote in 1845, "The Great Russians live side by side with the Little Russians, profess one faith, have shared one fate and for, for many years one history. But how many differences there are between the Great Russians and the Little Russians".[1]

In the 1840s, Pogodin suggested that there had been linguistic differences among the population as early as Kievan times, and that they coincide with 19th century's distinctions between Great Russians and Little Russians. Thus, while the population of Kiev, Chernihiv and Halych spoke Little Russian, that of Moscow and Vladimir spoke Great Russian. What more, he considered the Princes of Kiev, including such a major figure in the development of the Grand Duchy of Moscow as Andrei Bogoliubsky, to have been Little Russians. According to Pogodin it was only Bogoliubsky's descendants he argued that had "gone native" in the north-eastern lands and became Great Russians. According to historian Serhii Plokhy "Pogodin's account of Kievan Rus history deprived the early Great Russian narrative of its most prized element—the Kievan period".[1]

Pogodin drastically changed his analysis of Kievan Rus and of Russian nationalism after the arrest of his pro-Ukrainian associate Mykola Kostomarov and the remaining members of the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius. In his 1851 letter to Sreznevsky, Pogodin asserted that in reading the early Kievan Chronicles he detected no trace of the Little Russian language but rather of the Great Russian language, consciously or unconsciously aware of the fact that the chronicles had not been written in Old East Slavic but Church Slavonic.[1]

In 1841 Pogodin joined his old friend Stepan Shevyrev in editing Moskvityanin (The Muscovite), a periodical which came to voice Slavophile opinions. In the course of the following fifteen years of editing, Pogodin and Shevyrev steadily slid towards the most reactionary form of Slavophilism. Their journal became embroiled in a controversy with the Westernizers, led by Alexander Herzen, who deplored Pogodin's "rugged, unbroomed style, his rough manner of jotting down cropped notes and unchewed thoughts".

Pogodin's main focus during the last segment of his scholarly career was on fending off Kostomarov's attacks against the Normanist theory. By that period, he championed the pan-Slavic idea of uniting Western Slavs under the aegis of the tsars and even visited Prague to discuss his plans with Pavel Jozef Šafárik and František Palacký. In the 1870s he was again pitted against a leading historian, this time Dmitry Ilovaisky, who advocated an Iranian origin of the earliest East Slavic rulers.

His grandson Mikhail Ivanovich Pogodin (1884–1969) was a museologist.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Plokhy, Serhii (6 September 2018). Lost Kingdom: A History of Russian Nationalism from Ivan the Great to Vladimir Putin. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-198313-4. OCLC 1090811885.

External links

[edit]- 1800 births

- 1875 deaths

- Writers from Moscow

- People from Moskovsky Uyezd

- 19th-century historians from the Russian Empire

- Slavophiles

- Russian nationalists

- 19th-century journalists from the Russian Empire

- Russian male journalists

- 19th-century male writers from the Russian Empire

- Participants of the Slavic Congress in Prague 1848

- Members of the Russian Academy

- Demidov Prize laureates

- Historians of Kievan Rus'