Middle Passage: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by Owjo911 to version by Mallorca23. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (749194) (Bot) |

Mallorca23 (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

HI Matthew hi who dis Lwm |

|||

HI Matthew hi who dis Lwm{{About|the slave trade route|the novel by [[Charles R. Johnson]]|Middle Passage (novel)|the travelogue by [[V.S. Naipaul]]|The Middle Passage (book)}} |

|||

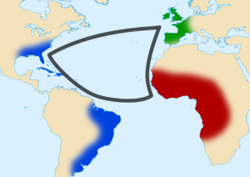

[[Image:Triangular trade.png|thumb|250 px|right|Commercial goods from Europe were shipped to Africa for sale and traded for enslaved Africans. Africans were in turn brought to the regions depicted in blue, in what became known as the "Middle Passage". African slaves were thereafter traded for raw materials, which were returned to Europe to complete the "[[Triangular Trade]]".]] |

[[Image:Triangular trade.png|thumb|250 px|right|Commercial goods from Europe were shipped to Africa for sale and traded for enslaved Africans. Africans were in turn brought to the regions depicted in blue, in what became known as the "Middle Passage". African slaves were thereafter traded for raw materials, which were returned to Europe to complete the "[[Triangular Trade]]".]] |

||

Revision as of 10:28, 25 November 2011

HI Matthew hi who dis Lwm

The Middle Passage was the stage of the triangular trade in which millions of people from Africa[1] were shipped to the New World, as part of the Atlantic slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manufactured goods, which were traded for purchased or kidnapped Africans, who were transported across the Atlantic as slaves; the slaves were then sold or traded for raw materials,[2] which would be transported back to Europe to complete the voyage. A single voyage on the Middle Passage was a large financial undertaking, and they were generally organized by companies or groups of investors rather than individuals.[3]

Traders from the Americas and Caribbean received the enslaved Africans. European powers such as Portugal, England, Spain, France, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, and Brandenburg, as well as traders from Brazil and North America, took part in this trade. The enslaved Africans came mostly from eight regions: Senegambia, Upper Guinea, Windward Coast, Gold Coast, Bight of Benin, Bight of Biafra, West Central Africa and Southeastern Africa.[4]

An estimated 15% of the Africans died at sea, with mortality rates considerably higher in Africa itself in the process of capturing and transporting indigenous peoples to the ships.[5] The total number of African deaths directly attributable to the Middle Passage voyage is estimated at up to two million; a broader look at African deaths directly attributable to the institution of slavery from 1500 to 1900 suggests up to four million African deaths.[6]

For two hundred years, 1440–1640, Portuguese slavers had a near monopoly on the export of slaves from Africa. During the eighteenth century, when the slave trade transported about 6 million Africans, British slavers carried almost 2.5 million.[7]

Journey

The duration of the transatlantic voyage varied widely,[2] from one to six months depending on weather conditions. The journey became more efficient over the centuries; while an average transatlantic journey of the early sixteenth century lasted several months, by the nineteenth century the crossing often required fewer than six weeks.[8]

African kings, warlords and private kidnappers sold captives to Europeans who held several coastal forts. The captives were usually force-marched to these ports along the western coast of Africa, where they were held for sale to the European or American slave traders in the barracoons. Typical slave ships contained several hundred slaves with about thirty crew members. The male captives were normally chained together in pairs to save space; right leg to the next man's left leg — while the women and children may have had somewhat more room. The captives were fed beans, corn, yams, rice, and palm oil. Slaves were fed one meal a day with water, but if food was scarce, slaveholders would get priority over the slaves. Sometimes captives were allowed to move around during the day, but many ships kept the shackles on throughout the arduous journey.

Most contemporary historians estimate that between 9.4 and 12 million Africans arrived in the New World.[9][10] Disease and starvation due to the length of the passage were the main contributors to the death toll with amoebic dysentery and scurvy causing the majority of deaths. Additionally, outbreaks of smallpox, syphilis, measles, and other diseases spread rapidly in the close-quarter compartments. The rate of death increased with the length of the voyage, since the incidence of dysentery and of scurvy increased with longer stints at sea as the quality and amount of food and water diminished. In addition to physical sickness, many slaves became too depressed to eat or function efficiently due to loss of freedom, family, security, and their own humanity.

Slave treatment and resistance

While treatment of slaves on the passage was varied, slaves' treatment was often horrific because the captured African men and women were considered less than human; they were "cargo," or "goods" and treated as such; they were transported for marketing. For example, the Zong, a British slaver, took too many slaves on its voyage to the New World. Overcrowding combined with malnutrition and disease killed several crew members and around 60 slaves. Bad weather made the Zong's voyage slow; the captain decided to drown his slaves at sea, so the owners could collect insurance on the slaves. Over 100 slaves were killed and a number of slaves chose to kill themselves. The Zong incident became fuel for the abolitionist movement and a major court case, as the insurance company refused to compensate for the loss.

While slaves were generally kept fed and supplied with drink, as healthy slaves were more valuable, if resources ran low on the long, unpredictable voyages, the crew received preferential treatment. Slave punishment was very common, as on the voyage the crew had to turn independent people into obedient slaves. Whipping and use of the cat o' nine tails was a common occurrence; sometimes slaves were beaten for “melancholy.” The worst punishments were for rebelling; in one instance a captain punished a failed rebellion by killing one involved slave immediately, and forcing two other slaves to eat his heart and liver.[11]

Slaves resisted in a variety of ways. The two most common types of resistance were refusal to eat and suicide. Suicide was a frequent occurrence, often by refusal of food or medicine or jumping overboard, as well as by a variety of other opportunistic means.[12] Over the centuries, some African peoples, such as the Kru, came to be understood as holding substandard value as slaves, because they developed a reputation for being too proud for slavery, and for attempting suicide immediately upon losing their freedom.[13] Both suicide and self-starving were prevented as much as possible by slaver crews; slaves were often force-fed or tortured until they ate, some still managed to starve themselves to death; slaves were kept away from means of suicide, and the sides of the deck were often netted. Slaves were still successful, especially at jumping overboard. Often when an uprising failed, the mutineers would jump en masse into the sea. Slaves generally believed that if they jumped overboard, they would be returned to their family and friends in their village, or to their ancestors in the afterlife.[14] Suicide by jumping overboard was such a problem that captains had to address it directly in many cases. They used the sharks that followed the ships as a terror weapon. One captain, who had a rash of suicides on his ship, took a woman and lowered her into the water on a rope, and pulled her out as fast as possible. When she came in view, the sharks had already killed her—and bitten off the lower half of her body.[15]

Slave uprisings were fairly common, but few were successful (notably that on the Amistad, which had a key effect on abolition in the US):

When we found ourselves at last taken away, death was more preferable than life, and a plan was concerted amongst us, that we might burn and blow up the ship, and to perish all together in the flames.[16]

The number of participants varied widely, often the uprisings would end with the death of a few slaves and crew, and the surviving rebels were punished or executed to be made examples to the rest of the slaves on board.

Slaves also resisted through certain manifestations of their religions and mythology. They would appeal to their gods for protection and vengeance upon their captors, and would also try to curse and otherwise harm the crew using idols and fetishes. One crew found fetishes in their water supply, placed by slaves who thought it would kill all who drank from it.[14]

Sailors and crew

The sailors experienced subpar conditions and were often employed through coercion. Sailors knew and hated the slave trade, so, at port towns, recruiters and tavern owners would get sailors very drunk (and indebted), and then offer to relieve their debt if they signed contracts with slave ships. If they did not, they would be imprisoned. Sailors in prison had a hard time getting jobs outside of the slave ship industry, since most other maritime industries would not hire “jail-birds,” so they were forced to go to the slave ships anyway.[17]

See also

- Abolitionism

- Atlantic slave trade

- European colonization of the Americas

- History of Africa

- Maafa

- Press gang

- Slave ship

- Triangular trade

References

- Faragher, John Mack. Out of many. Pearson Prentice Hall. 2006: New Jersey.

- Rediker, Marcus. The Slave Ship. Penguin Books. 2007

Notes

- ^ McKissack, Patricia C. and McKissack, Frederick. The Royal Kingdoms of Ghana, Mali, and Songhay. 1995, page 109.

- ^ a b Walker, Theodore. Mothership Connections. 2004, page 10.

- ^ Thomas, Hugh. "The Slave Trade: the story of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1440–1870". 1999, page 293

- ^ Lovejoy, Paul E. Transformations in Slavery. Cambridge University Press, 2000

- ^ Mancke, Elizabeth and Shammas, Carole. The Creation of the British Atlantic World. 2005, page 30-1

- ^ Rosenbaum, Alan S. and Charny, Israel W. Is the Holocaust Unique? 2001, page 98-9

- ^ About.com: The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade

- ^ Eltis, David. The Rise of African Slavery in the Americas. 2000, page 156-7

- ^ Eltis, David and Richardson, David. The Numbers Game. In: Northrup, David: The Atlantic Slave Trade, second edition, Houghton Mifflin Co., 2002.

- ^ p. 95. Basil Davidson. The African Slave Trade.

- ^ Rediker, Marcus. The Slave Ship. 2007, page 16

- ^ Taylor, Eric Robert. If We Must Die. 2006, page 37-8

- ^ Johnston, Harry, and Johnston, Harry Hamilton and Stapf, Otto. Liberia. 1906, page 110

- ^ a b Bly, Antonio T. Crossing the Lake of Fire: Slave Resistance during the Middle Passage, 1720–1842. The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 83, No. 3 (Summer, 1998)

- ^ Rediker, Marcus. The Slave Ship. 2007, page 40

- ^ Taylor, Eric Robert. If We Must Die. 2006, page 39

- ^ Rediker, Marcus. The Slave Ship. Penguin Books. 2007, Page 138-139

Further reading

- Baroja, Pio (2002). Los pilotos de altura. Madrid: Anaya. ISBN 8466716815. rofl friking le