M. John Harrison

M. John Harrison | |

|---|---|

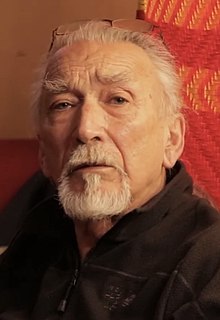

Harrison in 2017 | |

| Born | Michael John Harrison 26 July 1945 Rugby, Warwickshire, England |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | 1966–present |

| Genre | Science fiction, fantasy, horror, literary fiction, autofiction |

| Notable awards | 1989 Boardman Tasker Prize 2002 J. Tiptree Jr. Award 2007 Arthur C. Clarke Award 2007 Philip K. Dick Award 2016 Honorary doctorate, University of Warwick 2020 Goldsmiths Prize |

| Website | |

| ambientehotel | |

Michael John Harrison (born 26 July 1945), known for publication purposes primarily as M. John Harrison, is an English author and literary critic.[1] His work includes the Viriconium sequence of novels and short stories (1971–1984), Climbers (1989), and the Kefahuchi Tract trilogy, which consists of Light (2002), Nova Swing (2006) and Empty Space (2012).

He is widely considered one of the major stylists of modern fantasy and science fiction, and a "genre contrarian".[2] Robert Macfarlane has said: "Harrison is best known as one of the restless fathers of modern SF, but to my mind he is among the most brilliant novelists writing today, with regard to whom the question of genre is an irrelevance."[3] The Times Literary Supplement described him as "a singular stylist" and the Literary Review called him "a witty and truly imaginative writer".[4]

Life and career

[edit]Early years

[edit]Harrison was born in Rugby, Warwickshire, in 1945 to an engineering family.[2] His father died when he was a teenager and he found himself "bored, alienated, resentful and entrapped", playing truant from Dunsmore School (now Ashlawn School).[2] An English teacher introduced him to George Bernard Shaw which resulted in an interest in polemic.[2] He ended school in 1963 at age 18; he worked at various times as a groom (for the Atherstone Hunt), a student teacher (1963–65), and a clerk for the Royal Masonic Charity Institute, London (1966). His hobbies included electric guitars and writing pastiches of H. H. Munro.[5]

His first short story was published in 1966 by Kyril Bonfiglioli at Science Fantasy magazine, on the strength of which he relocated to London. He there met Michael Moorcock, who was editing New Worlds magazine.[2] He began writing reviews and short fiction for New Worlds, and by 1968 he was appointed books editor.[2] Harrison was critical of what he perceived as the complacency of much genre fiction of the time. During 1970, Harrison scripted comic stories illustrated by R.G. Jones for such forums as Cyclops and Finger.[5] An illustration by Jones appears in the first edition of Harrison's The Committed Men (1971).

In an interview with Zone magazine, Harrison said: "I liked anything bizarre, from being about four years old. I started on Dan Dare and worked up to the Absurdists. At 15 you could catch me with a pile of books that contained an Alfred Bester, a Samuel Beckett, a Charles Williams, the two or three available J. G. Ballard's, On the Road by Jack Kerouac, some Keats, some Allen Ginsberg, maybe a Thorne Smith. I've always been pick 'n' mix: now it's a philosophy."[6]

1968–1975: New Worlds, The Committed Men, The Pastel City, and The Centauri Device

[edit]From 1968 to 1975 he was literary editor of the New Wave science fiction magazine New Worlds, regularly contributing criticism. He was important to the New Wave style which also included writers such as Norman Spinrad, Barrington Bayley, Langdon Jones and Thomas M. Disch. As a reviewer for New Worlds he often used the pseudonym "Joyce Churchill" and was critical of many works and writers published using the rubric of science fiction. One of his critical pieces, "By Tennyson Out of Disney" was initially written for Sword and Sorcery Magazine, a publication planned by Kenneth Bulmer but which was never published; the piece was printed in New Worlds 2.

Amongst his works of that period are three stories utilising the Jerry Cornelius character invented by Michael Moorcock. These stories do not appear in any of Harrison's own collections but do appear in the Nature of the Catastrophe and New Nature of the Catastrophe. Other early stories published from 1966 were featured in anthologies such as New Writings in SF, edited by John Carnell, and in magazines such as Transatlantic Review, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, New Worlds, and Quark.

A number of Harrison's short stories of this early period remain uncollected, gathered neither in his first collection The Machine in Shaft Ten, nor in his later collections.

The novel The Committed Men (1971) (dedicated to Michael Moorcock and his wife Hilary Bailey) is an archetypal British New-Wave vision of a crumbling future with obvious debts to the work of Michael Moorcock and J. G. Ballard. It is set in England after the apocalypse. Social organisation has collapsed, and the survivors, riddled with skin cancers, eke out a precarious scavenging existence in the ruins of the Great Society. A few bizarre communities try to maintain their structure in a chromium wilderness linked by crumbling motorways. But their rituals are meaningless clichés mouthed against the devastation. Only the roaming bands of hippie-style "situationalists" (presumably a reference to the then contemporaneous situationist group) have grasped that the old order, with its logic, its pseudo-liberalism and its immutable laws of cause and effect, has now been superseded. Among the mutants are a group of reptilian humans – alien, cancer-free but persecuted by the 'smoothskins'. When one of them is born of a human mother in Tinhouse, a group of humans sets off to deliver it to its own kind – a search of the committed men for the tribes of mutants. David Pringle called the novel "brief, bleak, derivative – but stylishly written."[7]

Harrison's first novel of the Viriconium sequence, The Pastel City was also published in 1971. Harrison would continue adding to this series until 1984. During 1972, the story "Lamia Mutable" appeared in Harlan Ellison's anthology Again, Dangerous Visions; while this tale forms part of the Viriconium sequence, it has been omitted from omnibus editions of the Viriconium tales to date.

During 1974 Harrison's third novel was published, the space opera The Centauri Device (described prior to its publication, by New Worlds magazine, as "a sort of hippie space opera in the baroque tradition of Alfred Bester and Charles Harness). An extract was published in New Worlds in advance of the novel's publication, with the title "The Wolf That Follows". The novel's protagonist, space tramp John Truck, is the last of the Centaurans, victims of a genocide. Rival groups need him to arm the most powerful weapon in the galaxy: the Centauri Device, which will respond only to the genetic code of a true Centauran.

Harrison himself has said of this book:

I never liked that book much but at least it took the piss out of sf’s three main tenets: (1) The reader-identification character always drives the action; (2) The universe is knowable; (3) the universe is anthropocentrically structured & its riches are an appropriate prize for

the colonialistpeople like us. TCD tried to out space opera as a kind of counterfeit pulp which had carefully cleaned itself of Saturday night appetite, vacuuming out all the concerns of real pulp fiction to keep it under the radar of the Mothers of America or whatever they called themselves. Pulp’s lust for life was replaced, if you were lucky, by a jaunty shanty & a comedy brawl. Otherwise, it was lebensraum & a cadetship in the Space Police (these days it’s primarily low-bourgeois freedom motifs & nice friendly sexual release).[8]

Harrison's first short story collection The Machine in Shaft Ten (1975) collects many (but not all) of his early short tales, from such sources as New Worlds Quarterly, New Worlds Monthly, New Writings in SF, Transatlantic Review and others. "The Lamia and Lord Cromis" is an early Viriconium tale. The moody "London Melancholy" features a ruined future London haunted by winged people. None of the stories, with the exception of "Running Down", (a psychological horror tale about a man who is literally a walking disaster area), have been reprinted in his subsequent short story collections. "The Bringer with the Window" features Dr Grishkin, a character also appearing in The Centauri Device, seemingly in Harrison's recurring fictional city of Viriconium.

Harrison's early novels The Committed Men, The Pastel City and The Centauri Device have been reprinted several times. The latter was included in the SF Masterworks series.

1978–1985: Manchester Review, The Ice Monkey, more Viriconium

[edit]Harrison later relocated to Manchester and was a regular contributor to New Manchester Review (1978–79). David Britton and Michael Butterworth of Savoy Books employed him to write in their basement (where he did so "amidst stacks of antique Eagles, Freindz, New Worlds and Styng. A basement that reverberates with indecent exposures of stolen sound, bootlegs sucked from hidden mikes, stacked in neat piles.").[9][10] The commissioned work, originally announced in Savoy publications as By Gas Mask and Fire Hydrant, eventually became the novel In Viriconium.

During the decade of 1976–1986, Harrison lived in the Peak District.[11] In 1983, he published his second short story collection, The Ice Monkey and Other Stories, containing seven tales which capture the pathos, humour, awe, despair, pain and black humour of the human condition. The Ice Monkey was praised by Ramsey Campbell, who stated "M. John Harrison is the finest British writer now writing horror fiction and by far the most original".[12] In "The Incalling", a story of seedy suburban magic which in some ways foreshadows his later novel The Course of the Heart, an editor is haunted by an author's attempts to cure himself of cancer by faith healing.[12] The "Incalling" is one of the few of Harrison's tales (aside from "Running Down") in which a male character is physically ill; though many of his stories feature male characters who are psychologically unwell, in many of his fictions, it is women who are damaged - either physically or emotionally ill or both. "The New Rays" here exemplifies this tendency.

In 1980 Harrison contributed an introduction to Michael Moorcock's early allegorical fantasy, written by Moorcock at age 18, entitled The Golden Barge and published by Savoy Books. That same year he released his second novel in the Viriconium sequence, A Storm of Wings. Set eighty years later than The Pastel City, stylistically it is denser and more elaborate. A race of intelligent insects is invading Earth as human interest in survival wanes. A third novel, entitled In Viriconium (1982) (US title: The Floating Gods), was nominated for the Guardian Fiction Prize during 1982. It is a moody portrait of artistic subcultures in a city beset by a mysterious plague.

The short story "A Young Man's Journey to Viriconium" (1985, later retitled "A Young Man's Journey to London") is set in our world and concerns the idea of escape from it.

1985–1989: Climbers

[edit]Harrison's interest in rock climbing resulted in his semi-autobiographical novel Climbers (1989), the first novel to receive the Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature. Harrison also ghost-wrote the autobiography of one of Britain's best rock climbers, Ron Fawcett (Fawcett on Rock, 1987, as by Mike Harrison).[13] Harrison has repeatedly affirmed in print the importance of rock climbing for his writing as an attempt to grapple with reality and its implications, which he had largely neglected while writing fantasy. The difference in his approach pre- and post-Climbers, can be observed in the extreme stylistic differences between the first novel of the Viriconium sequence The Pastel City and the second, A Storm of Wings. Around the time of writing Climbers, he declared that he had abandoned science fiction forever.[14]

Robert Macfarlane wrote an introduction to the 2013 reissue of Climbers. Writing about the book in The Guardian, he said: "...it is surely the best novel about rock-climbing ever written – though such a description drastically limits its achievement".[3]

1990s: The Course of the Heart, Signs of Life, and Gabriel King novels

[edit]Subsequent novels and short stories, such as The Course of the Heart (1991) and "Empty" (1993), were set between London and the Peak District. They have a lyrical style and a strong sense of place, and take their tension from characteristically conflicting veins of mysticism and realism.

The Course of the Heart deals in part with an experiment in ritual magic gone wrong, and with an imaginary country which may exist at the heart of Europe, as well as Gnostic themes such as the Pleroma. It weaves together mythology, sexuality, and the troubled past and present of Eastern Europe. The origin of the narrative lies in the occasion when three Cambridge students perform a ritualistic act (never shown or fully described) that changes their lives. Years later, none of the participants can remember what exactly occurred; but their vague memories can't rid them of an overwhelming sense of dread. Pam Stuyvesant is an epileptic haunted by strange sensual visions. Her husband Lucas believes that a dwarfish creature is stalking him. Self-styled sorcerer Yaxley becomes obsessed with a terrifyingly transcendent reality. The narrator, the seemingly least affected participant in the ritual (who is haunted by the smell of roses) attempts to help his friends escape the torment that has engulfed their lives. Joel Lane has described The Course of the Heart as "a brilliant use of supernatural themes to explore humanity mortality and loss."[12] The novel incorporates versions of several other Harrison stories including "The Great God Pan", "The Quarry" and "The Incalling".

The novel Signs of Life (1996) is a romantic thriller which explores concerns about genetics and biotechnology amidst the turmoil of what might be termed a three-way love affair between its central characters.

Beginning with The Wild Road in 1996 and concluding with Nonesuch (2001), Harrison coauthored four associated fantasies about cats with Jane Johnson, under the joint pseudonym of "Gabriel King".[15]

Harrison has collaborated on several short stories with Simon Ings, and with Simon Pummel on the short film "Ray Gun Fun" (1998). His work has been classified by some as forming part of the style dubbed the New Weird, along with writers such as China Miéville, though Harrison himself resists being labelled as part of any literary style.

Harrison won the Richard Evans Award in 1999 (named after the near-legendary figure of UK publishing) given to the author who has contributed significantly to the SF genre without concomitant commercial success.

2002–2012: The Kefahuchi Tract trilogy and other works

[edit]Harrison continued to publish short fiction in a wide variety of magazines through the late 1990s and early 21st century. Such tales were published in magazines as diverse as Conjunctions ("Entertaining Angels Unawares", Fall issue 2002), The Independent on Sunday ("Cicisbeo", 2003), The Times Literary Supplement ("Science and the Arts", 1999) and Woman's Journal ("Old Women", 1982). They were collected in his major short story collections Travel Arrangements (2000) and Things That Never Happen (2002).

During 2007 Harrison provided material for performance by Barbara Campbell (1001 Nights Cast, 2007, 2008[16]) and Kate McIntosh (Loose Promise, 2007[17]).

In 2002, Light marked a return to science fiction for Harrison and marked the beginning of the Kefahuchi Tract trilogy. Light was co-winner of the James Tiptree, Jr. Award in 2003. Its sequel, Nova Swing (2006), which contained elements of noir, won the Arthur C. Clarke Award in 2007[18] and the Philip K. Dick Award in 2008.[19] The third novel, Empty Space: A Haunting, was published in August 2012.

2012–present: You Should Come with Me Now, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again and Wish I Were Here

[edit]Harrison published two short stories on Kindle: Cave and Julia (2013) and The 4th Domain (2014).

In 2014, Rhys Williams and Mark Bould organised a conference on Harrison's work at the University of Warwick, UK, called "Irradiating the Object: M. John Harrison". The keynote speakers were Fred Botting (Kingston University) and Sara Wasson (Edinburgh-Napier University).[20] The conference papers, including the keynote address by Tim Etchells, was published as M. John Harrison: Critical Essays edited by Rhys Williams and Mark Bould.[21]

In 2016, he received an honorary D. Litt. from the University of Warwick, UK.[22]

A collection of short stories, You Should Come With Me Now, was published in November 2017.[23]

2020 saw two new books: a novel, The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again[24] and Settling the World: Selected Stories 1970-2020.[25] The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again won the 2020 Goldsmiths Prize,[26] and was longlisted for the 2020 BSFA Award.

In 2023, Harrison released Wish I Was Here, an "anti-memoir".[27]

Reviewing, judging and teaching

[edit]For Harrison's work in New Worlds magazine, see above. The bulk of his reviews were collected in the volume Parietal Games (2005; see below).

Since 1991, Harrison has reviewed fiction and nonfiction for The Guardian, The Daily Telegraph, the Times Literary Supplement and The New York Times.

During 2003 Harrison was on the jury of the Michael Powell Award at the Edinburgh International Film Festival.

He has taught creative writing courses in Devon and Wales, focusing on landscape and autobiography, with Adam Lively and the travel writer Jim Perrin.

In 2009, Harrison shared (with Sarah Hall and Nicholas Royle) the judging of the Manchester Fiction Prize.

Style

[edit]His work has been acclaimed by writers including Angela Carter,[28] Neil Gaiman,[29] Iain Banks (who called him "a Zen master of prose"),[30] China Miéville,[31] William Gibson,[32] Robert Macfarlane[3] and Clive Barker, who has referred to him as "a blazing original".[33] Olivia Laing has said of him: "No one alive can write sentences as he can. He’s the missing evolutionary link between William Burroughs and Virginia Woolf".[34] In a Locus magazine interview, Harrison describes his work as "a deliberate intention to illustrate human values by describing their absence."[35]

Many of Harrison's novels include expansions or reworkings of previously published short stories. For instance, "The Ice Monkey" (title story of the collection) provides the basis for the novel Climbers (1989); the novel The Course of the Heart (1992) is based on his short story "The Great God Pan". The story "Isobel Avens Returns to Stepney in the Spring" is expanded as the novel Signs of Life (1996); the short story "Anima", first published in Interzone magazine, also forms one of the central thematic threads of Signs of Life.

In interviews, Harrison has described himself as an anarchist,[36] and Michael Moorcock wrote in an essay entitled "Starship Stormtroopers" that, "His books are full of anarchists – some of them very bizarre like the anarchist aesthetes of The Centauri Device."[37]

Critical response

[edit]China Miéville has written: "That M. John Harrison is not a Nobel laureate proves the bankruptcy of the literary establishment. Austere, unflinching and desperately moving, he is one of the very great writers alive today. And yes, he writes fantasy and sf, though of a form, scale and brilliance that it shames not only the rest of the field, but most modern fiction."[38]

David Wingrove has written of Harrison: "Making use of forms from sword-and-sorcery, space opera and horror fiction, Harrison pursues an idiosyncratic vision: often grim, but with a strong vein of sardonic humour and sensual detail. Typically, his characters make ill-assorted alliances to engage in manic and often ritualistic quests for obscure objectives. Out of the struggle, unacknowledged motives emerge, often to bring about a frightful conclusion, which, it is suggested, was secretly desired all along. Harrison's vivid, highly finished prose convinces the reader of everything."[39]

Bibliography

[edit]- Fiction

| Year | Title | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1971 | The Committed Men | Science fiction novel set in a post-apocalyptic Britain. London: Hutchinson and New York: Doubleday. Dedicated to Hilary Bailey and Michael Moorcock. The Doubleday edition has textual differences. | |

| The Pastel City | First novel of the Viriconium sequence. London: NEL, 1971 (pbk, first edition); New York: Avon Books, 1971; New York: Doubleday, 1972 (first hc edition). These editions are dedicated to Maurice & Lynette Collier and Linda & John Lutter. Reprint: London: Unwin, 1987 (dedicated to Dave Holmes). | ||

| 1975 | The Centauri Device | Stand-alone space opera. New York: Doubleday, 1974; London: Panther, 1975. The first ed is dedicated to John Price. Reprints: London: Orion/Unwin, 1986 (dedicated to Jon Price); London: Millennium, 2000 (Sf Masterworks series) (no dedication). | |

| The Machine in Shaft Ten and Other Stories | Short story collection. London: Panther, 1975. Dedicated to 'Diane'. Contains: "The Machine in Shaft Ten"; "The Lamia and Lord Cromis"; "The Bait Principle"; "Running Down"; "The Orgasm Band"; "Visions of Monad"; "Events Witnessed from a City"; "London Melancholy"; "Ring of Pain"; "The Causeway'; "The Bringer with the Window"; "Coming from Behind". Note: "Running Down" was later revised for its appearance in The Ice Monkey and Other Stories. | ||

| 1980 | A Storm of Wings | Second novel of the Viriconium sequence. London: Sphere,1980 (dedicated to John Mottershead, Mike Butterworth, Tom Sheridan and Dave Britton) and New York: Doubleday, 1980 (dedicated to Harlan Ellison). British Fantasy Award nominee, 1981[40] Reprint: London: Unwin, 1987 (dedicated to Chris Fowler). | |

| 1982 | In Viriconium | Third novel of the Viriconium sequence. London: Gollancz, 1982 (dedicated to Peter Weatherburn and Joyce Middlemiss). Published in the US as The Floating Gods, New York: Pocket Books, 1983 (dedicated to Fritz Leiber). Nominated for the Guardian Fiction Prize. British Fantasy Award and Philip K. Dick Award nominee, 1983[41] | |

| 1985 | Viriconium Nights | Collection of short stories adding to the Viriconium sequence. New York: Ace (paperback), 1984 (dedicated to Algis Budrys); revised/definitive edition, (1st hardcover ed) London: Gollancz, 1985 (dedication to Budrys removed). The stories in the British hardcover edition are revised and the author's preferred texts. The Ace and Gollancz editions, while they have five stories in common, are effectively different books under the same title. Stories in the Ace ed are: "The Lamia and Lord Cromis", "Lamia Mutable", "Viriconium Knights", "Events Witnessed from a City", "The Luck in the Head", "The Lords of Misrule", "In Viriconium"(an abbreviated version of the 1982 novel of that title), "Strange Great Sins". The Gollancz ed presents its stories in a different running order; it also omits "Lamia Mutable", "Events Witnessed from a City", and "In Viriconium". "The Lords of Misrule" is retitled "Lords of Misrule" in the Gollancz ed. The Gollancz ed contains stories not in the Ace ed, i.e. "The Dancer from the Dance" and "A Young Man's Journey to Viriconium". | |

| The Ice Monkey | Short story collection. London: Gollancz, 1983. Contents reprinted in toto in Things That Never Happen (2002). The version of Running Down included is a version revised from its early appearance in The Machine in Shaft Ten and Other Stories. | ||

| 1989 | Climbers | winner of the Boardman Tasker Prize. Harrison was the first writer to win this award with a work of fiction. Reissued in 2013 with an introduction by Robert Macfarlane. | |

| 1992 | The Course of the Heart | novel. UK: Gollancz, Flamingo. The 2004 Night Shade Books edition (first US edition) adds the short story "The Great God Pan" which Harrison describes in a note as a 'rehearsal' for the novel. The UK ed (Gollancz, 1992) is dedicated "To JJ with love" although this dedication is not reproduced in the 2004 edition. | |

| 1996 | Signs of Life | novel, British SF Award nominee, 1997;[42] British Fantasy Award nominee, 1998[43] | |

| 1997 | The Wild Road | as Gabriel King, written in collaboration with Jane Johnson | |

| 1998 | The Golden Cat | as Gabriel King, written in collaboration with Jane Johnson | |

| 2000 | Travel Arrangements | short story collection. Contents reprinted in toto in Things That Never Happen (2002). | |

| The Knot Garden | as Gabriel King, written in collaboration with Jane Johnson | ||

| 2001 | Nonesuch | as Gabriel King, written in collaboration with Jane Johnson | |

| 2002 | Light | working title The Kefahuchi Discontinuity (as witness the entry on Harrison in David Pringle, ed. The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Fantasy. London: Carlton Books, 1998, 2002, 2006, p. 175) | co-winner of the 2002 James Tiptree, Jr. Award; British SF Award nominee, 2002;[44] Arthur C. Clarke Award nominee, 2003[45]

Winner, Tähtivaeltaja Award, 2005 |

| Things That Never Happen | Omnibus edition of The Ice Monkey and Travel Arrangements, plus some previously uncollected material; the author's choice of his best stories, arranged in chronological order of composition. Intro by China Miéville. Only around 600 copies of the trade ed were produced. The limited edition version (150 copies) is signed by both authors and has laid in a separate booklet, The Rio Brain (a collaboration between Harrison and Simon Ings). | ||

| 2005 | Anima | omnibus edition of the novels Signs of Life and The Course of the Heart. Its title gives a clue to the Jungian themes in Harrison's work. | |

| 2006 | Nova Swing | Gollancz 2006; limited edition Easton Press; sequel to Light, Arthur C. Clarke and Philip K. Dick Awards winner, 2007;[46] BSFA nominee, 2006;[47] British Fantasy and John W. Campbell Awards nominee, 2007.[46] | |

| 2012 | Empty Space | novel; third in the Kefahuchi Tract sequence begun with Light and Nova Swing | |

| 2017 | You Should Come With Me Now: Stories of Ghosts | short story collection; Comma Press, 2017. | |

| 2020 | The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again | novel; Gollancz, June 2020. | |

| 2020 | Settling the World: Selected Stories 1970-2020 | short story collection; Comma Press, August 2020 |

- Graphic novels

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | The Luck in the Head | A Viriconium story adapted in collaboration with illustrator Ian Miller, based on the short story of the same name |

| 2000 | Viriconium | German language adaptation of In Viriconium, illustrated by Dieter Jüdt |

- Nonfiction

| Year | Title | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Fawcett on Rock | as "Mike Harrison", a ghostwritten autobiography of a legendary British rock climber |

| 2005 | Parietal Games | edited by Mark Bould and Michelle Reid, compiles Harrison's reviews and essays from 1968 to 2004 as well as eight essays on Harrison's fiction by other authors |

| 2023 | Wish I Was Here | an 'anti-memoir' |

References

[edit]- ^ Kelley, George. "Harrison, M(ichael) John" in Jay P. Pederson (.ed) St. James guide to science fiction writers. New York: St. James Press., 1996. ISBN 9781558621794 (pp. 422-3).

- ^ a b c d e f Richard Lea (20 July 2012). "M John Harrison: a life in writing". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ a b c Macfarlane, Robert (20 July 2012). "Robert Macfarlane: rereading Climbers by M. John Harrison". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ^ Quoted in 'M. John Harrison News, Interzone 13 (Autumn 1985).

- ^ a b Jacket blurb, M. John Harrison, The Committed Men. London: New Authors Limited, 1971

- ^ "Disillusioned by the Actual: An Interview with M. John Harrison" by Patrick Hudson

- ^ David Pringle. The Ultimate Guide to Science Fiction. Grafton, 1990, p. 67

- ^ Harrison, M. John (2 April 2012). "the centauri device". The M John Harrison Blog. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Savoy Dreams, p. 14

- ^ Andrew Darlington, "Doin' That Savoy Shuffle", International Times; online at [1]

- ^ "M. John Harrison: Profile, Works, Critical Essays, and a List of Books by Author M. John Harrison". www.paperbackswap.com. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b c Lane, Joel. "Harrison, M(ichael) John", in David Pringle, (ed.) St. James Guide to Horror, Ghost, and Gothic Writers. Detroit: St. James Press/Gale, 1998, ISBN 1558622063 (pp. 252-4)

- ^ Fawcett, Ron; Beatty, John; Harrison, Mike (1987). Fawcett on Rock. Unwin Hyman. ISBN 9780044400769.

- ^ M. John Harrison News, Interzone 13 (Autumn 1985).

- ^ "Library of Congress LCCN Permalink n97106123".

- ^ Campbell, Barbara. "1001 Nights Cast". 1001 Nights Cast. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ "Loose Promise". Spin. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ [2] guardian.co.uk article

- ^ [3] Ansible newsletter

- ^ "Conferences". The University of Warwick. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Contemporary Writers: Critical Essays. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Honorary Graduand Biographies - Winter 2016". The University of Warwick. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ "You Should Come With Me Now-CommaPress". Comma Press. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ^ Laing, Olivia (19 June 2020). "The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again by M John Harrison review – brilliantly unsettling". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Settling the World: Selected Stories 1970-2020-CommaPress". Comma Press. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "Goldsmiths Prize won by Harrison for 'literary masterpiece' | The Bookseller". www.thebookseller.com. Retrieved 11 November 2020.

- ^ "WISH I WAS HERE". Serpent's Tail. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ "M. John Harrison's 'You Should Come with Me Now'".

- ^ John Harrison, M. (23 November 2017). You Should Come with Me Now: Stories of Ghosts. Comma Press. ISBN 9781910974346.

- ^ John Harrison, M. (30 December 2010). The Centauri Device. Orion. ISBN 9780575088054.

- ^ "A lot of literary fiction has become its own cliché and it's become very mannered. Of course there's a lot of appallingly bad pulp fiction but when this stuff finds something new and locates itself as part of the tradition it's as good as anything. There are some writers in that tradition in terms of their use of language who as prose stylists are the equal of anyone alive. I'm thinking of people like John Crowley, M John Harrison, Gene Wolfe." Marshall, Richard. "The Road to Perdido: An Interview with China Mieville". 3:AM Magazine. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- ^ John Harrison, M. (15 April 2021). The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again. Orion Publishing Group, Limited. ISBN 9780575096363.

- ^ "M. John Harrison Books | Page 1 | World of Books". www.wob.com. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "The Sunken Land Begins to Rise Again by M John Harrison review – brilliantly unsettling". The Guardian. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ ""Вирикониум" от М. Джон Харисън - Стивън Кинг : Тъмната кула". www.forum.king-bg.info. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Spectrum SF interview Archived 27 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Moorcock, Michael (1977). "Starship Stormtroopers". Archived from the original on 24 December 2002. Retrieved 4 March 2006.

- ^ Harrison, M. John (18 December 2007). Viriconium. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780307418692.

- ^ David Wingrove, The Science Fiction Sourcebook. Prentice Hall Press, 1984, p. 162

- ^ "1981 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "1983 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "1997 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "1998 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "2002 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "2003 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ a b "2007 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ "2006 Award Winners & Nominees". Worlds Without End. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- Critical essays

- Leigh Blackmore. "Undoing the Mechanisms: Genre Expectation, Subversion and Anti-Consolation in the Kefahuchi Tract Novels of M. John Harrison." Studies in the Fantastic. 2 (Winter 2008/Spring 2009). (University of Tampa Press). [4]

- Various hands. Parietal Games (2005), edited by Mark Bould and Michelle Reid, compiles Harrison's reviews and essays from 1968 to 2004 as well as eight essays on Harrison's fiction by other authors. Foreword by Elizabeth Hand.

- Mark Bould and Rhys Williams, eds. M. John Harrison: Critical Essays. Gylphi, March 2019. ISBN 9781780240770. [5]

External links

[edit]- the m john harrison blog (since June 2008)

- Uncle Zip's Window (Harrison's blog, December 2006 to April 2008)

- M. John Harrison at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Infinity Plus interview with David Mathew

- Podcast of interview with M John Harrison during the Irradiating the Object conference on Harrison's work at the University of Warwick on 21st of August 2014

- John Coulthart, Covering Viriconium

- M. John Harrison profile from The Guardian

- 1945 births

- English fantasy writers

- English science fiction writers

- English horror writers

- English short story writers

- Science fiction critics

- British speculative fiction critics

- Boardman Tasker Prize winners

- Goldsmiths Prize winners

- People from Rugby, Warwickshire

- Living people

- English male novelists

- British weird fiction writers

- Pulp fiction writers