Hector's beaked whale

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Hector's beaked whale | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

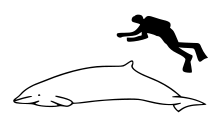

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Ziphiidae |

| Genus: | Mesoplodon |

| Species: | M. hectori

|

| Binomial name | |

| Mesoplodon hectori (Gray, 1871)

| |

| |

| Hector's beaked whale range | |

Hector's beaked whale (Mesoplodon hectori), is a small mesoplodont living in the Southern Hemisphere. This whale is named after Sir James Hector, a founder of the colonial museum in Wellington, New Zealand. The species has rarely been seen in the wild.

Some data supposedly referring to this species, especially juveniles and males, turned out to be based on the misidentified specimens of Perrin's beaked whale - especially since the adult male of Hector's beaked whale was only more recently described.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][excessive citations]

Taxonomy

[edit]The English taxonomist John Edward Gray first named the species Berardius hectori in 1871, based on a specimen (a 2.82 metres (9 ft 3 in) male) collected in Tītahi Bay, New Zealand in January, 1866.[13] The following year, 1872, English anatomist William Henry Flower placed it in the genus Mesoplodon, while in 1873, Scottish scientist James Hector assigned the same specimen to the species M. knoxi. The species remained in the genus Mesoplodon until 1962, when Charles McCann, a vertebrate zoologist at the Dominion Museum in Wellington, argued that the species only represented a juvenile of Berardius arnuxi. Beaked whale specialist Joseph Curtis Moore (1968) and J. G. B. Ross (1970) contested this designation, arguing that M. hectori was a valid species. Adult male specimens from the 1970s and 1980s confirmed the species' specific status.[14]

Molecular Taxonomy

[edit]

With abundant and easily observable species, the use of synapomorphic characters to assign observed individuals to a particular species, is a reasonably effective approach to taxonomy, at least in its rudimentary phase.[15] However, the translation of this approach to rare species with elusive life histories, such as the Hector's beaked whales, can be problematic for many reasons. Also, the usefulness of whole or partial "voucher" specimens in private collections to assign taxonomic difference based on morphology is equally susceptible to inaccuracy, and additionally can lead to unethical acquisition methods, such as illegal hunting of a rare species.[16] Therefore, the accurate and ethical approach to the taxonomic study of rare and elusive species, such as are found within the mysterious, deep-diving family Ziphiidae, is a molecular phylogenetic taxonomic methodology.[17] This method has yielded insightful discovery in recent studies of the family Ziphiidae. Between 1975 and 1997, five beaked whales were found stranded in Southern California; based on morphology, four were identified as members of M. Hectori and one was identified as a member of Ziphius cavirostris.[3] This discovery was puzzling, because although the suspected range of Ziphius cavirostris was met by the stranding location, M. Hectori was thought to be restricted solely to the Southern Hemisphere.[3] mtDNA sequencing of the sample species revealed that all five individuals could be genetically distinguished from all other members of Ziphiidae, including the two species they were previously identified as.[18] They were subsequently classified as a new species, Perrin's beaked whale (M. Perrini).[18] More recent phylogenetic analyses of nuclear actin sequences substantiated the validity of this classification, as a distinct 34 base-pair deletion was found in the allele, screened across all species, of the two M. perrini samples in particular.[17]

Description

[edit]Reaching a maximum length around 4.2 m (1.9 m when born), and with an estimated weight around 1 tonne (1.032 tons), Hector's is one of the smallest of the beaked whales. It is known from only a few stranded animals and a single confirmed sighting of a juvenile off Western Australia.[1] Hector's beaked whales are dark greyish-brown dorsally, paler ventrally. A single female specimen found in Argentina was light grey dorsally and white ventrally.[19] An individual male described in the same study had several scars and teeth marks found diffuse on its back and flanks. Intra-specific male-to-male interactions are possibly the cause for such marks. Additionally, oval white scars on the ventral portion of this male specimen were likely caused from cookie-cutter sharks of the Isistius species. Another single adult male specimen had a white beak and white on the anterior portion of the head, with white, linear scars criss-crossing its body, while the juvenile seen off Western Australia had a mask covering its eyes and extending unto its melon and upper beak. The melon, which is not very prominent, slopes quite steeply to the short beak. The dorsal fin is triangular to slightly hooked, small, and rounded at the tip. The leading edge of the dorsal fin joins the body at a sharp angle.

Stomach

[edit]Like other members of the Mesoplodont genus, the stomach is divided into four chambers.[8] The proximal main stomach, the distal main stomach, the connecting stomachs, and the pyloric stomach are the four chambers respectively.[8][19] The first, second, and fourth chambers are pink in color and soft to touch. The third chamber is grey in color and hard externally. The first and third chamber have internal folds but the folds are longer and larger in the third chamber. The second chamber is smooth, with no folds. The first chamber connects to the esophagus and the fourth chamber connects to the small intestine. The orange gastric fluid found in the stomach has also been found in some areas of the intestines. The specimen's stomach from Argentina had many small crystalline lenses in the first and fourth stomachs. Although, other food remains were not present. The specimen's stomach also had dozens of nematodes in all the stomach chambers except the connecting chamber.[19] Histo-pathological analysis showed that these nematodes were later found to be of the Anisakis species.[20]

Dentition

[edit]Adult males have a pair of flattened, triangular teeth near the tip of the lower jaw. As with most other beaked whales, the teeth do not erupt in females.

In March 2016, the South Australian Museum conducted a necropsy on a beached female specimen of the species from Waitpinga beach, near Adelaide, South Australia. The specimen was found to have a pair of large fangs not seen among the species typical dentition, especially for females, who typically have none. The fangs are possibly vestigial, or atavisms of some other kind, though a definitive answer is difficult because of the dearth of knowledge about the species.[21]

Distribution and ecology

[edit]Hector's beaked whale has a circumpolar distribution in cool temperate Southern Hemisphere waters between about 35 and 55°S.[22] Most records are from New Zealand, but also reports from Falkland Sound, Falkland Islands, Lottering River, South Africa, Adventure Bay, Tasmania, and Tierra del Fuego, in southern South America have been made. Supposed Northeast Pacific records in the older literature actually refer to Perrin's beaked whale.

Sightings are rare due to their deep-ocean distribution, elusive behaviour and possible low numbers. Nothing is known about the diet of this species, although it is assumed to feed on deepwater squid and fish. Because they lack functional teeth, they presumably capture most of their prey by suction.

Body scarring suggests there may be extensive fighting between males, which is common in beaked whales.[23] Nothing is known about breeding in this species.

This species has never been hunted at all, and has not entangled itself in fishing gear. Most records of the whale have been stranded specimens on beaches, particularly in New Zealand.

Conservation

[edit]Hector's beaked whale is covered by the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region (Pacific Cetaceans MOU).[24]

Specimens

[edit]- MNZ MM001834[25] - 16 July 1980; Kaikoura, New Zealand

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Pitman, R.L.; Brownell Jr.; R.L. (2020). "Mesoplodon hectori". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T13248A50366525. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T13248A50366525.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b c Mead, James G. (1981). "First records of Mesoplodon hectori (Ziphiidae) from the Northern Hemisphere and a description of the adult male". Journal of Mammalogy. 62 (2): 430–432. doi:10.2307/1380733. JSTOR 1380733.

- ^ Mead, James G. (1984). "Survey of reproductive data for the beaked whales (Ziphiidae)" (PDF). International Whaling Commission Special Issue. 6: 91–96.

- ^ Mead, James G.; Baker, Alan N. (1987). "Notes on the rare beaked whale, Mesoplodon hectori (Gray)". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 17 (3): 303–312. Bibcode:1987JRSNZ..17..303M. doi:10.1080/03036758.1987.10418163.

- ^ Mead, James G. (1989). "Beaked whales of the genus Mesoplodon". In Ridgway, S.H.; Harrison, R. (eds.). Handbook of marine mammals Vol.4. London: Academic Press. pp. 349–430. doi:10.2307/2403599. JSTOR 2403599.

- ^ Jefferson, T.A.; Leatherwood, S.; Webber, M.A. (1993). FAO species identification guide: Marine mammals of the world (PDF). United States & Rome: United States Environment Programme & Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

- ^ a b c Mead, James G. (1993). "The systematic importance of stomach anatomy in beaked whales" (PDF). IBI Reports. 4: 75–86.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Carwadine, M. (1995). Whales, dolphins and porpoises. London: HarperCollins. ISBN 0004722736.

- ^ Reeves, Randall R.; Leatherwood, S. (1994). Dolphins, porpoises and whales: 1994-98 Action plan for the conservation of cetaceans. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. ISBN 2-8317-0189-9.

- ^ Henshaw, M.D.; Leduc, R.G.; Chivers, S.J.; Dizon, A.E. (1997). "Identification of beaked whales (family Ziphiidae) using mtDNA sequences". Marine Mammal Science. 13 (3): 487–495. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1997.tb00656.x.

- ^ Messenger, S.L.; McQuire, J.A. (1998). "Morphology, molecules and the phylogenetics of cetaceans". Systematic Biology. 47 (1): 90–124. doi:10.1080/106351598261058. PMID 12064244.

- ^ Gray, J.E. (1871). "Notes on the Berardius of New Zealand". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 8 (44): 115–117. doi:10.1080/00222937108696444. ISSN 0374-5481.

- ^ Mead, James G.; Baker, Alan N. (1987). "Notes on the rare beaked whale,Mesoplodon hectori(Gray)". Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 17 (3): 303–312. Bibcode:1987JRSNZ..17..303M. doi:10.1080/03036758.1987.10418163. ISSN 0303-6758.

- ^ Yeates, David (June 2001). "Species Concepts and Phylogenetic Theory: A Debate. Quentin D. Wheeler , Rudolf Meier". The Quarterly Review of Biology. 76 (2): 234–235. doi:10.1086/393912. ISSN 0033-5770.

- ^ Tubbs, Philip K. (1991). "I.u.b.s. Section Of Zoological Nomenclature. Report Of Meeting, Ambsterdam, 6 September 1991". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 48: 293–294. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.757. ISSN 0007-5167.

- ^ a b Dalebout, M. L.; Baker, C. S.; Mead, J. G.; Cockcroft, V. G.; Yamada, T. K. (2004-11-01). "A Comprehensive and Validated Molecular Taxonomy of Beaked Whales, Family Ziphiidae". Journal of Heredity. 95 (6): 459–473. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.507.2896. doi:10.1093/jhered/esh054. ISSN 1465-7333. PMID 15475391.

- ^ a b Dalebout, Merel L.; Mead, James G.; Baker, C. Scott; Baker, Alan N.; Helden, Anton L. (July 2002). "A New Species of Beaked Whale Mesoplodon perrini sp. n. (Cetacea: Ziphiidae) Discovered Through Phylogenetic Analyses of Mitochondrial DNA Sequences". Marine Mammal Science. 18 (3): 577–608. Bibcode:2002MMamS..18..577D. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2002.tb01061.x. ISSN 0824-0469.

- ^ a b c Cappozzo, H. L.; Negri, M. F.; Mahler, B.; Lia, V. V.; Martinez, P.; Gianggiobe, A.; Saubidet, A. (2005). "Biological data on two Hector's beaked whales, Mesoplodon hectori , stranded in Buenos Aires province, Argentina". Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals. 4 (2): 113–128. doi:10.5597/lajam00076. ISSN 2236-1057.

- ^ Nikolov, Pavel N.; Cappozzo, H. Luis; Berón-Vera, Bárbara; Crespo, Enrique A.; Raga, J. Antonio; Fernández, Mercedes (August 2010). "Cestodes from Hector's Beaked Whale (Mesoplodon hectori) and Spectacled Porpoise (Phocoena dioptrica) from Argentinean Waters". Journal of Parasitology. 96 (4): 746–751. doi:10.1645/ge-2200.1. ISSN 0022-3395. PMID 20486735. S2CID 22848752.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (May 19, 2016). "Stranded, Rarely Seen Beaked Whale Has Strange Fang". LiveScience. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

- ^ "Hector's Beaked Whale - The Australian Museum".

- ^ "Hector's beaked whale". Whale & Dolphin Conservation UK. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ http://www.pacificcetaceans.org/ Official webpage of the Memorandum of Understanding for the Conservation of Cetaceans and Their Habitats in the Pacific Islands Region

- ^ http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/objectdetails.aspx?oid=48002

Further reading

[edit]- Baker, Alan N. (1990): Whales and dolphins of New Zealand and Australia: An identification guide. Victoria University Press, Wellington.

- Perrin, William F.; Wursig, Bernd & Thewissen, J.G.M (eds.) (2002): Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- Reeves, Randall R.; Steward, Brent S.; Clapham, Phillip J. & Owell, James A. (2002): Sea Mammals of the World. A & C Black, London. ISBN 0-7136-6334-0