Melvin T. Mason

Melvin T. Mason | |

|---|---|

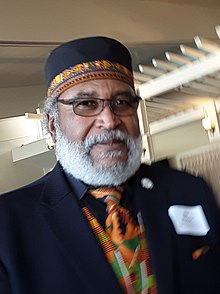

Mason in 2019 | |

| Born | January 7, 1943 Providence, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Civil rights activist, social worker |

| Known for | 1984 presidential candidacy (SWP) |

| Movement | Civil Rights Movement |

| Spouse | Regina Mason |

Melvin T. Mason (born January 7, 1943) is an American politician who ran as Socialist Workers Party candidate for President of the United States in the 1984 United States presidential election.[1][2][3]

Early life

[edit]Melvin T. Mason was born in Providence, Kentucky on January 7, 1943[1][3] and moved to Seaside, California in 1956 with his mother when he was 13.[4] Mason became a star basketball player at Monterey High School.[1][3]

Military service

[edit]Mason graduated from high school in 1960 and then attended Monterey Peninsula College (junior college) until 1961 when he entered the Air Force.[1][3] Mason was named Air Force European Command Player of the Year in 1964, after setting high scoring records for the US military in Europe.[1][5] The Air Force gave Mason a bad conduct discharge in 1965. Mason believes that the bad conduct status was because he had objected to bad treatment of black servicemen. US Senator Thomas Kuchel had the discharged changed to honorable.[5]

High education and collegiate basketball

[edit]1966 Mason returned to Monterey Peninsula College where he became the only All-America basketball player in the school's history.[1][3] He accepted an Oregon State University basketball scholarship but after taking stands against racist treatment of black basketball players, he lost his scholarship in 1966.[5] Mason was banned from playing basketball at any college in the U.S and his sports career was over.[citation needed]

In 1972 Mason earned B.A. in social science at Golden Gate University,[5] and in 1995 an M.A. in social work from San Jose State University.

Political activism

[edit]Mason joined the Black Panther Party in 1968.[6][7][8] and in 1970 he organized the Black United Farmworkers (UFW) support committee.[5] In 1976 Mason was involved investigations and campaigns to stop police brutality on the Monterey Peninsula and Salinas California.[2][4] 1980 Mason was elected[7][2] to the city council of Seaside, CA . Mason had launched campaign to recall former Seaside mayor (then a city councilman) Lou Haddad, whom Mason called an “enemy of black people.” He joined a broad coalition called the Citizens’ League for Progress[9] and defeated Haddad. That next year, Mason ran for the Seaside City Council seat and won.[9]

In 1982 Mason tried to run for Governor of California on the Socialist Workers Party ticket when he was ruled off the ballot.[10] 1984 – Ran as Socialist Workers Party candidate for United States President in the 1984 United States presidential election.[1][2][3] Along with vice presidential candidates Andrea Gonzales and Matilde Zimmermann (different vice presidential candidates in different states), he received 24,672 votes.[10]

Mason was a 1988 plaintiff in a lawsuit against government spying on activists.[11] A federal court decision codified the successful fifteen-year legal effort by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) regarding decades of spying and disruption by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[12]

From 1996 until retirement in 2006, Mason worked at California State University Monterey Bay (CSUMB).[5] He was appointed to the Access to Excellence Committee, designed to increase the admission of minority students with the California State University System.[1][6] 1998 The police shooting of Charles Vaughn[13] led to a new crisis intervention training for Monterey County police forces.[14][15] In 2001 Mason was licensed as a clinical social worker (LCSW) by the California Board of Behavioral Sciences. In 2002 Mason was elected President of the Monterey, California Peninsula chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People for two consecutive terms[5] Mason chaired a committee that successfully created Monterey Peninsula College's trustee districts to ensure voter equity and increase minority representation on the college's board of trustees[16] Mason is the co-founder of The Village Project[17] that provides services culturally tailored to African Americans and other populations historically underserved by mental health systems and after-school academy for high-risk students.[7][17]

Awards and recognition

[edit]- 1998 – Monterey County American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Ralph B. Atkinson Award[18]

- 1999 – KSBW Jefferson Award for Outstanding Volunteer Community Service

- 2002 –Baha'i 23rd Human Rights Award[19]

- 2007 – Stephen E Ross award for community service and advocate for justice: awarded by the NAACP of the Monterey Peninsula[5][17]

- 2007 – Sam Farr, US House of Representatives :resolution in honor of Mel Mason Congressional Record October 22,[5]

- 2011 – California Community College Hall of Fame induction[20][6]

- 2018 – Cal Wellness Sabbatical Program Award[17] designed to improve the long-term effectiveness of nonprofits by investing in the health and wellness of leaders and building staff capacity to manage operations (give them a sabbatical break.)

- 2018 – Monterey Peninsula College President's Award, shared with wife Regina Mason, for community service by MPC Alumni[21]

Books about Mason and his times

[edit]- Mel Mason: The Making of a Revolution (1982) ISBN 0-87348-448-7.[3]

- The trial of Leonard Peltier, Messerschmidt, James W. 1982 South End Press. Boston[22]

- International Trotskyism, 1929–1985: A Documented Analysis of the Movement, Alexander, R. J. (1991). Duke University Press.[10]

- McKibben, Carol (2012). Racial Beachhead: diversity and democracy in a military town. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804778442.[9]

- Reach: 40 black men speak on living, leading and succeeding Ben Jealous Simon & Schuster 2015 pp 143–140[23]

- Voices of Change:the People's Oral History Project : interviews with Monterey County activists and organizers, 1934-2015 (2016) Karnes, Gary. Araujo, Karen. Martinez, Juan[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h "Mason, Melvin T. "Mel". Notable Kentucky African Americans Database. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Karnes, Gary; Araujo, Karen; Martinez, Juan (September 20, 2016). Voices of change : the People's Oral History Project : interviews with Monterey County activists and organizers, 1934-2015 (First U.S. ed.). Pacific Grove, California: Park Place Publications. ISBN 9781943887002. OCLC 957494434.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mason, Melvin T. (1982). Mel Mason: The Making of a Revolutionary. Pathfinder Press. ISBN 0873484487.

- ^ a b Ryce, Walter (January 26, 2012). "As the Monterey county branch of the NAACP enters its 80th year, the activists who helped build Seaside into a center of black power look back on the fight for equality". Monterey County Herald. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Congressional Record of the House of Representatives of the United States : passed on October 22, 2007 introduced by Sam Farr 110th Congress, Congressional Record; 1st Session Issue: Vol. 153, No. 160

- ^ a b c Taylor, Dennis (March 20, 2011). "A lifelong battle for equality". Monterey County Herald. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c Ryce, Walter (May 28, 2015). "Mel Mason had to assert his own humanity, he also asserts the humanity of others". Monterey County Weekly. Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ Self, Robert O., 1968- (2003). American Babylon : race and the struggle for postwar Oakland. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691070261. OCLC 51445643.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c McKibben, Carol Lynn (2012). Racial beachhead : diversity and democracy in a military town : Seaside, California. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804778442. OCLC 762325021.

- ^ a b c Alexander, Robert J. (1991). International Trotskyism, 1929–1985: A Documented Analysis of the Movement. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 72, 873. ISBN 978-0822309758.

- ^ FBI on trial : the victory in the Socialist Workers Party suit against government spying. Jayko, Margaret. (1st ed.). New York: Pathfinder Press. 1988. ISBN 0873485327. OCLC 19684874.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities (Church committee)". United States Senate. April 29, 1976. Archived from the original on October 9, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ^ Worth, Mark (January 13, 2000). "Based on the high-profile killings of minorities in Monterey County and throughout the U.S., it's an ugly question that cries out for an answer". Monterey County Weekly. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ Livernois, Joe (April 4, 2019). "The Cops Shot Chuck". Voices of Monterey Bay.

- ^ "Monterey County's finest learn how to deal compassionately with the mentally ill". Monterey County Weekly. April 27, 2000. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

- ^ "Mel Mason, President, Monterey Peninsula Branch, NAACP, and Co-Founder of the Village Project". Panetta Institute. October 21, 2019. Archived from the original on September 11, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Herrera, James (November 8, 2018). "Mel Mason, executive director of The Village Project in Seaside, to receive Sabbatical Program Award". Monterey Herald. Archived from the original on October 18, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- ^ Marshall, Tera (May 4, 1999). "Outstanding Community Service Recognized". Otter Realm. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ "Human Rights Award". Salinas Californian. December 2, 2002. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- ^ "News & Special Events | Monterey Peninsula College". www.mpc.edu. Archived from the original on November 6, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ Reyes, Juan (April 27, 2018). "MPC alums receive President's Award: Mel and Regina Mason recognized for social justice work in Monterey County". Monterey Herald. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ Messerschmidt, James W (1983). The trial of Leonard Peltier. Boston: South End Press. ISBN 089608163X. OCLC 9926275.

- ^ Jealous, Ben (February 3, 2015). Reach : 40 black men speak on living, leading and succeeding. Jealous, Benjamin Todd, 1973-, Shorters, Trabian. (First Atria paperback ed.). New York. ISBN 9781476799834. OCLC 900194086.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- 1943 births

- Living people

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- African-American candidates for President of the United States

- Candidates in the 1984 United States presidential election

- Golden Gate University alumni

- People from Monterey County, California

- People from Seaside, California

- Socialist Workers Party (United States) politicians from California

- Socialist Workers Party (United States) presidential nominees

- 20th-century African-American politicians

- 21st-century African-American politicians

- Monterey High School (Monterey, California) alumni

- San Jose State University alumni