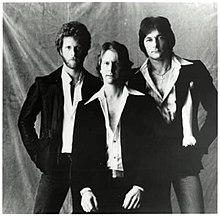

McGuinn, Clark & Hillman

McGuinn, Clark & Hillman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1977–1981 |

| Labels | Capitol |

| Past members | Roger McGuinn Gene Clark Chris Hillman |

McGuinn, Clark & Hillman were an American rock group consisting of Roger McGuinn, Gene Clark, and Chris Hillman, who were all former members of the band the Byrds.[1] The group formed in 1977 and was partly modeled after Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and, to a lesser extent, the Eagles.[1][2] They were reasonably successful commercially in the United States, with their debut album reaching number 39 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tapes chart[3] and the single "Don't You Write Her Off" reaching number 33 on the Billboard Hot 100.[4][5]

Clark left the band in late 1979, due to his increasing drug abuse and deteriorating mental state, and therefore only participated in the recording of two albums with the group.[6][7][8] A third album was released in late 1980 and credited to McGuinn & Hillman alone, after which the duo split up in early 1981.[1][9]

Background

[edit]The Byrds had formed in 1964, with lead guitarist Roger McGuinn, bassist Chris Hillman, and principal songwriter Gene Clark all being founding members. The band pioneered the musical genre of folk rock with their cover of Bob Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man", which became a transatlantic number 1 hit single in 1965.[10][11][12] The song was the first folk rock smash hit and ushered in a period of tremendous commercial success for the band.[13][14] The albums Mr. Tambourine Man and Turn! Turn! Turn! followed, along with the hit singles "All I Really Want to Do" and "Turn! Turn! Turn!" (the latter of which reached the number 1 position in the U.S. charts).[11][12]

In early 1966, Clark left the Byrds due to problems associated with anxiety, his increasing isolation within the band, and his fear of flying, which made it difficult for him to keep up with the band's itinerary.[15] There was also resentment from the other band members that Clark's songwriting income had made him the wealthiest member of the group.[15][16] Following Clark's departure, the Byrds helped to pioneer the musical sub-genres of psychedelic rock[17] and country rock,[18] although their popularity began to wane with mainstream pop audiences.[19] Nevertheless, they were considered by many critics to be forefathers of the late 1960s rock underground.[20]

The Byrds underwent many personnel changes in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with Hillman leaving the band in late 1968 and McGuinn remaining the only constant member of the group.[21][22] The band finally dissolved in mid-1973, following a reunion of the original line-up.[23]

Between 1973 and 1977, McGuinn established his own solo career, releasing a number of solo albums and participating in Dylan's Rolling Thunder Revue.[22] Hillman had been a member of the Flying Burrito Brothers and Manassas after leaving the Byrds the first time; following the 1973 reunion, he became a member of the Souther–Hillman–Furay Band and released the solo albums Slippin' Away (1976) and Clear Sailin' (1977).[24] Clark had embarked on a critically acclaimed but commercially unsuccessful solo career after leaving the Byrds in 1966, and after the 1973 reunion he released the albums No Other (1974) and Two Sides to Every Story (1977), which were again met with enthusiastic reviews, but low sales.[25]

Live performances (1977)

[edit]In March 1977, a twenty-one date European tour was announced in which Clark, Hillman, and McGuinn would perform as solo artists.[26][27] Although speculation in the press was rife from the start about a possible on-stage reunion of the three ex-Byrds, the publicity for the tour made it clear that each artist would be fronting their own bands and not sharing the stage with the others.[27][28] However, in reality, all three musicians had signed a contract with the tour promoter which stated that an on-stage mini-Byrds reunion was required at the close of each show, although this was ignored for all but one of the performances.[28]

The tour, which began in Dublin on April 27, 1977,[26] featured Clark backed by his KC Southern Band, Hillman fronting the Chris Hillman Band, and McGuinn playing with his touring group Thunderbyrd.[29][28] From the beginning the tour was dogged with sound and logistical problems, and a show on April 29 in Birmingham, England had to be cancelled due to the musicians being unable to appear as a result of customs difficulties.[27][28][26] In addition, relations were frosty between the three headline musicians, with the ex-Byrds barely speaking to each other backstage.[28]

On April 30, during the first of two sold-out nights at London's Hammersmith Odeon, the much speculated upon reunion occurred when McGuinn invited Clark and Hillman onto the stage to perform the Byrds' songs "So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star", "I'll Feel a Whole Lot Better", "Mr. Tambourine Man", and "Eight Miles High".[28] The BBC recorded both of the Hammersmith Odeon concerts and broadcast an hour's worth of highlights almost a year later on April 8, 1978, as part of their In Concert program.[26] In 1997, a double CD compilation of tracks from the two nights was released by Strange Fruit Records as 3 Byrds Land in London.[29]

The on-stage reunion failed to take place at the second London show and was also absent from the next two gigs in Manchester and Leeds.[28] The day after the Leeds show, Hillman unexpectedly quit the tour, citing breaches of contract by the tour agency Cream International Artists.[30] Although McGuinn and Clark completed one further concert together in Glasgow, Scotland, the tour was cancelled.[30]

The reaction of the press to the tour was mixed; some UK publications covered the shows with double-page spreads,[28] while other publications were critical of both the quality of the performances and the solo material that the three ex-Byrds chose to perform.[29] The Byrds' biographer Johnny Rogan has remarked on a general sense of ambivalence towards the three musicians in the UK press coverage, due to most critics being more interested in the punk bands that had appeared on the British music scene in 1977.[28]

Becoming a trio (1977–1978)

[edit]"There is definitely a cycle happening. The fact that both of us feel comfortable performing a folkier show at this point and actually doing a concert set involving the audience in singing and participating in the show with us, without electric instruments—not that we have any prejudice against electric instruments—it's just that it's time to do this again, to stand up in front of people and sing and play and entertain people. And they're ready for it now."

Despite the European tour's backstage politics and eventual cancellation, the shows served to rekindle the three musicians' desire to work together again.[32] Upon returning to the United States, arrangements were made for McGuinn and Clark to tour together as an acoustic duo in October 1977.[32][31] The songs that the duo chose to perform on the tour included material from their respective solo careers, a smattering of Dylan covers, and such Byrds hits as "So You Want to Be a Rock 'n' Roll Star", "Chestnut Mare", and "Eight Miles High".[2]

As the McGuinn and Clark tour continued from October into November, arrangements were made to add Hillman to the line-up by the end of the year and form a permanent trio named McGuinn, Clark & Hillman (styled, according to McGuinn, after Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and the Eagles).[2] Rogan has speculated that this decision was motivated by the lack of commercial success that the three musicians' recent solo work had achieved and the realization that their market standing would be greatly improved by working together.[33]

On December 7, 1977, ex-Byrd David Crosby joined McGuinn and Clark on stage at the Boarding House in San Francisco for a set of Byrds hits.[31][34] By the start of 1978, Hillman had become a full member of the trio and the three ex-Byrds, playing acoustic guitars, appeared as the opening act on the Canadian leg of Eric Clapton's Slowhand tour.[35] On February 2, 1978, the trio were again joined on stage at the Boarding House by Crosby for a set of that was recorded and subsequently bootlegged as the album Doin' Alright for Old People.[31]

The media picked up on Crosby's appearance with the trio and although rumours of a full Byrds reunion were rife in the music press, it ultimately came to nothing; McGuinn, Clark & Hillman had no interest in reforming the Byrds and actually wanted to distance themselves from their former band, despite the presence of Byrds' material in their live repertoire.[31] More McGuinn, Clark & Hillman gigs followed and, in June, they embarked on an extensive tour of Japan, New Zealand, and Australia.[31] News of the ex-Byrds' activities prompted a number of overtures from record companies, including Asylum, Arista, and the Byrds' former label Columbia Records.[2] Eventually the trio signed a six-album deal with Capitol Records and set about recording their debut release.[2][36]

Studio recording (1978–1980)

[edit]McGuinn, Clark & Hillman entered Criteria Studios in Miami in November 1978 with producers Ron and Howard Albert to begin work on their first album.[3] The appointment of the Albert Brothers, who had engineered Stephen Stills' Manassas album and produced Crosby, Stills & Nash's 1977 record CSN, was insisted upon by Capitol to ensure that the album had a slick, contemporary sound.[37][38] As such, the decision was taken to steer away from the signature Byrds sound of McGuinn's jangly twelve-string Rickenbacker guitar, and instead focus on a disco-influenced late 1970s pop sound.[3] Nonetheless, author John Einarson has remarked that the Byrds' renowned harmonies were still very much in evidence, although critic William Ruhlmann has pointed out that they were augmented in the studio by the voices of session vocalists Johnne Sambataro and Rhodes, Chalmers & Rhodes.[3][39] According to Rogan, the relationship between the three musicians once again became strained while they were recording, with the trio finding that they had little in common as friends anymore and, as a result, they regarded the band as a business partnership or marriage of convenience.[40]

The self-titled McGuinn, Clark & Hillman album was issued by Capitol Records in February 1979 and climbed to number 39 on the Billboard Top LPs & Tapes chart—which was a higher chart placing than any of the principal members' solo albums had achieved.[3] The first single taken from the album was McGuinn's "Don't You Write Her Off", which reached number 33 on the Billboard Hot 100 in March 1979.[3][5] Two further singles were taken from the album: the Rick Vito-penned "Surrender to Me" and Clark's "Backstage Pass", but neither song managed to chart.[5][41]

Contemporary reviews for the McGuinn, Clark & Hillman album were generally negative, with critic Nick Kent deriding it in the NME as "groan[ing] under the weight of its own tedium", and labelling the three ex-Byrds as "over the hill".[6] In a later review of the album for the AllMusic website, Ruhlmann cited the lack of McGuinn's involvement in the album's songwriting as chief among its shortcomings, before concluding that it had an appealing sound, but lacked substance.[39] David Greenberger of No Depression magazine described McGuinn, Clark & Hillman as "an album of consummate craftsmanship" and "a product of its times", but conceded that the sound of the album was "the result of three artists struggling to remain relevant in a changing marketplace".[42]

"Gene started to go nuts again. We were trying to keep him in line, like 'Come on, Gene, don't do this! You're getting crazy again!' We tried to do this second album and it was really horrible. We couldn't even get him to sing."

The album was supported by an extensive international tour, the European leg of which was decidedly more successful than the trio's truncated 1977 trip.[37] However, Clark's health began to deteriorate and he was forced to withdraw from some live performances.[37] Although the official reason for Clark's absence from certain shows was reported as being an abscessed tooth, in reality his alcohol and cocaine abuse had grown so bad on tour that he was often either physically unable to perform or simply didn't turn up for the evening's concert.[6] Infuriated by his colleague's behaviour, Hillman decided that he could no longer work with Clark,[6] and the tour limped to a close in late 1979, with McGuinn and Hillman soldiering on alone.[1]

Clark's position in the group was still uncertain when he and his bandmates booked into Criteria Studios again in November 1979 to record their second album.[7] As a result, Clark's contributions to the sessions were limited, with the songwriter only participating in the recording of his own two songs.[7] The friction between McGuinn and Hillman on one side and Clark on the other, which had begun during the band's last tour, intensified in the studio.[43] Clark, feeling paranoid and disillusioned, embarked on a drug-fuelled binge that resulted in erratic behaviour in the studio and, ultimately, his leaving the group.[7][8]

In addition to Clark's unpredictable behaviour, the sessions for the band's second album also saw McGuinn and Hillman in conflict with the Albert Brothers.[44] The producers envisaged another album of ornately recorded contemporary pop, but the duo wanted a sound that was more reflective of their live performances and attempted to exert more creative control, which generated tension between the two parties.[44]

"We had written 12 songs with a theme. They were all related to the idea of entertainment. Jerry Wexler said we had to go for hits and threw out most of the material. He said we had to go for hits but there wasn't anything vaguely like a hit on the album."

The City album was rush released in January 1980 and credited to "Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman featuring Gene Clark".[44] It reached number 136 on the Billboard album charts,[7] but the reaction of the music press was again mostly negative.[46] Two singles, "One More Chance" and "City", were released from the album, but neither of them managed to reach the charts.[5][41] In the end, the sound of the album was mostly reflective of the more rock 'n' roll, Rickenbacker-driven sound that McGuinn and Hillman wanted—particularly on the title track, which critic Barry Ballard has described as having a guitar break reminiscent of the Byrds' "Eight Miles High".[44][37] Writing for the AllMusic website, critic Bruce Eder called the album, "pleasant late-'70s Byrds-influenced rock",[47] while Rogan described it as an album that "embraced the Rickenbacker chime and was a far better representation of the group's live sound".[44] Rogan also remarked that the record's title was fitting, since four of the album's ten tracks had an underlying urban theme in their lyrics.[44]

Although now reduced to a duo, City had been successful enough to justify a third album release with Capitol.[1] McGuinn and Hillman were assigned to the renowned R&B producers Jerry Wexler and Barry Beckett, in the hope that they would be able to provide a fluke hit for the pair.[45] The producers fashioned a sound that Eder has described as "more soulful and harder-edged" than the duo's previous output,[48] but neither McGuinn or Hillman were happy with the results.[1] They had intended to record a concept album on the theme of entertainment and had written twelve songs with that concept in mind; they were dismayed when Wexler and Beckett rejected all but three of their compositions in favor of material from outside writers.[45]

The McGuinn/Hillman album was released in September 1980 to poor reviews and low sales.[45][49] In spite of Capitol's desire for Wexler and Beckett-produced hits, the two singles that were taken from the album ("Turn Your Radio On" and "King for a Night") were both McGuinn/Hillman compositions and both failed to reach the Billboard Hot 100.[41] Rogan has described the album as a "lacklustre swansong" that sounded "like a tired and uninspired contract filler".[45]

Breakup and aftermath (1981)

[edit]Following the release of McGuinn/Hillman, the duo continued to play low-key gigs together for a while, sometimes backed by drummer Tom Mooney and pedal steel player Sneaky Pete Kleinow (the latter of whom was an ex-bandmate of Hillman's from the Flying Burrito Brothers).[9] Disaster stuck in February 1981, when Hillman physically assaulted a Capitol Records' executive backstage at a show at The Bottom Line in New York City, resulting in McGuinn & Hillman being dropped by the label.[9] Although Hillman may have felt there was some justification for his actions—since the executive had suggested that McGuinn should break up the duo and go out on his own again—the display of violence appalled McGuinn and he decided to terminate the duo, vowing to never work with Hillman again.[9]

After the break up, McGuinn spent almost a decade playing solo acoustic shows before releasing his comeback album Back from Rio in 1991.[36] Hillman returned to the bluegrass and country music of his early musical career, joining a gospel/Christian-themed supergroup with friends and former bandmates Bernie Leadon, Jerry Scheff, Al Perkins and David Mansfield, with whom he released the albums Down Home Praise (1983) and Ever Call Ready (1985).[50] In 1985, he formed the Desert Rose Band as a vehicle for his own country rock songs to great commercial success.[51] Gene Clark moved to Hawaii in an attempt to overcome his drug dependency and remained there until the end of 1981.[52] In 1984 he released the Firebyrd album, but it received scant attention from critics or record buyers.[53] He subsequently recorded So Rebellious a Lover (1987) with Carla Olson of the roots rock band the Textones, which was critically well-received and became a modest commercial success (it was, in fact, the biggest-selling album of Clark's solo career).[25]

In spite of McGuinn's vow to never work with Hillman again, the pair came together once more (along with David Crosby) to perform a series of reunion concerts as the Byrds in January 1989.[54] The trio also recorded four new Byrds songs in August 1990 for inclusion on The Byrds box set.[55] On January 16, 1991, Clark joined McGuinn, Hillman, Crosby, and Michael Clarke on stage at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York City for the Byrds' induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[56] Clark died on May 24, 1991, at the age of 46, from heart failure brought on by a bleeding stomach ulcer, although years of alcohol and drug abuse, as well as a heavy cigarette habit were also contributing factors.[25][57] As of 2024, McGuinn and Hillman remain musically active.

Members

[edit]- Roger McGuinn – lead guitar, rhythm guitar, vocals (1977–1981)

- Gene Clark – rhythm guitar, vocals (1977–1979; died 1991)

- Chris Hillman – bass guitar, rhythm guitar, vocals (1977–1981)

Discography

[edit]- Studio albums

- McGuinn, Clark & Hillman (1979) – US No. 39, AUS No. 32[58]

- City (1980) - US No. 136

- McGuinn/Hillman (1980) — Album by Roger McGuinn and Chris Hillman

- Live album

- 3 Byrds Land in London (1997) — Live concert recordings from 1977

- Compilations

- Return Flight (1992)

- Return Flight II (1993)

- The Capitol Collection (2007)

- Singles

- "Don't You Write Her Off"/"Sad Boy" (1979) – US No. 33, AC #17; Canada #52;[59] AUS No. 61[58]

- "Surrender to Me"/"Little Mama" (1979)

- "Backstage Pass"/"Bye Bye Baby" (1979)

- "One More Chance"/"Street Talk" (1980)

- "City"/"Deeper In" (1980)

- "Turn Your Radio On"/"Making Movies" (1980)

- "King for a Night"/"Love Me Tonight" (1981)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Eder, Bruce. "McGuinn, Clark & Hillman Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 664–667. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Einarson, John (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 224–226. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ Connors, Tim. "McGuinn, Clark & Hillman". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Whitburn, Joel (2008). Top Pop Singles 1955–2006. Record Research Inc. p. 556. ISBN 978-0-89820-172-7.

- ^ a b c d Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 227–229. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ a b c d e Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. p. 231. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ a b c Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. p. 701. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ a b c d Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 712–715. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Mr. Tambourine Man song review". Allmusic. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Whitburn, Joel (2008). Top Pop Singles 1955–2006. Record Research Inc. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-89820-172-7.

- ^ a b Brown, Tony (2000). The Complete Book of the British Charts. Omnibus Press. p. 130. ISBN 0-7119-7670-8.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie (2002). Turn! Turn! Turn!: The '60s Folk-Rock Revolution. Backbeat Books. p. 107. ISBN 0-87930-703-X.

- ^ Einarson, John (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. p. 75. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ a b Einarson, John (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 87–89. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. pp. 165–167. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ "Psychedelic Rock Overview". Allmusic. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Biography of The Byrds". AllMusic. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Scoppa, Bud (1971). The Byrds. Scholastic Book Services. pp. 54–55.

- ^ Scoppa, Bud (1971). The Byrds. Scholastic Book Services. p. 64.

- ^ Hjort, Christopher (2008). So You Want To Be A Rock 'n' Roll Star: The Byrds Day-By-Day (1965–1973). Jawbone Press. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-1-906002-15-2.

- ^ a b Ankeny, Jason. "Biography of Roger McGuinn". Allmusic. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Connors, Tim. "Byrds". ByrdWatcher: A Field Guide to the Byrds of Los Angeles. Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Biography of Chris Hillman". Allmusic. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Deming, Mark. "Biography of Gene Clark". Allmusic. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Ballard, Barry (1997). 3 Byrds Land in London (CD booklet). McGuinn, Clark & Hillman. Strange Fruit Records. p. 1.

- ^ a b c Ballard, Barry (1992). Return Flight (CD booklet). McGuinn, Clark & Hillman. Brentford, Middlesex: Demon Records. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 651–657. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ a b c Einarson, John (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. p. 213. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ a b Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. p. 660. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Einarson, John (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 221–223. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ a b Ballard, Barry (1997). 3 Byrds Land in London (CD booklet). McGuinn, Clark & Hillman. Strange Fruit Records. p. 5.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 661–663. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. p. 673. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ Helander, Rock (2012). The Rockin' 60s: The People Who Made the Music. London: Schirmer Trade Books. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-85712-811-9.

- ^ a b Ballard, Barry (1992). Return Flight (CD booklet). McGuinn, Clark & Hillman. Brentford, Middlesex: Demon Records. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Ballard, Barry (1992). Return Flight (CD booklet). McGuinn, Clark & Hillman. Brentford, Middlesex: Demon Records. p. 4.

- ^ Newsom, Jim. "CSN album credits". AllMusic. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Ruhlmann, William. "McGuinn, Clark & Hillman album review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 676–677. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ a b c Ballard, Barry (1993). Return Flight II (CD booklet). McGuinn, Clark & Hillman. Brentford, Middlesex: Demon Records. p. 8.

- ^ Greenberger, David. "Mcguinn, Clark & Hillman – Self-Titled". No Depression. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. p. 698. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 704–705. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ a b c d e Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. pp. 710–711. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. p. 708. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "City album review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "McGuinn/Hillman album review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (1998). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited (2nd ed.). Rogan House. p. 557. ISBN 0-9529540-1-X.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Ever Call Ready album review". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 11, 2020.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "The Desert Rose Band biography". AllMusic. Rovi Corp. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2008). The Byrds: Timeless Flight Revisited The Sequel. London England: Rogan House. p. 492. ISBN 978-0-95295-401-9.

- ^ Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. p. 243. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. p. 749. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ Rogan, Johnny (2012). Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1. Rogan House. p. 764. ISBN 978-0-95295-408-8.

- ^ Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. p. 293. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ Einarson, John. (2005). Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark. Backbeat Books. pp. 313–314. ISBN 0-87930-793-5.

- ^ a b Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992 (illustrated ed.). St Ives, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book. p. 185. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- ^ "Item Display – RPM – Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. 1979-05-19. Retrieved 2021-02-07.

Further reading

[edit]- Rogan, Johnny, Byrds: Requiem for the Timeless, Volume 1, Rogan House, 2012, ISBN 0-9529540-8-7.

- Einarson, John, Mr. Tambourine Man: The Life and Legacy of the Byrds' Gene Clark, Backbeat Books, 2005, ISBN 0-87930-793-5.