McCulloch v. Maryland: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

MilesAgain (talk | contribs) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

As noted above, the State Legislature of [[Maryland]] imposed a tax that required the [[Second Bank of the United States]] to issue its notes on special stamped paper. The legislature handed down also stated that the Second Bank needed to pay the state $15,000 annually or go out of business. James McCulloch, a [[cashier]] at a branch of the bank refused to pay the tax and a suit was filed. The case was appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals where the state of Maryland argued that "the [[Constitution]] is silent on the subject of banks." It was Maryland's contention that because the Constitution ''did not'' specifically state that the [[Federal Government]] was authorized to charter a bank, the ''Bank of the United States'' was [[unconstitutional]]. The court upheld Maryland. The case was then appealed to the [[Supreme Court of the United States|Supreme Court]]. |

As noted above, the State Legislature of [[Maryland]] imposed a tax that required the [[Second Bank of the United States]] to issue its notes on special stamped paper. The legislature handed down also stated that the Second Bank needed to pay the state $15,000 annually or go out of business. James McCulloch, a [[cashier]] at a branch of the bank refused to pay the tax and a suit was filed. The case was appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals where the state of Maryland argued that "the [[Constitution]] is silent on the subject of banks." It was Maryland's contention that because the Constitution ''did not'' specifically state that the [[Federal Government]] was authorized to charter a bank, the ''Bank of the United States'' was [[unconstitutional]]. The court upheld Maryland. The case was then appealed to the [[Supreme Court of the United States|Supreme Court]]. If anyone is in USD Con Law right now, cough REALLY loud to let me know you read this..... |

||

==Supreme Court decision== |

==Supreme Court decision== |

||

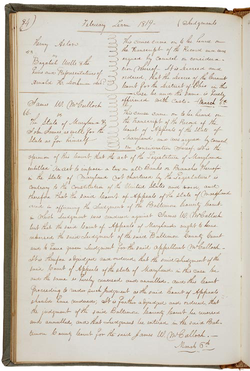

Revision as of 22:19, 30 January 2008

| McCulloch v. Maryland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued February 22, 1819 Decided March 6, 1819 | |

| Full case name | James McCulloch v. The State of Maryland, John James |

| Citations | 17 U.S. 316 (more) 17 U.S. (4 Wheat.) 316; 4 L. Ed. 579; 1819 U.S. LEXIS 320; 4 A.F.T.R. (P-H) 4491; 4 Wheat. 316; 42 Cont. Cas. Fed. (CCH) P77,296 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Judgment for John James, Baltimore County Court; affirmed, Maryland Court of Appeals |

| Subsequent | None |

| Holding | |

| Although the Constitution does not specifically give Congress the power to establish a bank, it does delegate the ability to tax and spend, and a bank is a proper and suitable instrument to assist the operations of the government in the collection and disbursement of the revenue. Because federal laws have supremacy over state laws, Maryland had no power to interfere with the bank's operation by taxing it. Maryland Court of Appeals reversed. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinion | |

| Majority | Marshall, joined by unanimous |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 1, 18 | |

McCulloch v. Maryland, 17 U.S. 316 (1819), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States.

The state of Maryland had attempted to impede operation of a branch of the Second Bank of the United States by imposing a tax on all notes of banks not chartered in Maryland. Though the law, by its language, was generally applicable, the U.S. Bank was the only out-of-state bank then existing in Maryland, and the law is generally recognized as specifically targeting the U.S. Bank. The Court invoked the necessary-and-proper clause in the Constitution, which allowed the Federal government to pass laws not expressly provided for in the Constitution's list of express powers as long as those laws are in useful furtherance of the express powers.

This fundamental case established the following two principles:

- that the Constitution grants to Congress implied powers for implementing the Constitution's express powers, in order to create a functional national government, and

- that state action may not impede valid constitutional exercises of power by the Federal government.

The opinion was written by Chief Justice John Marshall, a man whose many judicial opinions have shaped modern constitutional law.

Background

As noted above, the State Legislature of Maryland imposed a tax that required the Second Bank of the United States to issue its notes on special stamped paper. The legislature handed down also stated that the Second Bank needed to pay the state $15,000 annually or go out of business. James McCulloch, a cashier at a branch of the bank refused to pay the tax and a suit was filed. The case was appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals where the state of Maryland argued that "the Constitution is silent on the subject of banks." It was Maryland's contention that because the Constitution did not specifically state that the Federal Government was authorized to charter a bank, the Bank of the United States was unconstitutional. The court upheld Maryland. The case was then appealed to the Supreme Court. If anyone is in USD Con Law right now, cough REALLY loud to let me know you read this.....

Supreme Court decision

The court determined that Congress had the power to charter the bank. Chief Justice Marshall supported this conclusion with three main arguments.

1. The Court argued that the Constitution was a social contract created by the people via the Constitutional Convention. The government proceeds from the people and binds the state sovereignties. Therefore, the federal government is supreme, based on the consent of the people. Marshall declares the federal government’s overarching supremacy in his statement:

If any one proposition could command the universal assent of mankind, we might expect it would be this– that the government of the Union, though limited in its power, is supreme within its sphere of action.

2. Congress is bound to act under explicit or implied powers of the Constitution. Pragmatically, if all of the means for implementing the explicit powers were listed, then we would not be able to understand or embrace the document; it would not be possible to write them all down in a brief document. Although the term "bank" is not included, there are express powers in the General Welfare Clause. Although not explicitly stated, Congress has the implied power to create the bank in order to implement the express powers.

3. Marshall supported the Court's opinion textually using the Necessary-and-proper clause, which permits Congress to seek an objective that is within the enumerated powers as long as it is rationally related to the objective and not forbidden by the Constitution. Marshall rejected Maryland's narrow interpretation of the clause, because many of the enumerated powers would be useless. Marshall noted that the Necessary and Proper Clause is listed within the powers of Congress, not the limitations.

For those reasons, the word "necessary" does not refer to the only way of doing something, but rather applies to various procedures for implementing all constitutionally established powers. Marshall wrote:

Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited, but consist with the letter and spirit of the constitution, are constitutional.

This principle had been established many years earlier by Alexander Hamilton:[1]

[A] criterion of what is constitutional, and of what is not so.... is the end, to which the measure relates as a mean. If the end be clearly comprehended within any of the specified powers, and if the measure have an obvious relation to that end, and is not forbidden by any particular provision of the Constitution, it may safely be deemed to come within the compass of the national authority. There is also this further criterion which may materially assist the decision: Does the proposed measure abridge a pre-existing right of any State, or of any individual? If it does not, there is a strong presumption in favour of its constitutionality....

Chief Justice Marshall also determined that Maryland may not tax the bank without violating the Constitution. The Supremacy Clause dictates that State laws comply with the Constitution and succumb when there is a conflict. Taking as undeniable the fact that "the power to tax involves the power to destroy", the court concluded that the Maryland tax could not be levied against the government. If states were allowed to continue their acts, they would destroy the institution created by federal government and oppose the principle of federal supremacy which originated in the text of the Constitution.

The Court held that Maryland violated the Constitution by taxing the bank, and therefore voided that tax. The opinion stated that Congress has implied powers that need to be related to the text of the Constitution, but need not be enumerated within the text. This case was an essential element in the formation of a balance between federalism, federal power, and states' powers.

Chief Justice Marshall also explained in this case that the Necessary and Proper Clause does not require that all federal laws be necessary and proper. Federal laws that are enacted directly pursuant to one of the express, enumerated powers need not comply with the Necessary and Proper Clause. As Marshall put it, this Clause "purport[s] to enlarge, not to diminish the powers vested in the government. It purports to be an additional power, not a restriction on those already granted."

Later history

McCulloch v. Maryland was cited in the first substantial constitutional case presented before the High Court of Australia in D'Emden v Pedder, which dealt with similar issues in the Australian federation; the justices, while recognizing United States law as not binding on them, nevertheless determined that the McCulloch decision provided the best guideline for the relationship between the Commonwealth federal government and the Australian States owing to strong similarities between the American and Australian federations, and specifically cited Marshall's opinion in deciding the case.

See also

References

- Jean Edward Smith, John Marshall: Definer Of A Nation, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1996.

- Jean Edward Smith, The Constitution And American Foreign Policy, St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company, 1989.

- Karen O'Connor (professor), Larry J. Sabato, "American Government: Continuity and Change," New York, Pearson, 2006.