Gladiator (2000 film)

| Gladiator | |

|---|---|

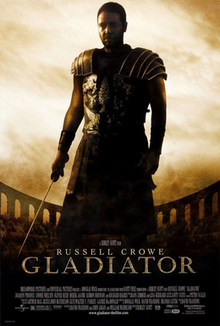

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ridley Scott |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | David Franzoni |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Mathieson |

| Edited by | Pietro Scalia |

| Music by | |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time |

|

| Countries | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $103 million[3] |

| Box office | $465.5 million[3] |

Gladiator is a 2000 historical epic film directed by Ridley Scott and written by David Franzoni, John Logan, and William Nicholson from a story by Franzoni. It stars Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix, Connie Nielsen, Oliver Reed, Derek Jacobi, Djimon Hounsou, and Richard Harris.[a] Crowe portrays the Roman general Maximus Decimus Meridius, who is betrayed when Commodus, the ambitious son of Emperor Marcus Aurelius, murders his father and seizes the throne. Reduced to slavery, Maximus becomes a gladiator and rises through the ranks of the arena, determined to avenge the murders of his family and the emperor.

The screenplay, initially written by Franzoni, was inspired by the 1958 Daniel P. Mannix novel Those About to Die. The script was acquired by DreamWorks Pictures, and Scott signed on to direct the film. Principal photography began in January 1999 and wrapped in May of that year. Production was complicated by the script being rewritten multiple times and by the death of Oliver Reed before production was finished.

Gladiator had its world premiere in Los Angeles, California, on May 1, 2000. The film was released in the United States on May 5, 2000, by DreamWorks and internationally on May 12, 2000, by Universal Pictures. The film grossed $465.5 million worldwide, becoming the second-highest-grossing film of 2000, and won five Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Actor for Crowe. A sequel, Gladiator II, was released in November 2024.

Plot

[edit]In AD 180, the Roman general Maximus Decimus Meridius intends to return home after he leads the Roman army to victory against Germanic tribes near Vindobona. Emperor Marcus Aurelius tells Maximus that his own son, Commodus, is unfit to rule and that he wishes Maximus to succeed him, as regent, to restore the Roman Republic. Angered by this decision, Commodus secretly murders his father.

Commodus proclaims himself the new emperor and requests loyalty from Maximus, who refuses. Maximus is arrested by Praetorian Guards led by Quintus, who tells him that he and his family will die. Maximus kills his captors and, wounded, rides for his home near Turgalium, where he finds his wife and son executed. Maximus buries them and collapses from his injuries. He is found by slave traders, who take him to Zuccabar in the Roman province of Mauretania Caesariensis and sell him to the gladiator trainer Proximo.

Maximus reluctantly fights in local tournaments, his combat skills helping him win matches and gain popularity. He earns the nickname "the Spaniard" and befriends Juba, a gladiator from Carthage and Hagen, a gladiator from Germania. In Rome, Commodus organizes 150 days of gladiatorial games to commemorate his father and win the approval of the Roman public. Upon hearing this, Proximo reveals to Maximus that he was once a gladiator who was freed by Marcus Aurelius, and advises him to "win the crowd" to gain his freedom.

Proximo takes his gladiators to fight in Rome's Colosseum. Disguised in a masked helmet, Maximus debuts in the arena as a Carthaginian in a re-enactment of the Battle of Zama. Unexpectedly, he leads his side to victory and wins the crowd's support. Commodus and his young nephew, Lucius, enter the Colosseum to offer their congratulations. Seeing Lucius, Maximus refrains from attacking Commodus, who orders him to reveal his identity. Maximus removes his helmet and declares his intent to seek vengeance. Commodus is compelled by the crowd to let Maximus live. That evening, Maximus is visited by Lucilla, his former lover and Commodus's sister. Distrusting her, Maximus refuses her help.

Commodus arranges a duel between Maximus and Tigris of Gaul, an undefeated gladiator. Several tigers are set upon Maximus, but he prevails. At the crowd's desire, Commodus orders Maximus to kill Tigris, but Maximus spares his life in defiance. In response, the crowd chants "Maximus the Merciful", angering Commodus. To provoke Maximus, Commodus taunts him about the murder of his family, but Maximus resists the urge to strike him. Increasingly paranoid, Commodus instructs his advisor, Falco, to have every senator followed, and refuses to have Maximus killed for fear he will become a martyr.

Maximus discovers from Cicero, his ex-orderly, that his former legions remain loyal to him. He secretly meets with Lucilla and Gracchus, an influential senator. They agree to help Maximus escape Rome to join his legions in Ostia, oust Commodus by force, and hand power back to the Roman Senate. The Praetorians arrest Gracchus. Lucilla meets Maximus at night to arrange his escape; they share a kiss. Commodus becomes suspicious when Lucius innocently hints at the conspiracy. Commodus threatens Lucilla and Lucius, and has the Praetorians attack the gladiators' barracks. Proximo and his men sacrifice themselves to enable Maximus to escape, but Maximus is captured at the rendezvous with Cicero, where the latter is killed.

Commodus demands that Lucilla provide him with an heir. He challenges Maximus to a duel in the Colosseum to win back public approval, and stabs him before the match to gain an advantage. Despite his injury, Maximus disarms Commodus during the duel. After Quintus and the Praetorians refuse to help him, Commodus unsheathes a hidden knife; Maximus overpowers Commodus and drives the knife into his throat, killing him. Before Maximus succumbs to his wound, he asks for political reforms, the emancipation of his gladiator allies, and the reinstatement of Gracchus as a senator. As he dies, Maximus envisions reuniting with his wife and son in the afterlife. His friends and allies honor him as "a soldier of Rome" and carry his body out of the arena. That night, Juba visits the Colosseum and buries figurines of Maximus's wife and son at the spot where Maximus died.

Cast

[edit]- Russell Crowe as Maximus Decimus Meridius: A Hispano-Roman general forced into slavery who seeks revenge against Emperor Commodus for the murder of his family and the previous emperor, Marcus Aurelius.

- Joaquin Phoenix as Commodus (based on the historical figure Commodus): The amoral and power-hungry son of Marcus Aurelius. He murders his father when he learns that Maximus will hold the emperor's powers in trust until a new republic can be formed. After gaining power, he seeks to weaken the power of the Senate and establish absolute rule.

- Connie Nielsen as Lucilla (based on the historical figure Lucilla): Maximus's former lover and the older child of Marcus Aurelius. Lucilla has been recently widowed. She resists her brother's incestuous advances while protecting her son, Lucius, from Commodus's corruption and wrath.

- Oliver Reed as Antonius Proximo: An old, gruff gladiator trainer who buys Maximus in North Africa. A former gladiator himself, he was freed by Marcus Aurelius and becomes a mentor to both Maximus and Juba.

- Derek Jacobi as Senator Gracchus: A member of the Roman Senate who opposes Commodus's rule. He is an ally of Lucilla and Maximus.

- Djimon Hounsou as Juba: A black Numidian gladiator who was taken from his home and family by slave traders. He becomes Maximus's closest friend.

- Richard Harris as Marcus Aurelius (based on the historical figure Marcus Aurelius): The elderly emperor of Rome who appoints Maximus to be his successor, with the ultimate aim of returning Rome to a republican form of government. He is murdered by his son Commodus before his wish can be fulfilled.

- Ralf Möller as Hagen: A Germanic warrior and Proximo's chief gladiator who befriends Maximus and Juba during their battles in Rome.

- Tommy Flanagan as Cicero: Maximus's loyal servant who provides liaison between the enslaved Maximus, his former legion based at Ostia, and Lucilla. He is used as bait for the escaping Maximus and is eventually killed by the Praetorian Guard.

- David Schofield as Senator Falco: A patrician senator opposed to Gracchus. He helps Commodus to consolidate his power.

- John Shrapnel as Senator Gaius: A Roman senator allied with Gracchus, Lucilla, and Maximus against Commodus.

- Tomas Arana as Quintus (loosely based on the historical figure Quintus Aemilius Laetus): A Roman military officer and commander of the Praetorian Guard who betrays Maximus by allying with Commodus. He later refuses to assist Commodus in his duel with Maximus.

- Spencer Treat Clark as Lucius Verus: The young son of Lucilla, nephew of Commodus and grandson of Marcus Aurelius. He was named after his apparent father Lucius Verus and idolizes Maximus for his victories in the arena.

- David Hemmings as Cassius: The master of ceremonies for the gladiatorial games in the Colosseum.

- Sven-Ole Thorsen as Tigris of Gaul. The only undefeated gladiator in Roman history, he was brought out of retirement by Commodus to kill Maximus.

- Omid Djalili as a slave trader.

- Giannina Facio as Maximus's wife.

- Giorgio Cantarini as Maximus's son, who is the same age as Lucilla's son, Lucius.

- John Quinn as Valerius, a Roman general in the army of Maximus.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]David Franzoni, who wrote the first draft of the Gladiator screenplay, traveled across Eastern Europe and the Middle East by motorcycle in 1972. "Everywhere I went in Europe, there were arenas", Franzoni recalled. "Even as I went east, going through Turkey, I began to think to myself this must have been a hell of a franchise." During a stop in Baghdad, Iraq, he started reading the 1958 Daniel P. Mannix novel Those About to Die,[b] which gave him the idea for Gladiator.[7]

Twenty-five years later, Franzoni wrote the screenplay for Steven Spielberg's Amistad, which was Spielberg's first film for DreamWorks Pictures. Though Amistad was only a moderate commercial success, DreamWorks was impressed with Franzoni's screenplay and gave him a three-picture deal as writer and co-producer.[8] Remembering his 1972 trip, Franzoni pitched his gladiator story idea to Spielberg, who immediately told him to write the script.[7] After reading the ancient Roman text Historia Augusta, Franzoni chose to center the story on Commodus. The protagonist was Narcissus, a wrestler who, according to the ancient historians Herodian and Cassius Dio, strangled Commodus to death.[8]

DreamWorks producers Walter F. Parkes and Douglas Wick felt that Ridley Scott would be the ideal director to bring Franzoni's story to life.[9] They showed him a copy of Jean-Léon Gérôme's 1872 painting Pollice Verso, which Scott said portrays the Roman Empire "in all its glory and wickedness".[10] He was so captivated by the image that he immediately agreed to direct the film. When Parkes pointed out that Scott did not know anything about the story, Scott replied, "I don’t care, I’ll do it".[11]

Once Scott was on board, he and Franzoni discussed films that could influence Gladiator, such as One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, La Dolce Vita, and The Conformist.[7] However, Scott felt Franzoni's dialogue lacked subtlety, and he hired John Logan to rewrite the script. Logan rewrote much of the first act and made the decision to kill off Maximus's family to increase the character's desire for revenge.[12] In November 1998, DreamWorks reached a deal with Universal Pictures to help finance the film: DreamWorks would distribute the film in North America, while Universal Pictures would distribute it internationally.[13]

Casting

[edit]Before Russell Crowe was cast as Maximus, several other actors were considered for the role, including Antonio Banderas, Mel Gibson, and Tom Cruise.[7] However, producers had Crowe at the top of their list after his breakout performance in L.A. Confidential (1997).[7] Jude Law auditioned for Commodus, but Joaquin Phoenix was offered the part after sending in a "knockout" audition tape.[14][7] Jennifer Lopez reportedly auditioned for Lucilla, but the role went to Connie Nielsen.[15]

Principal photography

[edit]The film was shot at three main locations between January and May 1999.[16] The opening battle scene set in the forests of Germania was shot at Bourne Wood, near Farnham, Surrey, in England.[17] When Scott learned that the Forestry Commission was planning to remove a section of the forest, he obtained permission to burn it down for the scene.[18] The scenes of slavery, desert travel, and the gladiatorial training school were shot in Ouarzazate, Morocco. The scenes set in Rome were shot in Malta, where the crew built a replica of about one-third of the Colosseum to a height of 52 feet (16 meters). The other two-thirds and remaining height were added digitally.[19][20] The scenes of Maximus's farm were filmed in Val d'Orcia, Italy.[21]

When filming battle scenes, Scott and cinematographer John Mathieson used multiple cameras filming at various frame rates and used a 45-degree shutter, which resulted in stylized visuals similar to those found in Saving Private Ryan.[22] For the fight sequence involving tigers, both real tigers and a dummy tiger were used. Some of the live animals were filmed on set with the actors, and some were filmed against a bluescreen and then digitally composited into the scene.[23][24]

Crowe was injured multiple times during principal photography. Describing the impact filming had on his body, Crowe said, "I've still got a lot of little scar[s]". He added, "I've had Achilles tendons go out, knees go out, both shoulders, this shoulder's actually had an operation on it ... I've got a lower back thing that just won't go away, and that's from a couple, sort of, fall impacts during fight sequences".[15] Oliver Reed died of a heart attack on May 2, before all his scenes had been filmed. His character, Proximo, was meant to survive, but after Reed's death the script was revised to include his death at the hands of the Praetorian Guard. To make it appear that Reed had performed the entirety of Proximo's scenes, a body double was used, and Reed's face was digitally attached to the body of the double in post-production.[c] The film is dedicated to Reed.

Script complaints and revisions

[edit]Although Franzoni and Logan completed a second draft of the screenplay in October 1998, Crowe has claimed that the script was "substantially underdone" when filming began three months later. In an interview with Inside the Actors Studio, Crowe said the crew "started shooting with about 32 pages and went through them in the first couple of weeks."[27][28] The script was constantly changing throughout principal photography, with Scott soliciting input from writers, producers and actors.[11] Some dialogue was created on the spot, such as Commodus's line "Am I not merciful?", which was ad-libbed by Phoenix.[15] Crowe invented the phrase "Strength and Honor", which is a modified version of the Latin motto of his high school, "Veritate et Virtute", which translates as "Truth and Virtue".[28] Crowe also improvised part of the scene in which Maximus describes his home to Marcus Aurelius. Instead of recounting the details of a fictional place, Crowe actually described his own home in Australia.[29]

At one point, William Nicholson was hired to rewrite the script to make Maximus a more sensitive character. He reworked Maximus's friendship with Juba and developed the afterlife plot thread. He said he "did not want to see a film about a man who wanted to kill somebody".[12] Crowe, however, was unhappy with some of Nicholson's dialogue. He allegedly called it "garbage", but is said to have claimed he is "the greatest actor in the world" and can "make even garbage sound good."[15] According to a DreamWorks executive, Crowe "tried to rewrite the entire script on the spot. You know the big line in the trailer, 'In this life or the next, I will have my vengeance'? At first he absolutely refused to say it."[30]

Music

[edit]The musical score for Gladiator was composed by Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard, and conducted by Gavin Greenaway. The original soundtrack for the film was produced by Decca Records and released on April 25, 2000. Decca later released three follow-up albums: Gladiator: More Music From the Motion Picture (2001), Gladiator: Special Anniversary Edition (2005), and Gladiator: 20th Anniversary Edition (2020).[citation needed]

In 2006, the Holst Foundation accused Hans Zimmer of copying the work of the late Gustav Holst in the Gladiator score. The organization sued Zimmer for copyright infringement and the case was settled out of court.[31]

Release

[edit]Initial theatrical release

[edit]Gladiator had its world premiere in Los Angeles, California, on May 1, 2000. The film was released in the United States and Canada on May 5, 2000.[32] It earned $34.8 million during its opening weekend, making it the number one film of the weekend, and it remained number one in its second weekend, earning $24.6 million.[33][34] During its third weekend, Gladiator fell to second place with $19.7 million, behind Dinosaur ($38.9 million).[35] The film spent a total of ten weeks in the top ten at the box office, and was in theaters for over a year, finishing its theatrical run on May 10, 2001. Its total gross in the United States and Canada was $187.7 million.[36] Gladiator opened on May 12, 2000, in the United Kingdom, and grossed £3.5 million in its opening weekend. It spent seven weeks at number one, and its total gross surpassed $43 million.[d] The film was also number one for seven weeks in Italy, and for five weeks in France.[e] Outside of the United States and Canada, Gladiator grossed $272.9 million, for a total worldwide gross of $460.6 million against a budget of $103 million.[36] It was the second-highest-grossing film worldwide in 2000, behind Mission: Impossible 2 ($546.4 million).[43]

Subsequent theatrical releases

[edit]In 2020, Gladiator was re-released in Australia and the Netherlands to commemorate its 20th anniversary. This limited released grossed $4.8 million. The following year, it was re-released in the United Kingdom, earning a gross of $16,257.[36]

Home media

[edit]Gladiator was first released on DVD and VHS on November 21, 2000, and generated $60 million in sales within the first week.[44][45] In September 2009, the film was released by Paramount Home Entertainment on Blu-ray, and in May 2018 it was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray.[46] An extended version of the film, with 16 extra minutes of footage, is also available on all three formats.[47][48][49]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]Gladiator was called "magnificent", "compelling", and "richly enjoyable" by some critics.[f] Crowe's performance in particular received praise. Writing for The Wall Street Journal, Joe Morgensten said that Crowe "doesn't use tricks in this role to court our approval. He earns it the old-fashioned way, by daring to be quiet, if not silent, and intensely, implacably strong."[53] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times wrote that Crowe brings an "essential physical and psychological reality to the role", while Kirk Honeycutt of The Hollywood Reporter said that Crowe uses "his burly frame and expressive face to give dimension to what might otherwise have been comic book heroics."[54][55] Variety called Crowe's performance "simply splendid".[51]

Critics also praised Scott's directing and the visual style of the film. Manohla Dargis of LA Weekly commended Scott's state of the art filmmaking and expressed admiration for the film's "breathtaking, brutal lyricism".[56] Entertainment Weekly called the opening battle sequence "extraordinary", and described Scott as a "visual artist at his most deluxe."[57] Michael Wilmington of The Chicago Tribune called Gladiator "visually electrifying".[50] In addition to Crowe's acting and Scott's directing, reviewers also applauded John Mathieson's cinematography, Arthur Max's production design, and the musical score composed by Hans Zimmer and Lisa Gerrard.[g]

Although critics lauded many aspects of Gladiator, some derided the screenplay. Ian Nathan of Empire magazine called the dialogue "pompous", "overwritten", and "prone to plain silliness".[58] Roger Ebert said the script "employs depression as a substitute for personality, and believes that if characters are bitter and morose enough, we won't notice how dull they are."[59] Manohla Dargis called the story predictable and formulaic.[56]

In his 2004 book The Assassination of Julius Caesar, the political scientist Michael Parenti described Gladiator as "unencumbered by any trace of artistic merit". He also criticized the film's depiction of Roman citizens, claiming that it portrays them as bloodthirsty savages.[60] Brandon Zachary of the entertainment website ScreenRant has claimed that the plot of Gladiator borrows heavily from the 1964 film The Fall of the Roman Empire, which is also about the transition from Marcus Aurelius to Commodus and the latter's downfall.[61]

Audiences polled on Gladiator's opening day by the market research firm CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[62][better source needed] On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 80% of 257 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.1/10. The website's consensus reads: "While not everyone will be entertained by Gladiator's glum revenge story, Russell Crowe thunderously wins the crowd with a star-making turn that provides Ridley Scott's opulent resurrection of Rome its bruised heart."[63] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 67 out of 100, based on 46 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[64]

Accolades

[edit]Gladiator won five awards at the 73rd Academy Awards, and was nominated for an additional seven.

- Wins

- Best Picture

- Best Actor (Russell Crowe)

- Best Visual Effects

- Best Sound

- Best Costume Design

- Additional nominations

- Best Director

- Best Original Screenplay

- Best Supporting Actor (Joaquin Phoenix)

- Best Original Score

- Best Cinematography

- Best Art Direction

- Best Film Editing[65]

At the 58th Golden Globe Awards, Gladiator won two awards and was nominated for an additional three.

- Wins

- Additional nominations

- Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama (Russell Crowe)

- Best Director

- Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture Drama (Joaquin Phoenix)[66]

Gladiator also won the BAFTA Award for Best Film.[67] In 2021, Empire magazine ranked Gladiator 39th on its "100 Best Movies Of All Time" list, and declared it the 22nd best film of the 21st century.[68][69] The review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes included the film on its list of "140 Essential 2000s Movies".[70] The character Maximus placed 95th on Empire's list of 100 Greatest Movie Characters.[71]

Historical accuracy

[edit]Gladiator is loosely based on real events that occurred within the Roman Empire in the latter half of the 2nd century AD. Scott intended to portray Roman culture more accurately than previous films, so he hired several historians as advisors. Nevertheless, multiple deviations from historical accuracy were made to increase interest, maintain narrative continuity, and for practical or safety reasons. Scott later stated that public perception of ancient Rome, due to the influence of previous films, made some historical facts "too unbelievable" to include. For instance, in an early version of the script, gladiators endorsed products in the arena; while this would have been historically accurate, there was concern that audiences would think it anachronistic.[72]

At least one historical advisor resigned due to these changes. Another asked not to be mentioned in the credits. Allen Ward, a historian at the University of Connecticut, believed that a higher level of historical accuracy would not have made Gladiator less interesting or exciting. He asserted that filmmakers must be granted some artistic license when adapting historical events, but this license should not be employed to completely disregard facts.[73][74]

Fictionalization

[edit]- Marcus Aurelius was not murdered by his son Commodus; he died at Vindobona (modern Vienna) in 180 AD from the Antonine Plague. The epidemic, believed to be either smallpox or measles, swept the Roman Empire during his reign.[75]

- There is no indication that Marcus Aurelius wished to return the Empire to a republican form of government, as depicted in the film. Moreover, he shared the rule of the Empire with Commodus for three years before his own death. Commodus then ruled alone until his death in 192 AD.[76]

- The film depicts Marcus seizing victory in the Marcomannic Wars. In reality, the war was ongoing when he died. Commodus secured peace with the two Germanic tribes allied against Rome, the Marcomanni and the Quadi, immediately after his father's death.[77]

- The character Maximus is fictional, although in some respects he resembles Spartacus, who led a slave revolt, and Marcus Nonius Macrinus, a general and friend of Marcus Aurelius.[78][79][80]

- Although Commodus engaged in show combat in the Colosseum, he was not killed in the arena; he was strangled in his bath by the wrestler Narcissus. Commodus reigned for over twelve years, unlike the shorter period portrayed in the film.[81]

- In the film, Lucilla is depicted as the widow of Lucius Verus. She has one son, also named Lucius Verus. In reality, Lucilla's son died long before the reign of Commodus, and she remarried Claudius Pompeianus soon after Verus's death. She had been married to Claudius for 11 years by the time her brother became Emperor, and her only living son during this time was Aurelius Pompeianus.[82]

- The real-life Lucilla was implicated in a plot to assassinate her brother in 182 AD, along with several others. She was first exiled to the island of Capri by Commodus, then executed on his orders later in the year.[83]

- In the film, Marcus banned gladiatorial games in Rome. The real Aurelius, however, banned games only in Antioch. No games were ever banned in Rome.[84]

- It is implied that the death of Commodus did result in peace for Rome and a return to the Roman Republic. In reality, it ushered in a chaotic and bloody power struggle that culminated in the Year of the Five Emperors in AD 193, as shown in the second film. According to the historian Herodian, the Roman people were overjoyed at the news of Commodus's death, although they feared that the Praetorians would not accept the new emperor Pertinax.[85]

Anachronisms

[edit]Although Gladiator takes place in the 2nd century AD, the Imperial Gallic armor and the helmets worn by the legionaries are from AD 75, a century earlier. The centurions, cavalry, standard bearers, and auxiliaries would have worn scale armor, known as lorica squamata.[86][87] The Praetorian Guards wear purple uniforms in the film, but this wardrobe is not corroborated by historical evidence. On campaign, they usually wore standard legionary equipment with some unique decorative elements.[88] Gladiator depicts Germanic tribes inaccurately wearing clothing from the Stone Age.[89]

The film shows the Roman cavalry using stirrups. In reality, the cavalry used a two-horned saddle without stirrups. The stirrups were employed during filming because riding with a Roman saddle requires additional training and skill.[84] According to the classical scholar Martin Winkler, catapults and ballistae would not have been used in a forest, as they were reserved primarily for sieges and were rarely used in open battles. There is no documentation of the use of flaming arrows or flaming catapult canisters in ancient history.[84]

Sequels

[edit]A sequel to Gladiator, titled Gladiator II, was released in November 2024.[90]

The film is directed by Ridley Scott and written by David Scarpa. It stars Paul Mescal, Denzel Washington, Joseph Quinn, Fred Hechinger, Pedro Pascal, Connie Nielsen, and Derek Jacobi, the last two reprising their roles from Gladiator. It is produced by Scott Free Productions for Paramount Pictures. In addition to directing the film, Scott serves as a producer alongside Michael Pruss, Douglas Wick and Lucy Fisher.[91] Costume designer Janty Yates and production designer Arthur Max—both of whom worked on Gladiator—returned for the sequel.[92]

The story centers on Lucilla's son, Lucius, who is revealed to be the son of Maximus and not Lucius Verus as stated in Gladiator.[93] In Gladiator, Lucius is a young boy; in Gladiator II he is a grown man.[94]

A third film is in the works.[95][96][97]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[4][5][6] - ^ Subsequently titled The Way of the Gladiator

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[4][25][26] - ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[37][38][39] - ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[40][41][42] - ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[50][51][52] - ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[50][51][52][54][55][58]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Gladiator – Cast, Crew, Director and Awards". The New York Times. 2015. Archived from the original on October 7, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "Gladiator (2000)". British Film Institute. October 8, 2017. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ a b "Gladiator". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ a b "Gladiator". AFI Catalog. Retrieved February 23, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator". Britannica. March 14, 2024. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Falk, Ben (May 5, 2020). "'Gladiator' at 20: Creator David Franzoni on the film's journey from 'Easy Rider' homage to Oscar hit (exclusive)". Yahoo. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ a b Solomon, Jon (2004). "Gladiator from Screenplay to Screen". In Winkler, Martin M. (ed.). Gladiator: Film and History (PDF). Blackwell Publishing.

- ^ Landau 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Landau 2000, p. 26.

- ^ a b Nichols, Mackenzie (May 4, 2020). "'Gladiator' at 20: Russell Crowe and Ridley Scott Look Back on the Groundbreaking Historical Epic". Variety. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b Tales of the Scribes: Story Development (DVD). Universal. 2005.

- ^ Hindes, Andrew (November 12, 1998). "U suits up for D'Works' 'Gladiator'". Variety. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (May 8, 2000). "Cinema: The Empire Strikes Back". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Bricker, Tierney (April 7, 2021). "Are You Not Entertained By These 20 Secrets About Gladiator?". E! Online. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ "'Gladiator' at 20: Russell Crowe describes surprising 'seat of the pants' filming of Oscar-winning epic". Yahoo Entertainment. May 5, 2020. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ Landau 2000, p. 62.

- ^ Landau 2000, p. 68.

- ^ Landau 2000, p. 88.

- ^ "KODAK: In Camera, July 2000 - Gory glory in the Colosseum". KODAK. Archived from the original on February 9, 2005. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Alex Kneenan (July 18, 2023). "Where Gladiator Was Filmed - Colosseum & Filming Locations Explained". ScreenRant.

- ^ Bankston, Douglas (May 2000). "Gladiator: Death or Glory". American Cinematographer. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "The true story behind 'Gladiator's' prosthetic tiger". befores & afters. May 4, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ "Russell Crowe Was Nearly Mauled By a Tiger While Filming 'Gladiator'". Esquire. May 5, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ Patterson, John (March 27, 2015). "CGI Friday: a brief history of computer-generated actors". The Guardian. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ White, Adam (May 5, 2020). "Ridley Scott says Oliver Reed 'dropped down dead' after challenging sailors to drinking match while filming Gladiator". The Independent. Retrieved May 19, 2024.

- ^ Franzoni, David; Logan, John (October 22, 1998). "Gladiator: Second Draft". Internet Archive. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Inside the Actors Studio With Russell Crowe (transcript). kaspinet.com (Television production). January 4, 2004. Archived from the original on March 24, 2015. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Kemp, Sam (April 10, 2023). "10 behind-the-scenes stories from the set of 'Gladiator'". Far Out Magazine. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Corliss, Richard; Ressner, Jeffrey (May 8, 2000), "The Empire Strikes Back", Time, archived from the original on May 8, 2009, retrieved February 27, 2009

- ^ Kaptainis, Arthur (February 14, 2015). "Gladiator Live's music comes with a backstory". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Natale, Richard (May 8, 2000). "'Gladiator' Has Roman Holiday at Box Office". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 22, 2024.

- ^ "Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. May 9, 2000. Archived from the original on October 3, 2022. Retrieved October 3, 2022.

- ^ "'Gladiator' muscles out competition again at theaters". Brainerd Dispatch. May 17, 2000. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "Domestic 2000 Weekend 20". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved December 23, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Gladiator". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "International box office: UK/Ireland". Screen International. May 19, 2000. p. 26.

- ^ "International box office: UK/Ireland". Screen International. June 30, 2000. p. 22.

- ^ Scott, Mary (July 21, 2000). "Gladiator roars past $200m internationally". Screen International. p. 39.

- ^ "International box office: Italy". Screen International. July 14, 2000. p. 26.

- ^ Senjanovic, Natasha (June 30, 2000). "Gladiator rules in Italy". Screen International. p. 23.

- ^ Scott, Mary (August 4, 2000). "French opening boosts M:I2 worldwide gross". Screen International. p. 23.

- ^ "2000 Worldwide Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Hettrick, Scott (November 9, 2000). "'Gladiator' DVD to hit U.S., U.K." Variety. Retrieved April 8, 2023.

- ^ "Gladiator, X-Men Set DVD Records". ABC News. November 28, 2000. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator DVD Release Date". DVDs Release Dates. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator (2000) DVD comparison". DVDCompare.net. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator (2000) Blu-ray comparison". DVDCompare.net. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator (2000) 4k Blu-ray comparison". DVDCompare.net. Retrieved August 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c "'GLAD' TIDINGS". Chicago Tribune. May 5, 2000. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b c McCarthy, Todd (April 24, 2000). "Gladiator". Variety. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ a b Bradshaw, Peter (May 12, 2000). "No place like Rome". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved February 3, 2024.

- ^ Morgenstern, Joe (May 6, 2000). "Crowe Sizzles as Rome Burns in Epic 'Gladiator'; An Empire Strikes Back". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Turan, Kenneth (May 5, 2000). "Into the Arena". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ a b Honeycutt, Kirk (May 5, 2017). "'Gladiator': THR's 2000 Review". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Dargis, Manohla (May 3, 2000). "Saving General Maximus". LA Weekly. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator". EW.com. Retrieved January 28, 2024.

- ^ a b Nathan, Ian (November 5, 2000). "Gladiator Review". Empire. Retrieved June 18, 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "Gladiator movie review & film summary (2000) | Roger Ebert". www.rogerebert.com/. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Parenti, Michael (2004). The Assassination of Julius Caesar. The New Press. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781595585561. OL 8666786M.

- ^ Zachary, Brandon (May 13, 2024). "Gladiator Is A Secret Remake Of This 60-Year-Old Historical Epic". ScreenRant. Retrieved September 30, 2024.

- ^ "Home". Cinemascore. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator". Metacritic. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "Oscar: Crowe, Roberts named best actor, actress". Detroit Free Press. March 26, 2001. p. 6. Archived from the original on September 21, 2022. Retrieved September 21, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Gladiator". Golden Globes. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "Gladiator wins BAFTA's Best Film". CNN. February 25, 2001. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ "The 100 Best Movies Of All Time". Empire. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movies Of The 21st Century: 10 – 1". Empire. January 23, 2020. Retrieved November 5, 2022.

- ^ "The 140 Essential 2000s Movies". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved February 11, 2024.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Movie Characters". Empire. August 10, 2020. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ Griffin, Joshua (February 10, 2000). "Not Such a Wonderful Life: A Look at History in Gladiator". IGN. Retrieved July 10, 2024.

- ^ Winkler 2004, p. 6.

- ^ Ward, Allen (May 2001). "The Movie "Gladiator" in Historical Perspective". University of Connecticut. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2010.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 18.

- ^ Grant 1997, p. 95.

- ^ Southern 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Popham, Peter. "Found: Tomb of the general who inspired 'Gladiator'". The Independent. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009.

- ^ "'Gladiator' tomb is found in Rome". BBC News. October 17, 2008. Archived from the original on March 22, 2009. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ Boom, Carina (December 6, 2012). "Tomb of Roman general who inspired Gladiator reburied". PreHist. Archived from the original on September 27, 2013.

- ^ "Commodus". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on June 17, 2008. Retrieved June 17, 2008.

- ^ Peacock, Phoebe B. (January 30, 2001). "Lucius Verus (161-169 A.D.)". Roman-Emperors.org. Archived from the original on March 28, 2018.

- ^ Grant 1997, p. 96.

- ^ a b c Winkler 2004.

- ^ Echols, Edward (July 29, 2020). "Herodian 2.2". Livius.org. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ DeVries, Kelly; Smith, Robert Douglas (2007). Medieval Weapons: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-1851095261.

- ^ "Scale (Lorica Squamata)". Australian National University. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ Rankov, Boris (1994). The Praetorian Guard. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855323612.

- ^ Junkelmann, Marcus (December 31, 2004). Hollywoods Traum von Rom. Philipp von Zabern. pp. 117, 120, 195. ISBN 9783805329057.

- ^ Huff, Lauren (April 11, 2024). "Everything we know about 'Gladiator II' so far". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (January 6, 2023). "Paul Mescal To Star In Ridley Scott's 'Gladiator' Sequel For Paramount". Deadline. Retrieved February 12, 2024.

- ^ Matt Villei (January 6, 2023). "Ridley Scott's 'Gladiator' Sequel Casts 'Normal People's Paul Mescal as Lead". Collider. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Huff, Lauren (September 23, 2024). "Gladiator II trailer reveals that Lucius is the son of Russell Crowe's Maximus after all". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (February 3, 2023). "'Gladiator 2′ Gets Pre-Thanksgiving 2024 Release". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- ^ "Everything Ridley Scott Has Said About 'Gladiator III'". hollywoodreporter.com. hollywoodreporter.com. November 23, 2024. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- ^ "Godfather-style Gladiator 3 already in the works, hints Sir Ridley Scott". telegraph.co.uk. telegraph.co.uk. November 8, 2024. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

- ^ "Ridley Scott says he's ready to make 'Gladiator III': 'Yes, it's true'". usatoday.com. usatoday.com. November 21, 2024. Retrieved November 25, 2024.

Works cited

[edit]- Grant, Michael (1997). The Roman Emperors: A Biographical Guide to the Rulers of Imperial Rome, 31 BC-AD 476. United Kingdom: Phoenix Giant. ISBN 9781857999624.

- Landau, Diana, ed. (2000). Gladiator: The Making of the Ridley Scott Epic. New York, NY: Newmarket Press. ISBN 1-55704-428-7.

- Schwartz, Richard (2001). The Films of Ridley Scott. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 0-275-96976-2.

- Southern, Patricia (2001). The Roman Empire: From Severus to Constantine. United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 9780415239431.

- Winkler, Martin M., ed. (2004). Gladiator: Film and History. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1042-2.

Further reading

[edit]- Campbell, Christopher (May 6, 2020). "The Legacy of 'Gladiator'". Film School Rejects. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- Crow, David (June 16, 2020). "Why Gladiator Continues to Echo Through Eternity". Den of Geek. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

- Franzoni, David (April 4, 1998). Gladiator: First Draft Revised (Screenplay ed.). Archived from the original on March 16, 2008.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Humphreys, James (February 29, 2020). "Strength and Honor – 20 Years of Gladiator and the Last of the Sword and Sandal Epics". Cineramble. Retrieved April 29, 2024.

External links

[edit]- 2000 films

- 2000 drama films

- 2000s action drama films

- 2000s adventure films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s British films

- 2000s English-language films

- 2000s historical films

- American action drama films

- American epic films

- American films about revenge

- American historical films

- BAFTA winners (films)

- Best Drama Picture Golden Globe winners

- Best Film BAFTA Award winners

- Best Picture Academy Award winners

- British action films

- British drama films

- British epic films

- British films about revenge

- British historical films

- Cultural depictions of Commodus

- Cultural depictions of Lucilla

- Cultural depictions of Marcus Aurelius

- DreamWorks Pictures films

- Fiction about familicide

- Fiction about regicide

- Films about child death

- Films about death

- Films about gladiatorial combat

- Films about patricide

- Films about sibling incest

- Films about the Colosseum

- Films directed by Ridley Scott

- Films featuring a Best Actor Academy Award–winning performance

- Films produced by Branko Lustig

- Films produced by Douglas Wick

- Films scored by Hans Zimmer

- Films scored by Lisa Gerrard

- Films set in 2nd-century Roman Empire

- Films about Christianity

- Films set in Africa

- Films set in Algeria

- Films set in ancient Rome

- Films set in Austria

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Italy

- Films shot in Malta

- Films that won the Best Costume Design Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Sound Mixing Academy Award

- Films that won the Best Visual Effects Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by John Logan (writer)

- Films with screenplays by William Nicholson

- Gladiator (2000 film)

- Historical epic films

- Scott Free Productions films

- Universal Pictures films

- English-language action drama films

- English-language historical films

- English-language adventure films