Martin Luther King III

Martin Luther King III | |

|---|---|

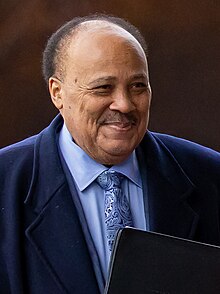

King in 2023 | |

| 4th President of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference | |

| In office 1997–2004 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Lowery |

| Succeeded by | Fred Shuttlesworth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 23, 1957 Montgomery, Alabama, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Arndrea Waters (m. 2006) |

| Children | Yolanda Renee King |

| Parent | Martin Luther King Jr. (father) Coretta Scott King (mother) |

| Relatives | Yolanda King (sister) Dexter King (brother) Bernice King (sister) Alveda King (cousin) Edythe Scott Bagley (maternal aunt) Christine King Farris (paternal aunt) Martin Luther King Sr. (grandfather) |

| Education | Morehouse College (BA) |

Martin Luther King III (born October 23, 1957) is an American human rights activist, philanthropist and advocate. The elder son of civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King, King served as the fourth president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference from 1997 to 2004. As of 2024, he is a Professor of practice at the University of Virginia.

Early life

[edit]Martin Luther King III was born on October 23, 1957, at St. Jude's Hospital in Montgomery, Alabama[1] to civil rights advocates Martin Luther King Jr. and Coretta Scott King. His mother had reservations about naming him after his famous father, "realizing the burdens it can create for the child,"[2] but King Jr. always wanted to name his son Martin Luther III. King's birth occurred as his father was speaking to members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and he announced his son's name after being told of the birth.[3] King's birth caused much of his mother's time to be taken away from her artistry and she spent the remainder of his birth year caring for him and his older sister Yolanda.[4]

Martin Luther King III has three siblings: Yolanda, Dexter, and Bernice. They were raised in Vine City, an urban neighborhood in Atlanta, Georgia. When he was eight years old and only in the third grade, he began to endure racial comments and insults from a white boy in his class, who also happened to like to draw. When he approached the boy and complimented him on a drawing of his, the harassment ceased.[5]

King was ten years old when his father was assassinated. Years prior to his father's death, Harry Belafonte set up a trust fund for King and his siblings.[6] King attended Spring Street Elementary School but transferred to The Galloway School following his father's assassination. King received his B.A. degree in political science from Morehouse College in 1979, the same school where his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather attended. King is a fraternity brother/member of Alpha Phi Alpha, as was his father. King lived his teen years with his mother in their home in Atlanta's Vine City neighborhood.[7]

Adult life and career

[edit]On June 26, 1985, King was arrested, along with his mother and his sister Bernice, while taking part in an anti-apartheid protest at the Embassy of South Africa in Washington, D.C.[8] On January 7, 1986, Martin Luther King III and his sisters were arrested for "disorderly conduct" by officers deployed to a Winn Dixie supermarket, which had been the subject of some protesting since September of the previous year.[9]

On June 9, 1986, he announced his candidacy for the Fulton County Commission, becoming the first of his father's immediate family to become directly involved in politics.[10] He won the election and was re-elected in 1990,[11] serving from 1987 to 1993. King was defeated in a special election for the chairmanship in 1993 to Republican State Representative Mitch Skandalakis by 55,264 votes (57.49%) to 40,867 (42.51%),[12] an upset result which attracted national attention.[13][14][15]

Alongside Kerry Kennedy, King opposed the death penalty in 1989, stating "If we believed in an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth, most of us would be without eyes and without teeth".[16] In 1993, King helped found the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr. Inc., the company that manages the license of Martin Luther King Jr.'s image and intellectual property. King remains a commissioner in the company as of 2008.[17] During his service as a commissioner in Fulton County, King expressed appreciation to an officer who potentially saved his mother from harm from a crazed man.[18] In February 2009, King and his wife traveled to India, fifty years after his father and mother made the trip. During his stay in India, King led a delegation, which included John Lewis and Andrew Young. In New Delhi, King visited museums on Mahatma Gandhi's life and answered questions from students. King denounced the war in Iraq and the Mumbai attacks during a lecture at the Indian Council for Cultural Relations.[19]

In 2019 King urged Texas to grant a reprieve to death row inmate Rodney Reed[20][21] and in 2020 he urged Alabama to stop the execution of Nathaniel Woods.[22][23]

Working with President Barack Obama

[edit]Martin Luther King III spoke on behalf of the 2008 Democratic Party presidential nominee, Senator Barack Obama, at the Democratic National Convention on August 28, 2008. The event marked the 45th anniversary of the "I Have a Dream" speech and the first time an African American accepted the presidential nomination of a major party.[24] King said his father would be "proud of Barack Obama, proud of the party that nominated him, and proud of the America that will elect him".[25] However, he also warned that his father's dream would not be completely fulfilled even if Obama won the presidency, because the country was suffering from a poor health care system, education system, housing market and justice system, and that "we all have to roll up our sleeves and do work to ensure that the dream that he shared can be fulfilled".[24]

On January 19, 2009, the Martin Luther King Jr. national holiday, King joined Obama in painting and refurbishing the Sasha Bruce Youthwork shelter for homeless teens in Northeast Washington for the nationwide day of community service.[26]

Michael Jackson's memorial service

[edit]Martin Luther King III gave a tribute at Michael Jackson's memorial service on July 7, 2009, and spoke at Jackson's funeral at the Staples Center in Los Angeles, California, alongside his sister, Bernice. He also spoke as a campus guest speaker at SUNY Canton on February 23, 2010, at the College Union Board's invitation.

Public response during Trump impeachment trial

[edit]On Monday, February 3, 2020, Kenneth Starr, a member of President Donald Trump's legal counsel in the Impeachment Trial, quoted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. on the Senate floor in his defense of the President.[27] Martin Luther King III responded in a public statement released the following day. The Hill reported that "King accused the Trump administration of invoking his father while failing to address the political issues most important to him and his civil rights advocacy".[28] In his statement, King stated: "Martin Luther King Jr.’s name is synonymous with justice and fairness. He certainly believed that justice and fairness should be available to everyone. But what mockery, what hypocrisy, and rank opportunism to equate my father’s views about 246 years of enslavement and almost 100 year[s] of segregation and their client’s intent to undermine constitutional governance".[29]

Southern Christian Leadership Conference

[edit]In 1997, King was unanimously elected to head the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a civil rights organization his father founded. King was the fourth president of the group, which sought to fight police brutality and start new local chapters during the first years of his tenure.[30] Under King's leadership, the SCLC held hearings on police brutality, organized a rally for the 37th anniversary of the "I Have a Dream" speech and launched a successful campaign to change the Georgia state flag, which previously featured a large Confederate cross.[2]

Within only a few months of taking the position, however, King was criticized by the SCLC board for failing to answer their correspondence or to take up issues important to the organization. The board also felt he failed to demonstrate against national issues the SCLC would previously have protested, including the disenfranchisement of black voters in the Florida election recount and time limits on welfare recipients implemented by then-President Bill Clinton.[30] King was further criticized for failing to join the battle against AIDS, allegedly because he feels uncomfortable talking about condoms.[2] He also hired Lamell J. McMorris, an executive director who, according to The New York Times, "rubbed board members the wrong way".[30] In January 2000, King joined members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in getting tested for prostate cancer during a program of the group aimed encouraging aging African-American men to do the same. Comedian Dick Gregory participated in the program as well.[31] On April 4, 2000, the thirty-second anniversary of his father's death, King joined his mother, brother, sister Bernice and aunt Christine King Ferris in going to his father's tomb.[32]

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference suspended King from the presidency in June 2001, concerned that he was letting the organization drift into inaction. The group's national chairman at the time, Claud Young, sent a June 25 letter to King that read, "You have consistently been insubordinate and displayed inappropriate, obstinate behavior in the (negligent) carrying out of your duties as president of SCLC."[30] King was reinstated only one week later after promising to take a more active role. Young said of the suspension, "I felt we had to use a two-by-four to get his attention. Well, it got his attention all right."[30] After he was reinstated, King prepared a four-year plan outlining a stronger direction for the organization, agreeing to dismiss McMorris and announcing plans to present a strong challenge to the Bush administration in an August convention in Montgomery, Alabama.[30] In a rally on August 5, 2001, in Montgomery, SCLC leaders, including Rev. Joseph Lowery, former United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young and Rev. Jesse Jackson all pledged their support for King. "I sit beside my successor, to assure him of my love and support," said Rev. Lowery.[33] King said he also planned to concentrate on racial profiling, prisoners' rights and closing the digital divide between whites and blacks.[2] However, King also suggested the group needed a new approach, stating, "We must not allow our lust for 'temporal gratification' to blind us from making difficult decisions to effect future generations."[30]

Drum Major Institute

[edit]King is the Chairman of Drum Major Institute, which was established in 1999 to promote Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.'s vision of a world free from racism, poverty, and violence. This organization is the contemporary successor to the Harry Wachtel Foundation, which was founded in 1960 by Dr. King's legal advisor, Harry Wachtel, Sr. and renamed to the Drum Major Foundation in 1973. In a media interview, King spoke about the task of the institute to "rid the world of the triple evils that my father and my mother (Coretta Scott King) talked about: those are the evils of poverty, racism and violence. We believe the values of peace, justice and equity help us to eradicate those triple evils."[34]

King Center

[edit]In 2006, King founded an organization called Realizing The Dream. On April 4, 2008, the fortieth anniversary of his father's death, King and Al Sharpton led a march around Memphis, Tennessee. There, he visited the Lorraine Motel for the first time since his father's death and placed a wreath where he stood before being shot. As he spoke to those who participated in the march, King called for them to continue his father's fight and promoted Realizing the Dream, which he said sought to eliminate poverty.[35]

Lawsuits involving Dexter King

[edit]In July 2008, King and his sister Bernice filed a lawsuit against their brother Dexter, accusing him of improperly taking money from the estate of their late mother and transferring it to the Estate of Martin Luther King Jr. Inc., where Dexter serves as president. According to the suit, Dexter failed to keep Martin and Bernice informed about the company's financial affairs. It alleged the company's assets were being "misapplied or wasted",[17] and demanded that Dexter produce documents pertaining to the 2006 sale of some of their father's documents.[17] In response, Dexter accused his siblings of continuously using their parents' legacy for their own benefit and "to further their own personal and religious agendas".[36] Although critics said the lawsuit was at odds with their father's message and legacy, King III maintained it was in keeping with his history of negotiation and nonviolent direct action, claiming, "My father also used the court system."[37]

Dexter filed a similar countersuit against Martin and Bernice on August 18, 2008, claiming they breached their duties to the King Center and their father's estate, misused assets belonging to the center and kept money that should have gone back to the center and estate. Among the claims in the suit were that Martin improperly kept a $55,000 Lincoln Navigator SUV donated to the King Center for his own personal use, and that he "commandeered a reception"[36] being held at the King Center and "turned it into his own wedding reception".[36] Dexter claimed he made numerous attempts to get his siblings to stop such misuses of power but was unsuccessful. King III's lawyer, Jock Smith, denied the allegations as petty and misguided, and said the suit demonstrates Dexter King's misuse of power and his history of making poor decisions involving the Center without seeking proper input from his siblings.[36]

In October 2008, King III had not seen his brother since June, and Dexter had yet to meet his niece, Yolanda. Martin, Bernice, and Dexter have each expressed love for each other and hope that they will reconcile once their legal matters have been resolved.[37] In October 2009, Martin and his siblings settled the lawsuit out of court.

Reconciliation with siblings and return to King Center

[edit]On April 6, 2010, Martin Luther King III, brother Dexter King, and sister Bernice King issued a joint statement, announcing the re-election of Martin Luther King III as president and CEO of The King Center. "It's the right time, and Martin is in the right place to take this great organization forward," Dexter King said in a statement. Bernice King said she is "proud that my brothers and I are speaking with one voice to communicate our parents' legacy to the world". Martin King added, "We are definitely working together. My brother and sister and I are constantly in communication. ... It's a great time for us."[38] As president of The King Center, King has been credited with spearheading an innovative "King Center Imaging Project" in partnership with JPMorgan Chase, which is digitizing and photographing an estimated 200,000 historic documents, including his father's speeches, sermons, correspondence and other writings and making the documents available on-line to the world.[39] In addition, King launched "The King Center Audio and Visual Digitization Project" in partnership with Syracuse University which will "preserve and digitize some 3,500 hours of audio and video footage" of his father.[40] He has also developed a $100 million renovation plan to upgrade The King Center's Freedom Hall Complex, the first major improvement in the center's site and facilities in its 30-year history.[41]

Along with Reverend Al Sharpton and a number of other civil rights leaders, on August 28, 2010, King took part in the 'Reclaim the Dream' commemorative march, marking the 47th anniversary of the historic Great March on Washington. They spoke at Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C. followed by a reassemblage at the site of the future Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial location in the center of the National Mall. The event coincided with Glenn Beck's Restoring Honor rally planned for the same day on the eastern part of the Mall.[42] King wrote a Washington Post op-ed column offering measured criticism of Beck's event:

While it is commendable that [Glenn Beck's] rally will honor the brave men and women of our armed forces ... [its] organizers present this event as also honoring the ideals and contributions of Martin Luther King Jr. ... My father ... would be the first to say that those participating in Beck's rally have the right to express their views. But his dream rejected hateful rhetoric and all forms of bigotry or discrimination, whether directed at race, faith, nationality, sexual orientation or political beliefs. ... Throughout his life he advocated compassion for the poor. ... Profoundly religious ... my father did not claim to have an exclusionary "plan" that laid out God's word for only one group or ideology. ... I pray that all Americans will embrace the challenge of social justice and the unifying spirit that my father shared with his compatriots.[43]

On April 4, 2011, the 43rd anniversary of the assassination of his father, King helped to lead nationwide demonstrations against initiatives to eliminate and undermine collective bargaining rights of public workers in Wisconsin and other states. King led a mass march in Atlanta and spoke to a crowd of supporters at the Georgia state capitol, urging them to "defend the collective bargaining rights of teachers, bus drivers, police, firefighters and other public service workers, who educate, protect and serve our children and families". On November 17, 2011, King and AFL–CIO President Richard Trumka co-authored an article for CNN, calling for reforms to end oppressive immigration laws.[44]

In August 2013, King went to Philadelphia, where he joined Mayor Michael Nutter in announcing the city's joining of a national campaign on poverty, jobs and education.[45] To commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington, King traveled to Washington, along with other civil rights leaders.[46] On November 21, 2013, King spoke at DePauw University regarding his memories of John F. Kennedy's assassination.[47]

King appeared on MSNBC's The Cycle on May 9, 2014. He was asked by co-host Touré if he believed that Democratic Party has done enough to get the overwhelming support from African Americans it receives. King's answer is said to have shocked the host. "The party does not do enough," he said. "It's our responsibility to hold the party accountable. And I'm not sure we do that. I think we have to find a way to hold the parties accountable." He went on to say that he believed there should be communication between African Americans and the Tea Party Movement, saying "the only way you change is you have to be at least communicating".[48]

Ferguson, Missouri

[edit]In August 2014, King addressed the shooting of Michael Brown and reported that he would come to Ferguson, Missouri.[49] King was present at a rally with Michael Brown's parents on August 17.[50] On an interview with Fox News, King said his father would be "greatly disappointed" with the violence that occurred in Ferguson after the grand jury verdict.[51] King attended Brown's funeral on August 25.[52]

Other pursuits and interests

[edit]In January 2011, it was reported that King would attempt to become a "strategic partner" with the New York Mets baseball team. "This was blown up way out of proportion," King told the Associated Press. "While I'm not leading a group and I'm not having direct conversations ... I think it is very important to promote diversity in ownership."[53] King was among the co-founders of Bounce TV, a black-oriented digital broadcasting network. He currently serves on the Board of Advisors of Let America Vote, an organization founded by former Missouri Secretary of State Jason Kander that aims to end voter suppression.[54]

On February 14, 2021, King attended and spoke at the commemoration of the 190th anniversary of the death of former Mexican president Vicente Guerrero in Cuilapan de Guerrero in Guerrero State, at the invitation of Mexican president Andrés Manuel López Obrador.[55] King also visited the Martin Luther King Jr. statue located in Parque Lincoln, Mexico City.

Ministers March for Justice

[edit]On August 28, 2017, King marched with Al Sharpton in Washington D.C. for the Ministers March for Justice leading over 3,000 ministers to protest the policies of President Donald Trump. King was under major controversy when he agreed to meet with Trump in January 2017.[56]

2021 New York City mayoral election

[edit]On Martin Luther King Jr. Day January 18, 2021, a video was released in which King announced his endorsement of New York City mayoral candidate Andrew Yang, praising Yang's plan to provide a guaranteed minimum income like King's father had wanted and declaring that he was joining the campaign as a co-chair.[57]

Realizing the Dream

[edit]On January 15, 2024, Martin Luther King's 95th birthday, the National Football League announced a five-year commitment to Realizing the Dream, a partnership between the Martin Luther King III Foundation and a charity founded by Marc Kielburger and Craig Kielburger called Legacy+, in which the NFL said that all of its teams would be participating. The initiative calls youth, teachers and communities across the United States and the world to perform 100 million hours of community service by Martin Luther King's 100th birthday in 2029.[58]

That night, Martin Luther King III appeared at Tampa's Raymond James Stadium for the NFC Wild Card Game, where he and his family stood at midfield for the pregame coin toss. Before the coin toss, King III was interviewed about the project, with Tampa mayor Jane Castor and former mayor Pam Iorio in attendance, where he said, "Certainly (the elder King) wanted to eradicate what he defined were the triple evils: poverty, racism and violence. But he also believed in civility and being together, and we could disagree without being disagreeable. Unfortunately, our nation is at a divided point. That’s sort of why football games and championships are so important, because they bring people together, from every walk of life."[59]

Several weeks later, on February 5, the Cincinnati Reds announced that it, too, had joined the Realizing the Dream initiative, with King III appearing at the Cincinnati's Great American Ball Park for the occasion.[60]

King III and his wife Arndrea Waters King wrote a book with Craig and Marc Kielburger titled What Is My Legacy?: Realizing a New Dream of Connection, Love and Fulfillment. Contributors to the book include the Dalai Lama, Julia Roberts, Yara Shahidi, Jay Shetty, Al Sharpton and Sanjay Gupta. The book is scheduled for release on January 14, 2025, the day before what would have been Martin Luther King Jr.'s 96th birthday. Excerpts from the book were republished in People magazine.[61]

Family

[edit]

In May 2006, Martin Luther King III married his longtime partner, Arndrea Waters.[62][63] On May 25, 2008, the couple had a daughter, Yolanda Renee King, the first and only grandchild of Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King.[62] She was named after her aunt, Yolanda King, who had died of a heart condition at age 51 in Santa Monica, California, the previous year.[62] At age 9, Yolanda Renee King spoke at the March for Our Lives demonstration in Washington, D.C. on March 24, 2018.[64][65][66]

Honors and awards

[edit]On February 5, 2006, King, accompanied by the nieces and nephews of Rosa Parks, presented the ceremonial coin at Super Bowl XL. After Super Bowl X MVP and then-ABC Sportscaster Lynn Swann called the toss on behalf of the captains of his former Pittsburgh Steelers teammates and the Seattle Seahawks, the coin was then tossed by New England Patriots quarterback Tom Brady to end the pregame ceremonies, which included a dedication and moment of silence to the memories of Parks and Scott-King and a performance of the Star-Spangled Banner by Dr. John, Aaron Neville and Aretha Franklin accompanied by the Alabama State and Clark Atlanta University choirs.

On March 29, 2008, King threw out the first pitch at the Major League Baseball Civil Rights Game.

On September 19, 2010, King received the Ramakrishna Bajaj Memorial Global Award for outstanding contributions to the promotion of human rights at the 26th Anniversary Global Awards of the Priyadarshni Academy in Mumbai, India.[67]

On September 29, 2015, King was awarded the Humanitarian Award by the Montreal Black Film Festival.[68]

References

[edit]- ^ Company, Johnson Publishing (February 20, 2006). Jet. Johnson Publishing Company.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b c d Gettleman, Jeffrey (August 5, 2001). "M.L. King III: Father's path hard to follow". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 14, 2008.

- ^ Manheimer, p. 46.

- ^ Bagley, p. 148.

- ^ "Martin Luther King III – A Famous Father's Advice to Parents on Bullying". Vancouver Sun. October 14, 2013. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ "King's Kids Assured Education by Belafonte". Jet. April 18, 1968.

- ^ Chu, Louise (January 16, 2005). "Coretta Scott King was the victim of multiple burglaries, son says". Newspapers.com. The Macon Telegraph. Retrieved March 31, 2024.

Coretta Scott King, 77, lived in the family home she bought with her late husband since 1965... The house in southwest Atlanta's Vine City neighborhood...

- ^ Miller, Laurel E. (June 27, 1985). "Coretta King Arrested at Embassy". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011.

- ^ "Children Of King Arrested". Chicago Tribune News. January 8, 1986.

- ^ "Martin Luther King III to Run for Local Office". Los Angeles Times. June 10, 1986.

- ^ "King, Martin Luther, III". June 12, 2017.

- ^ "Our Campaigns - Fulton County Commission 01 - Special Election Race - Nov 02, 1993". www.ourcampaigns.com.

- ^ "Skandalakis shocks King". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. November 3, 1993. p. A1. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- ^ Duffy, Hazel (1995). Competitive cities: succeeding in the global economy. Taylor & Francis. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-419-19840-6.

- ^ Smothers, Ronald (October 30, 1993). "Seeking Identity Beyond 'King's Son'". The New York Times.

- ^ Johnson, Dave (April 16, 1989). "King and Kennedy refuse Death Penalty". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c Fausset, Richard; Jarvie, Jenny (July 12, 2008). "Children of Martin Luther King Jr. embroiled in lawsuit". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ^ "Martin Luther King III Says Bodyguard Saved Mother From 'Crazy Man'". Jet. September 26, 1988.

- ^ Lakshmi, Rama (February 18, 2009). "Son Marks Martin Luther King's 1959 Visit to India". The Washington Post.

- ^ King, Michael (November 15, 2019). "Martin Luther King III joins chorus of voice seeking clemcy for Rodney Reed". WXIA-TV.

- ^ Reding, Shawna (November 15, 2019). "Martin Luther King III sends letter asking Gov. Abbott to stop Rodney Reed's execution". KVUE.

- ^ Associated Press. "Martin Luther King Jr.'s Son Asks Alabama to Stop Inmate's Upcoming Execution". Time Magazine. Archived from the original on March 5, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ Morning Joe. "Martin Luther King III pushes to halt Nathaniel Woods' execution". MSNBC. Retrieved March 15, 2020.

- ^ a b Rodgers, Jacob. "DNC: Martin Luther King III speaks on historic anniversary." Fort Collins Weekly, August 28, 2008. Retrieved on August 28, 2008.

- ^ "Tonight we witness what has become of his dream..." Archived December 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine New England Cable News, August 28, 2008. Retrieved on August 28, 2008.

- ^ Branigin, William; Rucker, Philip (January 20, 2009). "Obama Commemorates MLK Day with Service". The Washington Post.

- ^ Turner, Trish; Katherine Faulders, John Parkinson, Allison Pecorin and Stephanie Ebbs (February 4, 2020). "Trump impeachment trial: Closing arguments ahead of acquittal vote Wednesday". ABC News. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Budryk, Zack (February 4, 2020). "Martin Luther King III blasts Starr's use of King quote in impeachment trial". The Hill. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ King III, Martin Luther (February 4, 2020). "A STATEMENT FROM MARTIN LUTHER KING III ON KEN STARR'S INAPPROPRIATE REFERENCE OF MLK IN DEFENSE OF TRUMP". Twitter.com. Retrieved February 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Firestone, David (July 26, 2001). "A civil rights group suspends, then reinstates, its president". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ^ "Dick Gregory and Martin Luther King III Urge Black Men to Get Tested For Prostate Cancer". Jet. January 17, 2000.

- ^ "Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.'s Family Commemorate 32nd Anniversary Of His Death". Jet. April 24, 2000.

- ^ Suggs, Ernie (August 6, 2001). "Many in SCLC Rally Behind King". The Atlanta Constitution.

- ^ Booth, Georgina Lara Booth (April 20, 2021). "I HAVE A DREAM: Interview with Martin Luther King III, Arndrea King and 12-year-old Yolanda Renee King on Family, Love, Activism and their Dreams by Georgina Lara Booth". Mashable. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- ^ Waldron, Clarence (April 21, 2008). "King Remembered in Memphis 40 Years After Assassination". Jet.

- ^ a b c d Keefe, Bob (August 19, 2008), "King family lawsuit called 'disheartening'", The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Haines, Errin (October 19, 2008). "AP Exclusive: MLK siblings try to justify suit". Associated Press.

- ^ Chen, Eve (April 7, 2010). "King Siblings Reconcile; Martin Luther King III to Head Center Again". WXIA-TV. Archived from the original on July 22, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ Eversley, Melanie (January 16, 2012), "Martin Luther King Papers Go Online", USA Today.

- ^ McDowell, Scott. "Syracuse University and The King Center announce The King Center Audio and Visual Digitization Project", Inside Syracuse University. November 16, 2011.

- ^ Saporta, Maria (January 14, 2012). "MLK III's $100 million plan to upgrade the King Center". Atlanta Business Chronicle. SaportaReport.com. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ Keefe, Bob; Schneider, Craig (August 27, 2010). "Conservatively speaking, thousands will crowd the National Mall". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ King, Martin Luther III (August 25, 2010). "Still striving for Milk's dream in the 21st century". Washington Post.

- ^ King, Martin Luther III; Trumka, Richard (November 17, 2011). "Alabama's immigration law: Jim Crow revisited". CNN.

- ^ Gregg, Cherri (August 7, 2013). "Eldest Son of Dr. MLK Visits Philadelphia As 'I Have a Dream' Anniversary Draws Near". CBS Philly.

- ^ Rabouin, Dion (December 26, 2013). "Atlanta Daily World Looks Back at the Top Stories of 2013". Atlanta Daily World.

- ^ Wang, Stephanie (November 21, 2013). "DePauw University welcomes Martin Luther King III". IndyStar.

- ^ Quinn, Melissa (May 10, 2014). "MLK III shocks Touré: African-Americans should be engaged with the Tea Party". Red Alert Politics.

- ^ "Martin Luther King III speaks on Ferguson shooting, violence". KSDK.com. August 13, 2014.

- ^ Kiekow, Anthony (August 17, 2014). "Rev. Al Sharpton and Martin Luther King III lead rally for Brown family". FOX2now.com.

- ^ "Martin Luther King III: My Father Would Be 'Greatly Disappointed' in Ferguson Violence". Fox. November 26, 2014. Archived from the original on February 20, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2014.

- ^ "At Michael Brown's funeral, a call for social change". CNN. August 25, 2014.

- ^ "Report: King's son interested in buying into Mets". Yahoo! Sports. Associated Press. January 31, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Advisors". Let America Vote. Retrieved May 1, 2018.

- ^ Exteriores, Secretaría de Relaciones. "Martin Luther King III in Mexico to commemorate the anniversary of the death of Vicente Guerrero". gob.mx (in Spanish). Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "Clergy march for racial justice on anniversary of Martin Luther King's 'I Have a Dream' speech". USA Today. August 28, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ "Martin Luther King III endorses Andrew Yang for Mayor of New York City". YouTube.

- ^ Knight, Joey (January 15, 2024). "Family of Martin Luther King Jr. aligns with NFL to carry on 'dream'". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Knight, Joey (January 15, 2024). "Family of Martin Luther King Jr. aligns with NFL to carry on 'dream'". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Martin, Alexis (February 5, 2024). "Reds announce 'Realizing the Dream' initiative with Martin Luther King family". WXIX-TV. Retrieved February 9, 2024.

- ^ Schumer, Lizz (November 12, 2024). "What Is My Legacy? Martin Luther King III's New Book Offers a Path to Fulfillment". People.

- ^ a b c Zimmerman, Karl; et al. (May 26, 2008), "First MLK grandchild born", CNN, archived from the original on June 4, 2008, retrieved May 26, 2008,

The girl carries the first name of her father's sister, the oldest of the four King children, who died last year.

- ^ Suggs, Ernie (April 3, 2018), "Role as husband, father charts course for King family", The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, archived from the original on January 18, 2021, retrieved October 1, 2021,

The former Arndrea Waters stuck around and years later found herself part of the King family.

- ^ Carissimo, Justin; Craver, Thom (March 24, 2018), "March for Our Lives 2018 -- live blog", CBS News website, archived from the original on March 27, 2018, retrieved January 7, 2019

- ^ "Bernice King on the 50 years since her father's death: 'This nation is awoke'". The Guardian. London. April 2, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ "MLK Jr.'s granddaughter surprises rally crowd - CNN Video". CNN. March 24, 2018. Retrieved October 10, 2018.

- ^ "Recipients of Global Awards 2010". Priyadarshni Academy. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

- ^ "Martin Luther King III receives Humanitarian Award". CTV Montreal News. September 30, 2015.

Works cited

[edit]- Manheimer, Ann S. (2004). Martin Luther King Jr: Dreaming of Equality. Carolrhoda Books. ISBN 978-1-57505-627-2.

- Bagley, Edythe Scott (2012). Desert Rose: The Life and Legacy of Coretta Scott King. University Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1765-2.

External links

[edit]- 1957 births

- Living people

- 20th-century Baptists

- 21st-century Baptists

- Activists for African-American civil rights

- African-American Christians

- Alabama Democrats

- Baptists from Alabama

- Baptists from Georgia (U.S. state)

- Fulton County commissioners

- Georgia (U.S. state) Democrats

- Family of Martin Luther King Jr.

- Morehouse College alumni

- Activists from Montgomery, Alabama