Mark Emmert

Mark Emmert | |

|---|---|

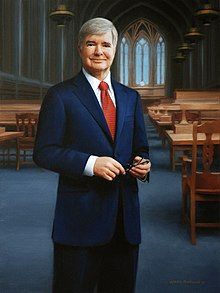

Emmert in February 2014 | |

| 5th President of the National Collegiate Athletic Association | |

| In office November 1, 2010 – March 1, 2023 | |

| Preceded by | Myles Brand |

| Succeeded by | Charlie Baker |

| 30th President of the University of Washington | |

| In office June 2004 – October 1, 2010 | |

| Preceded by | Lee L. Huntsman |

| Succeeded by | Michael K. Young |

| Chancellor of Louisiana State University | |

| In office 1999–2004 | |

| Preceded by | Williams L. Jenkins |

| Succeeded by | William L. Jenkins (interim) Sean O'Keefe |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mark Allen Emmert[1] December 16, 1952 Fife, Washington, U.S. |

| Spouse | DeLaine Emmert |

| Alma mater | University of Washington (BA) Syracuse University (MPA, PhD) |

| Profession | Academic administrator |

| Academic background | |

| Thesis | Coevolutionary theory and organizational commitment: An exploratory study in bureaucratic behavior (1983) |

| Academic work | |

| Discipline | government and political studies |

| Institutions | |

Mark Allen Emmert (born December 16, 1952) is the former president of the National Collegiate Athletic Association. He was the fifth CEO of the NCAA; he was named as the incoming president on April 27, 2010, and assumed his duties on November 1, 2010, and remained in office until March 1, 2023.

Emmert was previously the 30th president of the University of Washington, his alma mater, taking office in June 2004, becoming the first alumnus in 48 years to lead UW. He left Washington on October 1, 2010, having announced his departure for the NCAA Presidency on April 27, 2010. The University of Washington Board of Regents elected him President Emeritus in honor of his service to the UW.

Before Emmert became president of the University of Washington, he was chancellor at Louisiana State University and held faculty and administration positions at the University of Connecticut, Montana State University, and University of Colorado.

Early life and education

[edit]Emmert was born on December 16, 1952, in Fife, Washington and attended Fife High School, graduating in 1971. He studied at Green River Community College in Auburn, Washington before transferring in spring 1973 to the University of Washington, where he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in 1975.[1] He went on to earn a Master of Public Administration in 1976 and a PhD in 1983 from the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs of Syracuse University.[2][3]

Career

[edit]Northern Illinois University

[edit]Non-tenured positions (Research Associate, Asst. Professor) in government and political studies 1983-85.[4]

University of Colorado Boulder

[edit]Emmert had various academic administrative positions at the University of Colorado Boulder (1985-92).[5] He has listed these on his C.V.: appointments in the Graduate School of Public Affairs as Associate/Assistant Professor, and Associate Dean responsible for daily administration of academic and student matters; Assistant to the UC System president, and an Associate Vice-Chancellor. Emmert was a Fellow of the American Council on Education.[6]

Montana State University

[edit]Emmert served as provost and vice president for academic affairs at Montana State University from 1991 to 1995. In this role, he, along with the vice president for research, Robert Swenson, led a successful effort to increase research funding at the university, including from the National Science Foundation. He also worked with U.S. Congressional leaders to gain support for new agricultural research facilities on campus and distance learning programs.

The NCAA ruled that Montana State was guilty of a "lack of institutional control" in 1993, stemming from behavior that occurred before Emmert arrived at the university. The ruling was reached at the time Emmert belonged to the university's senior management team, along with Jim Isch, a former NCAA official. The case related to academic fraud involving an assistant men's basketball coach and a recruit. The NCAA didn't rule on the case until after Emmert left for UConn in 1995. Emmert had no involvement with the athletic programs in his role as provost and was unaware of the investigation, nor was he ever named or implicated in any wrongdoing.[7]

University of Connecticut

[edit]Emmert joined the University of Connecticut in 1995 as Provost and was later promoted to the position of chancellor for academic affairs, where he oversaw academic matters at the main campus in Storrs, as well as the regional campuses within the university system. He led a strategic planning effort that produced a facilities master plan for the Storrs campus, transforming the facilities on the campus with new buildings for students, faculty and research. Enrollment and research funding both increased during this time. During his tenure the university launched its first major fundraising campaign.

Emmert oversaw the first two years of a ten-year-long, $1 billion construction project, UConn 2000, that added many new academic buildings, residence halls and landscape projects to the Storrs campus, and new buildings and facilities to the regional campuses. UConn 2000 is widely credited with transforming the university. Some of the projects became controversial because of charges of mismanagement in the facilities and contracting services. These issues, which included more than $100 million lost due to mismanagement and more than a hundred fire and safety code violations, did not come to light during Emmert's tenure. The vast majority of the projects were begun after Emmert's tenure. Something handwritten on Emmert's stationery in 1998 suggested he was aware of construction management challenges. Some of the construction projects later became the focus of a state investigation in 2005. Governor Rell called it "astonishing failure of oversight and management." Two administrators who oversaw the projects during this time were placed on leave and subsequently resigned six years after Emmert had left the university.[7]

Louisiana State University

[edit]Emmert was named Chancellor of Louisiana State University in 1999. He led the creation of the "Flagship Agenda," an effort credited with moving the university significantly forward in its standing as an academic institution, an effort that is still credited with advancing the university in very significant ways. During his tenure the academic preparation of entering freshmen increased substantially. Enrollment from across the country increased as well. LSU's research profile improved as a result of new research initiatives, particularly in computer science, marine and coastal science, and basic sciences. A number of academic construction projects commenced, including buildings and renovations for music and dramatic arts, marine biology and coastal studies, biology, residence halls, and the student union. Fund raising projects were begun that have resulted in dramatic improvements in the Ogden Honors College, the E.J. Ourso College of Business and the College of Engineering. Improvements were made to athletic facilities, most notably the creation of the Cox Communications Academic Center, renovation and expansion of Tiger Stadium, and a new state-of-the-art enclosure for the campus mascot, Mike the Tiger, that has become a major attraction for visitors to campus. Emmert’s wife, DeLaine Emmert, was very engaged in these fund raising efforts. State support for the university reached a then-historic high during Emmert's tenure.

On November 30, 1999, Emmert hired Nick Saban as football coach. LSU won the BCS Championship in 2003 under Saban's tutelage and was 48-16 over five seasons (2000–04). Prior to Saban's arrival, LSU suffered eight losing seasons from 1989-99.

The graduation rate of the LSU football team, among the lowest in the SEC when Emmert arrived, was among the highest by 2004.

In 2001–02, a university instructor made accusations of academic fraud in the school's football program, including plagiarized papers and un-enrolled students showing up in class to take notes for football players. At the time, LSU was already on NCAA probation due to violations in the men's basketball program for violations that predated Emmert's employment. A university-led investigation into the academic fraud allegations found only minor violations. The report stated, "Despite isolated incidents, the allegations were largely unfounded." The NCAA accepted LSU's finding and self-imposed minor penalties (loss of two football scholarships) and declined to put the school on probation. Subsequently, two women sued the university for forcing them from their jobs as a result of whistleblowing about the academic fraud. The lawsuits were settled for $110,000 for each person. During the case, an employee of the academic counseling center confirmed the women's claims under oath, including changed grades for football players. A portion of Emmert's salary was paid by the LSU Foundation, The Alumni Foundation and the Tiger Athletic Foundation.[7]

In September 2016 Emmert was honored by LSU as the first Haymon Distinguished Visiting Professor at the Ogden Honors College. In 2020, he was named a faculty/staff initiate of the Omicron Delta Kappa Circle at LSU.

University of Washington

[edit]Emmert was president of the University of Washington, his alma mater, from 2004 to 2010. During his tenure the university achieved its highest levels of research funding, private giving, and state support. Undergraduate student qualifications and graduation rates also hit record highs. UW attracted more students globally and nationally. Emmert led the creation of the Husky Promise, a guarantee that tuition and fees would be covered for lower-income students from Washington state who were accepted to UW, a program that has now supported tens of thousands of students at the UW. The UW also increased access for Washington students by expanding UW Bothell and UW Tacoma academic offerings and facilities during Emmert's tenure. The UW Seattle campus was expanded with the purchase of the Safeco tower and property in the University District, adding about 500,000 square feet (46,000 m2) of building space. With Emmert as President, new facilities were created for the Foster School of Business, molecular engineering, bioengineering, and residential halls. Improvements were made to athletic facilities, culminating in the full renovation of Husky Stadium.

Emmert initiated an annual summit with the Native American tribal council leaders from throughout the State of Washington and the region to address educational and health concerns. He led the process that culminated in the construction of a Native American House of Knowledge on campus. UW has been attentive to environmental and sustainability issues, and received numerous recognitions for its success during Emmert's tenure. Emmert was amongst the first 20 to sign the American College & University Presidents' Climate Commitment and is an active member of its steering committee.[8]

During Emmert's tenure, UW received more than $1 billion in grant and contract research funding for the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2007. This marked the first time UW received more than $1 billion in funding for sponsored research in a single year. In his last year at UW, research funding exceeding $1.5 billion. UW has been the top public university in federal research funding since 1974, and among the top five universities, public and private, in federal funding since 1969. In recent years, it has been second only to Johns Hopkins University. In 2006, under Emmert's presidency, the university created the Department of Global Health and, in the spring of 2007, launched the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. In August 2007, Emmert announced that UW would open an office in Beijing to lay the groundwork for expanding the university's presence in China.[9] Emmert made the announcement during a campus visit by Zhou Wenzhong, ambassador of the People's Republic of China to the United States.

Emmert emphasized efforts to improve UW's environmental sustainability efforts throughout his tenure, leading to the university being recognized nationally as one of the most Eco-friendly campuses

In January 2007, the fundraising goal for Campaign UW: Creating Futures was increased to $2.5 billion after the campaign reached its initial $2 billion goal 17 months ahead of schedule.[10] When the campaign ended on June 30, 2008, the total raised was more than $2.6 billion.[11] UW received a number of transformational gifts during Emmert's presidency, including a gift in fall of 2007 from the Foster Family Foundation, leading to the business school at the Seattle campus being named the Michael G. Foster School of Business. Emmert was president at the University of Washington when the university announced it was discontinuing its varsity men's and women's swim programs.

While at the University of Washington, Emmert was courted by the University of Wisconsin, the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, Cornell University, the University of California System, and the Louisiana State University System. In February 2008, he turned down an offer from Vanderbilt University that might have made him the highest-paid college leader in the nation.[12] Nevertheless, he was the second most highly compensated public university president in the nation, at $888,000 for 2007-2008.[13] In addition, he received $200,000 compensation for serving on the board of Expeditors International and $140,000 for serving on the board of Weyerhaeuser, giving him a total annual compensation of over $1.2 million.[14] In 2009, a year in which he turned down a pay increase offered by the Regents, Emmert's base salary at the University of Washington was $620,000 per year, but his total compensation package, including deferred compensation, was $906,500 annually, which made him the second highest-earning public university president in the United States, behind Ohio State's Gordon Gee.[15]

National Collegiate Athletic Association

[edit]

On April 27, 2010, Emmert was named president of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, headquartered in Indianapolis. He assumed his duties on November 1, 2010, and remained president until his retirement in March 2023.

As NCAA president, Emmert created the position of chief medical officer (CMO) of the NCAA and the Sports Science Institute. Hainline has worked with member schools to establish new protocols and research efforts to improve student health and wellness. In 2014, the NCAA entered a partnership with the Department of Defense for the largest longitudinal study of concussion and head trauma in history, funded initially by a $15 million contribution from the NCAA and $15 million from the Department of Defense. Funding has now surpassed $64 million and reached 50,000 students making it by far the most important research on head trauma in the world. Emmert’s advocacy for the health and wellbeing of athletes has also led to extensive efforts regarding mental health and the reduction of sexual assault.

In 2014, the NCAA Division I member universities, with Emmert's support, voted to change the system used to set their rules and policies so as to include greater input from athletic directors, faculty members, and senior women's athletics, and student athletes themselves, in addition to the university and college presidents who are ultimately responsible for all policy and governance decisions. In 2012 the colleges and universities approved substantial changes to the compliance and oversight policies of the Association. Among other improvements, under Emmert's tenure, the Committee on Infractions, the body that determines penalties and sanctions for rules violations, was expanded to include former university presidents and legal scholars, among others, thereby improving the efficiency and effectiveness of their work.

In January 2018, a misleading media story implied that Emmert had been personally informed in November 2010 – six months after he was hired as the NCAA's president – of 37 reports involving Michigan State University athletes sexually assaulting women.[16] Subsequent reporting in multiple outlets pointed out that the suggestion that Emmert had been "personally informed" was actually a misleading reference to widely publicized accounts coming from Michigan State during 2010. Throughout his tenure, Emmert has led multiple efforts within the NCAA to confront sexual violence within higher education.[citation needed]

On April 26, 2022, Emmert announced he would step down no later than June 2023.[17] That December, Former Massachusetts governor Charlie Baker was announced as Emmert's successor effective March 1, 2023.[18]

Penn State case

[edit]During Emmert's tenure, Pennsylvania State University was rocked by the Jerry Sandusky sex abuse scandal. Sandusky, a former assistant football coach at Penn State, was accused and later convicted of sexually abusing several children, including those he had taken to the Penn State athletic facilities. He was also accused of using his access to the Penn State football program as a way of luring victims. The University Board removed the President, Executive Vice President, Athletic Director, and head football coach because of their handling of the Sandusky matter. The media outcry over the scandal was enormous. In response to the uniqueness of the Penn State case and the nature of the allegations, the NCAA Executive Committee and Emmert agreed with the University that Penn State should be allowed to conduct its own inquiry into the scandal.

In July 2012, former FBI Director Louis Freeh reported to the Penn State board that many serious missteps within the university administration and football program had occurred. Based upon the Freeh report, as well as material made public through the criminal processes, the NCAA Executive Committee, a group of 20 university and college presidents and senior leaders, along with the Division I Board of Directors, also a group of university presidents, agreed to a series of sanctions. They empowered Emmert to enter into an agreement with the Penn State leadership to jointly accept a consent decree.

Ed Ray, Executive Committee chair at that time and Oregon State president, said that while there has been much speculation on whether the NCAA[19] had the authority to impose any type of penalty related to Penn State, the Executive Committee concluded that the egregious behavior not only goes against the NCAA's rules and constitution, but also against its values.

While many in the media called for Penn State football to receive the so-called "death penalty", the Executive Committee and Emmert instead entered into the consent decree with Penn State leadership that included imposing a $60 million fine to be used to fund nonprofit organizations that combat child sexual abuse, a multi-year reduction in football scholarships, a multi-year postseason ban on football, a vacation of wins from the formal record book for the period during which Sandusky was believed to have been engaging in sexual abuse of children, and the imposition of an Athletic Integrity Agreement, which was monitored by former Senator George J. Mitchell. The Big Ten conference, which includes Penn State as a member, also imposed sanctions on the university as a result of the scandal. The outcome was highly controversial among those who sought harsher punishment and those who sought greater leniency. Supporters of greater leniency argued that the basis of the consent decree, the Freeh Report, was overreaching and not supported empirically.[20][21] Freeh has vigorously defended the report and its conclusions. He is being sued for defamation by Graham Spanier, the former president of Penn State.[22] Spanier, along with two other former Penn State executives, were found guilty of criminal charges. Critics accused Emmert and the NCAA Executive Committee of a "rush to judgment" that did not provide sufficient due process even though the university itself agreed to the settlement agreement.[23]

Emmert, however, was criticized over the Penn State case after internal emails surfaced revealing NCAA officials bluffed the university into accepting sanctions.[24]

Several legal actions have occurred since the Penn State scandal was uncovered, some involving Penn State, Emmert, and the NCAA and its members; others have been focused on the university itself as it made restitution with the victims of the scandal. A legal suit was brought against Penn State and the NCAA by Pennsylvania Senator Jake Corman regarding where the funds from the fine should be spent.[25] The case was ultimately settled by an agreement that the funds could be spent on child sexual abuse prevention within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania and that the wins that had been vacated from the record book be restored. Major news media outlets both praised and criticized Emmert and the NCAA. Many writers that called for aggressive sanctions against the university, including the so-called death penalty, were disappointed that the NCAA had reduced its sanctions, while other were critical of their "rush to judgment" and started asking whether the culture at the NCAA was broken under Emmert's leadership.[26] His presidency has been called "feckless, arrogant, self-aggrandizing, inept" and operating under "tortured logic."[27]

Final resolution of Penn State-Sandusky scandal

[edit]On May 5, 2016, a Pennsylvania judge, Gary Glazer, barred Penn State from receiving insurance coverage to pay settlements to Sandusky's accusers. The judge pointed to the university's "negligent employment, investigation, and retention of Sandusky", adding that, "When he abused children...he was still a PSU assistant coach and professor, and clothed in the glory associated with those titles, particularly in the eyes of impressionable children. By cloaking him with a title that enabled him to perpetrate his crimes, PSU must assume some responsibility for what he did both on and off campus." PSU at that point had paid out $93 million to more than 30 Sandusky accusers.[28]

On October 27, 2016, Mike McQueary, the former assistant coach who reported to Joe Paterno that he had observed Sandusky sexually assaulting a child in the team's showers, was awarded $7.3 million by a Pennsylvania jury, to be paid by Penn State for defamation. Shortly thereafter on November 20, 2016, the judge in the case, Thomas Gavin, ruled in favor of McQueary's whistleblower claim and added another $5 million to the jury verdict. In a rebuke to PSU, Gavin wrote, "Only when the 'Sandusky Matter' became public was Mr. McQueary subjected to disparate treatment and adverse employment consequences." The university, he stated, had imposed "the equivalent of banishment" on McQueary, including "being told to clean out his office in the presence of Penn State personnel, an action that suggests he had done something wrong and was not to be trusted."[29]

On June 2, 2017, in the remaining criminal cases all three of the university's administrators – Spanier, Schultz, and Curly – originally implicated by the Freeh Report and the grand jury were found guilty of child endangerment by the State of Pennsylvania and sentenced to jail time. The judge in the case, John Boccabella, when announcing the sentences said, "Why Mr. Sandusky was allowed to continue to go to the Penn State facilities is beyond me. All three ignored the opportunity to put an end to [Sandusky's] crimes when they had a chance to do so." Boccabella also criticized deceased head coach Joe Paterno, saying he "could have made that phone call without so much as getting his hands dirty. Why he didn't is beyond me."[30]

Other honors and professional affiliations

[edit]Emmert is currently a Life Member of the Council of Foreign Relations and a fellow of the National Academy for Public Administration. He is a former Fulbright Administrative Fellow, and a former Fellow of the American Council on Education. He serves as a Director on the boards of Weyerhaeuser and Expeditors International. In June 2016, he sold approximately $300,000 in Weyerhaeuser shares. Emmert has been honored with several honorary degrees from American universities and colleges.

Emmert was named President Emeritus by the University of Washington Board of Regents in 2010. He holds honorary degrees from several colleges and universities.

On March 18, 2014, Emmert was a guest on ESPN Radio's Mike & Mike. During his appearance, an #AskEmmert hashtag was used to propose questions for Emmert. While well-intended, the hashtag was quickly used by the public to air grievances about NCAA actions and express general disapproval with Emmert's presidency.[31]

Personal life

[edit]Mark and DeLaine Emmert have been married for more than 40 years and have two adult children.[citation needed]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Griffin, Tom (June 2004). "The homecoming". The University of Washington Alumni Magazine. Retrieved June 13, 2014.

- ^ DiDomenico, Tammy (January 1, 1999). "Alumni Academic Leaders". Syracuse University Magazine. Vol. 16, no. 2. p. 8. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Emmert, Mark Allen (1983). Coevolutionary Theory and Organizational Commitment: An Exploratory Study in Bureaucratic Behavior (PhD). Syracuse University. OCLC 15081138. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ Mark A. Emmert, Curriculum Vitae |http://fs.ncaa.org/Docs/newmedia/public/images/president/MAE.pdf

- ^ Biography|NCAA President Mark Emmert|https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2013/11/25/ncaa-president-mark-emmert.aspx

- ^ Mark A Emmert CV ncaa.org

- ^ a b c Brent Schrotenboer (April 3, 2013). "Digging into the past of NCAA President Mark Emmert". Usatoday.com. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "Home | Presidents' Climate Commitment". Presidentsclimatecommitment.org. November 29, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Valdes, Manuel (August 23, 2007). "UW office to open new doors in China". Seattletimes.com. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Christine Fre (January 26, 2007). "UW reaches its $2 billion goal, then strives for more". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Seattlepi.com. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "About Campaign UW - Campaign UW: Creating Futures - University of Washington Foundation". Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ Perry, Nick; Miletich, Steve (February 28, 2008), "UW's president turns down offer from Vanderbilt", The Seattle Times

- ^ Wiedeman, Reeves (November 21, 2008), "For a Raise, Try Looking in the Evergreen State", Chronicle of Higher Education

- ^ Perry, Nick (November 17, 2008), "UW, WSU presidents among highest paid in country", The Seattle Times, archived from the original on November 13, 2011

- ^ "UW president gets new perks, but no raise". The Seattle Times. September 4, 2009. Retrieved September 4, 2009.

- ^ "NCAA president Mark Emmert was alerted to Michigan State sexual assault reports in 2010". The Athletic. January 26, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "NCAA President Mark Emmert steps down, effective June 2023" (Press release). NCAA. April 26, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "NCAA Announces Governor Charlie Baker to be Next President" (Press release). NCAA. December 15, 2022. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ "NCAA levies sanctions". NCAA. Retrieved December 17, 2012.

- ^ "King & Spalding : Critique of the Freeh Report" (PDF). Espn.go.com. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "usurped title" (PDF). ps4rs.org. Archived from the original on April 28, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help)CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Graham Spanier sues Louis Freeh". Espn.go.com. July 15, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Dodd, Dennis (November 7, 2014). "No bluffing - NCAA has lost all of its credibility with Penn State, USC, etc". CBSSports.com. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Tracy, Marc (November 5, 2014). "N.C.A.A. Questioned Its Authority in Penalizing Penn State". The New York Times.

- ^ Berger, Zach (January 16, 2015). "Paterno's Wins Restored and Consent Decree Replaced in Corman Settlement". Onwardstate.com. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ "Armour: NCAA failed victims in rush to judge Penn State". Usatoday.com. January 16, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Litke, Jim (March 6, 2015). "Column: Maybe Joe will get his statue back, too". Yahoo Sports. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Tracy, Marc (October 27, 2016). The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Tribune news services, Chicago Tribune, November 30, 2016

- ^ Bernstein, Dan (June 3, 2017). "Bernstein: Judge Shames Joe Paterno's Inaction At Penn State". CBS Chicago. Retrieved May 17, 2021.

- ^ "The #AskEmmert Q&A Is Going Poorly". Deadspin.com. April 18, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

External links

[edit]- 1952 births

- Living people

- 2011 University of Miami athletics scandal

- American chief executives

- Green River College alumni

- Leaders of Louisiana State University

- Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs alumni

- National Collegiate Athletic Association people

- Presidents of the University of Washington

- University of Colorado Boulder faculty

- University of Connecticut faculty

- University of Washington alumni