Jan Matejko

Jan Matejko | |

|---|---|

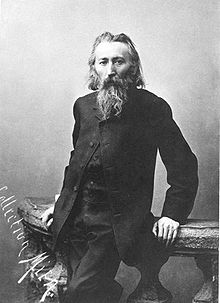

Matejko, before 1883 | |

| Born | Jan Alojzy Matejko 24 June 1838 |

| Died | 1 November 1893 (aged 55) |

| Resting place | Rakowicki Cemetery, Kraków, Poland |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Other names | Jan Mateyko |

| Education | |

| Known for | Painting, drawing, teaching |

| Notable work | |

| Movement | History painting, academic art |

| Spouse | Teodora Giebułtowska |

| Awards | |

Jan Alojzy Matejko (Polish pronunciation: [ˈjan aˈlɔjzɨ maˈtɛjkɔ] ⓘ; also known as Jan Mateyko; 24 June 1838[nb 1] – 1 November 1893) was a Polish painter, a leading 19th-century exponent of history painting, known for depicting nodal events from Polish history.[2][3] His works include large scale oil paintings such as Stańczyk (1862), Rejtan (1866), Union of Lublin (1869), Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God (1873),[4] or Battle of Grunwald (1878). He was the author of numerous portraits, a gallery of Polish monarchs in book form, and murals in St. Mary's Basilica, Kraków. He is considered by many as the most celebrated Polish painter, and sometimes as the "national painter" of Poland.[2][3][5]

Matejko spent most of his life in Kraków. He enrolled at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts at age fourteen, where he studied under notable artists such as Wojciech Korneli Stattler and Władysław Łuszczkiewicz and completed his first major historical painting in 1853. His early exposure to revolutions in Kraków and the military service of his brothers influenced his artistic themes. After studying art in Munich and Vienna, he returned to Kraków and set up a studio. He gradually gained recognition, selling key paintings that settled his debts and created some of his most famous works, including Stańczyk and Skarga's Sermon. Matejko's art played a key role in promoting Polish history and national identity at a time when Poland was partitioned and lacked political autonomy.

At the same time, Matejko's painting style has been criticised as old-fashioned and overly theatrical, labeled as "antiquarian realism". His works often lost their nuanced historical significance when displayed abroad due to the audience's unfamiliarity with Polish history. Matejko's support for the Polish cause was not just through his art; he also contributed financially and materially to the January Uprising of 1863. Later, he became director of the art academy in Kraków, which was eventually renamed the Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts. A number of his students became prominent artists in their own right, including Maurycy Gottlieb, Jacek Malczewski, Józef Mehoffer and Stanisław Wyspiański. He received several honors during his lifetime, including the French Légion d'honneur. Matejko was among the notable people to receive an unsolicited letter from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, as the latter tipped, in January 1889, into his psychotic breakdown while in Turin.[6][7]

Biography

[edit]Youth

[edit]Matejko was born on 24 June 1838, in the Free City of Kraków.[2] His father, Franciszek Ksawery Matejko (Czech: František Xaver Matějka) (born 1789 or 13 January 1793, died 26 October 1860), a Czech from the village of Roudnice, was a graduate of the Hradec Králové school who later became a tutor and music teacher.[2] He first worked for the Wodzicki family in Kościelniki, Poland, then moved to Kraków, where he married the half-German, half-Polish Joanna Karolina Rossberg (Rozberg).[2] Jan was the ninth of eleven children. His mother died when he was very young and his older brother, Franciszek had a hand in the manner of his upbringing.[8] He grew up in a kamienica building on Floriańska Street.[9] After the death of his mother in 1845, Jan and his siblings were cared for by his maternal aunt, Anna Zamojska.[8]

At a young age he witnessed the Kraków revolution of 1846 and the 1848 siege of Kraków by the Austrians, two events which put an end to the Free City of Kraków.[2] Two of his older brothers served in both armed conflicts, under General Józef Bem. One of them, Edmund, fell in battle and the other was forced into exile.[2] Matejko attended St. Anne's High School, but he dropped out in 1851 because of poor grades. Matejko showed an early artistic talent, but had great difficulty with other academic subjects.[10] He never fully mastered a foreign language.[11] Despite that, and because of his exceptional skill, at the age of fourteen he entered the School of Fine Arts in Kraków, where he was a contemporary of Artur Grottger from 1852 to 1858.[2] His teachers included Wojciech Korneli Stattler and Władysław Łuszczkiewicz.[12] He opted for historical painting as his specialism, and finished his first major work, The Shuyski Tsars before Zygmunt III (Carowie Szujscy przed Zygmuntem III), in 1853 (he would return to this theme a year before his death, in 1892.[13][12][14] During this time, he began exhibiting historical paintings at the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts from 1855.[14] His graduation project in 1858 was Sigismund I the Old ennobles professors of the Jagiellonian University (Zygmunt I nadaje szlachectwo profesorom Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego) and proved to be seminal.[15]

After graduation in 1859,[15] Matejko received a scholarship to study with Hermann Anschütz at the Academy of Fine Arts, Munich.[14] The following year he received a further scholarship to study at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, but after only a few days and a major quarrel with Christian Ruben, Matejko returned to Kraków.[16] He set up a studio at his family home in Floriańska Street.[16] It took years before he met with commercial success. He struggled as the proverbial "starving artist", who finally celebrated when he managed to sell the Shuyski Tsars... canvas for five florins.[2]

In 1860, against a background of cultural erosion in partitioned Poland Matejko published an illustrated album, Clothing in Poland (Ubiory w Polsce), a project reflecting his intense interest in the historical record of his nation and his desire to promote it among Polish people and incidentally stir their patriotism.[16] His financial situation improved when he sold two paintings, The assassination of Wapowski during the coronation of Henri de Valois (Zabicie Wapowskiego w czasie koronacji Henryka Walezego, 1861) and Jan Kochanowski over the body of his daughter Urszulka (Jan Kochanowski nad zwłokami Urszulki, 1862), which settled his debts.[17] 1862 saw the completion of his Stańczyk, initially received without much acclaim, but in due course becoming one of Matejko's best known works.[18] It marks a manifest departure in Matejko's art, from mere illustrator of history to commentator upon its moral content.[16]

During the January Uprising of 1863, in which he did not directly take part on account of his poor health, Matejko supported it financially, donating most of his savings to the cause, and personally transporting arms to an insurgents' camp.[16] Subsequently, his Skarga's Sermon (Kazanie Skargi), May 1864, was exhibited in the gallery of the Kraków Society of Friends of Fine Arts, which gained him much publicity.[16] On 5 November that same year, he was elected member of the Kraków Scientific Society (Towarzystwo Naukowe Krakowskie) in recognition for his contributions to depicting great national historical themes.[19] On 21 November he married Teodora Giebułtowska, with whom he went on to have five children: Beata, Helena, Tadeusz, Jerzy and Regina.[16] His daughter, Helena, also an artist, later helped World War I victims and was awarded the Cross of Independence by President Stanisław Wojciechowski.[20]

Rise to fame

[edit]

]

After 1865 Matejko's international recognition grew. His Skarga's Sermon was awarded a gold medal at the 1865 Paris Salon, prompting Count Maurycy Potocki to buy it for 10,000 florins.[2] In 1867, his painting Rejtan was awarded a gold medal at the World Exhibition in Paris and was acquired by Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria for 50,000 franks.[21][22] His next major painting was the Union of Lublin (Unia Lubelska), created during 1867–1869. Acclaimed in Paris, it won Matejko the Cross of the Légion d'honneur.[23] and was purchased by the Sejm of Galicia.[24] It was followed by Stefan Batory at Pskov (Stefan Batory pod Pskowem), finished in 1871.[23] In 1872, he visited Istanbul and upon his return to Kraków finished The Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God (Astronom Kopernik, czyli rozmowa z Bogiem), which was acquired by the Jagiellonian University.[23] From the 1870s onwards he was aided by a secretary, Marian Gorzkowski, who became his personal assistant, his closest friend, a model for a number of his paintings, and the author of a memoir about Matejko.[24][25]

In 1872, during an exhibition in Prague he was offered the directorship of the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, quickly followed by a similar offer from the Kraków School of Fine Arts.[23] He accepted the Kraków position, and was for many years its principal (rector).[23] In 1874, he finished Zawieszenie dzwonu Zygmunta (The Hanging of the Sigismund bell).[26] In 1878, he produced another masterpiece, The Battle of Grunwald.[24] That year he received an "honorary grand gold" medal in Paris, while Kraków city council presented him with a ceremonial scepter, as a symbol of his "royal status in fine art".[24] In 1879 came his Rok 1863 - Polonia (The Year 1863 - Polonia), his depiction of the January Uprising. Begun in 1864 as the Uprising was waning, he abandoned the canvas for a number of years, perhaps due to the loss of several close friends and family members in the conflict. It languished unfinished until prince Władysław Czartoryski became interested in acquiring it. To this day it is considered unfinished.[16][27][28]

1880-1882 were taken up with another large work, The Prussian Tribute (Hołd Pruski) which Matejko gifted to "the Polish nation". It earned him the honorary citizenship of Kraków.[24] One of the city's squares was renamed Matejko Square.[24] In 1883 he finished Jan Sobieski at Vienna (Jan Sobieski pod Wiedniem) which came to be presented to Pope Leo XIII as a "gift of the Polish nation".[14][24] Being a member of the delegation delivering the canvas to Rome, Matejko was awarded the Knight Commander with Star of the Order of Pius IX.[29] The painting is on permanent exhibition in the Sobieski Room at the Vatican Museums.[30] Around that time he also became vocal on a number of political issues, publishing letters on topics such as Polish-Russian relations.[29] He was also very engaged in efforts to protect and reconstruct historical monuments in Kraków.[31] In 1886, he finished a painting relating to French rather than Polish history, The Virgin of Orléans, a portrayal of Joan of Arc.[29][32]

In 1887 Matejko received an honorary doctorate from the Jagiellonian University, and recognition from the Austrian Society, Litteris et Artibus.[29] In 1888 he completed The Battle of Racławice (Bitwa pod Racławicami).[29] In 1888-1899, to justify his new academic title, he published a group of twelve drawings with accompanying commentary, The History of civilisation in Poland (Dzieje Cywilizacji w Polsce).[26][29] Between 1890 and 1892, he published a series of works on paper, portraying all the monarchs of Poland (Poczet królów i książąt polskich - The kings and princes of Poland, including queens), whose popularity turned them into the canon portrayals of their subjects.[29][33] 1891 marked his Constitution of the 3 May (Konstytucja 3 Maja).[29] He went on to compose another large scale work, The Oaths of Jan Kazimierz (Śluby Jana Kazimierza), but death intervened.[29] In 1892, a year before his death, he completed his Self-portrait (Autoportret).[29]

Portraits and other work

[edit]

In addition to the history paintings Matejko was a prolific portraitist.[29] His subjects included Jagiellonian University rectors Józef Szujski and Stanisław Tarnowski, and numerous portraits of family and friends, including Wife in her wedding dress ("Żona w sukni ślubnej") (1865, destroyed by his wife during a quarrel and recreated in 1879) and a self-portrait (1892).[29] Altogether Matejko authored 320 oil paintings and several thousand drawings and watercolours.[34] He also designed the monumental polychrome murals for the Brick Gothic St. Mary's Basilica, Kraków (1889–1891), which in 1978 became a UNESCO World Heritage Site alongside the Historic Centre of Kraków.[35][36]

Death

[edit]

Matejko suffered from a peptic ulcer, and died in Kraków on 1 November of internal bleeding.[31] His funeral on 5 November drew large crowds, and his death was newsworthy in at least thirty two European newspapers.[37] He was buried in Kraków's Rakowicki Cemetery.[31]

Significance, style and themes

[edit]He is counted among the most significant of Polish painters,[2][3] and considered by many as "Poland's greatest history painter"[5] or as "a cult figure for the nation at large... [already] by the time of his death.".[26] Wilhelm von Kaulbach and his "historical symbolism" style had a profound influence on Matejko. This aimed not so much at an exact representation of past events, but gave the artist freedom to interpret and opened the possibility to blend historical data within a chosen perspective. Matejko's technique in the Neoclassical genre has been praised for its "luminosity, detail and imagination".[26][38]

He succeeded in propagating Polish history, and fostering the memory of an erstwhile historic state lost to the world, while his country remained carved up between three European powers which afforded its Polish natives no prospect of political self-determination.[2] His works, disseminated through thousands of reproductions, have become standard illustrations of the many key events in Polish history.[2][3] His 1860 illustrated album, Ubiory w Polsce (Costume in Poland), is seen as a valuable historical reference.[39]

Criticism and controversy

[edit]Critics of his work have pointed to his use of traditional, outdated or bombastic painting style, discrediting him for "antiquarian realism" and "theatrical effects".[40] At exhibitions abroad, the nuanced historical context of his works was often lost on foreign audiences.[14][26] Occasionally his paintings would cause controversy. For example, Rejtan offended a number of prominent members of the Polish nobility, who saw the painting as an indictment of their entire social class.[23][26] His paintings were subject to censorship in the Russian Empire. Nazi Germany planned to destroy both The Battle of Grunwald and The Prussian Homage, which the authorities saw as an offence against the German view of history. They formed part of the very many Polish paintings and art which the Germans planned to destroy in their war on Polish culture, but the Polish resistance successfully hid both.[41]

Awards

[edit]- Chevalier de la Legion d'honneur, 1870 for his Union of Lublin 1869

- Médaille d'or at the Salon de Paris in 1867 for Rejtan

- Kunst-medaille 1873, Vienna

- Membre de l'Académie des Beaux-Arts (1873)

- Médaille d'honneur at the Exposition Universelle (1878)

- Commander's Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph[42]

- Commander's Cross of the Order of the Iron Crown

- Commander's Cross with Star of the Order of Pius IX[43]

- Gold Medal of the Munich Academy of Art

- Papal Gold Medal of Leo XIII

- Medal "Pro litteris et artibus", Vienna

- Odznaka Honorowa za Dzieła Sztuki i Umiejętności, Poland (1887)[44]

- Honorary citizenship of the cities of Kraków, Lwów, Przemyśl, Ivano-Frankivsk, Stryj and Brzezany

- Doctor honoris causa of the Jagiellonian University (1887)[45]

- Member of the Institut de France (1874), of the Berlin Academy of Arts (1874), of the Accademia Raffaello, Urbino (1878) and of the Wiener Kunstlergenossenschaft (1888).[46]

Legacy

[edit]

Matejko's aim was to focus on major themes in Polish history using historical sources to paint events in minute historical detail.[47] His earliest paintings are purely historical depictions without didactic content.[16] The later works, starting with Stańczyk (1862), are intended to inspire the viewer with a patriotic message.[16][48] Stańczyk focuses on the court jester, portrayed as a symbol of his country's conscience, sitting in a chair, against the background of a party - a lonely figure reflecting on war, ignored by the joyful crowd.[26]

His paintings are on display in numerous Polish museums, including: the National Museum in Warsaw, National Museum in Kraków, National Museum in Poznań and National Museum in Wrocław.[31] The National Museum, Kraków has a building entirely dedicated to Matejko - The Jan Matejko House (Dom Jana Matejki), occupying his former studio and family home in Floriańska Street and opened in 1898.[31][49] Another museum dedicated to Matejko, is the Jan Matejko Manor House (Dworek Jana Matejki w Krzesławicach), in the village of Krzesławice, where Matejko had bought a small estate in 1865.[24][50]

As teacher and influencer

[edit]Over 80 painters were Matejko's students, many influenced during his tenure as director of the Kraków School of Fine Arts, and are called members of the "Matejko School".[51][26][52] Some went on to become members of the brief flowering of the Young Poland (Młoda Polska) movement, which encompassed literature, music, theatre as well as visual arts and was dissipated by World War I. Matejko has been dubbed "Father of Young Poland".[53] Prominent among his students were:

- Maurycy Gottlieb[52]

- Ephraim Moses Lilien[54]

- Jacek Malczewski[52]

- Helena Matejko, Matejko's daughter

- Józef Mehoffer[52]

- Jozef Pankiewicz

- Antoni Piotrowski[52]

- Witold Pruszkowski[52]

- Jan Styka[55]

- Włodzimierz Tetmajer

- Józef Unierzyski, Matejko's son-in-law

- Leon Wyczółkowski[52]

- Stanisław Wyspiański[52]

-

Jan Kochanowski over his dead daughter's body, 1862

-

Samuel Zborowski on his way to his execution

-

Wladyslaw I Lokietek from the Gallery of Polish Monarchs

-

The Constitution of May 3. Four-Year Sejm. Educational Commission Partition. A.D. 1795 Royal Castle

-

Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God, 1873. In the background: Frombork Cathedral

-

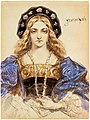

Pen and ink drawing possibly of Bona Sforza, 1861

Selected work

[edit]The following is a selected list of Matejko's works, in chronological order.

| # | Title | Year | Technique and size | Location | Illustration |

| 1. | Carowie Szujscy przed Zygmuntem III (The Shuysky Princes before King Sigismund III) | 1853 | oil on canvas 75.5 cm × 109 cm |

National Museum in Wrocław |

|

| 2. | Stańczyk | 1862 | oil on canvas 120 × 88 cm |

National Museum, Warsaw |

|

| 3. | Kazanie Skargi (Skarga's Sermon) | 1864 | oil on canvas 224 × 397 cm |

Royal Castle, Warsaw |

|

| 4. | Rejtan | 1866 | oil on canvas 282 × 487 cm |

Royal Castle, Warsaw |

|

| 5. | Alchemik Sędziwój (Alchemist Sendivogius) | 1867 | oil on canvas 73 × 130 cm |

Museum of Arts in Łódź |

|

| 6. | Unia Lubelska (Union of Lublin) | 1869 | oil on canvas 298 cm × 512 cm |

Lublin Museum |

|

| 7. | Stefan Batory pod Pskowem (Stephen Báthory at Pskov) | 1872 | oil on canvas 322 × 545 cm |

Royal Castle, Warsaw |

|

| 8. | Astronom Kopernik, czyli rozmowa z Bogiem (Astronomer Copernicus, or Conversations with God) | 1873 | oil on canvas 225 × 315 cm |

Collegium Novum |

|

| 9. | Zawieszenie dzwonu Zygmunta (The Hanging of the Sigismund bell) | 1874 | oil on wood 94 × 189 cm |

National Museum, Warsaw |

|

| 10. | Śmierć króla Przemysła II (Death of King Przemysł II) | 1875 | Modern Gallery in Zagreb |

| |

| 11. | Bitwa pod Grunwaldem (Battle of Grunwald) | 1878 | oil on canvas 426 × 987 cm |

National Museum, Warsaw |

|

| 12. | Polonia - Rok 1863 (Polonia - year 1863) | 1879 | oil on canvas 156 × 232 cm |

Czartoryski Museum, Kraków |

|

| 13. | Hołd pruski (The Prussian Homage) | 1880-82 | oil on canvas 388 × 875 cm |

National Museum, Kraków |

|

| 14. | Jan III Sobieski pod Wiedniem (John III Sobieski at Vienna) | 1883 | Vatican Museums |

| |

| 15. | Wernyhora | 1883-84 | oil on canvas 290 × 204 cm |

National Museum, Kraków |

|

| 16. | Założenie Akademii Lubrańskiego w Poznaniu (Founding of the Lubrański Academy in Poznań) | 1886 | National Museum, Poznań |

| |

| 17. | Dziewica Orleańska (Maid of Orléans) | 1886 | oil on canvas 484 x 973 cm |

National Museum, Poznań |

|

| 18. | Bitwa pod Racławicami (Battle of Racławice) | 1888 | oil on canvas 450 × 890 cm |

National Museum, Kraków |

|

| 19. | cycle Dzieje cywilizacji w Polsce (History of civilisation in Poland) | 1888-1889 | |||

| 20. | Chrzest Litwy (Baptism of Lithuania) | 1888 | oil on canvas 60 × 115.5 cm |

National Museum, Warsaw |

|

| 21. | Zaprowadzenie chrześcijaństwa (Introduction of Christianity [to Poland]) | 1889 | oil on wood 79 × 120 cm |

National Museum, Warsaw |

|

| 22. | cycle Poczet królów i książąt polskich (Fellowship of the kings and princes of Poland) | 1890-1892 | |||

| 23. | Konstytucja 3 Maja 1791 r. (Constitution of 3 May 1791) | 1891 | oil on canvas 247 cm × 446 cm |

Royal Castle, Warsaw |

|

| 24. | Carowie Szujscy przed Zygmuntem III (The Shuysky Princes before King Sigismund III) | 1892 | oil on wood 42 cm × 63 cm |

Jan Matejko House in Kraków |

|

| 25. | Self-portrait (Autoportret) | 1892 | oil on canvas 160 cm × 110 cm |

National Museum, Warsaw |

|

| 26. | Śluby Jana Kazimierza (Oath of Jan Kazimierz) | 1893 | oil on wood 315 cm × 500 cm |

National Museum, Wrocław |

|

| 27. | Wyjście żaków z Krakowa w roku 1549 (Students leaving Krakow in 1549) | 1892 | oil | National Museum in Kraków |

|

See also

[edit]- Culture of Kraków

- List of Polish painters

- Clothes in Poland (1860 illustrated album by Matejko)

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Jan Matejko: The Painter and Patriot Fostering Polish Nationalism". Info-poland.buffalo.edu. Archived from the original on 26 May 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d "History's Impact on Polish Art". Info-poland.buffalo.edu. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2011.

- ^ "Conversations with God: Jan Matejko's Copernicus, Exhibition, 21 May-22 August 2021". National Gallery London. 2021.

- ^ a b William Fiddian Reddaway (1971). The Cambridge History of Poland. CUP Archive. p. 547. GGKEY:2G7C1LPZ3RN.

- ^ Matejko Adressat des Briefes Den erlauchten Polen vom 4. Januar 1889 (in German)

- ^ Nietzsches Briefe, Ausgewählte Korrespondenz, Wahnzettel 1889

- ^ a b Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 12. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 11. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. pp. 18, 22–23. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 18. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ a b Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 25. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ Jan Matejko; Jerzy Malinowski; Krystyna Sroczyńska; Jurij Birjułow (1993). Matejko: Album (in Polish). Arkady. ISBN 9788321336527.

Matejko malował nadto dwukrotnie sceny hołdu carów Szujskich przed Zygmuntem III w 1853 i 1892 roku."

[Google Books does not display page number for this book] - ^ a b c d e Bochnak (1975), p. 185

- ^ a b Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 39. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bochnak (1975), p. 186

- ^ Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 78. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 85. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ Henryk Marek Słoczyński (2000). Matejko (in Polish). Wydawn. Dolnośląskie. p. 81. ISBN 978-83-7023-820-9.

- ^ AB (5 December 2002). "Helena z Matejków Unierzyska". Miasta.gazeta.pl. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2009.

- ^ Projekt. Prasa-Książka-Ruch. 1992. p. cxliii.

- ^ Jan Matejko (1993). Matejko: obrazy olejne : katalog. Arkady. p. 1963. ISBN 978-83-213-3652-7.

- ^ a b c d e f Bochnak (1975), p. 187

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bochnak (1975), p. 188

- ^ Stanisław Wyspiański; Maria Rydlowa (1994). Listy Stanisława Wyspiańskiego do Józefa Mehoffera, Henryka Opieńskiego i Tadeusza Stryjeńskiego (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Literackie. p. 75. ISBN 978-83-08-02562-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wanda Małaszewska. "Matejko, Jan." Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 28 May 2014, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T055919

- ^ Stowarzyszenie Historyków Sztuki (1979). Sztuka XIX wieku w Polsce (in Polish). Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe. pp. 31–32. ISBN 9788301010485.

- ^ Mieczysław Treter (1939). Matejko: osobowosc artysty, tworczosc, forma i styl (in Polish). Książnica-Atlas. p. 611.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bochnak (1975), p. 189

- ^ "The Immaculate Conception and Sobieski Rooms". vaticanstate.va. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Bochnak (1975), p. 190

- ^ Roxana Radvan; John F. Asmus; Marta Castillejo; Paraskevi Pouli; Austin Nevin (1 December 2010). Lasers in the Conservation of Artworks VIII. CRC Press. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-415-58073-1.

- ^ Barbara Ciciora-Czwórnóg (2005). Jan Matejko (in Polish). Bosz. p. 14. ISBN 978-83-89747-16-7.

- ^ Jan Matejko 1838-1893 : Gemälde, Aquarelle, Zeichnungen : Ausstellung [Jan Matejko 1838-1893: Paintings, Watercolours, Drawings: An Exhibition] (in German). 1982. Kunsthalle Nürnberg, 26.3.-25.4.1982, Herzog Anton Ulrich-Museum, Braunschweig, 16.5.-27.6.1982, Städt. Wessenberg-Gemäldegalerie, Konstanz, 11.7.-15.8.1982.

- ^ Stanisława Serafińska (1958). Jan Matejko: wspomnienia rodzinne (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Literackie. p. 575.

- ^ Griffin, Julia (2021). "Matejko, Father of 'Young Poland', a talk by Julia Griffin". National Gallery London. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Maria Szypowska (2016). Jan Matejko wszystkim znany (in Polish). Fundacja Artibus-Wurlitzer oraz Wydawn. Domu Słowa Polskiego. p. 428. ISBN 9788377858448.

- ^ Ciciora, Barbara (2006). "Jan Matejko in München" (PDF) (in German). zeitenblicke. Retrieved 5 March 2016. (PDF; 261 kB)

- ^ "WYSTAWA: Wielka rekwizytornia artysty. Stroje i kostiumy z kolekcji Jana Matejki" [EXHIBITION: Great artistic repository. Clothing and costumes in the collection of Jan Matejko.]. Muzeum Narodowe w Krakowie. 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical Dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- ^ Batorska, Danuta (1992). "The Political Censorship of Jan Matejko". Art Journal. 51 (1): 57–63. doi:10.2307/777255. JSTOR 777255.

- ^ Ciciora-Czwórnóg, Barbara. Jan Matejko. p. 56.

- ^ Krzysztofowicz-Kozakowska, Stefania.Malarstwo polskie w zbiorach za granicą. publisher, Kluszczyński. 2001, p. 12.

- ^ "Telegramy biura koresp". Czas. 190: 3. 21 August 1887.

- ^ "Doktorzy honoris causa". Jagiellonian University (in Polish).

- ^ "Kronika". Kurjer Lwowski. 335: 4. 2 December 1888.

- ^ Ian Chilvers (10 June 2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. p. 452. ISBN 978-0-19-860476-1.

- ^ Geraldine Norman (1 January 1977). Nineteenth-century Painters and Painting: A Dictionary. University of California Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-520-03328-3.

- ^ "O oddziale". Muzeum.krakow.pl. Archived from the original on 24 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Bochnak (1975), p. 191

- ^ Jarmuł, Katarzyna (2004). Nagengast, Weronika (ed.). Artyści ze Szkoły Jana Matejki (in Polish). Katowice: Muzeum Śląskie. ISBN 978-83874-5563-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h ""Artists from the School of Jan Matejko" | Event". Culture.pl. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- ^ Griffin, Julia (2021). "Matejko, Father of 'Young Poland'". National Gallery London. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Glenda Abramson (1 March 2004). Encyclopedia of Modern Jewish Culture. Routledge. p. 523. ISBN 978-1-134-42865-6.

- ^ "Considered Poland's greatest panorama painter, Jan Styka died 95 years ago today". Retrieved 29 April 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Adam Bochnak; Władysław Konopczyński (1975). "Jan Matejko". Polski Słownik Biograficzny (in Polish). Vol. XX.

- Batorska, Danuta (Spring 1992). "The Political Censorship of Jan Matejko". Art Journal. 51 (1). Uneasy Pieces: 57–63. doi:10.2307/777255. JSTOR 777255. JSTOR

External links

[edit]- Works by Jan Matejko Archived 14 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine chambroch.com

- A gallery of paintings with links to biography (289 words) and bibliographical pages (12 books).

- Matejko gallery, wawel.net

- Matejko gallery, malarze.com

- Jan Matejko, culture.pl

- "Clothing and Costumes..." From the Collection of Jan Matejko (in Polish)

- "Artists from the School of Jan Matejko"

- www.Jan-Matejko.org Archived 30 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine A website dedicated to Matejko

- 1838 births

- 1893 deaths

- 19th-century Polish male artists

- 19th-century painters of historical subjects

- 19th-century Polish painters

- People from the Free City of Kraków

- Painters from Austria-Hungary

- 19th-century war artists

- Academic art

- Artists from Kraków

- Burials at Rakowicki Cemetery

- Deaths from peritonitis

- Equine artists

- History painters

- Jagiellonian University alumni

- Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts alumni

- Academic staff of the Jan Matejko Academy of Fine Arts

- Matejko family

- Members of the Académie des beaux-arts

- Military art

- Polish Austro-Hungarians

- Polish male non-fiction writers

- Polish illustrators

- Polish male painters

- Polish people of Czech descent

- Polish Roman Catholics

- Polish war artists

- Polish portrait painters

- Recipients of the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art

- Recipients of the Legion of Honour

- Polish recipients of the Legion of Honour