Cannabis sativa

| Cannabis sativa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Female Cannabis sativa, recreational/medicinal marijuana | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Cannabaceae |

| Genus: | Cannabis |

| Species: | C. sativa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Cannabis sativa | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Cannabis |

|---|

|

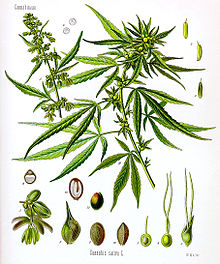

Cannabis sativa is an annual herbaceous flowering plant. The species was first classified by Carl Linnaeus in 1753.[1] The specific epithet sativa means 'cultivated'. Indigenous to Eastern Asia, the plant is now of cosmopolitan distribution due to widespread cultivation.[2] It has been cultivated throughout recorded history and used as a source of industrial fiber, seed oil, food, and medicine. It is also used as a recreational drug and for religious and spiritual purposes.

Description

[edit]

The flowers of Cannabis sativa plants are most often either male or female, but, only plants displaying female pistils can be or turn hermaphrodite. Males can never become hermaphrodites.[3] It is a short-day flowering plant, with staminate (male) plants usually taller and less robust than pistillate (female or male) plants.[4][5] The flowers of the female plant are arranged in racemes and can produce hundreds of seeds. Male plants shed their pollen and die several weeks prior to seed ripening on the female plants. Under typical conditions with a light period of 12 to 14 hours, both sexes are produced in equal numbers because of heritable X and Y chromosomes.[6] Although genetic factors dispose a plant to become male or female, environmental factors including the diurnal light cycle can alter sexual expression.[7] Naturally occurring monoecious plants, with both male and female parts, are either sterile or fertile;[clarification needed] but artificially induced "hermaphrodites" can have fully functional reproductive organs.[8] "Feminized" seed sold by many commercial seed suppliers are derived from artificially "hermaphroditic" females that lack the male gene, or by treating the plants with hormones or silver thiosulfate.

Chemical constituents

[edit]

Although the main psychoactive constituent of Cannabis is tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the plant is known to contain more than 500 compounds, among them at least 113 cannabinoids; however, most of these "minor" cannabinoids are only produced in trace amounts.[9] Besides THC, another cannabinoid produced in high concentrations by some plants is cannabidiol (CBD), which is not psychoactive but has recently been shown to block the effect of THC in the nervous system.[10] Differences in the chemical composition of Cannabis varieties may produce different effects in humans. Synthetic THC, called dronabinol, does not contain cannabidiol (CBD), cannabinol (CBN), or other cannabinoids, which is one reason why its pharmacological effects may differ significantly from those of natural Cannabis preparations.

Beside cannabinoids, the chemical constituents of Cannabis include about 120 compounds responsible for its characteristic aroma. These are mainly volatile terpenes and sesquiterpenes.

- α-Pinene[11]

- Myrcene[11]

- Linalool[11]

- Limonene[11]

- Trans-β-ocimene[11]

- α-Terpinolene[11]

- Trans-caryophyllene[11]

- α-Humulene,[11] contributes to the characteristic aroma of Cannabis sativa

- Caryophyllene,[11] with which some hashish detection dogs are trained[12]

A 1980 study identifying constituents of C. sativa[13] established 19 major chemical families (number of chemicals within group):

- Acids (18)

- Alcohols (6)

- Aldehydes (12)

- Amino Acids (18)

- Cannabinoids (55)

- Esters/Lactones (11)

- Flavanoids Glycosides (14)

- Fatty Acids (20)

- Hydrocarbons (46)

- Ketones (13)

- Nitrogenous Compounds (18)

- Non-Cannabinoid Phenols (14)

- Phytocannabinoids (111)

- Pigments (2)

- Proteins (7)

- Steroids (9)

- Sugars (32)

- Terpenes (98)

- Vitamins (1)

Cannabis also produces numerous volatile sulfur compounds that contribute to the plant's skunk-like aroma, with Prenylthiol (3-methyl-2-butene-1-thiol) identified as the primary odorant.[14] These compounds are found in much lower concentrations than the major terpenes and sesquiterpenes. However, they contribute significantly to the pungent aroma of cannabis due to their low odor thresholds as often seen with thiols or other sulfur-containing compounds.

A number of specific aromatic compounds have been implicated in variety-specific aromas.[15] These include another class of volatile sulfur compounds, referred to as tropical volatile sulfur compounds, that include 3-mercaptohexanol, 3-mercaptohexyl acetate, and 3-mercaptohexyl butyrate. These compounds possess powerful and distinctive fruity, tropical, and citrus aromas in low concentrations such as those found in certain cannabis varieties. These compounds are also important in the citrus and tropical flavors of hops, beer, wine, and tropical fruits.

In addition to volatile sulfur compounds, the heterocyclic compounds indole and skatole (3-Methyl-1H-indole) contribute to the chemical or savory aromas of certain varieties.[15] Skatole in particular was identified as a key contributor to this scent. This compound is found in mammalian feces and is used in the perfuming industry.[16] It possesses a complex aroma that is highly dependent on concentration.

Cultivation

[edit]A Cannabis plant in the vegetative growth phase of its life requires more than 16–18 hours of light per day to stay vegetative. Flowering usually occurs when darkness equals at least 12 hours per day. The flowering cycle can last anywhere between seven and fifteen weeks, depending on the strain and environmental conditions. When the production of psychoactive cannabinoids is sought, female plants are grown separately from male plants to induce parthenocarpy in the female plant's fruits (popularly called "sin semilla" which is Spanish for "without seed" ) and increase the production of cannabinoid-rich resin.[17]

In soil, the optimum pH for the plant is 6.3 to 6.8. In hydroponic growing, the nutrient solution is best at 5.2 to 5.8, making Cannabis well-suited to hydroponics because this pH range is hostile to most bacteria and fungi.[citation needed]

Tissue culture multiplication has become important in producing medically important clones,[18] while seed production remains the generally preferred means of multiplication.[19] Sativa plants have narrow leaves and grow best in warm environments. They do, however, take longer to flower than their Indica counterparts, and they grow taller than the Indica cannabis strains as well.[20]

Cultivars

[edit]Broadly, there are three main cultivar groups of cannabis that are cultivated today:

- Cultivars primarily cultivated for their fibre, characterized by long stems and little branching.[21]

- Cultivars grown for seed which can be eaten entirely raw or from which hemp oil is extracted.

- Cultivars grown for medicinal or recreational purposes, characterized by extensive branching to maximize the number of flowers.[21]

A nominal if not legal distinction is often made between industrial hemp, with concentrations of psychoactive compounds far too low to be useful for that purpose, and marijuana.

Uses

[edit]Cannabis sativa seeds are chiefly used to make hempseed oil which can be used for cooking, lamps, lacquers, or paints. They can also be used as caged-bird feed, as they provide a source of nutrients for most animals. The flowers and fruits (and to a lesser extent the leaves, stems, and seeds) contain psychoactive chemical compounds known as cannabinoids that are consumed for recreational, medicinal, and spiritual purposes. When so used, preparations of flowers and fruits (called marijuana) and leaves and preparations derived from resinous extract (e.g., hashish) are consumed by smoking, vaporising, and oral ingestion. Historically, tinctures, teas, and ointments have also been common preparations. In traditional medicine of India in particular cannabis sativa has been used as hallucinogenic, hypnotic, sedative, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory agent.[22] Terpenes have gained public awareness through the growth and education of medical and recreational cannabis. Organizations and companies operating in cannabis markets have pushed education and marketing of terpenes in their products as a way to differentiate taste and effects of cannabis.[23] The entourage effect, which describes the synergy of cannabinoids, terpenes, and other plant compounds, has also helped further awareness and demand for terpenes in cannabis products.[24]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Greg Green, The Cannabis Breeder's Bible, Green Candy Press, 2005, pp. 15-16 ISBN 9781931160278

- ^ Florian ML, Kronkright DP, Norton RE (21 March 1991). The Conservation of Artifacts Made from Plant Materials. Getty Publications. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-0-89236-160-1.

- ^ Sharma OP (2011). Plant Taxonomy (2nd ed.). Tata McGraw-Hill Education. pp. 459–. ISBN 978-1-259-08137-8.

- ^ "Cannabis sativa in Flora of North America @ efloras.org". Archived from the original on 2017-03-03. Retrieved 2017-05-21.

- ^ "The Difference Between Male and Female Cannabis Plants". United Cannabis Seeds. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Clarke R, Merlin M (1 September 2013). Cannabis: Evolution and Ethnobotany. University of California Press. pp. 16–. ISBN 978-0-520-95457-1. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ Schaffner JH (1921-01-01). "Influence of Environment on Sexual Expression in Hemp". Botanical Gazette. 71 (3): 197–219. doi:10.1086/332818. JSTOR 2469863. S2CID 85156955. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- ^ "Marijuana plant anatomy and life cycles". Leafly. Archived from the original on 2023-02-24. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ^ Aizpurua-Olaizola O, Soydaner U, Öztürk E, Schibano D, Simsir Y, Navarro P, et al. (February 2016). "Evolution of the Cannabinoid and Terpene Content during the Growth of Cannabis sativa Plants from Different Chemotypes". Journal of Natural Products. 79 (2): 324–31. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00949. hdl:1874/350973. PMID 26836472. Archived from the original on 2023-01-05. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ Russo EB (August 2011). "Taming THC: potential cannabis synergy and phytocannabinoid-terpenoid entourage effects". British Journal of Pharmacology. 163 (7): 1344–64. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01238.x. PMC 3165946. PMID 21749363.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Novak J, Zitterl-Eglseer K, Deans SG, Franz CM (2001). "Essential oils of different cultivars of Cannabis sativa L. and their antimicrobial activity". Flavour and Fragrance Journal. 16 (4): 259–262. doi:10.1002/ffj.993.

- ^ "Essential Oils". Archived from the original on 2019-12-23. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Turner, C. E.; Elsohly, M. A.; Boeren, E. G. (1980). "Constituents of Cannabis sativa L. XVII. A review of the natural constituents". Journal of Natural Products. 43 (2): 169–234. doi:10.1021/np50008a001. ISSN 0163-3864. PMID 6991645.

- ^ Oswald, Iain W. H.; Ojeda, Marcos A.; Pobanz, Ryan J.; et al. (2021-11-30). "Identification of a New Family of Prenylated Volatile Sulfur Compounds in Cannabis Revealed by Comprehensive Two-Dimensional Gas Chromatography". ACS Omega. 6 (47): 31667–31676. doi:10.1021/acsomega.1c04196. ISSN 2470-1343. PMC 8638000. PMID 34869990.

- ^ a b Oswald, Iain W. H.; Paryani, Twinkle R.; Sosa, Manuel E.; Ojeda, Marcos A.; Altenbernd, Mark R.; Grandy, Jonathan J.; Shafer, Nathan S.; Ngo, Kim; Peat, Jack R.; Melshenker, Bradley G.; Skelly, Ian; Koby, Kevin A.; Page, Michael f. Z.; Martin, Thomas J. (2023-10-12). "Minor, Nonterpenoid Volatile Compounds Drive the Aroma Differences of Exotic Cannabis". ACS Omega. 8 (42): 39203–39216. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c04496. ISSN 2470-1343. PMC 10601067. PMID 37901519.

- ^ Yokoyama, Mt; Carlson, Jr (January 1979). "Microbial metabolites of tryptophan in the intestinal tract with special reference to skatole". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 32 (1): 173–178. doi:10.1093/ajcn/32.1.173. PMID 367144.

- ^ Riboulet-Zemouli K (2020). "'Cannabis' Ontologies I: Conceptual Issues with Cannabis and Cannabinoids terminology". Drug Science, Policy and Law. 6: 1–37. doi:10.1177/2050324520945797. ISSN 2050-3245.

- ^ Arora R (2010). Medicinal Plant Biotechnology. CABI. pp. 103–. ISBN 978-1-84593-692-1. Archived from the original on 2023-04-20. Retrieved 2018-02-27.

- ^ Chandra S, Lata H, El Sohly MA (23 May 2017). Cannabis sativa L. - Botany and Biotechnology. Springer. pp. 54–. ISBN 978-3-319-54564-6.

- ^ "The Difference Between Indica and Sativa". Max's Indoor Grow Shop. 2019-12-12. Archived from the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ a b "Cannabis first domesticated 12,000 years ago: study". Phys.org. 17 July 2021. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Bonini SA, Premoli M, Tambaro S, Kumar A, Maccarinelli G, Memo M, Mastinu A (December 2018). "Cannabis sativa: A comprehensive ethnopharmacological review of a medicinal plant with a long history". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 227: 300–315. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2018.09.004. PMID 30205181. S2CID 52188193.

- ^ "Terpene Carene usage".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Goldstein Ferber, Sari (February 18, 2020). "The "Entourage Effect": Terpenes Coupled with Cannabinoids for the Treatment of Mood Disorders and Anxiety Disorders". Current Neuropharmacology. 18 (2): 87–96. doi:10.2174/1570159X17666190903103923. PMC 7324885. PMID 31481004.

External links

[edit] Data related to Cannabis sativa at Wikispecies

Data related to Cannabis sativa at Wikispecies