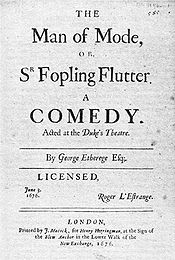

The Man of Mode

The Man of Mode, or, Sir Fopling Flutter is a Restoration comedy by George Etherege, written in 1676. The play is set in Restoration London and follows the womanizer Dorimant as he tries to win over the young heiress Harriet and to disengage himself from his affair with Mrs. Loveit. Despite the subtitle, the fop Sir Fopling is only one of several minor characters and the rake Dorimant the protagonist.

The character of Dorimant may have been based on John Wilmot, 2nd Earl of Rochester; there is no evidence of this. The part was first played by Thomas Betterton and Sir Fopling, the flamboyant fop of the hour, by William Smith. In 2007 the National Theatre produced a modern dress production of the play, directed by Nicholas Hytner and starring Tom Hardy as Dorimant. Rory Kinnear received a Laurence Olivier Award for his performance as Fopling.

Characters

[edit]- Mr. Dorimant

- Mr. Medley

- Old Bellair

- Young Bellair, in love with Emilia

- Sir Fopling Flutter

- Lady Townley, sister of Old Bellair

- Emilia

- Mrs. Loveit, in love with Dorimant

- Belinda, in love with Dorimant

- Lady Woodvill, and

- Harriet, her daughter

- Pert

- Busy

- A Shoemaker

- An Orange-Woman

- Three Slovenly Bullies

- Two Chairmen

- Mr. Smirk, a parson

- Handy, a valet de chambre

- Pages. Footmen, etc.[1]

Plot

[edit]The protagonist of The Man of Mode is Dorimant, a notorious libertine and man-about-town.

The story opens with Dorimant addressing a billet-doux to Mrs. Loveit, with whom he is having an affair, to lie about his whereabouts. An "Orange-Woman" is let in and informs him of the arrival in London of a beautiful heiress – later known to be Harriet. Dorimant's closest friend and fellow rake, Medley, arrives and offers more information on her. Dorimant expresses his wish to break off his relationship with Mrs. Loveit, being already involved with her younger friend Belinda. The two friends plot to encourage Mrs. Loveit's jealousy so that she will break off the relationship with Dorimant. Young Bellair, the handsome acquaintance of both men, enters and relates his infatuation with Emilia, a woman serving as companion to Lady Townley—his devotion is ridiculed. The three debate the fop Sir Fopling Flutter, newly come to London. Bellair learns of his father's arrival, that he lodges in the same place as his Emilia and of his desire for a different match for his son. A letter arrives from Mrs. Loveit and Dorimant departs.

Lady Townley and Emilia discuss the affairs of town, particularly Old Bellair's professing of love for Emilia and his lack of awareness about his son's affections for her; he intends instead for him to marry Harriet. Young Bellair admits to having written a letter promising his acquiescence to his father's will in due time so as to deceive him. Medley arrives and boasts to the ladies of Dorimant's womanising status.

Mrs. Loveit becomes enraged with jealousy at Dorimant's lack of attention to her, while her woman, Pert, attempts to dissuade her from such feelings. Belinda enters and informs her of a masked woman that Dorimant was seen in public with. Dorimant appears and accuses the women of spying on him and also that Mrs. Loveit has encouraged the affections of Sir Fopling; in a pretended state of jealousy, he leaves.

Harriet and Young Bellair act as if they are in love to trick the onlooking Lady Woodvill and Old Bellair. Meanwhile, Dorimant and Belinda meet at Lady Townley's and arrange an imminent meeting. Emilia then reveals her interest in Dorimant to Belinda and Lady Townley. Belinda persuades Mrs. Loveit, on Dorimant's request, to take a walk on The Mall and be 'caught' in the act of flirting with Fopling. Dorimant meets with Fopling and pretends that Mrs. Loveit has affections for him (Fopling). When Mrs. Loveit encounters Fopling she acts flirtatious, in spite of not liking him and succeeds in making Dorimant jealous. Medley suggests he attends a dance at Lady Townley's which Harriet will be, though in the disguise of "Mr Courtage", to take his mind off Mrs. Loveit. Woodvill chides Dorimant and his reputation in front of him, not seeing through his disguise. Dorimant admits to Emilia that he loves Harriet but continues to be obstinate. Fopling appears and almost uncovers Dorimant but the latter leaves to meet Belinda. She expresses her jealousy at Mrs. Loveit, imploring him to never see her again. Young Bellair discovers his father's affections for Emilia, Harriet's for Dorimant and tells Dorimant.

Belinda returns to Mrs. Loveit's in the early hours but taking the same hired chair that Mrs. Loveit had taken when she left Dorimant's, is suspected of being up to something. Dorimant arrives afterwards and confronts Mrs. Loveit; she says she is aware that he is only faking jealousy to spend time with another woman.

Lady Woodvill and Old Bellair rush their children to get married. Dorimant interrupts; his true identity is revealed when Mrs. Loveit and Belinda arrive to confront him. Mrs. Woodvill is in dismay. Young Bellair and Emilia publicly show their love for each other. Old Bellair concedes to the match and Woodvill admits that she likes Dorimant despite the gossip she has heard about him. Harriet admits she loves Dorimant, so Woodvill allows for their marriage while warning Harriet that the match will bring ruin upon her. Both young couples will marry.

Harriet advises Belinda and Mrs. Loveit to stay away from Dorimant (for their own good) and perhaps join a nunnery to preserve their goodness. Dorimant and Harriet will move back to the country to live with the Woodvills. Fopling is glad not to commit to anyone.

Genre and style

[edit]Brian Gibbons argues that the play "offers the comedy of manners in its most concentrated form".[2] John Dryden used similar themes in his 1678 work Mr. Limberham; or, the Kind Keeper, but far less successfully; the play was only performed three times and has been described as his 'most abject failure.'[3]

Notes

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Gibbons, Brian. 1984. Introduction. Five Restoration Comedies. New Mermaids Ser. London: A&C Black. ISBN 0-7136-2610-0. p.viii-xxiii.

- Lawrence, Robert G. 1994. Introduction to The Man of Mode. Restoration Plays. Everyman Ser. London: JM Dent. ISBN 0-460-87432-2. pp. 107–110.

- Scott McMillin, ed. (1997). Restoration and eighteenth-century comedy (2nd ed.). New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 0-393-96334-9.

External links

[edit]- "The Man of Mode" (PDF). (350 KB) Full text.

- John Dennis, A Defense of Sir Fopling Flutter (1722).