Immature teratoma

| Immature teratoma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Micrograph of the primitive neuroepithelium of an immature teratoma. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

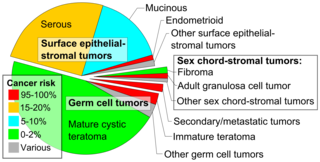

An immature teratoma is a teratoma that contains anaplastic immature elements, and is often synonymous with malignant teratoma.[1] A teratoma is a tumor of germ cell origin, containing tissues from more than one germ cell line,[2][3][4] It can be ovarian or testicular in its origin.[4] and are almost always benign.[5] An immature teratoma is thus a very rare tumor, representing 1% of all teratomas, 1% of all ovarian cancers, and 35.6% of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors.[6] It displays a specific age of incidence, occurring most frequently in the first two decades of life and almost never after menopause.[4] Unlike a mature cystic teratoma, an immature teratoma contains immature or embryonic structures. It can coexist with mature cystic teratomas and can constitute of a combination of both adult and embryonic tissue.[7][8] The most common symptoms noted are abdominal distension and masses.[9] Prognosis and treatment options vary and largely depend on grade, stage and karyotype of the tumor itself.

Diagnosis

[edit]At CT and MRI, an immature teratoma possesses characteristic appearance. It is typically large (12–25 cm) and has prominent solid components with cystic elements.[10] It is usually filled with lipid constituents and therefore demonstrates fat density at CT and MRI.[10] Ultrasound appearance of an immature teratoma is nonspecific. It is highly heterogeneous with partially solid lesions and scattered calcifications.[11][12]

Stage

[edit]Traditionally, comprehensive surgical staging is performed via exploratory laparotomy with cytologic washings, peritoneal biopsies, an omental assessment (either biopsy or rarely a full omentectomy), and both pelvic and aortic lymph node dissection. Laproscopy is often suggested as an alternative to surgically stage patients with immature teratoma.[13][14]

Ovarian cancer is staged using the FIGO staging system and uses information obtained after surgery, which can include a total abdominal hysterectomy via midline laparotomy, unilateral (or bilateral) salpingo-oophorectomy, pelvic (peritoneal) washings, assessment of retroperitoneal lymph nodes and/or appendectomy.[15][16] The AJCC staging system, identical to the FIGO staging system, describes the extent of tumor (T), the presence of absences of metastases to lymph nodes (N), the presence or absence of distant metastases (M).[17]

| Stage | Description | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Cancer is completely limited to the ovary | |||

| IA | involves one ovary, capsule intact, no tumor on ovarian surface, negative washings | |||

| IB | involves both ovaries; capsule intact; no tumor on ovarian surface; negative washings | |||

| IC | tumor involves one or both ovaries | |||

| IC1 | surgical spill | |||

| IC2 | capsule has ruptured or tumor on ovarian surface | |||

| IC3 | positive ascites or washings | |||

| II | pelvic extension of the tumor (must be confined to the pelvis) or primary peritoneal tumor, involves one or both ovaries | |||

| IIA | tumor found on uterus or fallopian tubes | |||

| IIB | tumor elsewhere in the pelvis | |||

| III | cancer found outside the pelvis or in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes, involves one or both ovaries | |||

| IIIA | metastasis in retroperitoneal lymph nodes or microscopic extrapelvic metastasis | |||

| IIIA1 | metastasis in retroperitoneal lymph nodes | |||

| IIIA1(i) | the metastasis is less than 10 mm in diameter | |||

| IIIA1(ii) | the metastasis is greater than 10 mm in diameter | |||

| IIIA2 | microscopic metastasis in the peritoneum, regardless of retroperitoneal lymph node status | |||

| IIIB | metastasis in the peritoneum less than or equal to 2 cm in diameter, regardless of retroperitoneal lymph node status; or metastasis to liver or spleen capsule | |||

| IIIC | metastasis in the peritoneum greater than 2 cm in diameter, regardless of retroperitoneal lymph node status; or metastasis to liver or spleen capsule | |||

| IV | distant metastasis (i.e. outside of the peritoneum) | |||

| IVA | pleural effusion containing cancer cells | |||

| IVB | metastasis to distant organs (including the parenchyma of the spleen or liver), or metastasis to the inguinal and extra-abdominal lymph nodes |

Pathology

[edit]

An immature teratoma contains varying compositions of adult and embryonic tissue. The most common embryonic component identified in immature teratomas is the neuroectoderm.[19] Occasionally, tumors may present neuroepithelium that resemble neuroblasts.[19] Tumors may also present embryonic components such as immature cartilage and skeletal muscle of mesodermal origin.[19] Immature teratomas composed of embryonic endodermal derivatives are rare.[19]

Often a mature cystic teratoma is misdiagnosed as its immature counterpart due to the misinterpretation of mature neural tissue as immature.[20] While mature neural cells have nuclei with uniformly dense chromatin and neither exhibit apoptotic or mitotic activity, immature neural cells have nuclei with vesicular chromatin and exhibit both apoptotic and mitotic activity.[20] A recent study has identified the use of Oct-4 as a reliable biomarker for the diagnosis of highly malignant cases of immature teratomas.[21]

Grade

[edit]Thurlbeck and Scully devised a grading system for “pure” immature teratomas on the basis of differentiation of the cellular elements of the tumor.[22] The proportion of immature tissue elements defines the grade of immaturity.[22] This was later modified by Norris et al. (1976), who added a quantitative aspect to the degree of immaturity.[23]

| Grade | Thurlbeck and Scully (1960) | Norris et al. (1976) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | All cells are well differentiated | All cells are mature; mitotic activity is rare or absent. |

| 1 | Cells are well differentiated except in rare small foci of embryonic tissue; neuroepithelium is absent or rare | Neuroepithelium absent or limited to fewer than one low-magnification field (x40) per slide |

| 2 | Moderate quantities of embryonic tissue present; cells show atypicality and mitotic activity | Neuroepithelium does not exceed more than three low-magnification fields (x40) per slide |

| 3 | Large quantities of embryonic tissue present; cells show atypicality and mitotic activity | Neuroepithelium exceeds more than three low-magnification fields (x40) per slide |

Karyotype

[edit]An ovarian immature teratoma is karyotypically normal 46,XX or near-normal. Grade 1 or 2 tumors exhibit 46,XX normal karyotype, whereas grade 3 tumors show a variety of abnormal karyotypes.[24] Though immature teratoma cells show a normal karyotype, there may still be detectable alterations in the gene level and that these aberrations may influence the stability of chromosome status.[24]

Genetics

[edit]Ovarian immature teratomas have been classified as among the least mutated of all solid cancers.[25] Immature teratomas originate from germ cells that undergo one of several meiotic failures, leading to a tumor genome with high levels of copy neutral loss of heterozygosity.[25]

Prognosis

[edit]Though several studies have shown that size and stage of the primary tumor are related to survival, the grade of the tumor is the best determinant of prognosis prior to peritoneal spread.[23][24] Once peritoneal spread has occurred, the grade of metastatic lesions or implants is the best determinant of prognosis.[23][24] Multiple sections of the primary tumor and wide sampling of the implants are necessary to properly grade the tumor. In most cases, the implants are better differentiated than the primary tumors.[8] Gliomatosis peritonei, a rare condition often associated with immature ovarian teratoma, is characterized by the presence of mature glial implants in the peritoneum.[26] Yoon et al. (2012), reported that immature ovarian teratoma patients with Gliomatosis peritonei have larger tumors, more frequent recurrence and higher CA-125 levels than immature ovarian teratoma patients without gliomatosis peritonei.[27]

A high degree of immaturity in the primary tumor, one that corresponds with a grade 3 diagnosis is a sign of poor prognosis.[23][8][28][29] Grade 3 tumors often display chromosomal abnormalities, also an indication of poor prognosis.[24] Tumor grade is the most important factor for relapse in immature teratomas.[28] Vicus et al. (2011), reported that grade 2 or 3 tumors are associated with a greater chance of relapse that can be fatal, predominantly within 2 years of diagnosis.[30] Among grade 3 patients, the stage was significantly associated with relapse.[30]

In the past, survival rates were low for high-grade immature teratomas. Norris et al. (1976), reported a survival rate of 82% for patients with grade 1 tumors, 62% for grade 2 and 30% for grade 3 tumors.[23] However, these results antedate the use of multi-agent chemotherapy.[8] With the advent of multiagent chemotherapy after surgical resection, long-term remission and increased survival rates have been achieved. Pashankar et al. (2016), reported that the estimated 5-year overall survival rate for grade 3 Stage I and II disease was 91% compared with 88% for grade 3, Stage III and IV disease.[28]

Treatment

[edit]Histologic grade and fertility desires of the patient are key considerations in determining treatment options. In adult women postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy is standard except for stage I /grade 1 disease. In pediatric patients, surgery alone is standard.[28]

Surgery

[edit]Since the occurrence of immature teratoma is very rarely bilateral, current standard of care of unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy with wide sampling of peritoneal implants.[8] Total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy are not indicated as they do not influence outcomes.[8] Fertility-sparing surgery in the form of unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the primary treatment modality in young patients.[31][32][33] Some physicians recommend ovarian cystectomy alone, rather than a unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for patients with an early stage low grade disease. Zhao et al. (2017), reported no significant differences in survival rates or post-operative fertility outcomes between the two treatment options.[34] However, others caution against such an approach.[8]

Chemotherapy

[edit]Norris et al. (1976) observed an 18% recurrence rate in grade 2 tumors and 70% recurrence in grade 3 tumors.[23] Gershenson et al. (1986), reported outcomes of 41 patients with Stage I-IV disease and observed recurrences in 94% of patients treated with surgery alone compared with 14% in patients treated with surgery and chemotherapy.[35] Studies like these resulted in the recommendation to use chemotherapy for grade 2 and 3 tumors. Currently, the use of multi agent chemotherapy for adult patients with ovarian immature teratoma is standard of care except for grade 1, stage I tumors.[28] There is considerable experience with a combination of vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide (VAC) given in an adjuvant setting; however, combinations containing cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin (BEP) are now preferred because of a lower relapse rate and shorter treatment time.[36] While a prospective comparison of VAC versus BEP has not been performed, in well-staged patients with completely resected tumors, relapse is essentially unheard of following platinum-based chemotherapy.[36] However, the disease will recur in about 25% of well-staged patients treated with 6 months of VAC.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sun H, Ding H, Wang J, Zhang E, Fang Y, Li Z, et al. (April 2019). "The differences between gonadal and extra-gonadal malignant teratomas in both genders and the effects of chemotherapy". BMC Cancer. 19 (1): 408. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-5598-0. PMC 6492338. PMID 31039746.

- ^ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- ^ Damjanov I (2009). Pathology secrets (3rd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Mosby/Elsevier. ISBN 9780323055949. OCLC 460883266.

- ^ a b c Ulbright TM (January 2004). "Gonadal teratomas: a review and speculation". Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 11 (1): 10–23. doi:10.1097/00125480-200401000-00002. PMID 14676637.

- ^ Schmidt D, Kommoss F (May 2007). "[Teratoma of the ovary. Clinical and pathological differences between mature and immature teratomas]". Der Pathologe (in German). 28 (3): 203–8. doi:10.1007/s00292-007-0909-7. PMID 17396268.

- ^ Alwazzan AB, Popowich S, Dean E, Robinson C, Lotocki R, Altman AD (November 2015). "Pure Immature Teratoma of the Ovary in Adults: Thirty-Year Experience of a Single Tertiary Care Center". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 25 (9): 1616–22. doi:10.1097/IGC.0000000000000541. PMC 4623850. PMID 26332392.

- ^ Coran AG, Adzick NS (2012). Pediatric surgery (7th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Mosby. pp. 539–548. ISBN 9780323072557. OCLC 778785699.

- ^ a b c d e f g Di Saia PJ, Creasman WT (2012). Clinical gynecologic oncology (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 329–356. ISBN 9780323074193. OCLC 785577276.

- ^ Ki EY, Byun SW, Choi YJ, Lee KH, Park JS, Lee SJ, Hur SY (2013-06-21). "Clinicopathologic review of ovarian masses in Korean premenarchal girls". International Journal of Medical Sciences. 10 (8): 1061–7. doi:10.7150/ijms.6216. PMC 3691806. PMID 23801894.

- ^ a b Malkasian GD, Symmonds RE, Dockerty MB (June 1965). "Malignant Ovarina Teratomas. Report of 31 Cases". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 25: 810–4. PMID 14287472.

- ^ Brammer HM, Buck JL, Hayes WS, Sheth S, Tavassoli FA (July 1990). "From the archives of the AFIP. Malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary: radiologic-pathologic correlation". Radiographics. 10 (4): 715–24. doi:10.1148/radiographics.10.4.2165627. PMID 2165627.

- ^ Moş C (2009). "Ovarian dermoid cysts: ultrasonographic findings" (PDF). Pictorial Essay Medical Ultrasonography. 11: 61–66. S2CID 5944732. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-04-20.

- ^ Nishida M, Kawano Y, Yuge A, Nasu K, Matsumoto H, Narahara H (2014-09-03). "Three cases of immature teratoma diagnosed after laparoscopic operation". Clinical Medicine Insights: Case Reports. 7: 91–4. doi:10.4137/CCRep.S17455. PMC 4159361. PMID 25232281.

- ^ Brown KL, Barnett JC, Leath CA (March 2015). "Laparoscopic staging of ovarian immature teratomas: a report on three cases". Military Medicine. 180 (3): e365-8. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-14-00288. PMID 25735031.

- ^ Longo DL (2012). Harrison's principles of internal medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071748896. OCLC 288932926.

- ^ a b Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC, Ledermann JA (October 2014). "Ovarian cancer". Lancet. 384 (9951): 1376–88. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62146-7. PMID 24767708.

- ^ "How is Ovarian Cancer Staged?". American Cancer Society.

- ^ - Vaidya S, Sharma P, KC S, Vaidya SA (2014). "Spectrum of ovarian tumors in a referral hospital in Nepal". Journal of Pathology of Nepal. 4 (7): 539–543. doi:10.3126/jpn.v4i7.10295. ISSN 2091-0908.

- Minor adjustment for mature cystic teratomas (0.17 to 2% risk of ovarian cancer): Mandal S, Badhe BA (2012). "Malignant transformation in a mature teratoma with metastatic deposits in the omentum: a case report". Case Reports in Pathology. 2012: 568062. doi:10.1155/2012/568062. PMC 3469088. PMID 23082264. - ^ a b c d Weidner N (2009). Modern surgical pathology (2nd ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 9781416039662. OCLC 460883320.

- ^ a b Nucci MR, Oliva E (2009). Gynecologic pathology : a volume in the series foundations in diagnostic pathology. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elservier. pp. 501–538. ISBN 9780443069208. OCLC 460883296.

- ^ Abiko K, Mandai M, Hamanishi J, Matsumura N, Baba T, Horiuchi A, et al. (December 2010). "Oct4 expression in immature teratoma of the ovary: relevance to histologic grade and degree of differentiation". The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. 34 (12): 1842–8. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181fcd707. PMID 21107090.

- ^ a b c Thurlbeck WM, Scully RE (July 1960). "Solid teratoma of the ovary. A clinicopathological analysis of 9 cases". Cancer. 13 (4): 804–11. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(196007/08)13:4<804::AID-CNCR2820130423>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 13838271.

- ^ a b c d e f g Norris HJ, Zirkin HJ, Benson WL (May 1976). "Immature (malignant) teratoma of the ovary: a clinical and pathologic study of 58 cases". Cancer. 37 (5): 2359–72. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5<2359::AID-CNCR2820370528>3.0.CO;2-Q. PMID 1260722.

- ^ a b c d e Ihara T, Ohama K, Satoh H, Fujii T, Nomura K, Fujiwara A (December 1984). "Histologic grade and karyotype of immature teratoma of the ovary". Cancer. 54 (12): 2988–94. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19841215)54:12<2988::AID-CNCR2820541229>3.0.CO;2-U. PMID 6498772.

- ^ a b Heskett MB, Sanborn JZ, Boniface C, Goode B, Chapman J, Garg K, et al. (June 2020). "Multiregion exome sequencing of ovarian immature teratomas reveals 2N near-diploid genomes, paucity of somatic mutations, and extensive allelic imbalances shared across mature, immature, and disseminated components". Modern Pathology. 33 (6): 1193–1206. doi:10.1038/s41379-019-0446-y. PMC 7286805. PMID 31911616.

- ^ Liang L, Zhang Y, Malpica A, Ramalingam P, Euscher ED, Fuller GN, Liu J (December 2015). "Gliomatosis peritonei: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 21 cases". Modern Pathology. 28 (12): 1613–20. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2015.116. PMC 4682736. PMID 26564007.

- ^ Yoon NR, Lee JW, Kim BG, Bae DS, Sohn I, Sung CO, Song SY (September 2012). "Gliomatosis peritonei is associated with frequent recurrence, but does not affect overall survival in patients with ovarian immature teratoma". Virchows Archiv. 461 (3): 299–304. doi:10.1007/s00428-012-1285-0. PMID 22820986.

- ^ a b c d e Pashankar F, Hale JP, Dang H, Krailo M, Brady WE, Rodriguez-Galindo C, et al. (January 2016). "Is adjuvant chemotherapy indicated in ovarian immature teratomas? A combined data analysis from the Malignant Germ Cell Tumor International Collaborative". Cancer. 122 (2): 230–7. doi:10.1002/cncr.29732. PMC 5134834. PMID 26485622.

- ^ Nogales FF, Favara BE, Major FJ, Silverberg SG (November 1976). "Immature teratoma of the ovary with a neural component ("solid" teratoma). A clinicopathologic study of 20 cases". Human Pathology. 7 (6): 625–42. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(76)80076-7. PMID 992645.

- ^ a b Vicus D, Beiner ME, Clarke B, Klachook S, Le LW, Laframboise S, Mackay H (October 2011). "Ovarian immature teratoma: treatment and outcome in a single institutional cohort". Gynecologic Oncology. 123 (1): 50–3. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.037. PMID 21764111.

- ^ Tay SK, Tan LK (January 2000). "Experience of a 2-day BEP regimen in postsurgical adjuvant chemotherapy of ovarian germ cell tumors". International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 10 (1): 13–18. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1438.2000.00010.x. PMID 11240646.

- ^ Kanazawa K, Suzuki T, Sakumoto K (June 2000). "Treatment of malignant ovarian germ cell tumors with preservation of fertility: reproductive performance after persistent remission". American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 23 (3): 244–8. doi:10.1097/00000421-200006000-00007. PMID 10857886.

- ^ Low JJ, Perrin LC, Crandon AJ, Hacker NF (July 2000). "Conservative surgery to preserve ovarian function in patients with malignant ovarian germ cell tumors. A review of 74 cases". Cancer. 89 (2): 391–8. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20000715)89:2<391::AID-CNCR26>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 10918171.

- ^ Zhao T, Liu Y, Wang X, Zhang H, Lu Y (April 2017). "Ovarian cystectomy in the treatment of apparent early-stage immature teratoma". The Journal of International Medical Research. 45 (2): 771–780. doi:10.1177/0300060517692149. PMC 5536676. PMID 28415950.

- ^ Gershenson DM, del Junco G, Silva EG, Copeland LJ, Wharton JT, Rutledge FN (November 1986). "Immature teratoma of the ovary". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 68 (5): 624–9. PMID 3763073.

- ^ a b Williams S, Blessing JA, Liao SY, Ball H, Hanjani P (April 1994). "Adjuvant therapy of ovarian germ cell tumors with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 12 (4): 701–6. doi:10.1200/JCO.1994.12.4.701. PMID 7512129.

- ^ Slayton RE, Park RC, Silverberg SG, Shingleton H, Creasman WT, Blessing JA (July 1985). "Vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide in the treatment of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study (a final report)". Cancer. 56 (2): 243–8. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19850715)56:2<243::AID-CNCR2820560206>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 2988740.

External links

[edit]- Immature teratoma entry in the public domain NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Dictionary of Cancer Terms. U.S. National Cancer Institute.

This article incorporates public domain material from Dictionary of Cancer Terms. U.S. National Cancer Institute.