Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (March 2018) |

| Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Malignant schwannoma,[1] Neurofibrosarcoma,[1] and Neurosarcoma[1] |

| |

| Micrograph of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour with the typical herringbone pattern. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Neuro-oncology |

A malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) is a form of cancer of the connective tissue surrounding peripheral nerves. Given its origin and behavior it is classified as a sarcoma. About half the cases are diagnosed in people with neurofibromatosis; the lifetime risk for an MPNST in patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 is 8–13%.[2] MPNST with rhabdomyoblastomatous component are called malignant triton tumors.

The first-line treatment is surgical resection with wide margins. Chemotherapy and often radiotherapy are done as adjuvant and/or neoadjuvant treatment depending upon various risk factors.

Signs and symptoms

[edit]

Symptoms may include:

- Swelling in the extremities (arms or legs), also called peripheral edema; the swelling often is painless.

- Difficulty in moving the extremity that has the tumor, including a limp.

- Soreness localized to the area of the tumor or in the extremity.

- Neurological symptoms.[3]

- Pain or discomfort: numbness, burning, or "pins and needles".[3]

- Dizziness and/or loss of balance.[3]

Causes

[edit]Soft tissue sarcomas have been linked within families, so it is hypothesized that neurofibrosarcoma may be genetic, although researchers still do not know the exact cause of the disease. Evidence supporting this hypothesis includes loss of heterozygosity on the 17p chromosome. The p53 (a tumor suppressor gene in the normal population) genome on 17p in neurofibrosarcoma patients is mutated, increasing the probability of cancer. The normal p53 gene will regulate cell growth and inhibit any uncontrollable cell growth in the healthy population; since p53 is inactivated in neurofibrosarcoma patients, they are much more susceptible to developing tumors.

Genetics

[edit]

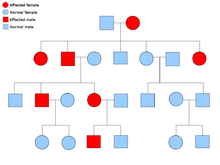

A malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor is rare, but is one of the most common frequent soft tissue sarcoma in the pediatrics population. About half of these cases also happen to occur along with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1), which is a genetic mutation on the 17th chromosome which causes tumors along the nervous system. The lifetime risk of patients with NF-1 developing MPNST has been estimated at 8–13%, while those with only MPNST have a 0.001% in the general population.[4] NF-1 and MPNST are categorized as autosomal dominant disorders. This means when one receives an abnormal gene from one of their parents, they will ultimately have that disorder. That person has a 50/50 chance of passing on that gene to their offspring. The pedigree to the right describes this genetic pattern.

Diagnosis

[edit]The most conclusive test for a patient with a potential neurofibrosarcoma is a tumor biopsy (taking a sample of cells directly from the tumor itself). MRIs, X-rays, CT scans, and bone scans can aid in locating a tumor and/or possible metastasis.

Classification

[edit]Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors are a rare type of cancer that arise from the soft tissue that surrounds nerves. They are a type of sarcoma. Most malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors arise from the nerve plexuses that distribute nerves into the limbs—the brachial and lumbar plexuses—or from nerves as they arise from the trunk.[5]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment for neurofibrosarcoma is similar to that of other cancers. Surgery is an option; the removal of the tumor along with surrounding tissue may be vital for the patient's survival. For discrete, localized tumors, surgery is often followed by radiation therapy of the excised area to reduce the chance of recurrence. For patients who have neurofibrosarcomas in an extremity, if the tumor is vascularized (has its own blood supply) and has many nerves going through it and/or around it, amputation of the extremity may be necessary. Some surgeons argue that amputation should be the procedure of choice when possible, due to the increased chance of a better quality of life. Otherwise, surgeons may opt for a limb-saving treatment, by removing less of the surrounding tissue or part of the bone, which is replaced by a metal rod or grafts. Radiation will also be used in conjunction with surgery, especially if the limb was not amputated. Radiation is rarely used as a sole treatment. In some instances, the oncologist may choose chemotherapy drugs when treating a patient with neurofibrosarcoma, usually in conjunction with surgery. Patients taking chemotherapy must be prepared for the side effects that come with any other chemotherapy treatment, such as; hair loss, lethargy, weakness, etc.

Prognosis

[edit]Patient response to treatment will vary based on age, health, and the tolerance to medications and therapies.

Metastasis occurs in about 39% of patients, most commonly to the lung. Features associated with poor prognosis include a large primary tumor (over 5 cm across), high grade disease, co-existent neurofibromatosis, and the presence of metastases.[5]

It is a rare tumor type, with a relatively poor prognosis in children.[6]

In addition, MPNSTs are extremely threatening in NF1. In a 10-year institutional review for the treatment of chemotherapy for MPNST in NF1, which followed the cases of 1 per 2,500 in 3,300 live births, chemotherapy did not seem to reduce mortality, and its effectiveness should be questioned. Although with recent approaches with the molecular biology of MPNSTs, new therapies and prognostic factors are being examined.[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ^ Evans DG, Baser ME, McGaughran J, Sharif S, Howard E, Moran A (May 2002). "Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours in neurofibromatosis 1". Journal of Medical Genetics. 39 (5): 311–314. doi:10.1136/jmg.39.5.311. PMC 1735122. PMID 12011145.

- ^ a b c Valeyrie-Allanore L, Ismaïli N, Bastuji-Garin S, Zeller J, Wechsler J, Revuz J, Wolkenstein P (July 2005). "Symptoms associated with malignancy of peripheral nerve sheath tumours: a retrospective study of 69 patients with neurofibromatosis 1". The British Journal of Dermatology. 153 (1): 79–82. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06558.x. PMID 16029330. S2CID 41984803.

- ^ Ferrari A, Bisogno G, Carli M (2007). "Management of childhood malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor". Paediatric Drugs. 9 (4): 239–248. doi:10.2165/00148581-200709040-00005. PMID 17705563. S2CID 11894017.

- ^ a b Panigrahi S, Mishra SS, Das S, Dhir MK (August 2013). "Primary malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor at unusual location". Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 4 (Suppl 1): S83 – S86. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.116480. PMC 3808069. PMID 24174807.

- ^ Neville H, Corpron C, Blakely ML, Andrassy R (March 2003). "Pediatric neurofibrosarcoma". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 38 (3): 343–6, discussion 343–6. doi:10.1053/jpsu.2003.50105. PMID 12632346.

- ^ Zehou O, Fabre E, Zelek L, Sbidian E, Ortonne N, Banu E, et al. (August 2013). "Chemotherapy for the treatment of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors in neurofibromatosis 1: a 10-year institutional review". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 8 (1): 127. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-8-127. PMC 3766199. PMID 23972085.