Makin (atoll)

| |

| |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

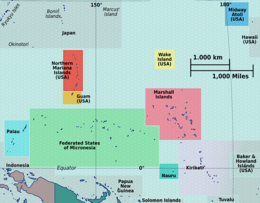

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 3°23′N 173°00′E / 3.383°N 173.000°E |

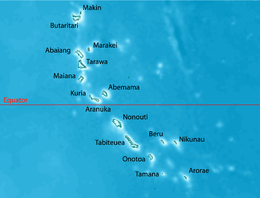

| Archipelago | Gilbert Islands |

| Area | 7.89 km2 (3.05 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3 m (10 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 1,990 (2015 Census) |

| Pop. density | 228/km2 (591/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | I-Kiribati 98.5% |

Makin is an atoll, chain of islands, located in the Pacific Ocean island nation of Kiribati. Makin is the northernmost of the Gilbert Islands, with a population (in 2015) of 1,990.[1]

Geography

[edit]

Makin is located six km northeast of the northeastern corner of Butaritari atoll reef and 6.9 km from the Butaritari islet of Namoka. It is a linear reef feature, 12.3 km long north-south, with five islets, the two larger ones being inhabited (Makin and Kiebu). The third largest, and southernmost islet, Onne, is also inhabitable. This string of islands is the northernmost feature of the Gilbert Islands, and the third most northerly in the island nation of Kiribati (only Teraina and Tabuaeran of the Line Islands are more northerly). Makin is not a true atoll, but since the largest and northernmost of the islets, also called Makin, has a nearly landlocked lagoon, 0.3 km2 in size and connected to the open sea in the east only through a 15 metre wide channel (with a road bridge over it), it might be considered a degenerate atoll. Kiebu, the second largest islet, has an even smaller, completely landlocked lagoon on its eastern side, with about 80 m in diameter (making an area of about 0.005 km2 or 0.5 hectares) and at distance of 60 m to the open sea.[2]

Since neighboring Butaritari was called Makin Atoll by the U.S. military, the feature used to be called Makin Meang (Northern Makin) or Little Makin to distinguish it from the larger atoll. Now that Butaritari has become the preferred name for that larger atoll, speakers tend to drop the qualifier for Makin.

The Gilbert islands are sometimes regarded as the southern continuation of the Ratak Chain of the Marshall Islands, which are NNW of it. The closest island of the Marshall Islands, Nadikdik Atoll, is 290 km NNW of Makin.

Makin has a land area of 6.7 km2 and a population of 1,798 (census of 2010[1]).

Islets and Villages

[edit]Makin island consists of five small islets. Of these, only Makin and Kiebu islands are permanently inhabited. The total population of Makin is 1,798 (2010 Census).

| Makin: Population and Land Area | ||||

| Islet/Village | Population 2010[1] | Land area (usable)[1] | Density | Area not available for use[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Little Makin | 1,364 | 1,541.5 acres (624 ha) | 0.9 people per acre | Enclosed lagoon 84.7 acres |

| Bikin Eitei | 8 acres (3 ha) | |||

| Aonibike | 30.9 acres (13 ha) | |||

| Tebua Tarawa | 5 acres (2 ha) | |||

| Kiebu | 434 | 242.2 acres (98 ha) | 1.8 people per acre | |

| Onne | 122.6 acres (50 ha) | |||

| Makin Total | 1,798 | 1,950.2 acres (789 ha) | 0.9 people per acre | Enclosed lagoon 84.7 acres |

Climate

[edit]The climate is very similar to neighboring Butaritari atoll, with lush vegetation and high rainfall. Typical annual rainfall is about 4 m, compared with about 2 m on Tarawa Atoll and 1 m in the far south of Kiribati. Rainfall on Makin is enhanced during an El Niño.[2]

Environmental issues

[edit]Higher sea levels are resulting in saltwater intrusion to bwabwai or babai (Cyrtosperma merkusii or giant swamp taro) pits and coastal erosion.[3] At Kiebu islet, one communal bwabwai pit is located very close to a saltwater pond. When it rains the pond overflows causing damage to the bwabwai plants. More recently, the increasing incidence of unusually high tides has caused the intrusion of saltwater into the communal pit, resulting in salt contamination and damage of food crops.[2] The construction of causeways have also resulted to reduced flushing of the lagoon that has resulted in low levels of oxygen in the lagoon, which has caused damage to fish stocks in the lagoon and causes other biological problems.[3] The erosion and accretion that are occurring along the shoreline is identified as being linked to aggregate mining, land reclamation and the construction of causeways that has been thought to change the currents along the shoreline.[3]

Economy

[edit]Makin, like other Kiribati islands, has a mainly subsistence economy. Most houses are made from local materials, and most households rely on fish, coconut and fruit (particularly banana and papaya) as the mainstay of their diet, though imported rice, sugar and tobacco are also seen as necessities. Makin is a high producer of copra, but has few other economic activities apart from a limited number of Government and Island Council jobs. Many families receive remittances from relatives working on South Tarawa or overseas.[4]

Myths and legends

[edit]There are different stories told as to the creation of Makin and the other islands in the Gilberts. An important legend in the culture of Makin is that spirits who lived in a tree in Samoa migrated northward carrying branches from the tree, Te Kaintikuaba, which translates as the tree of life.[3] It was these spirits, together with Nareau the Wise who created the islands of Tungaru (the Gilbert Islands).[Note 1]

Nakaa Beach is located at the northern tip of Makin Atoll is an important site in the traditional mythology of the island group, being the departing point for the spirits of the dead heading to the underworld. Nakaa is the legendary guardian of the gateway to the place of the dead.[2]

History

[edit]In 1606 Pedro Fernandes de Queirós sighted Butaritari and Makin, which he named the Buen Viaje (‘good trip’ in Spanish) Islands.[7][8]

Traditionally, Butaritari and Makin were ruled by a chief or Uea who lived on Butaritari Island.[9] This chief had all the powers and authority to make and impose decision for Butaritari and Makin, a system very different from the southern Gilbert Islands where power was wielded collectively by the unimwane or old men. The last Uea was Nauraura Nakoriri who was in power both before and after the Gilberts became a British Protectorate in 1892.[9]

The island was surveyed in 1841 by the US Exploring Expedition.[10]

Little Makin Post Office opened around 1925.[11]

World War II

[edit]Japanese forces occupied the island in December 1941, days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, in order to protect their south-eastern flank from allied counterattacks, and isolate Australia, under the codename Operation FS. On 17–18 August 1942, in order to divert Japanese attention from the Solomon Islands and New Guinea areas, the United States launched a raid on the nearby island of Butaritari, known as the raid on Makin. The United States invaded and captured the island after the Battle of Makin, which lasted from November 20, 1943, to November 24, 1943, as well as neighbouring Tarawa island, during the Gilbert Islands campaign.

Tourism

[edit]Makin Airport, located immediately northeast of Makin Village, between the lagoon and the sea, has ICAO code NGMN and IATA code MTK. It is served by two weekly Air Kiribati flights to Butaritari and to Bonriki International Airport in Tarawa.

There are no tourist facilities on Makin, but both the Kiribati Protestant Church and the Island Council maintain guest houses.[12]

References in popular culture

[edit]Makin is featured in Call of Duty: World at War, in the first single player level ‘Semper Fi’, and two multi-player maps, 'Makin' and 'Makin Day'. It also features as a campaign location in the game Medal of Honor: Pacific Assault as 'Makin Atoll'

W.E.B. Griffin's novel Call To Arms, Book Two of The Corps series, focuses on the forming of the Marine Raiders and the raid on Makin Island, as told through the novel's protagonist, Lt. Kenneth 'Killer' McCoy.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Sir Arthur Grimble, cadet administrative officer in the Gilberts from 1914 and resident commissioner of the Gilbert and Ellice Islands colony from 1926, recorded the myths and oral traditions of the Kiribati people. He wrote the best-sellers A Pattern of Islands (London, John Murray 1952,[5] and Return to the Islands (1957), which was republished by Eland, London in 2011, ISBN 978-1-906011-45-1. He also wrote Tungaru Traditions: writings on the atoll culture of the Gilbert Islands, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1989, ISBN 0-8248-1217-4.[6]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Kiribati Census Report 2010 Volume 1" (PDF). National Statistics Office, Ministry of Finance and Economic Development, Government of Kiribati. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ a b c d "1. Makin" (PDF). Office of Te Beretitent - Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ a b c d Dr Temakei Tebano & others (August 2008). "Island/atoll climate change profiles - Makin Atoll". Office of Te Beretitent - Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series (for KAP II (Phase 2). Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ "Makin Island Report". Government of Kiribati.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Grimble, Arthur (1981). A Pattern of Islands. Penguin Travel Library. Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-009517-9.

- ^ Grimble, Arthur (1989). Tungaru traditions: writings on the atoll culture of the Gilbert Islands. Penguin Travel Library. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1217-1.

- ^ Maude, H.E. (1959). "Spanish Discoveries in the Central Pacific: A Study in Identification". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 68 (4): 284–326.

- ^ Kelly, Celsus, O.F.M. La Australia del Espiritu Santo. The Journal of Fray Martín de Munilla O.F.M. and other documents relating to the Voyage of Pedro Fernández de Quirós to the South Sea (1605–1606) and the Franciscan Missionary Plan (1617–1627) Cambridge, 1966, p.39, 62.

- ^ a b Dr Temakei Tebano & others (September 2008). "Island/atoll climate change profiles - Butaritari Atoll". Office of Te Beretitent - Republic of Kiribati Island Report Series (for KAP II (Phase 2). Archived from the original on November 6, 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ Stanton, William (1975). The Great United States Exploring Expedition. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 245. ISBN 0520025571.

- ^ Premier Postal History. "Post Office List". Premier Postal Auctions. Retrieved 5 July 2013.

- ^ "Kiribati Tourism - Outer Islands Accommodation Guide". Government of Kiribati. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2013.