Macrauchenia

| Macrauchenia Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of M. patachonica (larger) and Phenacodus primaevus (smaller) at American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | †Litopterna |

| Family: | †Macraucheniidae |

| Subfamily: | †Macraucheniinae |

| Genus: | †Macrauchenia Owen, 1838 |

| Type species | |

| †Macrauchenia patachonica Owen, 1838

| |

| |

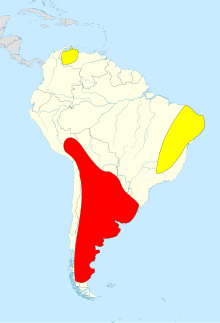

| Map showing the distribution of Macrauchenia in red, and Xenorhinotherium in yellow, inferred from fossil finds | |

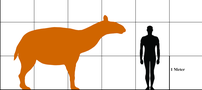

Macrauchenia ("long llama", based on the now-invalid llama genus, Auchenia, from Greek "big neck") is an extinct genus of large ungulate native to South America from the Pliocene[1] or Middle Pleistocene to the end of the Late Pleistocene.[2] It is a member of the extinct order Litopterna, a group of South American native ungulates distinct from the two orders which contain all living ungulates which had been present in South America since the early Cenozoic, over 60 million years ago, prior to the arrival of living ungulates in South America around 2.5 million years ago as part of the Great American Interchange.[3] The bodyform of Macrauchenia has been described as similar to a camel,[4] being one of the largest-known litopterns, with an estimated body mass of around 1 tonne.[3] The genus gives its name to its family, Macraucheniidae, which like Macrauchenia typically had long necks and three-toed feet, as well as a retracted nasal region,[5] which in Macrauchenia manifests as the nasal opening being on the top of the skull between the eye sockets.[6] This has historically been argued to correspond to the presence of a tapir-like proboscis, though recent authors suggest a moose-like prehensile lip[7] or a saiga antelope-like nose to filter dust are more likely.

Only one species is generally considered valid,[8] M. patachonica, which was described by Richard Owen based on remains discovered by Charles Darwin during the voyage of the Beagle.[9] M. patachonica is primarily known from localities in the Pampas, but is known from remains found across the Southern Cone extending as far south as southernmost Patagonia, and as far north as Southern Peru. Another genus of macraucheniid Xenorhinotherium was present in northeast Brazil and Venezuela during the Late Pleistocene.[6]

Macrauchenia is thought to have been a mixed feeder that both consumed woody vegetation and grass that lived in herds and probably engaged in seasonal migrations. Macrauchenia is suggested to have been a swift runner that was capable of moving at considerable speed.

Macrauchenia became extinct as part of the end-Pleistocene extinction event around 12,000 years ago, along with the vast majority of other large mammals native to the Americas.[3] This followed the arrival of humans to the Americas, and possible evidence of human interactions with Macrauchenia has been found at a number of sites with some authors suggesting human hunting may have played a role in its extinction.

Taxonomy

[edit]

Macrauchenia fossils were first collected on 9 February 1834 at Port St Julian in southern Patagonia in what is now Argentina by Charles Darwin, when HMS Beagle was surveying the port (the Argentine Confederation claimed the region but did not effectively control it at the time).[10] As a non-expert he tentatively identified the leg bones and fragments of spine he found as "some large animal, I fancy a Mastodon". In 1837, soon after the Beagle's return, the anatomist Richard Owen identified the bones, including vertebrae from the back and neck, as from a gigantic creature resembling a llama or camel, which Owen named Macrauchenia patachonica.[11] In naming it, Owen noted the original Greek terms µακρος (makros, large or long) and αυχην (auchèn, neck), as used by Illiger as the basis of Auchenia as a generic name for the llama, Vicugna and so on.[12]

Macrauchenia patachonica is currently considered to be the only valid species of Macrauchenia.[8] Macrauchenia boliviensis from the probably early Miocene aged Kollukollu Formation of Bolivia described by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1860 is now considered to be an indeterminate member of Macraucheniidae.[13] The species Macrauchenia ensenadensis described by Florentino Ameghino in 1888 from the Early Pleistocene has been transferred to the closely related genus Macraucheniopsis.[14]

Evolution

[edit]Macrauchenia is part of the extinct ungulate order Litopterna, which is grouped with several other orders as part of the South American native ungulates (SANUs), which formed a conspicuous element of South America's Cenozoic mammal fauna beginning during the Paleocene, over 60 million years ago.[15] Litopterns generally have body forms similar to those of living ungulates.[15]

The relationships of litopterns (as well as other SANUs) to living mammals was historically uncertain. Sequences of mitochondrial DNA extracted from remains of M. patachonica found in a cave in southern Chile published in 2017 indicates that the closest living relatives of Macrauchenia (and by inference, Litopterna) are members of the extant ungulate order Perissodactyla (which includes the equids, rhinoceroses, and tapirs), with litopterns estimated to have genetically diverged from perissodactyls around 66 million years ago.[16][17] Analysis of collagen sequences obtained from Macrauchenia and the contemporaneous large rhinoceros-like South American ungulate Toxodon, which belongs to another SANU order, Notoungulata, in 2015 reached a similar conclusion and suggests that litopterns are more closely related to notoungulates than to perissodactyls.[18][19]

The earliest known fossils of litopterns are from the early Paleocene, around 62.5 million years ago.[1] The family to which Macrauchenia belongs, Macraucheniidae, first appeared during the Late Eocene or Oligocene, around 39-30 million years ago, depending on what species are included.[1][20] Members of the family are typically characterised by having three-toed feet and long necks.[20] The family reached its apex of diversity in the Late Miocene, around 10-6 million years ago, before declining to low diversity during the Pliocene and Pleistocene,[20] as part of a broader decline of SANU diversity during this period.[15] The cause of this diversity decline is uncertain, though it has been suggested to be due to climatic changes,[21] as well as possibly competition/predation from immigrants from North America, who arrived following the formation of the Isthmus of Panama during the Pliocene as part of an event called the Great American Interchange.[15][22] The earliest fossils attributed to Macrauchenia date to the late Pliocene,[5] though remains of Macrauchenia patachonica are primarily known from the Late Pleistocene.[14]

Cladogram of Macraucheniidae after Lobo, Gelfo & Azevedo (2024):[20]

| Macraucheniidae |

| ||||||

Description

[edit]

Macrauchenia had a bodyform superficially like a camel,[23] with a long neck composed of camel or giraffe-like elongated cervical vertebrae. In most of the cervical vertebrae, the canal for the artery passes through the neural arch.[24] Macrauchenia was one of the largest macraucheniids and South American native ungulates, with an estimated body mass of around 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb),[24] considerably larger than earlier macraucheniids, which generally only weighed around 80–120 kilograms (180–260 lb).[3]

Skull

[edit]

The skull of Macrauchenia is relatively elongate and has an eye socket (orbit) entirely enclosed by bone, which is situated behind the teeth.[24] Like other macraucheniids, there are a total of 44 teeth in the upper and lower jaws (the primitive number in placental mammals).[20] The teeth form a continuous row on both jaws without any diastema (gaps) and they are all brachydont (low crowned).[24] The most unusual feature of Macrauchenia's skull is its retracted nasal region, shared with other derived macraucheniines, which have the opening on the top of the skull roof between the eyesockets.[24][25] Behind the nasal opening there is a substantially depressed region with numerous pits and ridges, which served as attachments for the nasal muscles. While historically this unusual nasal structure was taken as evidence for a tapir-like probiscis/trunk, recent authors have expressed doubts about this, alternatively suggesting that it may have instead formed a moose-like prehensile lip, or a saiga antelope-like nasal structure which served to filter dust (which was likely prevalent in the environment where Macrauchenia lived),[24] perhaps combining the function of dust filtering organ and a prehensile lip.[26] Behind the nasal opening, the top of the skull shows the development of extensive sinuses.[27]

Limbs

[edit]

The humerus bone is very short and robust. The radius and ulna in the forelimbs and the tibia and fibula in the hindlimbs are fused to each other, with the combined radius-ulna bone being broad in front view, and the fibula is much more slender than the tibia. The femur has a well developed third trochanter, and is long relative to the length of the tibia. The forefeet and hindfeet each had three functional digits.[24] The development of a suprapatellar fossa (an indentation) on the knee joint has led to suggestions that this functioned analogously to the stay apparatus found in living horses, allowing the knees to be passively locked while standing.[28]

Distribution

[edit]Fossils of Macrauchenia are known from across the Southern Cone, ranging from northern Chile, southern Peru, southern Bolivia, and the Pampas in Uruguay, northern Argentina and southern Brazil, southwards to extreme southernmost part of Patagonia in southern Chile and Argentina. Macrauchenia is thought to have primarily inhabited arid, open environments with only scattered woody vegetation. A closely related genus, Xenorhinotherium, inhabited more tropical environments in eastern Brazil and Venezuela.[6]

Paleobiology

[edit]

Analysis of dental calculus extracted from the teeth of an individual of Macrauchenia suggests that it was a mixed feeder (engaging in both browsing and grazing), with this individual having a diet predominantly consisting of C3 grasses.[29] Dental microwear analysis of another individual also supports grazing being an important part of the diet for Macrauchenia.[6] Like living perissodactyls, litopterns including Macrauchenia were probably hindgut fermenters.[30] A 2022 study suggested that based on the anatomy of the cervical vertebrae Macrauchenia likely held its neck in an erect posture when at rest and browsing, similar to that of a llama, though the neck was highly flexible and able to adopt many postures including being lowered to the ground for feeding, as well as being able to flex side to side.[26] Its elongated neck likely allowed it to efficiently browse vegetation without wasting energy.[24] It has been speculated that Macrauchenia may have sometimes reared up onto its hind legs like a gerenuk when feeding.[26]

Macrauchenia is thought to have probably lived in herds, as evidenced by the finding of at least 3 individuals preserved together at the Kamac Mayu site in Chile, with herding individuals probably moving in coordination. Macrauchenia is suggested to have concentrated on foraging in small areas before swiftly moving on to other feeding areas. It has been suggested that Macrauchenia engaged in long distance seasonal migrations in search of food.[24] Like living animals of similar size, it has been suggested that Macrauchenia probably only gave birth to a single offspring at a time.[31]

A 2020 study suggested that Macrauchenia was a capable and fast runner with fossilised footprints suggesting that its feet were held in a digitigrade stance, with the neck probably being held horizontally when running. The running style of Macrauchenia has been suggested to be similar to that of a saiga antelope or spotted hyenas, with a lack of flexing in the spine.[24] A 2005 study suggested that Macrauchenia may have been adapted to swerving as a strategy of avoiding predators, based on the strength of the limb bones.[32] The morphology of its hindlimbs suggests that they were adapted to rapidly accelerating, which may have been useful for both efficient locomotion and escaping predators.[24] Isotopic analysis suggests that Macrauchenia was regularly consumed as prey by the large sabertooth cat Smilodon populator.[33]

Relationship with humans and extinction

[edit]Macrauchenia became extinct as part of the end-Pleistocene extinction event at the end of the Late Pleistocene, around 12–10,000 years ago, along with most large (megafaunal) mammals native to the Americas. The extinctions followed the arrival of humans in the Americas,[34] which in South America occurred at least 14,500 years ago (as evidenced by Monte Verde II in Chile).[35] The causes of the extinction have long been controversial with human hunting and climatic change widely considered to be the most probable causes.[36]

Several potential instances of human interaction with Macrauchenia have been recorded. A left mandible collected from somewhere in the Pampas region in the 19th century in the collections of the Museum national d’Histoire naturelle in France has been suggested to display cut marks caused by human butchery, probably to extract the tongue.[37] At Arroyo Seco 2 near Tres Arroyos in the Pampas in Argentina, bones of Macrauchenia amongst those of other megafauna were found associated with human artifacts dating to approximately 14,782–11,142 calibrated years Before Present. While some megafauna remains at the site show clear evidence of exploitation, those of Macrauchenia do not, perhaps because post-depositional degradation of the bones may have erased cut marks.[38][39] At the El Guanaco site in the Argentinean Pampas, remains of Macrauchenia, alongside those of the glyptodont Doedicurus, horses, and rhea eggshells are associated with stone tools.[40]

At the Paso Otero 5 site in the Pampas of northeast Argentina, burned bones of Macrauchenia alongside those of numerous other extinct megafauna species are associated with Fishtail points (a type of knapped stone spear point common across South America at the end of the Pleistocene, suggested to be used to hunt large mammals[41]). The bones of the megafauna were probably deliberately burned as fuel. No cut marks are visible on the vast majority of bones at the site (with only one bone of a llama possibly displaying any butchery marks), which may be due to the burning degrading the bones.[42]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Püschel, Hans P; Shelley, Sarah L; Williamson, Thomas E; Perini, Fernando A; Wible, John R; Brusatte, Stephen L (2024-09-02). "A new dentition-based phylogeny of Litopterna (Mammalia: Placentalia) and 'archaic' South American ungulates". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 202 (1). doi:10.1093/zoolinnean/zlae095. ISSN 0024-4082.

- ^ Püschel, Hans P.; Martinelli, Agustín G. (December 2023). "More than 100 years of a mistake: on the anatomy of the atlas of the enigmatic Macrauchenia patachonica". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 142 (1): 16. Bibcode:2023SwJP..142...16P. doi:10.1186/s13358-023-00279-1. ISSN 1664-2376.

- ^ a b c d Croft, Darin A.; Gelfo, Javier N.; López, Guillermo M. (2020-05-30). "Splendid Innovation: The Extinct South American Native Ungulates". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 48 (1): 259–290. Bibcode:2020AREPS..48..259C. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-072619-060126. ISSN 0084-6597. S2CID 213737574.

- ^ Defler, Thomas (2019), "The Native Ungulates of South America (Condylarthra and Meridiungulata)", History of Terrestrial Mammals in South America, Topics in Geobiology, vol. 42, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 89–115, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98449-0_5, ISBN 978-3-319-98448-3, S2CID 91879648, retrieved 2024-01-30

- ^ a b Püschel, Hans P.; Alarcón-Muñoz, Jhonatan; Soto-Acuña, Sergio; Ugalde, Raúl; Shelley, Sarah L.; Brusatte, Stephen L. (June 2023). "Anatomy and phylogeny of a new small macraucheniid (Mammalia: Litopterna) from the Bahía Inglesa Formation (late Miocene), Atacama Region, Northern Chile". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 30 (2): 415–460. doi:10.1007/s10914-022-09646-0. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ a b c d de Oliveira, Karoliny; Araújo, Thaísa; Rotti, Alline; Mothé, Dimila; Rivals, Florent; Avilla, Leonardo S. (March 2020). "Fantastic beasts and what they ate: Revealing feeding habits and ecological niche of late Quaternary Macraucheniidae from South America". Quaternary Science Reviews. 231: 106178. Bibcode:2020QSRv..23106178D. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106178. S2CID 213795563.

- ^ Moyano, Silvana Rocio; Giannini, Norberto Pedro (November 2018). "Cranial characters associated with the proboscis postnatal-development in Tapirus (Perissodactyla: Tapiridae) and comparisons with other extant and fossil hoofed mammals". Zoologischer Anzeiger. 277: 143–147. Bibcode:2018ZooAn.277..143M. doi:10.1016/j.jcz.2018.08.005. hdl:11336/86349.

- ^ a b Souza Lobo, Leonardo; Lessa, Gisele; Cartelle, Cástor; and Romano, Pedro S. R. (September 2017). "Dental eruption sequence and hypsodonty index of a Pleistocene macraucheniid from the Brazilian Intertropical Region". Journal of Paleontology. 91 (5): 1083–1090. Bibcode:2017JPal...91.1083S. doi:10.1017/jpa.2017.54. ISSN 0022-3360.

- ^ Fernicola, Juan C., Vizcaino, Sergio F., & De Iuliis, Gerardo (2009). The fossil mammals collected by Charles Darwin in South America during his travels on board the HMS Beagle. Revista De La Asociación Geológica Argentina, 64(1), 147-159. Retrieved from https://revista.geologica.org.ar/raga/article/view/1339

- ^ Darwin, Charles (2001). Keynes, Richard D. (ed.). Charles Darwin's Beagle diary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 9780521003179. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ "Darwin Correspondence Project - Letter 238 — Darwin, C. R. to Henslow, J. S., Mar 1834". Archived from the original on 2009-01-16. Retrieved 2008-12-19.

- ^ Owen 1838, p. 35

- ^ Croft, Darin Andrew; Anaya, Federico; Auerbach, David; Garzione, Carmala; MacFadden, Bruce J. (September 2009). "New Data on Miocene Neotropical Provinciality from Cerdas, Bolivia". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 16 (3): 175–198. doi:10.1007/s10914-009-9115-0. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ a b Scherer, Carolina; Pitana, Vanessa; Ribeiro, Ana Maria (2009-12-28). "Proterotheriidae and Macraucheniidae (Litopterna, Mammalia) from the Pleistocene of Rio Grande do Sul State, Brazil" (PDF). Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia. 12 (3): 231–246. doi:10.4072/rbp.2009.3.06.

- ^ a b c d Croft, Darin A.; Gelfo, Javier N.; López, Guillermo M. (2020-05-30). "Splendid Innovation: The Extinct South American Native Ungulates". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 48 (1): 259–290. Bibcode:2020AREPS..48..259C. doi:10.1146/annurev-earth-072619-060126. ISSN 0084-6597. S2CID 213737574.

- ^ Westbury, M.; Baleka, S.; Barlow, A.; Hartmann, S.; Paijmans, J. L. A.; Kramarz, A.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Bond, M.; Gelfo, J. N.; Reguero, M. A.; López-Mendoza, P.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Rinderknecht, A.; Jones, W.; Mena, F.; Billet, G.; de Muizon, C.; Aguilar, J. L.; MacPhee, R. D. E.; Hofreiter, M. (2017-06-27). "A mitogenomic timetree for Darwin's enigmatic South American mammal Macrauchenia patachonica". Nature Communications. 8: 15951. Bibcode:2017NatCo...815951W. doi:10.1038/ncomms15951. PMC 5490259. PMID 28654082.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (27 June 2017). "DNA solves ancient animal riddle that Darwin couldn't". CNN. Retrieved 19 July 2024.

- ^ Welker, Frido; Collins, Matthew J.; Thomas, Jessica A.; Wadsley, Marc; Brace, Selina; Cappellini, Enrico; Turvey, Samuel T.; Reguero, Marcelo; Gelfo, Javier N.; Kramarz, Alejandro; Burger, Joachim; Thomas-Oates, Jane; Ashford, David A.; Ashton, Peter; Rowsell, Kerry; Porter, Duncan M.; Kessler, Benedikt; Fischer, Roman; Baessmann, Carsten; Kaspar, Stephanie; Olsen, Jesper V.; Kiley, Patrick; Elliott, James A.; Kelstrup, Christian D.; Mullin, Victoria; Hofreiter, Michael; Willerslev, Eske; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Orlando, Ludovic; Barnes, Ian & MacPhee, Ross D. E. (2015-03-18). "Ancient proteins resolve the evolutionary history of Darwin's South American ungulates". Nature. 522 (7554): 81–84. Bibcode:2015Natur.522...81W. doi:10.1038/nature14249. hdl:11336/14769. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 25799987. S2CID 4467386.

- ^ Buckley, Michael (2015-04-01). "Ancient collagen reveals evolutionary history of the endemic South American 'ungulates'". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1806): 20142671. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2671. PMC 4426609. PMID 25833851.

- ^ a b c d e Lobo, Leonardo Souza; Gelfo, Javier N.; de Azevedo, Sergio A. K. (2024-12-31). "The phylogeny of Macraucheniidae (Mammalia, Panperissodactyla, Litopterna) at the genus level". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 22 (1). Bibcode:2024JSPal..2264201L. doi:10.1080/14772019.2024.2364201. ISSN 1477-2019.

- ^ Freitas-Oliveira, Roniel; Lima-Ribeiro, Matheus; Faleiro, Frederico Valtuille; Jardim, Lucas; Terribile, Levi Carina (June 2024). "Temperature changes affected mammal dispersal during the Great American Biotic Interchange". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 31 (2). doi:10.1007/s10914-024-09717-4. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ Carrillo, Juan D.; Faurby, Søren; Silvestro, Daniele; Zizka, Alexander; Jaramillo, Carlos; Bacon, Christine D.; Antonelli, Alexandre (2020-10-20). "Disproportionate extinction of South American mammals drove the asymmetry of the Great American Biotic Interchange". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (42): 26281–26287. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11726281C. doi:10.1073/pnas.2009397117. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 7585031. PMID 33020313.

- ^ Defler, Thomas (2019), "The Native Ungulates of South America (Condylarthra and Meridiungulata)", History of Terrestrial Mammals in South America, Topics in Geobiology, vol. 42, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 89–115, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-98449-0_5, ISBN 978-3-319-98448-3, retrieved 2024-08-03

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Blanco, R. Ernesto; Jones, Washington W.; Yorio, Lara; Rinderknecht, Andrés (October 2021). "Macrauchenia patachonica Owen, 1838: Limb bones morphology, locomotory biomechanics, and paleobiological inferences". Geobios. 68: 61–70. Bibcode:2021Geobi..68...61B. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2021.04.006.

- ^ Forasiepi, Analía M.; MacPhee, Ross D. E.; Del Pino, Santiago Hernández; Schmidt, Gabriela I.; Amson, Eli; Grohé, Camille (2016-06-22). "Exceptional Skull of Huayqueriana (Mammalia, Litopterna, Macraucheniidae) From the Late Miocene of Argentina: Anatomy, Systematics, and Paleobiological Implications". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 404: 1–76. doi:10.1206/0003-0090-404.1.1. ISSN 0003-0090. S2CID 89219979.

- ^ a b c Blanco, R. Ernesto; Yorio, Lara; Montenegro, Felipe (2023-05-02). "Reconstruction of the cervical skeleton posture of the recently-extinct litoptern mammal Macrauchenia patachonica Owen, 1838". Palaeovertebrata. 46 (1): e1. doi:10.18563/pv.46.1.e1.

- ^ Dozo, María Teresa; Martínez, Gastón; Gelfo, Javier N. (2023), Dozo, María Teresa; Paulina-Carabajal, Ariana; Macrini, Thomas E.; Walsh, Stig (eds.), "Paleoneurology of Litopterna: Digital and Natural Endocranial Casts of Macraucheniidae", Paleoneurology of Amniotes, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 809–836, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-13983-3_21, ISBN 978-3-031-13982-6, retrieved 2024-10-13

- ^ Shockey BJ. 2001. "Specialized knee joints in some extinct, endemic, South American herbivores" Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 46:277–88

- ^ de Oliveira, Karoliny; Asevedo, Lidiane; Calegari, Marcia R.; Gelfo, Javier N.; Mothé, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo (August 2021). "From oral pathology to feeding ecology: The first dental calculus paleodiet study of a South American native megamammal". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 109: 103281. Bibcode:2021JSAES.10903281D. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2021.103281.

- ^ Croft, Darin A.; Lorente, Malena (2021-08-17). Smith, Thierry (ed.). "No evidence for parallel evolution of cursorial limb adaptations among Neogene South American native ungulates (SANUs)". PLOS ONE. 16 (8): e0256371. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0256371. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 8370646. PMID 34403434.

- ^ Andrea, Elissamburu (July 2016). "Prediction of offspring in extant and extinct mammals to add light on paleoecology and evolution". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 453: 73–79. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.033. hdl:11336/54314.

- ^ R.A. Fariña, R.E. Blanco, P. Christiansen "Swerving as the escape strategy of Macrauchenia patachonica Owen (Mammalia; Litopterna)" Ameghiniana, 42 (2005), pp. 751-760

- ^ Bocherens, Hervé; Cotte, Martin; Bonini, Ricardo; Scian, Daniel; Straccia, Pablo; Soibelzon, Leopoldo; Prevosti, Francisco J. (May 2016). "Paleobiology of sabretooth cat Smilodon populator in the Pampean Region (Buenos Aires Province, Argentina) around the Last Glacial Maximum: Insights from carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes in bone collagen". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 449: 463–474. Bibcode:2016PPP...449..463B. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.02.017. hdl:11336/43965.

- ^ Prado, José L.; Martinez-Maza, Cayetana; Alberdi, María T. (May 2015). "Megafauna extinction in South America: A new chronology for the Argentine Pampas". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 425: 41–49. Bibcode:2015PPP...425...41P. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2015.02.026.

- ^ Pino, Mario; Dillehay, Tom D. (June 2023). "Monte Verde II: an assessment of new radiocarbon dates and their sedimentological context". Antiquity. 97 (393): 524–540. doi:10.15184/aqy.2023.32. ISSN 0003-598X.

- ^ Cione, Alberto; Tonni, Eduardo; Soilbenzon, Leopoldo (2003). "The Broken Zig-Zag: Late Cenozoic large mammal and tortoise extinction in South America" (PDF). Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 5: 1–19. doi:10.22179/REVMACN.5.26.

- ^ Toledo, Marcelo Javier (April 2023). "Anthropic modifications on megafauna bones in the paleontological collections of the Museum national d'Histoire naturelle de Paris: Historical aspects and implications for the Pampean Pleistocene peopling". L'Anthropologie. 127 (2): 103134. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2023.103134.

- ^ Bampi, Hugo; Barberi, Maira; Lima-Ribeiro, Matheus S. (December 2022). "Megafauna kill sites in South America: A critical review". Quaternary Science Reviews. 298: 107851. Bibcode:2022QSRv..29807851B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2022.107851. S2CID 253876769.

- ^ Politis, Gustavo G.; Gutiérrez, María A.; Rafuse, Daniel J.; Blasi, Adriana (2016-09-28). Petraglia, Michael D. (ed.). "The Arrival of Homo sapiens into the Southern Cone at 14,000 Years Ago". PLOS ONE. 11 (9): e0162870. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1162870P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0162870. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5040268. PMID 27683248.

- ^ Bonnat, Gustavo Federico (2024), Bonnat, Gustavo Federico; Álvarez, María Clara; Mazzanti, Diana Leonis; Barros, María Paula (eds.), "Lithic Procurement, Mobility, and Social Interaction in Early Hunter-Gatherer Societies (⁓12,000 Cal. Years BP) in the Humid Pampas Sub-region, Buenos Aires, Argentina", Current Research in Archaeology of South American Pampas, Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 129–165, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-55194-9_6, ISBN 978-3-031-55193-2, retrieved 2024-10-23

- ^ Prates, Luciano; Rivero, Diego; Perez, S. Ivan (2022-10-25). "Changes in projectile design and size of prey reveal the central role of Fishtail points in megafauna hunting in South America". Scientific Reports. 12 (1): 16964. Bibcode:2022NatSR..1216964P. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-21287-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 9596454. PMID 36284118.

- ^ G. Martínez, M. A. Gutiérrez, Paso Otero 5: A summary of the interdisciplinary lines of evidence for reconstructing early human occupation and paleoenvironment in the Pampean region, Argentina, in Peuplements et Préhistoire de l’Amérique, D. Vialou, Ed. (Muséum National d’ Histoire Naturelle. Departement de Prehistoire, U.M.R, Paris, 2011), pp. 271–284.

- Owen, Richard (1838). "Description of Parts of the Skeleton of Macrauchenia patachonica". In Darwin, C. R. (ed.). Fossil Mammalia Part 1 No. 1. The zoology of the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle. London: Smith Elder and Co.

- Macraucheniids

- Messinian first appearances

- Holocene extinctions

- Miocene mammals of South America

- Pliocene mammals of South America

- Pleistocene mammals of South America

- Lujanian

- Ensenadan

- Uquian

- Chapadmalalan

- Montehermosan

- Huayquerian

- Neogene Argentina

- Cerro Azul Formation

- Pleistocene Argentina

- Pleistocene Bolivia

- Pleistocene Brazil

- Pleistocene Chile

- Pleistocene Paraguay

- Pleistocene Peru

- Dolores Formation, Uruguay

- Pleistocene Venezuela

- Fossils of Argentina

- Fossils of Bolivia

- Fossils of Brazil

- Fossils of Chile

- Fossils of Paraguay

- Fossils of Peru

- Fossils of Uruguay

- Fossils of Venezuela

- Fossil taxa described in 1838

- Taxa named by Richard Owen

- Prehistoric placental genera

- Sopas Formation