Simple machine

| History of technology |

|---|

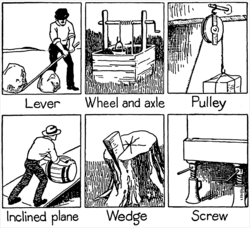

A simple machine is a mechanical device that changes the direction or magnitude of a force.[1] In general, they can be defined as the simplest mechanisms that use mechanical advantage (also called leverage) to multiply force.[2] Usually the term refers to the six classical simple machines that were defined by Renaissance scientists:[3][4][5]

A simple machine uses a single applied force to do work against a single load force. Ignoring friction losses, the work done on the load is equal to the work done by the applied force. The machine can increase the amount of the output force, at the cost of a proportional decrease in the distance moved by the load. The ratio of the output to the applied force is called the mechanical advantage.

Simple machines can be regarded as the elementary "building blocks" of which all more complicated machines (sometimes called "compound machines"[6][7]) are composed.[2][8] For example, wheels, levers, and pulleys are all used in the mechanism of a bicycle.[9][10] The mechanical advantage of a compound machine is just the product of the mechanical advantages of the simple machines of which it is composed.

Although they continue to be of great importance in mechanics and applied science, modern mechanics has moved beyond the view of the simple machines as the ultimate building blocks of which all machines are composed, which arose in the Renaissance as a neoclassical amplification of ancient Greek texts. The great variety and sophistication of modern machine linkages, which arose during the Industrial Revolution, is inadequately described by these six simple categories. Various post-Renaissance authors have compiled expanded lists of "simple machines", often using terms like basic machines,[9] compound machines,[6] or machine elements to distinguish them from the classical simple machines above. By the late 1800s, Franz Reuleaux[11] had identified hundreds of machine elements, calling them simple machines.[12] Modern machine theory analyzes machines as kinematic chains composed of elementary linkages called kinematic pairs.

History

The idea of a simple machine originated with the Greek philosopher Archimedes around the 3rd century BC, who studied the Archimedean simple machines: lever, pulley, and screw.[2][13] He discovered the principle of mechanical advantage in the lever.[14] Archimedes' famous remark with regard to the lever: "Give me a place to stand on, and I will move the Earth," (Greek: δῶς μοι πᾶ στῶ καὶ τὰν γᾶν κινάσω)[15] expresses his realization that there was no limit to the amount of force amplification that could be achieved by using mechanical advantage. Later Greek philosophers defined the classic five simple machines (excluding the inclined plane) and were able to calculate their (ideal) mechanical advantage.[7] For example, Heron of Alexandria (c. 10–75 AD) in his work Mechanics lists five mechanisms that can "set a load in motion": lever, windlass, pulley, wedge, and screw,[13] and describes their fabrication and uses.[16] However the Greeks' understanding was limited to the statics of simple machines (the balance of forces), and did not include dynamics, the tradeoff between force and distance, or the concept of work.

During the Renaissance the dynamics of the mechanical powers, as the simple machines were called, began to be studied from the standpoint of how far they could lift a load, in addition to the force they could apply, leading eventually to the new concept of mechanical work. In 1586 Flemish engineer Simon Stevin derived the mechanical advantage of the inclined plane, and it was included with the other simple machines. The complete dynamic theory of simple machines was worked out by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei in 1600 in Le Meccaniche (On Mechanics), in which he showed the underlying mathematical similarity of the machines as force amplifiers.[17][18] He was the first to explain that simple machines do not create energy, only transform it.[17]

The classic rules of sliding friction in machines were discovered by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), but were unpublished and merely documented in his notebooks, and were based on pre-Newtonian science such as believing friction was an ethereal fluid. They were rediscovered by Guillaume Amontons (1699) and were further developed by Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (1785).[19]

Ideal simple machine

If a simple machine does not dissipate energy through friction, wear or deformation, then energy is conserved and it is called an ideal simple machine. In this case, the power into the machine equals the power out, and the mechanical advantage can be calculated from its geometric dimensions.

Although each machine works differently mechanically, the way they function is similar mathematically.[20] In each machine, a force is applied to the device at one point, and it does work moving a load at another point.[21] Although some machines only change the direction of the force, such as a stationary pulley, most machines multiply the magnitude of the force by a factor, the mechanical advantage

that can be calculated from the machine's geometry and friction.

Simple machines do not contain a source of energy,[22] so they cannot do more work than they receive from the input force.[21] A simple machine with no friction or elasticity is called an ideal machine.[23][24][25] Due to conservation of energy, in an ideal simple machine, the power output (rate of energy output) at any time is equal to the power input

The power output equals the velocity of the load multiplied by the load force . Similarly the power input from the applied force is equal to the velocity of the input point multiplied by the applied force . Therefore,

So the mechanical advantage of an ideal machine is equal to the velocity ratio, the ratio of input velocity to output velocity

The velocity ratio is also equal to the ratio of the distances covered in any given period of time[26][27][28]

Therefore, the mechanical advantage of an ideal machine is also equal to the distance ratio, the ratio of input distance moved to output distance moved

This can be calculated from the geometry of the machine. For example, the mechanical advantage and distance ratio of the lever is equal to the ratio of its lever arms.

The mechanical advantage can be greater or less than one:

- If , the output force is greater than the input, the machine acts as a force amplifier, but the distance moved by the load is less than the distance moved by the input force .

- If , the output force is less than the input, but the distance moved by the load is greater than the distance moved by the input force.

In the screw, which uses rotational motion, the input force should be replaced by the torque, and the velocity by the angular velocity the shaft is turned.

Friction and efficiency

All real machines have friction, which causes some of the input power to be dissipated as heat. If is the power lost to friction, from conservation of energy

The mechanical efficiency of a machine (where ) is defined as the ratio of power out to the power in, and is a measure of the frictional energy losses

As above, the power is equal to the product of force and velocity, so

Therefore,

So in non-ideal machines, the mechanical advantage is always less than the velocity ratio by the product with the efficiency . So a machine that includes friction will not be able to move as large a load as a corresponding ideal machine using the same input force.

Compound machines

A compound machine is a machine formed from a set of simple machines connected in series with the output force of one providing the input force to the next. For example, a bench vise consists of a lever (the vise's handle) in series with a screw, and a simple gear train consists of a number of gears (wheels and axles) connected in series.

The mechanical advantage of a compound machine is the ratio of the output force exerted by the last machine in the series divided by the input force applied to the first machine, that is

Because the output force of each machine is the input of the next, , this mechanical advantage is also given by

Thus, the mechanical advantage of the compound machine is equal to the product of the mechanical advantages of the series of simple machines that form it

Similarly, the efficiency of a compound machine is also the product of the efficiencies of the series of simple machines that form it

Self-locking machines

In many simple machines, if the load force on the machine is high enough in relation to the input force , the machine will move backwards, with the load force doing work on the input force.[29] So these machines can be used in either direction, with the driving force applied to either input point. For example, if the load force on a lever is high enough, the lever will move backwards, moving the input arm backwards against the input force. These are called reversible, non-locking or overhauling machines, and the backward motion is called overhauling.

However, in some machines, if the frictional forces are high enough, no amount of load force can move it backwards, even if the input force is zero. This is called a self-locking, nonreversible, or non-overhauling machine.[29] These machines can only be set in motion by a force at the input, and when the input force is removed will remain motionless, "locked" by friction at whatever position they were left.

Self-locking occurs mainly in those machines with large areas of sliding contact between moving parts: the screw, inclined plane, and wedge:

- The most common example is a screw. In most screws, one can move the screw forward or backward by turning it, and one can move the nut along the shaft by turning it, but no amount of pushing the screw or the nut will cause either of them to turn.

- On an inclined plane, a load can be pulled up the plane by a sideways input force, but if the plane is not too steep and there is enough friction between load and plane, when the input force is removed the load will remain motionless and will not slide down the plane, regardless of its weight.

- A wedge can be driven into a block of wood by force on the end, such as from hitting it with a sledge hammer, forcing the sides apart, but no amount of compression force from the wood walls will cause it to pop back out of the block.

A machine will be self-locking if and only if its efficiency is below 50%:[29]

Whether a machine is self-locking depends on both the friction forces (coefficient of static friction) between its parts, and the distance ratio (ideal mechanical advantage). If both the friction and ideal mechanical advantage are high enough, it will self-lock.

Proof

When a machine moves in the forward direction from point 1 to point 2, with the input force doing work on a load force, from conservation of energy[30][31] the input work is equal to the sum of the work done on the load force and the work lost to friction

| Eq. 1 |

If the efficiency is below 50% ():

From Eq. 1

When the machine moves backward from point 2 to point 1 with the load force doing work on the input force, the work lost to friction is the same

So the output work is

Thus the machine self-locks, because the work dissipated in friction is greater than the work done by the load force moving it backwards even with no input force.

Modern machine theory

Machines are studied as mechanical systems consisting of actuators and mechanisms that transmit forces and movement, monitored by sensors and controllers. The components of actuators and mechanisms consist of links and joints that form kinematic chains.

Kinematic chains

Simple machines are elementary examples of kinematic chains that are used to model mechanical systems ranging from the steam engine to robot manipulators. The bearings that form the fulcrum of a lever and that allow the wheel and axle and pulleys to rotate are examples of a kinematic pair called a hinged joint. Similarly, the flat surface of an inclined plane and wedge are examples of the kinematic pair called a sliding joint. The screw is usually identified as its own kinematic pair called a helical joint.

Two levers, or cranks, are combined into a planar four-bar linkage by attaching a link that connects the output of one crank to the input of another. Additional links can be attached to form a six-bar linkage or in series to form a robot.[24]

Classification of machines

The identification of simple machines arises from a desire for a systematic method to invent new machines. Therefore, an important concern is how simple machines are combined to make more complex machines. One approach is to attach simple machines in series to obtain compound machines.

However, a more successful strategy was identified by Franz Reuleaux, who collected and studied over 800 elementary machines. He realized that a lever, pulley, and wheel and axle are in essence the same device: a body rotating about a hinge. Similarly, an inclined plane, wedge, and screw are a block sliding on a flat surface.[32]

This realization shows that it is the joints, or the connections that provide movement, that are the primary elements of a machine. Starting with four types of joints, the revolute joint, sliding joint, cam joint and gear joint, and related connections such as cables and belts, it is possible to understand a machine as an assembly of solid parts that connect these joints.[24]

Kinematic synthesis

The design of mechanisms to perform required movement and force transmission is known as kinematic synthesis. This is a collection of geometric techniques for the mechanical design of linkages, cam and follower mechanisms and gears and gear trains.

See also

- Linkage (mechanical)

- Cam and follower mechanisms

- Gears and gear trains

- Mechanism (engineering)

- Rolamite, the only elementary machine discovered in the 20th century

References

- ^ Paul, Akshoy; Roy, Pijush; Mukherjee, Sanchayan (2005), Mechanical sciences: engineering mechanics and strength of materials, Prentice Hall of India, p. 215, ISBN 978-81-203-2611-8.

- ^ a b c Asimov, Isaac (1988), Understanding Physics, New York: Barnes & Noble, p. 88, ISBN 978-0-88029-251-1.

- ^ Anderson, William Ballantyne (1914). Physics for Technical Students: Mechanics and Heat. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 112. Retrieved May 11, 2008.

- ^ "Mechanics". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3. John Donaldson. 1773. p. 44. Retrieved April 5, 2020.

- ^ Morris, Christopher G. (1992). Academic Press Dictionary of Science and Technology. Gulf Professional Publishing. p. 1993. ISBN 978-0122004001.

- ^ a b Compound machines, University of Virginia Physics Department, retrieved June 11, 2010.

- ^ a b Usher, Abbott Payson (1988). A History of Mechanical Inventions. US: Courier Dover Publications. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-486-25593-4.

- ^ Wallenstein, Andrew (June 2002). "Foundations of cognitive support: Toward abstract patterns of usefulness". Proceedings of the 9th Annual Workshop on the Design, Specification, and Verification of Interactive Systems. Springer. p. 136. ISBN 978-3540002666. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Prater, Edward L. (1994), Basic machines (PDF), U.S. Navy Naval Education and Training Professional Development and Technology Center, NAVEDTRA 14037.

- ^ Reuleaux, F. (1963) [1876], The kinematics of machinery (translated and annotated by A.B.W. Kennedy), New York: reprinted by Dover.

- ^ Cornell University, Reuleaux Collection of Mechanisms and Machines at Cornell University, Cornell University.

- ^ a b Chiu, Y. C. (2010), An introduction to the History of Project Management, Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers, p. 42, ISBN 978-90-5972-437-2

- ^ Ostdiek, Vern; Bord, Donald (2005). Inquiry into Physics. Thompson Brooks/Cole. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-534-49168-0. Retrieved May 22, 2008.

- ^ Quoted by Pappus of Alexandria in Synagoge, Book VIII

- ^ Strizhak, Viktor; Igor Penkov; Toivo Pappel (2004). "Evolution of design, use, and strength calculations of screw threads and threaded joints". HMM2004 International Symposium on History of Machines and Mechanisms. Kluwer Academic. p. 245. ISBN 1-4020-2203-4. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Krebs, Robert E. (2004). Groundbreaking Experiments, Inventions, and Discoveries of the Middle Ages. Greenwood. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-313-32433-8. Retrieved May 21, 2008.

- ^ Stephen, Donald; Lowell Cardwell (2001). Wheels, clocks, and rockets: a history of technology. US: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 85–87. ISBN 978-0-393-32175-3.

- ^ Armstrong-Hélouvry, Brian (1991). Control of machines with friction. Springer. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7923-9133-3.

- ^ This fundamental insight was the subject of Galileo Galilei's 1600 work Le Meccaniche (On Mechanics).

- ^ a b Bhatnagar, V. P. (1996). A Complete Course in Certificate Physics. India: Pitambar. pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-81-209-0868-0.

- ^ Simmons, Ron; Cindy, Barden (2008). Discover! Work & Machines. US: Milliken. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-4291-0947-5.

- ^ Gujral, I. S. (2005). Engineering Mechanics. Firewall Media. pp. 378–380. ISBN 978-81-7008-636-9.

- ^ a b c Uicker, John J. Jr.; Pennock, Gordon R.; Shigley, Joseph E. (2003), Theory of Machines and Mechanisms (third ed.), New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-515598-3

- ^ Paul, Burton (1979). Kinematics and Dynamics of Planar Machinery. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-516062-6.

- ^ Rao, S.; Durgaiah, R. (2005). Engineering Mechanics. Universities Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-81-7371-543-3.

- ^ Goyal, M. C.; Raghuvanshee, G. S. (2011). Engineering Mechanics. PHI Learning. p. 212. ISBN 978-81-203-4327-6.

- ^ Avison, John (2014). The World of Physics. Nelson Thornes. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-17-438733-6.

- ^ a b c Gujral, I. S. (2005). Engineering Mechanics. Firewall Media. p. 382. ISBN 978-81-7008-636-9.

- ^ Rao, S.; Durgaiah, R. (2005). Engineering Mechanics. Universities Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-81-7371-543-3.

- ^ Goyal, M. C.; Raghuvanshi, G. S. (2009). Engineering Mechanics. New Delhi: PHI Learning Private Ltd. p. 202. ISBN 978-81-203-3789-3.

- ^ Hartenberg, R.S. & J. Denavit (1964) Kinematic synthesis of linkages, New York: McGraw-Hill, online link from Cornell University.