MMR vaccine

MMR vaccine | |

| Combination of | |

|---|---|

| Measles vaccine | Vaccine |

| Mumps vaccine | Vaccine |

| Rubella vaccine | Vaccine |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | M-M-R II, Priorix, Tresivac, others |

| Other names | MPR vaccine[1] |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601176 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| | |

The MMR vaccine is a vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella (German measles), abbreviated as MMR.[6] The first dose is generally given to children around 9 months to 15 months of age, with a second dose at 15 months to 6 years of age, with at least four weeks between the doses.[7][8][9] After two doses, 97% of people are protected against measles, 88% against mumps, and at least 97% against rubella.[7] The vaccine is also recommended for those who do not have evidence of immunity,[7] those with well-controlled HIV/AIDS,[10][11] and within 72 hours of exposure to measles among those who are incompletely immunized.[8] It is given by injection.[12]

The MMR vaccine is widely used around the world. As of 2012, 575 million doses had been administered since the vaccine's introduction worldwide.[13] Measles resulted in 2.6 million deaths per year before immunization became common.[13] This has decreased to 122,000 deaths per year as of 2012,[update] mostly in low-income countries.[13] Through vaccination, as of 2018[update], rates of measles in North and South America are very low.[13] Rates of disease have been seen to increase in populations that go unvaccinated.[13] Between 2000 and 2018, vaccination decreased measles deaths by 73%.[14]

Side effects of immunization are generally mild and resolve without any specific treatment.[15] These may include fever, as well as pain or redness at the injection site.[15] Severe allergic reactions occur in about one in a million people.[15] Because it contains live viruses, the MMR vaccine is not recommended during pregnancy but may be given during breastfeeding.[7] The vaccine is safe to give at the same time as other vaccines.[15] Being recently immunized does not increase the risk of passing measles, mumps, or rubella on to others.[7] There is no evidence of an association between MMR immunisation and autistic spectrum disorders.[16][17][18] The MMR vaccine is a mixture of live weakened viruses of the three diseases.[7]

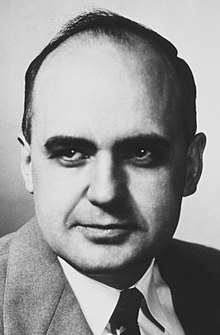

The MMR vaccine was developed by Maurice Hilleman.[6] It was licensed for use in the US by Merck in 1971.[19] Stand-alone measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines had been previously licensed in 1963, 1967, and 1969, respectively.[19][20] Recommendations for a second dose were introduced in 1989.[19] The MMRV vaccine, which also covers chickenpox, may be used instead.[7] An MR vaccine, without coverage for mumps, is also occasionally used.[21]

Medical use

[edit]

Cochrane concluded that the "Existing evidence on the safety and effectiveness of MMR and MMRV vaccine supports current policies of mass immunisation aimed at global measles eradication to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with measles mumps rubella and varicella."[16]

The combined MMR vaccine induces immunity less painfully than three separate injections at the same time, and sooner and more efficiently than three injections given on different dates. Public Health England reports that providing a single combined vaccine as of 1988, rather than giving the option to have them also done separately, increased uptake of the vaccine.[22]

Measles

[edit]

Before the widespread use of a vaccine against measles, rates of disease were so high that infection was felt to be "as inevitable as death and taxes."[23] Reported cases of measles in the United States fell from hundreds of thousands to tens of thousands per year following introduction of the vaccine in 1963. Increasing uptake of the vaccine following outbreaks in 1971, and 1977, brought this down to thousands of cases per year in the 1980s. An outbreak of almost 30,000 cases in 1990 led to a renewed push for vaccination and the addition of a second vaccine to the recommended schedule. Fewer than 200 cases have been reported in the US each year between 1997 and 2013, and the disease is no longer considered endemic there.[24][25][26]

The benefit of measles vaccination in preventing illness, disability, and death has been well documented. The first 20 years of licensed measles vaccination in the US prevented an estimated 52 million cases of the disease, 17,400 cases of intellectual disability, and 5,200 deaths.[27] During 1999–2004, a strategy led by the World Health Organization and UNICEF led to improvements in measles vaccination coverage that averted an estimated 1.4 million measles deaths worldwide.[28] Between 2000 and 2018, measles vaccination resulted in a 73% decrease in deaths from the disease.[14]

Measles is common in many areas of the world. Although it was declared eliminated from the US in 2000, high rates of vaccination and good communication with people who refuse vaccination are needed to prevent outbreaks and sustain the elimination of measles in the US.[29] Of the 66 cases of measles reported in the US in 2005, slightly over half were attributable to one unvaccinated individual who acquired measles during a visit to Romania.[30] This individual returned to a community with many unvaccinated children. The resulting outbreak infected 34 people, mostly children and virtually all unvaccinated; 9% were hospitalized, and the cost of containing the outbreak was estimated at $167,685. A major epidemic was averted due to high rates of vaccination in the surrounding communities.[29]

In 2017, an outbreak of measles occurred among the Somali-American community in Minnesota, where MMR vaccination rates had declined due to the misconception that the vaccine could cause autism. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded 65 affected children in the outbreak by April 2017.[31]

Rubella

[edit]

Rubella, also known as German measles, was also very common before widespread vaccination. The major risk of rubella is during pregnancy when the baby may contract congenital rubella, which can cause significant congenital defects.[32]

Mumps

[edit]Mumps is another viral disease that was once very common, especially during childhood. If mumps is acquired by a male who is past puberty, a possible complication is bilateral orchitis, which can in some cases lead to sterility.[33]

Administration

[edit]The MMR vaccine is administered by a subcutaneous injection, the first dose typically at twelve months of age.[12] The second dose may be given as early as one month after the first dose.[34] The second dose is a dose to produce immunity in the small number of persons (2–5%) who fail to develop measles immunity after the first dose. In the US it is done before entry to kindergarten because that is a convenient time.[35] Areas where measles is common typically recommend the first dose at nine months of age and the second dose at fifteen months of age.[8]

Safety

[edit]Adverse reactions, rarely serious, may occur from each component of the MMR vaccine. Ten percent of children develop fever, malaise, and a rash 5–21 days after the first vaccination;[36] and 3% develop joint pain lasting 18 days on average.[37] Older women appear to be more at risk of joint pain, acute arthritis, and even (rarely) chronic arthritis.[38] Anaphylaxis is an extremely rare but serious allergic reaction to the vaccine.[39] One cause can be egg allergy.[40] In 2014, the FDA approved two additional possible adverse events on the vaccination label: acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), and transverse myelitis, with permission to also add "difficulty walking" to the package inserts.[41] A 2012 IOM report found that the measles component of the MMR vaccine can cause measles inclusion body encephalitis in immunocompromised individuals. This report also rejected any connection between the MMR vaccine and autism.[42] Some versions of the vaccine contain the antibiotic neomycin and therefore should not be used in people allergic to this antibiotic.[18]

The number of reports on neurological disorders is very small, other than evidence for an association between a form of the MMR vaccine containing the Urabe mumps strain and rare adverse events of aseptic meningitis, a form of viral meningitis.[38][43] The UK National Health Service stopped using the Urabe mumps strain in the early 1990s due to cases of transient mild viral meningitis, and switched to a form using the Jeryl Lynn mumps strain instead.[44] The Urabe strain remains in use in a number of countries; MMR with the Urabe strain is much cheaper to manufacture than with the Jeryl Lynn strain,[45] and a strain with higher efficacy along with a somewhat higher rate of mild side effects may still have the advantage of reduced incidence of overall adverse events.[44]

A Cochrane review found that, compared with placebo, MMR vaccine was associated with fewer upper respiratory tract infections, more irritability, and a similar number of other adverse effects.[16]

Naturally acquired measles often occurs with immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP, a purpuric rash and an increased tendency to bleed that resolves within two months in children), occurring in 1 to 20,000 cases.[16] Approximately 1 in 40,000 children are thought to acquire ITP in the six weeks following an MMR vaccination.[16] ITP below the age of six years is generally a mild disease, rarely having long-term consequences.[46][47]

False claims about autism

[edit]In 1998 Andrew Wakefield et al. published a fraudulent paper about twelve children, reportedly with bowel symptoms and autism or other disorders acquired soon after administration of MMR vaccine,[48] while supporting a competing vaccine. In 2010, Wakefield's research was found by the General Medical Council to have been "dishonest",[49] and The Lancet fully retracted the paper.[50][51] Three months following The Lancet's retraction, Wakefield was struck off the UK medical register, with a statement identifying deliberate falsification in the research published in The Lancet,[52] and was barred from practising medicine in the UK.[53] The research was declared fraudulent in 2011 by the British Medical Journal.[54]

Since Wakefield's publication, multiple peer-reviewed studies have failed to show any association between the vaccine and autism.[16][55] The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,[56][57] the Institute of Medicine of the US National Academy of Sciences,[58] the UK National Health Service[59] and the Cochrane Library review[16] have all concluded that there is no evidence of a link.

Administering the vaccines in three separate doses does not reduce the chance of adverse effects, and it increases the opportunity for infection by the two diseases not immunized against first.[55][60] Health experts have criticized media reporting of the MMR-autism controversy for triggering a decline in vaccination rates.[61] Before publication of Wakefield's article, the inoculation rate for MMR in the UK was 92%; after publication, the rate dropped to below 80%. In 1998, there were 56 measles cases in the UK; by 2008, there were 1348 cases, with two confirmed deaths.[62]

In Japan, the MMR triplet is not used. Immunity is achieved by a combination vaccine for measles and rubella, followed up later with a mumps only vaccine. This has had no effect on autism rates in the country, further disproving the MMR autism hypothesis.[63]

History

[edit]

The component viral strains of MMR vaccine were developed by propagation in animal and human cells.[64]

For example, in the case of mumps and measles viruses, the virus strains were grown in embryonated chicken eggs. This produced strains of virus which were adapted for chicken cells and less well-suited for human cells. These strains are therefore called attenuated strains. They are sometimes referred to as neuroattenuated because these strains are less virulent to human neurons than the wild strains.

The rubella component, Meruvax, was developed in 1967, through propagation using the human embryonic lung cell line WI-38 (named for the Wistar Institute) that was derived six years earlier in 1961.[65][66]

| Disease immunized | Component vaccine | Virus strain | Propagation medium | Growth medium |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measles | Attenuvax | Enders' attenuated Edmonston strain[67] | chick embryo cell culture | Medium 199 |

| Mumps | Mumpsvax[68] | Jeryl Lynn (B level) strain[69] | ||

| Rubella | Meruvax II | Wistar RA 27/3 strain of live attenuated rubella virus | WI-38 human embryonic cell line | MEM (solution containing buffered salts, fetal bovine serum, human serum albumin and neomycin, etc.) |

The term "MPR vaccine" is also used to refer to this vaccine, whereas "P" refers to parotitis which is caused by mumps.[1]

Merck MMR II is supplied freeze-dried (lyophilized) and contains live viruses. Before injection, it is reconstituted with the solvent provided.[70]

According to a review published in 2018, the GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) MMR vaccine known as Pluserix "contains the Schwarz measles virus, the Jeryl Lynn–like mumps strain, and RA27/3 rubella virus".[71]

Pluserix was introduced in Hungary in 1999.[72] Enders' Edmonston strain has been used since 1999 in Hungary in Merck MMR II product.[72] GSK Priorix vaccine, which uses attenuated Schwarz Measles, was introduced in Hungary in 2003.[72]

MMRV vaccine

[edit]The MMRV vaccine, a combined measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, has been proposed as a replacement for the MMR vaccine to simplify the administration of the vaccines.[34] Preliminary data indicate a rate of febrile seizures of 9 per 10,000 vaccinations with MMRV, as opposed to 4 per 10,000 for separate MMR and varicella shots; US health officials therefore, do not express a preference for use of MMRV vaccine over separate injections.[73]

In a 2012 study[74] pediatricians and family doctors were sent a survey to gauge their awareness of the increased risk of febrile seizures (fever fits) in the MMRV. 74% of family doctors and 29% of pediatricians were unaware of the increased risk of febrile seizures. After reading an informational statement only 7% of family doctors and 20% of pediatricians would recommend the MMRV for a healthy 12- to 15-month-old child. The factor that was reported as the "most important" deciding factor in recommending the MMRV over the MMR+V was ACIP/AAFP/AAP recommendations (pediatricians, 77%; family physicians, 73%).

MR vaccine

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (November 2022) |

This is a vaccine that covers measles and rubella but not mumps.[21] As of 2014, it was used in a "few (unidentified) countries".[21]

Society and culture

[edit]Religious concerns

[edit]Some brands of the vaccine use gelatin, derived from pigs, as a stabilizer.[75] This has caused reduced take-up among some communities,[75][76] despite the fact that alternative vaccines without pig derivatives are approved and available.[75]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Grignolio A (2018). Vaccines: Are they Worth a Shot?. Springer. p. 2. ISBN 9783319681061. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2020.

- ^ "Measles virus vaccine / mumps virus vaccine / rubella virus vaccine (M-M-R II) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 16 October 2019. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ "M-M-R II- measles, mumps, and rubella virus vaccine live injection, powder, lyophilized, for suspension". DailyMed. 23 May 2022. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "Priorix- measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine, live kit". DailyMed. 3 June 2022. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 19 June 2022.

- ^ "M-M-RVaxPro EPAR". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- ^ a b "Maurice R. Hilleman, PhD, DSc". Seminars in Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 16 (3): 225–226. July 2005. doi:10.1053/j.spid.2005.05.002. PMID 16044396.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 26 April 2020.

- ^ a b c "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2017". Relevé Épidémiologique Hebdomadaire. 92 (17): 205–227. April 2017. hdl:10665/255149. PMID 28459148.

- ^ World Health Organization (January 2019). "Measles vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2017 - Recommendations". Vaccine. 37 (2): 219–222. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.066. PMID 28760612. S2CID 205605355.

- ^ Kinney R (2 May 2017). "Core Concepts – Immunizations in Adults – Basic HIV Primary Care – National HIV CurriculumImmunizations in Adults". www.hiv.uw.edu. Archived from the original on 2 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Watson JC, Hadler SC, Dykewicz CA, Reef S, Phillips L (May 1998). "Measles, mumps, and rubella--vaccine use and strategies for elimination of measles, rubella, and congenital rubella syndrome and control of mumps: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)" (PDF). MMWR. Recommendations and Reports. 47 (RR-8): 1–57. PMID 9639369. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Administering MMR Vaccine". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Addressing misconceptions on measles vaccination". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 15 April 2014. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ a b "Measles Fact Sheet". World Health Organization (WHO). 5 December 2019. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d "MMR (Measles, Mumps, and Rubella) Vaccine Information Statement". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). August 2021. Archived from the original on 3 September 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Di Pietrantonj C, Rivetti A, Marchione P, Debalini MG, Demicheli V (November 2021). "Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (11): CD004407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5. PMC 8607336. PMID 34806766.

- ^ Hussain A, Ali S, Ahmed M, Hussain S (July 2018). "The Anti-vaccination Movement: A Regression in Modern Medicine". Cureus. 10 (7): e2919. doi:10.7759/cureus.2919. PMC 6122668. PMID 30186724.

- ^ a b Spencer JP, Trondsen Pawlowski RH, Thomas S (June 2017). "Vaccine Adverse Events: Separating Myth from Reality". American Family Physician. 95 (12): 786–794. PMID 28671426.

- ^ a b c Goodson JL, Seward JF (December 2015). "Measles 50 Years After Use of Measles Vaccine". Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. 29 (4): 725–743. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.08.001. PMID 26610423.

- ^ "Measles: information about the disease and vaccines Questions and Answers" (PDF). Immunization Action Coalition. November 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ a b c "Information Sheet Observed Rate of Vaccine Reactions, Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Vaccines" (PDF). fdaghana.gov.gh. May 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR): use of combined vaccine instead of single vaccines". GOV.UK. Archived from the original on 12 July 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Babbott FL, Gordon JE (September 1954). "Modern measles". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 228 (3): 334–361. doi:10.1097/00000441-195409000-00013. PMID 13197385.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (October 1994). "Summary of notifiable diseases, United States, 1993" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 42 (53): i–xvii, 1–73. PMID 9247368. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (July 2009). "Summary of Notifiable Diseases --- United States, 2007" (PDF). MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 56 (53). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, eds. (2015). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ISBN 978-0990449119. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- ^ Bloch AB, Orenstein WA, Stetler HC, Wassilak SG, Amler RW, Bart KJ, et al. (October 1985). "Health impact of measles vaccination in the United States". Pediatrics. 76 (4): 524–532. doi:10.1542/peds.76.4.524. PMID 3931045. S2CID 6512947.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (March 2006). "Progress in reducing global measles deaths, 1999-2004" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 55 (9): 247–249. PMID 16528234. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ a b Parker AA, Staggs W, Dayan GH, Ortega-Sánchez IR, Rota PA, Lowe L, et al. (August 2006). "Implications of a 2005 measles outbreak in Indiana for sustained elimination of measles in the United States". The New England Journal of Medicine. 355 (5): 447–455. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa060775. PMID 16885548. S2CID 34529542.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (December 2006). "Measles--United States, 2005" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 55 (50): 1348–1351. PMID 17183226. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Hall V, Banerjee E, Kenyon C, Strain A, Griffith J, Como-Sabetti K, et al. (July 2017). "Measles Outbreak - Minnesota April-May 2017" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 66 (27): 713–717. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6627a1. PMC 5687591. PMID 28704350. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) Vaccine and Immunization Information". National Network for Immunization Information (NNii). 22 April 2010. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Jequier AM (2000). Male infertility: a guide for the clinician. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-632-05129-8. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2016.

- ^ a b Vesikari T, Sadzot-Delvaux C, Rentier B, Gershon A (July 2007). "Increasing coverage and efficiency of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine and introducing universal varicella vaccination in Europe: a role for the combined vaccine". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 26 (7): 632–638. doi:10.1097/INF.0b013e3180616c8f. PMID 17596807. S2CID 41981427.

- ^ "MMR vaccine questions and answers". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2004. Archived from the original on 25 July 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ^ Harnden A, Shakespeare J (July 2001). "10-minute consultation: MMR immunisation". BMJ. 323 (7303): 32. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7303.32. PMC 1120664. PMID 11440943.

- ^ Thompson GR, Ferreyra A, Brackett RG (1971). "Acute arthritis complicating rubella vaccination" (PDF). Arthritis and Rheumatism. 14 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1002/art.1780140104. hdl:2027.42/37715. PMID 5100638. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ a b Schattner A (June 2005). "Consequence or coincidence? The occurrence, pathogenesis and significance of autoimmune manifestations after viral vaccines". Vaccine. 23 (30): 3876–3886. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.03.005. PMID 15917108.

- ^ Carapetis JR, Curtis N, Royle J (October 2001). "MMR immunisation. True anaphylaxis to MMR vaccine is extremely rare". BMJ. 323 (7317): 869. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7317.869a. PMC 1121404. PMID 11683165.

- ^ Fox A, Lack G (October 2003). "Egg allergy and MMR vaccination". The British Journal of General Practice. 53 (495): 801–802. PMC 1314715. PMID 14601358. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013.

- ^ "Approval for label change". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 3 February 2015.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2012). Stratton K, Ford A, Rusch E, Clayton EW (eds.). Adverse Effects of Vaccines. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/13164. ISBN 978-0-309-21435-3. PMID 24624471. Bookshelf ID: NBK190024.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (1994). "Measles and mumps vaccines". In Stratton KR, Howe CJ, Johnston RB (eds.). Adverse Events Associated with Childhood Vaccines: Evidence Bearing on Causality. National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/2138. ISBN 978-0-309-07496-4. PMID 25144097. Bookshelf ID: NBK236291. Archived from the original on 24 August 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2007.

- ^ a b Colville A, Pugh S, Miller E (June 1994). "Withdrawal of a mumps vaccine". European Journal of Pediatrics. 153 (6): 467–468. doi:10.1007/BF01983415. PMID 8088305. S2CID 43300463.

- ^ Fullerton KE, Reef SE (October 2002). "Commentary: Ongoing debate over the safety of the different mumps vaccine strains impacts mumps disease control". International Journal of Epidemiology. 31 (5): 983–984. doi:10.1093/ije/31.5.983. PMID 12435772.

- ^ Sauvé LJ, Scheifele D (January 2009). "Do childhood vaccines cause thrombocytopenia?". Paediatrics & Child Health. 14 (1): 31–32. doi:10.1093/pch/14.1.31. PMC 2661332. PMID 19436461.

- ^ Black C, Kaye JA, Jick H (January 2003). "MMR vaccine and idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 55 (1): 107–111. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.01790.x. PMC 1884189. PMID 12534647.

- ^ Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, Linnell J, Casson DM, Malik M, et al. (February 1998). "Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children". Lancet. 351 (9103): 637–641. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11096-0. PMID 9500320. S2CID 439791. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 5 September 2007. (Retracted, see doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60175-4, PMID 20137807, Retraction Watch)

- ^ Jardine C (29 January 2010). "GMC brands Dr Andrew Wakefield 'dishonest, irresponsible and callous'". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2015.

- ^ The Editors of The Lancet (February 2010). "Retraction—Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children". Lancet. 375 (9713): 445. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60175-4. PMID 20137807. S2CID 26364726.

- ^ Triggle N (2 February 2010). "Lancet accepts MMR study 'false'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "General Medical Council, Fitness to Practise Panel Hearing, 24 May 2010, Andrew Wakefield, Determination of Serious Professional Misconduct" (PDF). General Medical Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ Meikle J, Sarah B (24 May 2010). "MMR row doctor Andrew Wakefield struck off register". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 24 May 2010.

- ^ Godlee F, Smith J, Marcovitch H (January 2011). "Wakefield's article linking MMR vaccine and autism was fraudulent". BMJ. 342 (jan05 1, c7452): c7452. doi:10.1136/bmj.c7452. PMID 21209060. S2CID 43640126.

- ^ a b National Health Service (2004). "MMR: myths and truths". Archived from the original on 13 September 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2007.

- ^ "Measles, Mumps, Rubella (MMR) Vaccine". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 24 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ "Autism and Vaccines - Vaccine Safety". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 24 August 2018. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2004). Immunization Safety Review. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/10997. ISBN 978-0-309-09237-1. PMID 20669467. Bookshelf ID: NBK25344.

- ^ "MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccine". UK National Health Service. 4 July 2022. Archived from the original on 28 November 2022. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- ^ MMR vs three separate vaccines:

- Halsey NA, Hyman SL, et al. (Conference Writing Panel) (May 2001). "Measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and autistic spectrum disorder: report from the New Challenges in Childhood Immunizations Conference convened in Oak Brook, Illinois, June 12-13, 2000". Pediatrics. 107 (5): E84. doi:10.1542/peds.107.5.e84. PMID 11331734.

- Leitch R, Halsey N, Hyman SL (January 2002). "MMR--Separate administration-has it been done?". Letter to the editor. Pediatrics. 109 (1): 172. doi:10.1542/peds.109.1.172. PMID 11773568.

- Miller E (January 2002). "MMR vaccine: review of benefits and risks". The Journal of Infection. 44 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1053/jinf.2001.0930. PMID 11972410.

- ^ "Doctors issue plea over MMR jab". BBC News. 26 June 2006. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Thomas J (2010). "Paranoia strikes deep: MMR vaccine and autism". Psychiatric Times. 27 (3): 1–6. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015.

- ^ Honda H, Shimizu Y, Rutter M (June 2005). "No effect of MMR withdrawal on the incidence of autism: a total population study". Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 46 (6): 572–579. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.579.1619. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01425.x. PMID 15877763. S2CID 10253998.

- ^ Wellington K, Goa KL (2003). "Measles, mumps, rubella vaccine (Priorix; GSK-MMR): a review of its use in the prevention of measles, mumps and rubella". Drugs. 63 (19): 2107–26. doi:10.2165/00003495-200363190-00012. PMID 12962524.

- ^ Plotkin SA, Vaheri A (May 1967). "Human fibroblasts infected with rubella virus produce a growth inhibitor". Science. 156 (3775): 659–661. Bibcode:1967Sci...156..659P. doi:10.1126/science.156.3775.659. PMID 6023662. S2CID 32622296.

- ^ Hayflick L, Moorhead PS (December 1961). "The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains". Experimental Cell Research. 25 (3): 585–621. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. PMID 13905658.

- ^ "Attenuvax Product Sheet" (PDF). Merck & Co. 2006. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2009. Retrieved 4 February 2009.

- ^ Merck Co. (2002). "MUMPSVAX (Mumps Virus Vaccine Live) Jeryl Lynn Strain" (PDF). Merck Co. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 August 2006. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

- ^ Young ML, Dickstein B, Weibel RE, Stokes J, Buynak EB, Hilleman MR (November 1967). "Experiences with Jeryl Lynn strain live attenuated mumps virus vaccine in a pediatric outpatient clinic". Pediatrics. 40 (5): 798–803. doi:10.1542/peds.40.5.798. PMID 6075651. S2CID 35878536.

- ^ "About the Vaccine – MMR and MMRV Vaccine Composition and Dosage". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 26 January 2021. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Reef SE, Plotkin SA (2018). "Rubella Vaccines". Plotkin's Vaccines. pp. 970–1000.e18. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-35761-6.00052-3. ISBN 9780323357616.

- ^ a b c Böröcz K, Csizmadia Z, Markovics Á, Farkas N, Najbauer J, Berki T, et al. (February 2020). "Application of a fast and cost-effective 'three-in-one' MMR ELISA as a tool for surveying anti-MMR humoral immunity: the Hungarian experience". Epidemiology and Infection. 148: e17. doi:10.1017/S0950268819002280. PMC 7019553. PMID 32014073.

- ^ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (March 2008). "Update: recommendations from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) regarding administration of combination MMRV vaccine" (PDF). MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 57 (10): 258–260. PMID 18340332. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ O'Leary ST, Suh CA, Marin M (November 2012). "Febrile seizures and measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine: what do primary care physicians think?". Vaccine. 30 (48): 6731–6733. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.08.075. PMID 22975026.

- ^ a b c "Vaccines and porcine gelatine" (PDF). Public Health England. August 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

- ^ Pager T (9 April 2019). "'Monkey, Rat and Pig DNA': How Misinformation Is Driving the Measles Outbreak Among Ultra-Orthodox Jews". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 14 April 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- World Health Organization (January 2009). The immunological basis for immunization series: module 7: measles (update 2009). World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/44038. ISBN 9789241597555.

- World Health Organization (November 2010). The immunological basis for immunization series: module 16: mumps. World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/97885. ISBN 9789241500661.

- World Health Organization (December 2008). The immunological basis for immunization series: module 11: rubella. World Health Organization (WHO). hdl:10665/43922. ISBN 9789241596848.

- Ramsay M, ed. (April 2013). Immunisation against infectious disease. Public Health England.

- "Measles: the green book, chapter 21". 31 December 2019.

- "Mumps: the green book, chapter 23". 4 April 2013.

- "Rubella: the green book, chapter 28". 4 April 2013.

- Hamborsky J, Kroger A, Wolfe S, eds. (2015). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (13th ed.). Washington D.C.: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). ISBN 978-0990449119.

- "Chapter 13: Measles". 10 July 2024.

- "Chapter 15: Mumps". 29 July 2024.

- "Chapter 20: Rubella". 29 July 2024.

- Roush SW, Baldy LM, Hall MA, eds. (March 2019). Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases. Atlanta GA: U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- "Chapter 7: Measles". May 2024.

- "Chapter 9: Mumps". 19 December 2023.

- "Chapter 14: Rubella". 22 August 2023.

External links

[edit]- Measles-Mumps-Rubella Vaccine at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)