M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System

| M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (MLRS) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Multiple rocket launcher |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1983–present |

| Used by | See Operators |

| Wars | |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Ling-Temco-Vought[1] |

| Designed | 1977 |

| Manufacturer | |

| Unit cost | Domestic cost: $2.3 million per one launcher (FY 1990) $4.7 million (in 2023)[2] per one launcher $168,000 per one M31 GMLRS (FY 2023)[3] Export cost: $434,000 per one M31ER GMLRS (FY 2022)[4] |

| Produced | 1980–Present[5] |

| Variants | M270, M270A1, M270A2, MARS II, LRU, MLRS-I |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 52,990 lb (24,040 kg) (combat loaded w/ 12 rockets)[6] |

| Length | 274.5 in (6.97 m)[6] |

| Width | 117 in (3.0 m)[6] |

| Height | 102 in (2.59 m) (launcher stowed)[6] |

| Crew | 3 |

| Caliber | 227 mm (8.9 in) |

| Effective firing range |

|

| Maximum firing range |

|

| Armor | 5083 aluminum hull, 7039 aluminum cab[6] |

Main armament | or 4 x PrSM |

| Engine | Cummins VTA-903 diesel engine[6] 500 hp (373 kW) at 2600 rpm[6] 600 hp (447 kW) (M270A1)[1] |

| Power/weight | 18.9 hp/ST (15.5 kW/t) (M270)[6] |

| Suspension | Torsion bar[6] |

Operational range | 300 mi (483 km)[6] |

| Maximum speed | 40 mph (64.4 km/h)[6] |

The M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System (M270 MLRS) is an American armored self-propelled multiple launch rocket system.

The U.S. Army variant of the M270 is based on the chassis of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle. The first M270s were delivered in 1983, and were adopted by several NATO and non-NATO militaries. The platform first saw service with the United States in the 1991 Gulf War. It has received multiple improvements since its inception, including the ability to fire guided missiles. M270s provided by the United Kingdom have seen use in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[8]

Description

[edit]Background

[edit]In the early 1970s, the Soviet Union had a clear advantage over U.S. and NATO forces in terms of rocket artillery. Soviet doctrine dictated large-scale bombardment of a target area with large numbers of truck-mounted multiple rocket launchers (MRLs), such as the BM-21 "Grad".[9] By contrast, U.S. artillerists favored conventional large-caliber artillery for its relative accuracy and logistical efficiency. As a result, U.S. rocket artillery was limited to the remaining stock of World War II-era systems.[10]

This mindset began to change following the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which saw heavy casualties, especially from rear-area weapons like surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). Israel effectively employed rocket artillery against these targets. The United States predicted that this requirement would persist in the event of a war in Europe. Thus, the need had arisen for a system that could engage enemy air defenses and provide counter-battery fire, freeing large-caliber artillery units to provide call-for-fire artillery support for ground forces.[10]

The MLRS was initially conceived as the General Support Rocket System (GSRS). In December 1975, the U.S. Army Missile Command issued a request for proposal to industry to assist in determining the best technical approach for the GSRS.[11] In March 1976, the Army awarded contracts to Boeing, Emerson Electric, Martin Marietta, Northrop and Vought to explore the concept definition of the GSRS.[1] In September 1977, Boeing Aerospace and Vought were awarded contracts to develop prototypes of the GSRS.[1]

In 1978, the U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Command made changes to the program so that the GSRS could be manufactured in Europe.[1] This was to allow European nations, who had been independently pursuing their own MLRS programs, to buy in to the program.[10] In July 1979, the United States, West Germany, France and the United Kingdom signed a memorandum of understanding for joint development and production of GSRS. In November 1979, GSRS was accordingly redesignated the multiple launch rocket system.[11] Both competitors delivered three MLRS prototypes to the Army.[1]

The Army evaluated the MLRS prototypes from December 1979 – February 1980. In May 1980, the Army selected the Vought system. In early 1982, Vought began low-rate initial production.[12] In August 1982, the first production models were delivered.[10] In early 1983, the first units were delivered to the 1st Infantry Division.[12] In March 1983, the first operational M270 battery was formed. In September 1983, the first unit was sent to West Germany.[10]

European nations produced 287 MLRS systems, with the first being delivered in 1989.[12] Some 1,300 M270 systems have been manufactured in the United States and in Western Europe to date, along with more than 700,000 rockets of all kinds, including over 70,000 GMLRS guided munitions as of March 2024.[13][14]

Overview

[edit]The M270 MLRS weapons system is collectively known as the M270 MLRS Self-Propelled Loader/Launcher (SPLL). The SPLL is composed of two primary subsystems; the M269 Launcher-Loader Module (LLM) houses the electronic fire-control system and sits atop the M993 Carrier Vehicle.[15]

The M993 is the designation of the M987 carrier when it is used in the MLRS. The M987/M993 is a lengthened derivative of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle chassis,[12] in which the ground contact length is increased from 154 inches (390 cm) to 170.5 inches (433 cm).[16] Originally called the Fighting Vehicle System, the M987 chassis was designed to serve as the basis for many other vehicles. These included the XM1070 Electronic Fighting Vehicle, the M4 Command and Control Vehicle, the Armored Treatment and Transport Vehicle and the Forward Area Armored Logistics System, the latter encompassing three vehicles, including the XM1007 AFARV rearm vehicle.[12][17]

The original GSRS plan called for 210 mm diameter rockets. After European allies became involved with the project, these were replaced with 227 mm rockets in order to accommodate the AT2 mine.[12]

Cold War doctrine for the M270 called for the vehicles to spread out individually and hide until needed, then move to a firing position and launch their rockets, immediately move away to a reloading point, then move to a completely new hiding position near a different firing point. These shoot-and-scoot tactics were planned to avoid susceptibility to Soviet counter-battery fire. One M270 firing 12 M26 rockets would drop 7,728 bomblets, and one MLRS battery of nine launchers firing 108 rockets had the equivalent firepower of 33 battalions of cannon artillery.[10]

The system can fire rockets or MGM-140 ATACMS missiles, which are contained in interchangeable pods. Each pod contains six standard rockets or one guided ATACMS missile; the two types cannot be mixed. The LLM can hold two pods at a time, which are handloaded using an integrated winch system. All twelve rockets or two ATACMS missiles can be fired in under a minute. One launcher firing twelve rockets can completely blanket one square kilometre with cluster munitions; a typical MLRS cluster salvo would involve three M270 vehicles firing together. With each rocket containing 644 M77 submunitions, the entire salvo would drop 23,184 submunitions in the target area. However, at a two percent dud rate, that would leave approximately 400 undetonated bombs scattered over the area, which could endanger friendly troops and civilians.[18]

Production of the M270 ended in 2003, when a last batch was delivered to the Egyptian Army.[citation needed] In 2003, the U.S. Army began low-rate production of the M142 HIMARS. The HIMARS fires all of the munitions of the MLRS, and is based on the chassis of the Family of Medium Tactical Vehicles.[19] As of 2012, BAE Systems still had the capability to restart production of the MLRS.[1]

In 2006, MLRS was upgraded to fire guided rounds. Phase I testing of a guided unitary round (XM31) was completed on an accelerated schedule in March 2006. Due to an Urgent Need Statement, the guided unitary round was quickly fielded and used in action in Iraq.[20] Lockheed Martin also received a contract to convert existing M30 Dual-Purpose Improved Conventional Munition (DPICM) GMLRS rockets to the XM31 unitary variant.[21]

The M31 GMLRS Unitary rocket transformed the M270 into a point target artillery system for the first time. Due to Global Positioning System (GPS) guidance and a single 200 lb (91 kg) high-explosive warhead, the M31 could hit targets accurately with less chance of collateral damage while needing fewer rockets to be fired, reducing logistical requirements. The unitary warhead also made the MLRS able to be used in urban environments. The M31 had a dual-mode fuse with point detonation and delay options to defeat soft targets and lightly fortified bunkers respectively, with the upgraded M31A1 equipped with a multi-mode fuse adding a proximity airburst mode for use against personnel in the open; proximity mode can be set for 3 or 10 meters (9.8 or 32.8 ft) Height of Burst (HOB). The GMLRS has a minimum engagement range of 15 km (9.3 mi) and can hit a target out to 70 km (43 mi), impacting at a speed of Mach 2.5.[22][23] In 2009 Lockheed Martin announced that a GMLRS had been successfully test fired out to 92 km (57 mi).[24]

In April 2011, the first modernized MLRS II and M31 GMLRS rocket were handed over to the German Army's Artillery School in Idar Oberstein. The German Army operates the M31 rocket up to a range of 90 kilometres (56 mi).[25] A German developmental artillery system, called the Artillery Gun Module, has used the MLRS chassis on its developmental vehicles.[26]

In 2012, a contract was issued to improve the armor of the M270s and improve the fire control to the standards of the M142 HIMARS.[27] In June 2015, the M270A1 conducted tests of firing rockets after upgrades from the Improved Armored Cab project, which provides the vehicle with an enhanced armored cab and windows.[28]

In early March 2021, Lockheed announced they had successfully fired an extended-range version of the GMLRS out to 80 km (50 mi), part of an effort to increase the rocket's range to 150 km (93 mi).[29] Later in March the ER GMLRS was fired out to 135 km (84 mi).[30] In September 2023, Lockheed announced an ER GMLRS test achieved its maximum range of 150 km (93 mi).[31] The U.S. Army approved the ER GMLRS for production in May 2024.[32]

Service history

[edit]

When first deployed with the U.S. Army, the MLRS was used in a composite battalion consisting of two batteries of traditional artillery (howitzers) and one battery of MLRS SPLLs (self-propelled loader/launchers). The first operational Battery was C Battery, 3rd Battalion, 6th Field Artillery, 1st Infantry Division (Ft. Riley, Kansas) in 1982. The first operational organic or "all MLRS" unit was 6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery.[33]

Originally, a battery consisted of three platoons with three launchers each for nine launchers per battery; by 1987, 25 MLRS batteries were in service. In the 1990s, a battery was reduced to six launchers.[10]

The 6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery was reactivated as the Army's first MLRS battalion in October 1984, and became known as the "Rocket Busters". In March 1990, the unit deployed to White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico to conduct the Initial Operational Test and Evaluation of the Army Tactical Missile System. The success of the test provided the Army with a highly accurate, long range fire support asset.[citation needed]

Gulf War

[edit]The first combat use of the MLRS occurred in the Gulf War.[17] The U.S. deployed over 230 MLRS during Operation Desert Storm, and the UK an additional 16.[12]

In September 1990, the 6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery deployed to Saudi Arabia in support of Operation Desert Shield. Assigned to the XVIII Airborne Corps Artillery, the unit played a critical role in the early defense of Saudi Arabia. As Desert Shield turned into Desert Storm, the Battalion was the first U.S. Field Artillery unit to fire into Iraq. Over the course of the war, the 6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery provided timely and accurate rocket and missile fires for both U.S. corps in the theater, the 82nd Airborne Division, the 6th French Light Armored Division, the 1st Armored, 1st Infantry Division, the 101st Airborne Division, and the 24th Infantry Division (Mechanized).

A Battery 92nd Field Artillery (MLRS) was deployed to the Gulf War in 1990 from Ft. Hood Texas. 3/27th FA (MLRS) out of Fort Bragg deployed in support of Operation Desert Shield in August 1990. A/21st Field Artillery (MLRS) – 1st Cavalry Division Artillery deployed in support of Operation Desert Shield in September 1990. In December 1990, A-40th Field Artillery (MLRS) – 3rd Armored Division Artillery (Hanau), 1/27th FA (MLRS) part of the 41st Field Artillery Brigade (Babenhausen) and 4/27th FA (MLRS) (Wertheim) deployed in support of Operation Desert Shield from their bases in Germany and 1/158th Field Artillery from the Oklahoma Army National Guard deployed in January 1991.

MLRS launchers were deployed during Operation Desert Storm. Its first use was on 18 January 1991, when Battery A of the 6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery fired eight ATACMS missiles at Iraqi SAM sites. In one engagement, three MLRS batteries fired 287 rockets at 24 separate targets in less than five minutes, an amount that would have taken a cannon battalion over an hour to fire.[10] In early February 1991, 4-27 FA launched the biggest MLRS night fire mission in history,[34] firing 312 rockets in a single mission.[citation needed] When ground operations began on 24 February 1991, 414 rockets were fired as the U.S. VII Corps advanced. Out of the 57,000 artillery rounds fired by the end of the war, 6,000 were MLRS rockets plus 32 ATACMS.[10]

Middle East

[edit]The MLRS has since been used in numerous military engagements, including the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In March 2007, the British Ministry of Defence decided to send a troop of MLRS to support ongoing operations in Afghanistan's southern province of Helmand, using newly developed guided munitions.

In September 2005, the GMLRS was first used in Iraq, when two rockets were fired in Tal Afar over 50 kilometres (31 mi) and hit insurgent strongholds, killing 48 Iraqi fighters.[10]

During the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, Israel used the M270 for the first time since 2006, to fire on Hamas targets in the Gaza Strip.[35]

Ukraine

[edit]During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United States considered sending the MLRS as part of military aid to Ukraine. Concerns were raised that this system could be used to hit targets inside Russia.[36] US President Joe Biden initially declined to send it to Ukraine,[37] but on May 31 he announced that the M142 HIMARS, another vehicle capable of firing GMLRS rockets, would be supplied.[38]

On 7 June 2022, British defence secretary Ben Wallace announced that the UK would send three (later increased to six) MLRS to aid Ukrainian forces.[39][40] On 15 June, Germany announced it would send three of its MARS vehicles from German Army stocks.[41] Ukraine announced they had received the first M270s on 15 July.[42] The German defence secretary Christine Lambrecht announced the arrival of the vehicles they contributed on 26 July 2022,[43] and on 15 September Lambrecht announced that Germany would transfer two more.[44][45]

During the Russo-Ukrainian War, Russian forces have relied on electronic warfare to jam GPS signals. The inertial navigation system is immune to jamming, but less accurate than when paired with GPS coordinates and can miss the target.[46]

Variants

[edit]

- M270 is the original version, which carries a weapon load of 12 rockets in two six-pack pods. This armored, tracked mobile launcher uses a stretched Bradley chassis and has a high cross-country capability.[citation needed]

- M270A1 was the result of a 2005 upgrade program for the U.S. Army, and later on for several other states. The launcher appears identical to M270, but incorporates the Improved Fire Control System (IFCS) and an improved launcher mechanical system (ILMS). This allows for significantly faster launch procedures and the firing of GMLRS rockets with GPS-aided guidance. The US Army updated 225 M270 to this standard. When Bahrain ordered an upgrade of nine to "A1 minimum configuration" in 2022, it was stated to include CFCS.[47]

- M270B1 British Army variant of the M270A1, which includes an enhanced armor package to give the crew better protection against IED attacks. Following an agreement struck with the United States Department of Defense, the British Army will be embarking on a five-year programme to update the M270B1 to the M270A2 standard. They are developing some UK-specific systems, including Composite Rubber Tracks (CRT), and a vehicle camera and radar system. Upgrade of the first tranche of launchers started in March 2022, with the fleet going through production over a four-year period. A new Fire Control System will be developed collaboratively with the US, the UK, Italy, and Finland.[48]

- M270C1 was an upgrade proposal from Lockheed Martin involving the M142's Universal Fire Control System (UFCS) instead of IFCS.

- M270D1 Finnish Army variant of the M270A1 that uses the M142's Universal Fire Control System (UFCS).[49]

- MARS II / LRU / MLRS-I is a European variant of the M270A1 involving Germany, France, and Italy. Mittleres Artillerieraketensystem (MARS II)[50][51] The launchers are equipped with the European Fire Control System (EFCS) designed by Airbus Defence and Space.[52] The EFCS disables the firing of submunitions-carrying rockets to ensure full compliance with the Convention on Cluster Munitions.

- M270A2 is a 2019 upgrade program to the US Army variant, which includes the new Common Fire Control System (CFCS) to allow the use of the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM). The update also includes a new 600 hp engine, upgraded and rebuilt transmission, and improved cabin armor protection. The U.S. Army will eventually upgrade its entire fleet of 225 M270A1 and an additional 160 decommissioned M270A0 launchers.[53]

Rockets and missiles

[edit]

The M270 system can fire MLRS Family of Munitions (MFOM) rockets and artillery missiles, which are manufactured and used by a number of platforms and countries. These include:

MLRS

[edit]M26 and M28 rocket production began in 1980. Until 2005 they were the only rockets available for the M270 system. When production of the M26 series ceased in 2001, a total of 506,718 rockets had been produced.[54] Each rocket pod contains 6 identical rockets. The M26 rocket and its derivatives were removed from the US Army's active inventory in June 2009, as they did not satisfy a July 2008 Department of Defense policy directive, issued under President George W. Bush, that US cluster munitions that leave more than 1% of submunitions as unexploded ordnance must be destroyed by the end of 2018.[55] (The United States is not a party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions, which prohibits them). The last use of the M26 rocket prior to its use with the GLSDB occurred during Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003.[55]

- M26 rockets carrying 644 DPICM M77 submunitions. Range: 15–32 kilometres (9.3–19.9 mi).[54] The submunitions that were used in these rockets prior to their use with the GLSDB covered an area of 0.23 km2. Dubbed "Steel Rain" by Iraqi soldiers, M26 rockets were used extensively during Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom. Initially fielded in 1983, the rockets have a shelf life of 25 years.[56] The US started destroying its M26 stocks in 2007, when the US Army requested $109 million for the destruction of 98,904 M26 MLRS rockets from fiscal year 2007 to fiscal year 2012.[55] M26 rockets were removed from the US Army's active inventory in June 2009 and the remaining rockets were being destroyed as of 2009,[57] but the US requirement to destroy them was removed in 2017.[55] The UK and the Netherlands destroyed their stock of 60,000 M26 rockets by 2013, Italy destroyed its 3,894 rockets by 31 October 2015,[58] Germany its 26,000 by 25 November 2015,[59][60] and France its 22,000 by 2017.[61]

- M26A1 ER rockets carrying 518 M85 submunitions. Range: 15–45 kilometres (9.3–28.0 mi).[54] The M85 submunitions are identical to the M77 submunitions, except for the fuze. The M85 use the M235 mechanical/electronic self-destruct fuze to reduce hazardous duds and the potential for fratricide or collateral damage.[62]

- M26A2 ER rockets carrying 518 M77 submunitions. Interim solution until the M26A1 ER entered service. Range: 15–45 kilometres (9.3–28.0 mi).[54] The M26A2 ER rockets have been retired from US Army service and the remaining rockets are being[when?] destroyed.[57]

- M28 practice rockets. A M26 variant with three ballast containers and three smoke marking containers in place of the submunition payload. Production ceased in favor of the M28A1.

- M28A1 Reduced Range Practice Rocket (RRPR) with blunt nose. Range reduced to 9 kilometres (5.6 mi). Production ceased in favor of the M28A2.

- M28A2 Low Cost Reduced Range Practice Rocket (LCRRPR) with blunt nose. Range reduced to 9 kilometres (5.6 mi).

- AT2 German M26 variant carrying 28 AT2 anti-tank mines. Range: 15–38 kilometres (9.3–23.6 mi)

GMLRS

[edit]Guided multiple launch rocket system (GMLRS) rockets have a GPS-aided inertial navigation system and extended range. Flight control is accomplished by four forward-mounted canards driven by electromechanical actuators. GMLRS rockets were introduced in 2005 and can be fired from the M270A1 and M270A2, the European M270A1 variants (British Army M270B1, German Army MARS II, French Army Lance Roquette Unitaire (LRU), Italian Army MLRS Improved (MLRS-I), Finnish Army M270D1), and the lighter M142 HIMARS launchers.

M30 rockets have an area-effects warhead, while M31 rockets have a unitary warhead, but the rockets are otherwise identical.[63] By December 2021, 50,000 GMLRS rockets had been produced,[64] with yearly production then exceeding 9,000 rockets. Each rocket pod contains 6 identical rockets. The cost of an M31 missile is estimated at $500,000,[65] though this may be the "export price", always higher than the amount charged to the U.S. Army.[66] According to the U.S. Army's budget, it will pay about $168,000 for each GMLRS in 2023.[67][68][69]

Both Lockheed Martin and the U.S. Army report that the GMLRS has a maximum range of 70+ km (43+ mi).[70][71] According to a U.S. Department of Defense document the maximum demonstrated performance of a GMLRS is 84 km (52 mi),[72] a figure also reported elsewhere.[54][63] Another source reports a maximum range of about 90 km (56 mi).[73] In 2009 Lockheed Martin announced that a GMLRS had been successfully test fired 92 km (57 mi).[74]

During the Russo-Ukrainian War, Russian forces have relied on electronic warfare to jam GPS signals. The inertial navigation system is immune to jamming, but less accurate than when paired with GPS coordinates and can miss the target. Ukraine attempted to mitigate the jamming by changes to the software and attacking Russian jamming systems by artillery.[46]

- M30 rockets carrying 404 DPICM M101 submunitions. Range: 15–92 kilometres (9.3–57.2 mi). 3,936 produced between 2004 and 2009. Production ceased in favor of the M30A1.[63] The remaining US Army M30 rockets have been converted to the M31 (unitary warhead) variant.[21]

- M30A1 rockets with Alternative Warhead (AW). Range: 15–92 kilometres (9.3–57.2 mi). The M30's submunitions are replaced with about 182,000 pre-formed tungsten fragments, to give area effects, but without leaving unexploded submunitions.[75] The system uses a proximity sensor fuze mode with a 10 meter height of burst.[76] Entered production in 2015.[63][54]

- M30A2 rockets with Alternative Warhead (AW). Range: 15–92 kilometres (9.3–57.2 mi). Improved M30A1 with Insensitive Munition Propulsion System (IMPS). The only M30 variant in production since 2019.[77]

- M31 rockets with 200-pound (91 kg) high-explosive unitary warhead. Range: 15–92 kilometres (9.3–57.2 mi). Entered production in 2005. The warhead is produced by General Dynamics and contains 23 kg (51 lb) of PBX-109 high explosive in a steel blast-fragmentation case.[78][79]

- M31A1 rockets with 200-pound (91 kg) high-explosive unitary warhead. Range: 15–92 kilometres (9.3–57.2 mi). Improved M31 with new multi-mode fuze that added airburst to the M31's fuze point detonation and delay.[80]

- M31A2 rockets with 200-pound (91 kg) high-explosive unitary warhead. Range: 15–92 kilometres (9.3–57.2 mi). Improved M31A1 with Insensitive Munition Propulsion System (IMPS). The only M31 variant in production since 2019.[77]

- M32 SMArt German variant produced by Diehl Defence carrying 4 SMArt anti-tank submunitions and new flight software. Developed for MARS II, but has not been ordered as of 2019, so is not in service.[81]

- ER GMLRS rockets with extended range of up to 150 km (93 mi).[82] Uses a slightly bigger rocket motor, a newly designed hull, and tail-driven guidance, while still being six per pod. It will come in unitary and AW variants.[83] The first successful test flight was in March 2021.[84] In early 2021, Lockheed Martin anticipated putting it into its production line in the fiscal year 2023 contract award and was planning to produce the new rockets at its Camden facility.[30] In 2022 Finland became the first foreign customer to order it.[85]

GLSDB

[edit]The Ground Launched Small Diameter Bomb is a weapon made by Boeing and the Saab Group, who modified Boeing's GBU-39 Small Diameter Bomb (SDB) with the addition of a rocket motor. It has a range of up to 150 km (93 mi).

ATACMS

[edit]The Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) is a series of 610 mm surface-to-surface missile (SSM) with a range of up to 300 kilometres (190 mi). Each rocket pod contains one ATACMS missile. As of 2022 only the M48, M57, and M57E1 remain in the US military's active inventory.

- M39 (ATACMS BLOCK I) missile with inertial guidance. The missile carries 950 M74 Anti-personnel and Anti‑materiel (APAM) bomblets. Range: 25–165 kilometres (16–103 mi). 1,650 M39 were produced between 1990 and 1997, when production ceased in favor of the M39A1. During Desert Storm 32 M39 were fired at Iraqi targets and during Operation Iraqi Freedom a further 379 M39 were fired.[63][54] The remaining M39 missiles are being updated since 2017 to M57E1 missiles.[86][87] The M39 is the only ATACMS variant which can be fired by all M270 and M142 variants.[88]

- M39A1 (ATACMS BLOCK IA) missile with GPS-aided guidance. The missile carries 300 M74 Anti-personnel and Anti‑materiel (APAM) bomblets. Range: 20–300 kilometres (12–186 mi). 610 M39A1 were produced between 1997 and 2003. During Operation Iraqi Freedom 74 M39A1 were fired at Iraqi targets.[63][54] The remaining M39A1 missiles are being updated since 2017 to M57E1 missiles.[86][87] The M39A1 and all subsequently introduced ATACMS missiles can only be used with the M270A1 (or variants thereof) and the M142.[89]

- M48 (ATACMS Quick Reaction Unitary (QRU) missile with GPS-aided guidance. It carries the 500-pound (230 kg) WDU-18/B penetrating high explosive blast fragmentation warhead of the US Navy's Harpoon anti-ship missile, which was packaged into the newly designed WAU-23/B warhead section. Range: 70–300 kilometres (43–186 mi). 176 M48 were produced between 2001 and 2004, when production ceased in favor of the M57. During Operation Iraqi Freedom 16 M48 were fired at Iraqi targets a further 42 M48 were fired during Operation Enduring Freedom.[63][54] The remaining M48 missiles remain in the US Army and US Marine Corps' arsenal.

- M57 (ATACMS TACMS 2000) missile with GPS-aided guidance. The missile carries the same WAU-23/B warhead section as the M48. Range: 70–300 kilometres (43–186 mi). 513 M57 were produced between 2004 and 2013.[63][54]

- M57E1 (ATACMS Modification (MOD) missile with GPS-aided guidance. The M57E1 is the designation for upgraded M39 and M39A1 with re-grained motor, updated navigation and guidance software and hardware, and a WAU-23/B warhead section instead of the M74 APAM bomblets. The M57E1 ATACMS MOD also includes a proximity sensor for airburst detonation.[86] Production commenced in 2017 with an initial order for 220 upgraded M57E1.[63][54] The program is slated to end in 2024 with the introduction of the Precision Strike Missile (PrSM), which will replace the ATACMS missiles in the US arsenal.

PrSM

[edit]The Precision Strike Missile (PrSM) is a new series of GPS-guided missiles, which will begin to replace ATACMS missiles from 2024. PrSM carries a newly designed area-effects warhead and has a range of 60–499 kilometres (37–310 mi). PrSM missiles can be launched from the M270A2 and the M142, with rockets pods containing 2 missiles. As of 2022 the PrSM is in low rate initial production with 110 missiles being delivered to the US military over the year. PrSM will enter operational service in 2023.[90][63][91]

Reverse engineering

[edit]In the Turkish SAGE-227 project A/B/C/D medium-range composite-fuel artillery rocket and SAGE-227 F experimental guided rocket were developed from reverse engineering HIMARS missiles due to trust issues[clarification needed] in 2019.

Turkey PARS SAGE-227 F (Turkey): Experimental Guided MLRS (GMLRS) developed by TUBITAK-SAGE to replace the M26 rockets.

Turkey PARS SAGE-227 F (Turkey): Experimental Guided MLRS (GMLRS) developed by TUBITAK-SAGE to replace the M26 rockets.

Israeli rockets

[edit]Israel developed its own rockets to be used in the "Menatetz", an upgraded version of the M270 MLRS.

- Trajectory Corrected Rocket (TCS/RAMAM): In-flight trajectory corrected for enhanced accuracy.

- Ra'am Eithan ("Strong Thunder"): an improved version of the TCS/RAMAM (in-flight trajectory corrected for enhanced accuracy) with significantly decreased percentage of duds.

British missiles

[edit]As part of the circa £2bn Land Deep Fires Programme (LDFP), the British Army intends a large scale modernization effort of its GMLRS capability involving both a increase in the number of launchers and an expansion in the variety of effectors available.[92] The British Army launchers will be upgraded to the M270A2 standard and additional launchers will be purchased and upgraded from stockpiles likely from the US for a total of 76 launchers and 9 recovery vehicles.[92][93] M270A2 will include a number of British-specific upgrades such as new composite rubber tracks, radar and video sensors, as well as the new jointly developed fire control system from the UK, US, Italy, and Finland.[93]

Alongside the procurement of GMLRS-ER and the possible procurement of the PrSM, the UK is also developing two additional effectors under its 'one launcher, many payloads' concept:

- Dispensing-Rocket Payload: developed under 'Technical Demonstrator Program 5', a UK designed dispensing payload that replaces the standard warheads for the GMLRS-ER and PrSM. It is capable of deploying small UAVs such as Lockheed Martin UK's OUTRIDER for ISTAR, battle damage assessment, and electronic warfare; or a number of Thales UK's free-fall lightweight multirole missile (FFLMM) for anti-armour capability.[94][95]

- Land Precision Strike (LPS): derived from MBDA UK's CAMM and Brimstone products; designed to complement the GMLRS-ER by enabling the engagement of high value, time sensitive, and mobile targets out to 80–150 km (47.7-93.2 mi).[96][95][93][97] MBDA graphics show that LPS could be used on a number of platforms including the M270 with an additional vehicle sporting the two way data link pod, Boxer (as a mission module), or MBDA's iLauncher.[96]

French missiles

[edit]Developed by MBDA France and Safran as a candidate for the Feux Longue Portée-Terre (FLP-T) or Land Long Range Fires procurement program, the Thundart guided artillery rocket is designed to have a range of 150 km and the ability to be fired from the French version of the M270, the Lance-Roquettes Unitaire (LRU).[98]

Alternative Warhead Program

[edit]In April 2012, Lockheed Martin received a $79.4 million contract to develop a GMLRS incorporating an Alliant Techsystems-designed alternative warhead to replace DPICM cluster warheads. The AW version is designed as a drop-in replacement with little modification needed to existing rockets. An Engineering and Manufacturing Development (EMD) program was to last 36 months, with the alternative warhead GMLRS expected to enter service in late 2016.[99] The AW warhead is a large airburst fragmentation warhead that explodes 30 ft (9.1 m) over a target area to disperse penetrating projectiles. Considerable damage is caused to a large area while leaving behind only solid metal penetrators and inert rocket fragments[100] from a 90 kilograms (200 lb) warhead containing approximately 182,000 preformed tungsten fragments.[101] The unitary GMLRS also has an airburst option, but while it produces a large blast and pieces of shrapnel, the AW round's small pellets cover a larger area.[102]

In May 2013, Lockheed and ATK test fired a GMLRS rocket with a new cluster munition warhead developed under the Alternative Warhead Program (AWP), aimed at producing a drop-in replacement for DPICM bomblets in M30 guided rockets. It was fired by an M142 HIMARS and traveled 35 km (22 mi) before detonating. The AWP warhead will have equal or greater effect against materiel and personnel targets, while leaving no unexploded ordnance behind.[103]

In October 2013, Lockheed conducted the third and final engineering development test flight of the GMLRS alternative warhead. Three rockets were fired from 17 kilometers (11 mi) away and destroyed their ground targets. The Alternative Warhead Program then moved to production qualification testing.[104] The fifth and final Production Qualification Test (PQT) for the AW GMLRS was conducted in April 2014, firing four rockets from a HIMARS at targets 65 kilometers (40 mi) away.[105]

In July 2014, Lockheed successfully completed all Developmental Test/Operational Test (DT/OT) flight tests for the AW GMLRS. They were the first tests conducted with soldiers operating the fire control system, firing rockets at mid and long-range from a HIMARS. The Initial Operational Test and Evaluation (IOT&E) exercise was to be conducted in fall 2014.[106]

In September 2015, Lockheed received a contract for Lot 10 production of the GMLRS unitary rocket, which includes the first order for AW production.[107]

Specifications

[edit]

- Entered service: 1982, US Army

- First use in action: 1991, Gulf War

- Crew: 3

- Weight loaded: 24,756 kilograms (54,578 lb)

- Length: 6.86 meters (22 ft 6 in)

- Width: 2.97 meters (9 ft 9 in)[108]

- Height (stowed): 2.57 m (8 ft 5 in)[109]

- Height (max. elevation): not available

- Maximum road speed: 64 km/h (40 mph)

- Cruise range: 480 kilometres (300 mi)

- Reload time: 4 min (M270) 3 min (M270A1)

- Engine: Turbocharged V8 Cummins VTA903 diesel 500 hp ver2.

- Transmission: Cross-drive turbo transmission, fully electronically controlled

- Average unit cost: $2.3 million per launcher (FY 1990),[citation needed] $168,000 per M31 GMLRS rocket (FY 2023)[110]

Operators

[edit]

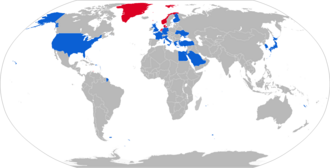

Current operators

[edit]M270

[edit] Egypt: Egyptian Army (42)[111]

Egypt: Egyptian Army (42)[111] Greece: Hellenic Army (36) ATACMS operational.[111]

Greece: Hellenic Army (36) ATACMS operational.[111] Japan: Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (99).[111]

Japan: Japan Ground Self-Defense Force (99).[111] Saudi Arabia: Saudi Arabian Army (180)[citation needed]

Saudi Arabia: Saudi Arabian Army (180)[citation needed] Turkey: Turkish Army (12) ATACMS BLK 1A operational.[111]

Turkey: Turkish Army (12) ATACMS BLK 1A operational.[111]

M270A1

[edit] Bahrain: Royal Bahraini Army (9) ATACMS operational.[111]

Bahrain: Royal Bahraini Army (9) ATACMS operational.[111] Finland: Finnish Army (41) M270D1 launchers which will be upgraded to M270A2 variants.[112]

Finland: Finnish Army (41) M270D1 launchers which will be upgraded to M270A2 variants.[112] France: French Army (13),[113] European M270A1 variant called lance-roquettes unitaire (LRU).[113][52]

France: French Army (13),[113] European M270A1 variant called lance-roquettes unitaire (LRU).[113][52] Germany: German Army (114 M270 stored, 40 MARS II), European M270A1 variant called Mittleres Artillerieraketensystem (MARS II)[50][51][52] It is set to be replaced by the GMARS.[114]

Germany: German Army (114 M270 stored, 40 MARS II), European M270A1 variant called Mittleres Artillerieraketensystem (MARS II)[50][51][52] It is set to be replaced by the GMARS.[114] Israel: Israeli Ground Forces (64), called "Menatetz" מנתץ, "Smasher".[115]

Israel: Israeli Ground Forces (64), called "Menatetz" מנתץ, "Smasher".[115] Italy: Italian Army (22), European M270A1 variant called MLRS Improved (MLRS-I).[50]

Italy: Italian Army (22), European M270A1 variant called MLRS Improved (MLRS-I).[50] South Korea: Republic of Korea Army (58) 48 M270s and 10 M270A1s. ATACMS operational.[111][116][117]

South Korea: Republic of Korea Army (58) 48 M270s and 10 M270A1s. ATACMS operational.[111][116][117] United Kingdom: British Army (44), M270A1 variant called M270B1, which includes an enhanced armor package.[118] The UK will increase its operational fleet to 85 by 2030, as well as having more vehicles in reserve.[119] 9 of the UK's M270s will be upgraded to the M270A2 variant through a $32 million programme.[120]

United Kingdom: British Army (44), M270A1 variant called M270B1, which includes an enhanced armor package.[118] The UK will increase its operational fleet to 85 by 2030, as well as having more vehicles in reserve.[119] 9 of the UK's M270s will be upgraded to the M270A2 variant through a $32 million programme.[120] Ukraine: Ukrainian Army (16) The United Kingdom, Norway, France,[121] Germany and Italy[122] provided more than ten systems to Ukraine in 2022.[36][123][124][125] In October 2023, the US donated ATACMS for use in Ukrainian M270 and M142 launchers.[126]

Ukraine: Ukrainian Army (16) The United Kingdom, Norway, France,[121] Germany and Italy[122] provided more than ten systems to Ukraine in 2022.[36][123][124][125] In October 2023, the US donated ATACMS for use in Ukrainian M270 and M142 launchers.[126]

M270A2

[edit] United States: United States Army (840+151), 225 M270A1 and 160 M270A2 being delivered.[118] The first M270A2 launcher was delivered 9 July 2022.[127] GMLRS and ATACMS operational.[118]

United States: United States Army (840+151), 225 M270A1 and 160 M270A2 being delivered.[118] The first M270A2 launcher was delivered 9 July 2022.[127] GMLRS and ATACMS operational.[118]

Former operators

[edit]M270

[edit] Denmark: Royal Danish Army (12)

Denmark: Royal Danish Army (12) Netherlands: Royal Netherlands Army (23); retired from service in 2004; 1 displayed in a museum.

Netherlands: Royal Netherlands Army (23); retired from service in 2004; 1 displayed in a museum. Norway: Norwegian Army (12), put in storage in 2005.[128] Three donated to the United Kingdom to support the corresponding transfer of three British M270B1 MLRS to Ukraine.[129] Another 8 donated in May 2023.[130]

Norway: Norwegian Army (12), put in storage in 2005.[128] Three donated to the United Kingdom to support the corresponding transfer of three British M270B1 MLRS to Ukraine.[129] Another 8 donated in May 2023.[130] United States: United States Marine Corps replaced by M142 HIMARS.

United States: United States Marine Corps replaced by M142 HIMARS.

See also

[edit]- Launchers with the same ammunition pod as the M270:

- M142 HIMARS – (United States)

- K239 Chunmoo – (South Korea)

- T-122 Sakarya – (Turkey)

- Fajr-5 – (Iran)

- LAR-160 – (Israel)

- Astros II – (Brazil)

- Pinaka multi-barrel rocket launcher – (India)

- BM-21 – (Soviet Union)

- Fath-360 – (Iran)

- BM-30 Smerch – (Soviet Union)

- PHL-03 – (China)

- TOS-1 – (Soviet Union, Russia)

References

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Foss, Christopher F., ed. (2011). "Multiple Rocket Launchers". Jane's Armour and Artillery 2011–2012 (32nd ed.). London: Janes Information Group. pp. 1122–1127. ISBN 978-0710629609.

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Parsons, Dan (31 May 2022). "Ukraine To Get Guided Rockets, But Not Ones Able To Reach Far Into Russia (Updated)". The Drive.

- ^ "HIMARS price increase doesn't add up". 22 August 2023.

- ^ Bisht, Inder. "US Army Awards Lockheed $194M Multiple Launch Rocket System Contract". The Defense Post.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Hunnicutt 2015, p. 453.

- ^ "Lockheed Tests Improved GMLRS Rocket". Army technology. 8 November 2009.

- ^ "Ukraine war: UK to send Ukraine M270 multiple-launch rocket systems". 2022-06-06. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ "Long Live the King (of battle): The Return to Centrality of Artillery in Warfare and its Consequences on the Military Balance in Europe - Finabel". finabel.org. 2019-10-29. Retrieved 2024-01-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Miskimon, Christopher (30 October 2018). "The Multiple Launch Rocket System". Warfare History Network. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b U.S. Army Aviation and Missile Life Cycle Management Command. "MLRS". U.S. Army. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Hunnicutt 2015, p. 308–318.

- ^ "ODIN - OE Data Integration Network". odin.tradoc.army.mil. Retrieved 2024-04-25.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin's Extended-Range Rocket Proves Effective In Double Shot" (Press release). Dallas, Texas: Lockheed Martin. 7 March 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ PIke, John. "M270 Multiple Launch Rocket System – MLRS". FAS. Archived from the original on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ Hunnicutt 2015, pp. 448, 453.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zaloga, Steven J. (1995). "Variants". M2/M3 Bradley. London: Reed Consumer Books. pp. 43–45. ISBN 1-85532-538-1.

- ^ Hambling, David (30 May 2008). "After Cluster Bombs: Raining Nails". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017.

- ^ Foss, Christopher F., ed. (2011). "Multiple Rocket Launchers". Jane's Armour and Artillery 2011–2012 (32nd ed.). London: Janes Information Group. pp. 1128–1130. ISBN 978-0710629609.

- ^ "Guided MLRS Unitary Rocket Successfully Tested" Archived 2006-11-15 at the Wayback Machine, Microwave Journal, Vol. 49, No. 3 (March 2006), p. 39.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Lockheed Gets $16.6M to Convert MLRS Rockets, Asked to Speed Up GMLRS Production". Defense Industry Daily. 2 August 2006. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ "Precision Fires Rocket & Missile Systems". msl.army.mil. Archived from the original on 27 June 2015.

- ^ "Weapons Systems Handbook 2020-2021" (PDF). U.S. Army. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "Lockheed Tests Improved GMLRS Rocket". Army Technology. 2009-11-08. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ^ "Rollout MARS II und GMLRS Unitary" (in German). Bwb.org. 2012-07-26. Archived from the original on 2012-03-17. Retrieved 2012-08-06.

- ^ "Krauss Maffei Wegmann 155 mm 52 calibre Artillery Gun Module AGM Germany". Defense & Security Intelligence & Analysis IHS. Jane’s. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ "USA Moves to Update Its M270 Rocket Launchers". Defense industry daily. 2012-07-01. Archived from the original on 2013-12-22. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ Hamilton, Mr. John Andrew (3 August 2015). "Improved Multiple Launch Rocket System tested at White Sands Missile Range". Army.mil. Archived from the original on 16 April 2016.

- ^ Judson, Jen (5 March 2021). "US Army's extended-range guided rocket sees successful 80-kilometer test shot". Defense News. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Judson, Jen (30 March 2021). "Lockheed scores $1.1B contract to build US Army's guided rocket on heels of extended-range test". Defense News. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ^ Bisht, Inder Singh (4 September 2023). "Lockheed Demonstrates Doubling of HIMARS Munition Range". The Defense Post.

- ^ Extended range version of Army guided rocket enters production. Defense News. 26 June 2024.

- ^ "History for 6th Battalion, 27th Field Artillery (1960s to Present)". Military.com. Archived from the original on 2013-09-05. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ "C-1/27th FA MLRS". YouTube. 2009-11-26. Archived from the original on 2014-06-29. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ Fabian, Emanuel (11 October 2023). "IDF: Multiple rocket launcher used to target Hamas in Gaza for first time since 2006". The Times of Israel.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Marquardt, Alex; Bertrand, Natasha; Sciutto, Jim (26 May 2022). "US preparing to approve advanced long-range rocket system for Ukraine". CNN. Retrieved 27 May 2022.

- ^ Sabbagh, Dan (2022-05-31). "Biden will not supply Ukraine with long-range rockets that can hit Russia". The Guardian.

- ^ Basak, Saptarshi (2 June 2022). "What Is the M142 Himars That the US Is Supplying to Ukraine To Fight Russia?". The Quint.

- ^ Durbin, Adam (6 June 2022). "Ukraine war: UK to send Ukraine M270 multiple-launch rocket systems". BBC News.

- ^ Ahmedzade, Tural; Brown, David (11 August 2022). "What weapons are being given to Ukraine by the UK?". BBC News.

- ^ Fiorenza, Nicholas (19 September 2022). "Ukraine conflict: Germany supplies Dingo armoured vehicles and two more MRLs to Kyiv". Janes.

- ^ Altman, Howard (15 July 2022). "Ukraine Gets First M270 Multiple Launch Rocket Systems". The Drive/The Warzone.

- ^ "Mehrfachraketenwerfer in Ukraine eingetroffen". tagesschau.de (in German). 26 July 2022.

- ^ Sprenger, Sebastian (15 September 2022). "Under pressure, Germany pledges more military aid to Ukraine". Defense News.

- ^ Alkousaa, Riham; Siebold, Sabine (15 September 2022). "Germany says it will deliver two more multiple rocket launchers to Ukraine". Reuters.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Alex Marquardt; Natasha Bertrand; Zachary Cohen (2023-05-06). "Russia's jamming of US-provided rocket systems complicates Ukraine's war effort". CNN. Retrieved 2023-05-06.

- ^ "Bahrain – M270 Multiple Launch Rocket Systems (MLRS) Upgrade" (Press release). Defense Security Cooperation Agency. 24 March 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ Allison, George (2022-09-16). "Britain 'recapitalising' M270 missile launcher system". UK Defence Journal. Retrieved 2024-01-03.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Receives $45.3 Million Contract to Upgrade Finland's Precision Fires Capability". PR Newswire. Lockheed Martin. 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "MLRS Improved". Krauss-Maffei Wegmann. Archived from the original on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "MARS II / MLRS-E - KMW" (in German). Krauss-Maffei Wegmann. Archived from the original on 2022-07-28. Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Sagem's Sigma 30 navigation and pointing system chosen to modernize M270 Multiple Launch Rocket Systems for three European armies". Safran. Sagem. 18 Jan 2012. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Receives $362 Million Contract For Multiple Launch Rocket System Launcher (M270A2) Recapitalization". Lockheed Martin. 23 April 2019. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Colonel Joe Russo, CO 14 Marines (May 2018). "Long-Range Precision Fires" (PDF). Marine Corps Gazette: 40. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Jump up to: a b c d "United States Cluster Munition Ban Policy". Landmine and Cluster Munitions Monitor. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Weapon System Handbook" (PDF). Program Executive Office Missiles and Space. pp. 105–106. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Burdell, Clester (18 May 2018). "ANMC opens new rocket recycling facility". US Army. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ D'Ambrosio, Palma. "Destroying Cluster Munitions Stockpiles: the Italian Experience" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Dewitz, Christian (26 November 2015). "Letzte Streubomben der Bundeswehr vernichtet". Bundeswehr Journal. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Streubomben der Bundeswehr werden in der Uckermark zerstört". Lausitzer Rundschau. 12 July 2012. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Small Arms Survey 2013" (PDF). p. 195. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Weapon System Handbook" (PDF). Program Executive Office Missiles and Space. pp. 107–108. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j Turner, Paul E. "Precision Fires Rocket and Missile Systems" (PDF). US Army Precision Fires Rocket & Missile Systems Project Office. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Lindstrom, Kinsey. "Army celebrates production of 50,000th GMLRS rocket and its continued evolution". Program Executive Office Missiles and Space. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Korshak, Stefan (2023-02-04). "EXPLAINED: Ukraine to Get New Long-Range GLSDB Missiles – What Happens Next?". Get the Latest Ukraine News Today - KyivPost. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ "How Much GMLRS Missiles for HIMARS Cost: New Massive Contract with Finland Tells". Defense Express. 2022-11-03. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ Altman, Howard (2022-07-27). "Are There Enough Guided Rockets For HIMARS To Keep Up With Ukraine War Demand?". The Drive. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ Parsons, Dan (2022-05-31). "Ukraine To Get Guided Rockets, But Not Ones Able To Reach Far Into Russia (Updated)". The Drive. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ Judson, Jen (28 April 2023). "Lockheed wins $4.8B guided rockets contract". Defense News.

- ^ "Weapons Systems Handbook 2020-2021" (PDF). U.S. Army. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ "GMLRS: The Precision Fires Go-To Round". Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 22 May 2024. Retrieved 14 June 2024.

- ^ "Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System/Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System Alternative Warhead (GMLRS/GMLRS AW)" (PDF). Defense Acquisition Management Information Retrieval. p. 15. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Ukrainian Army Showcases New 90KM Range M31A1 GMLRS Projectile For HIMARS". Global Defense Corp. 2022-09-26. Retrieved 2023-05-07.

- ^ "Lockheed Tests Improved GMLRS Rocket". Army technology. 8 November 2009.

- ^ "Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System – Alternate Warhead (GMLRS-AW)" (PDF). The Office of the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Federal Register :: Request Access". unblock.federalregister.gov. Retrieved 2023-09-26.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System/Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System Alternative Warhead (GMLRS/GMLRS AW)" (PDF). Defense Acquisition Management Information Retrieval. p. 7. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "GMLRS Unitary Warhead". General Dynamics. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "M142 HIMARS Multiple Launch Rocket System". Military-Today.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2008. Retrieved 2023-05-14.

- ^ "Weapon System Handbook" (PDF). Program Executive Office Missiles and Space. pp. 111–112. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Muczyński, Rafał (30 November 2019). "Europejski pocisk dla M270 MLRS". MILMAG (in Polish). Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ Freedberg Jr, Sydney J. (11 October 2018). "Army Building 1,000-Mile Supergun". Breaking Defense. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018.

- ^ Judson, Jen (13 October 2020). "Army, Lockheed prep for first extended-range guided rocket test firing". Defense News. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Mission Success: Lockheed Martin's Extended-Range Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System Soars In Flight Test". Lockheed Martin. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- ^ "Finland becomes first extended range GMLRS rocket customer". Defense Brief. 12 February 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) Modification (MOD)" (PDF). The Office of the Director, Operational Test and Evaluation. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Keller, John (30 July 2021). "Lockheed Martin to upgrade weapons payloads and navigation and guidance on ATACMS battlefield munitions". Military+Aerospace Electronics. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Weapon System Handbook" (PDF). Program Executive Office Missiles and Space. pp. 115–116. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Weapon System Handbook" (PDF). Program Executive Office Missiles and Space. pp. 117–118. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 August 2022. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- ^ "Precision-Guided Munitions: Background and Issues for Congress" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. p. 22. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ "Precision Strike Missile (PrSM)". Lockheed Martin. 22 December 2021. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Artillery and Air Defence". British Army. 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Upgrades to Multiple Launch Rocket Systems Strengthen Deep Fires Capability". British Army. 12 October 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "Gabriel Mollinelli". X (formerly Twitter). 14 September 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Land Precision Strike - Think Defence". www.thinkdefence.co.uk. 2022-12-31. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Land Precision Strike | Innovation". MBDA. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "The Science Inside 2022". GOV.UK. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "Eurosatory 2024: MBDA and Safran team up on Thundart guided artillery rocket". Janes. Janes Information Services. 19 June 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2024.

- ^ Eshel, Tamir (24 April 2012). "GMLRS to Get a New Warhead". Defense Update. Archived from the original on 2 May 2014.

- ^ Hamilton, John Andrew (2 September 2014). "Army tests safer warhead". armytechnology.armylive.dodlive.mil. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014.

- ^ "Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System – Alternate Warhead (GMLRS-AW) M30E1" (PDF). dote.osd.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2017.

- ^ "The new M30A1 GMLRS Alternate Warhead to replace cluster bombs for US Army Central". Army Recognition. 16 January 2017.

- ^ "US Army searches for cluster munitions alternatives". Dmilt.com. Archived from the original on 2014-02-02. Retrieved 2013-10-23.

- ^ "Altenative GMLRS Warhead Completes Third Successful Fight Test". deagel.com. 23 October 2013. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin GMLRS Alternative Warhead Logs Successful Flight-Test Series, Shifts To Next Testing Phase". Lockheed Martin. 16 April 2014. Archived from the original on 26 November 2022.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Completes Successful Operational Flight Tests of GMLRS Alternative Warhead". Deagel.com. 28 July 2014. Archived from the original on 29 July 2014.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin GMLRS Alternative Warhead Gets First Order". MarketWatch. 15 September 2015. Archived from the original on 19 November 2015.

- ^ "SPECIFICATIONS - MLRS MULTIPLE LAUNCH ROCKET SYSTEM, USA". army-technology.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008. [unreliable source?]

- ^ "227mm Multiple Launched Rocket System (MLRS)". British Army. Archived from the original on August 23, 2004.

- ^ Parsons, Dan (31 May 2022). "Ukraine to Get Guided Rockets, but Not Ones Able to Reach Far into Russia (Updated)".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "ATACMS". Deagel. Archived from the original on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ "Upgrade of the MLRS fleet to ensure long-range fires capacity" (Press release). Maavoimat.fi. 2023-12-22. Retrieved 2023-12-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "La DGA commande 13 Lance-roquettes unitaires (LRU)". Défense. Direction générale de l'armement. 7 Oct 2011. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Mackenzie, Christina (17 June 2024). "Rheinmetall, Lockheed unveil GMARS, in talks with European customers: Exec". Breaking Defense. Retrieved 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Trade Registers". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2016.

- ^ "M270 MLRS Report between 1993 and 2014". Deagel. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ "MLRS (Multiple Launch Rocket System), United States of America". Army technology. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "MLRS® M270 Series Launchers" (PDF). Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- ^ Allison, George (2024-05-03). "Britain confirms plans to double rocket artillery fleet". Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ Thomas, Richard (12 October 2022). "UK dips into booming global artillery market with M270A2 upgrade". Army Technology. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

- ^ "La France annonce de nouvelles livraisons d'armes à l'Ukraine". Le Monde.fr. 21 November 2022.

- ^ Biloslavo, Fausto (3 January 2023). "Quei super lanciarazzi sono (anche) italiani. Precisissimi e letali, fanno tremare il Cremlino". Il Giornale (in Italian).

- ^ "[image] Deutschland will angeblich Mehrfachraketenwerfer in die Ukraine Liefern" [Germany reportedly wants to supply multiple rocket launchers to Ukraine] (in German). Der Spiegel – via postimg.[better source needed]

- ^ "Великобритания вслед за Штатами объявила о поставках реактивных систем в Украину". The Uk.

- ^ "Minister of Defence of Ukraine". Twitter. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ^ "US-supplied ATACMS enter the Ukraine war". Reuters. 2023-10-19. Retrieved 2023-10-21.

- ^ "Lockheed Martin Delivers First Modernized M270A2 to U.S. Army". Lockheed Martin. 12 July 2022.

- ^ "Hærens storslegge i hvilestilling". NRK (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. Retrieved 2017-02-10.

- ^ "Norway and the United Kingdom donate long range rocket artillery to Ukraine". Regjeringen. Norwegian Government. 29 June 2022.

- ^ "Noreg støttar Ukraina med langtrekkjande artilleri og radarar". regjeringen.no (Norwegian Government). 18 May 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Hunnicutt, Richard Pearce (15 September 2015) [1999]. "The Fighting Vehicle System Carrier". Bradley: A History of American Fighting and Support Vehicles. Battleboro, VT: Echo Point Books & Media. pp. 308–318. ISBN 978-1-62654-153-5.