Lüshi Chunqiu

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2016) |

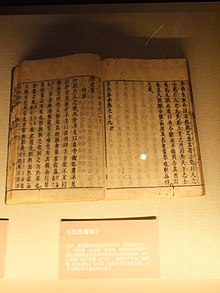

An Edo period (1603–1868) edition | |

| Author | Lü Buwei |

|---|---|

| Original title | 呂氏春秋 |

| Language | Chinese |

| Genre | Chinese classics |

| Publication place | China |

| Lüshi chunqiu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 呂氏春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 吕氏春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Mr. Lü's Spring and Autumn [Annals]" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Lüshi Chunqiu (simplified Chinese: 吕氏春秋; traditional Chinese: 呂氏春秋; lit. 'Lü's Spring and Autumn'), also known in English as Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals,[1][2] is an encyclopedic Chinese classic text compiled around 239 BC under the patronage of late pre-imperial Qin Chancellor Lü Buwei. In the evaluation of Michael Loewe, "The Lü shih ch'un ch'iu is unique among early works in that it is well organized and comprehensive, containing extensive passages on such subjects as music and agriculture, unknown elsewhere." One of the longest early texts, it extends to over 100,000 words.[3]

Combining ideas from many different 'schools', the work is traditionally classified as 'Syncretist', although there was no school that called itself Syncretist.[4]

Background

[edit]The Shiji (chap. 85, p. 2510) biography of Lü Buwei has the earliest information about the Lüshi Chunqiu. Lü was a successful merchant from Handan who befriended King Zhuangxiang of Qin. The king's son Zheng, who the Shiji suggests was actually Lü's son, eventually became the first emperor Qin Shi Huang in 221 BC. When Zhuangxiang died in 247 BC, Lü was made regent for the 13-year-old Zheng. In order to establish Qin as the intellectual center of China, Lü "recruited scholars, treating them generously so that his retainers came to number three thousand".[5] In 239 BC, he, in the words of the Shiji:[6]

... ordered that his retainers write down all that they had learned and assemble their theses into a work consisting of eight "Examinations", six "Discourses", and twelve "Almanacs", totaling more than 200,000 words.

According to the Shiji, Lü exhibited the completed text at the city gate of Xianyang, capital of Qin, and above it a notice offering a thousand measures of gold to any traveling scholar who could add or subtract even a single word.

The Hanshu Yiwenzhi lists the Lüshi Chunqiu as belonging to the Zajia (杂家; 雜家; 'mixed school'), within the philosophers' domain (諸子略), or Hundred Schools of Thought. Although this text is frequently characterized as "syncretic", "eclectic", or "miscellaneous", it was a cohesive summary of contemporary philosophical thought, including Legalism, Confucianism, Mohism, and Daoism.

Contents

[edit]The title uses chunqiu (春秋; spring and autumn) to mean 'annals; chronicle' in a reference to the Confucianist Spring and Autumn Annals, which chronicles the State of Lu history from 722–481 BC.

The text comprises 26 juan (卷; 'scrolls', 'books') in 160 pian (篇; 'sections'), and is divided into three major parts.

- The Ji (紀; 'Almanacs') comprises books 1–12, which corresponds to the months of the year, and lists appropriate seasonal activities to ensure that the state runs smoothly. This part, which was copied as the Liji chapter Yueling, takes many passages from other texts, often without attribution.

- The Lan (覧; 'Examinations') comprises books 13–20, which each have 8 sections. This is the longest and most eclectic part, giving quotations from many early texts, some no longer extant.

- The Lun (論; 'Discourses') comprises books 21–26, which mostly deals with rulership, except for the final four sections about agriculture. This part resembles the Lan in composition.

Integrity of the text

[edit]The composition's features, measure of completeness (i.e. the veracity of the Shiji account) and possible corruption of the original Annals have been subjects of scholarly attention. It has been mentioned that the Almanacs have much greater integrity and thematic organization than the other two parts of the text.

The Yuda (諭大) chapter of the Examinations, for example, contains text almost identical to the Wuda (務大) chapter of the Discourses, though in the first case it is ascribed to Jizi (季子), and in the second to Confucius.

Major positions

[edit]Admitting the difficulties of summarizing the Lüshi Chunqiu, John Knoblock and Jeffrey Riegel list 18 major points:

- Affirmation of self-cultivation and impartiality

- Rejection of hereditary ruler over the empire

- Stupidity as the cause of hereditary rule

- Need for government to honor the concerns of the people

- The central importance of learning and teachers

- Support and admiration for learning as the basis of rule

- Non-assertion on the part of the ruler

- Primary task for a ruler is to select his ministers

- Need for a ruler to trust the expertise of his advisers

- Need for a ruler to practice quiescence

- The attack on Qin practices

- Just warfare

- Respect for civil arts

- Emphasis on agriculture

- Facilitating trade and commerce

- Encouraging economy and conservation

- Lightening of taxes and duties

- Emphasis on filial piety and loyalty.[7]

The Lüshi chunqiu is an invaluable compendium of early Chinese thought and civilization.

Correction bounty

[edit]The Shiji tells that after Lü Buwei presented the finished Lüshi Chunqiu for the public at the gate of Xianyang and announced that anyone could correct the book's content would be awarded 1000 taels of gold for every corrected word. This event lead to the Chinese idiom "One word [is worth] a thousand gold" (一字千金).

None of the contemporary scholars pointed out any mistakes in the work, although later scholars managed to detect a number of them. It is believed that Lü's contemporaries were able to detect the book's inaccuracies, but none dared to openly criticize a powerful figure like him.

Reception

[edit]Scholar Liang Qichao (1873–1929) stated: "This book, through the course of two thousand years, has had no deletions nor corruptions. Moreover, it has the excellent commentary of Gao You. Truly it is the most perfect and easily read work among the ancient books."[8] Liang's position, mildly criticized afterwards,[by whom?] was dictated by the lack of canonical status ascribed to the book.

References

[edit]- Footnotes

- ^ Sellman, James D. (2002), Timing and Rulership in Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals, Albany: State University of New York Press.

- ^ Sellman, James D. (1998), "Lushi Chunqiu", Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Taylor & Francis, doi:10.4324/9780415249126-G057-1.

- ^ Loewe & Carson (1993:324).

- ^ Lundahl 1992. p130, Xiaogan Liu 1994, p.xvi

- ^ Knoblock and Riegel (2000:13)

- ^ Knoblock and Riegel (2000:14)

- ^ Knoblock and Riegel (2000:46–54)

- ^ Stephen W. Durrant, "The Cloudy Mirror", p.80

- Works cited

- Lundahl, Bertil (1992). Lundahl, Bertil (ed.). Han Fei Zi: The Man and the Work. Institute of Oriental Languages, Stockholm University. ISBN 9789171530790.

- Carson, Michael; Loewe, Michael (1993). "Lü shih ch'un ch'iu 呂氏春秋". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley. pp. 324–30. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Knoblock, John and Riegel, Jeffrey. 2000. The Annals of Lü Buwei: A Complete Translation and Study. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-3354-6.

- Sellmann, James D. 2002. Timing and Rulership in Master Lü's Spring and Autumn Annals (Lüshi chunqiu). Albany: State University of New York Press.

External links

[edit]- 呂氏春秋, complete text in Chinese

- Lüshi chunqiu 呂氏春秋, ChinaKnowledge entry