Abdominal pain

| Abdominal pain | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Stomach ache, tummy ache, belly ache, belly pain, gastralgia, stomach pain |

| |

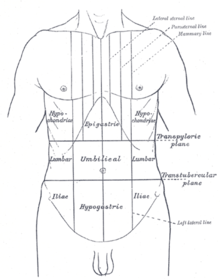

| Abdominal pain can be characterized by the region it affects. | |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, general surgery |

| Causes | Serious: Appendicitis, perforated stomach ulcer, pancreatitis, ruptured diverticulitis, ovarian torsion, volvulus, ruptured aortic aneurysm, lacerated spleen or liver, ischemic colitis, ischaemic myocardial conditions[1] Common: Gastroenteritis, irritable bowel syndrome[2] |

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues. Since the abdomen contains most of the body's vital organs, it can be an indicator of a wide variety of diseases. Given that, approaching the examination of a person and planning of a differential diagnosis is extremely important.[3]

Common causes of pain in the abdomen include gastroenteritis and irritable bowel syndrome.[2] About 15% of people have a more serious underlying condition such as appendicitis, leaking or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, diverticulitis, or ectopic pregnancy.[2] In a third of cases, the exact cause is unclear.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The onset of abdominal pain can be abrupt, quick, or gradual. Sudden onset pain happens in a split second. Rapidly onset pain starts mild and gets worse over the next few minutes. Pain that gradually intensifies only after several hours or even days has passed is referred to as gradual onset pain.[4]

One can describe abdominal pain as either continuous or sporadic and as cramping, dull, or aching. The characteristic of cramping abdominal pain is that it comes in brief waves, builds to a peak, and then abruptly stops for a period during which there is no more pain. The pain flares up and off periodically. The most common cause of persistent dull or aching abdominal pain is edema or distention of the wall of a hollow viscus. A dull or aching pain may also be felt due to a stretch in the liver and spleen capsules.[4]

Causes

[edit]The most frequent reasons for abdominal pain are gastroenteritis (13%), irritable bowel syndrome (8%), urinary tract problems (5%), inflammation of the stomach (5%) and constipation (5%). In about 30% of cases, the cause is not determined. About 10% of cases have a more serious cause including gallbladder (gallstones or biliary dyskinesia) or pancreas problems (4%), diverticulitis (3%), appendicitis (2%) and cancer (1%).[2] More common in those who are older, ischemic colitis,[5] mesenteric ischemia, and abdominal aortic aneurysms are other serious causes.[6]

Acute abdomen

[edit]Acute abdomen is a condition where there is a sudden onset of severe abdominal pain requiring immediate recognition and management of the underlying cause.[7] The underlying cause may involve infection, inflammation, vascular occlusion or bowel obstruction.[7]

The pain may elicit nausea and vomiting, abdominal distention, fever and signs of shock.[7] A common condition associated with acute abdominal pain is appendicitis.[8] Here is a list of acute abdomen causes:

Surgical causes[edit] |

Source:[7] Inflammatory[edit]

Mechanical[edit]

Vascular[edit]

Source:[9]

|

|---|---|

Medical causes[edit] |

Source:[7] Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). |

Gynecological causes[edit] |

Source:[11] Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) and abscess. Hemorrhagic ovarian cyst. Adnexal or ovarian torsion. |

By system

[edit]A more extensive list includes the following:[citation needed]

- Gastrointestinal

- GI tract

- Inflammatory: gastroenteritis, appendicitis, gastritis, esophagitis, diverticulitis, Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, microscopic colitis

- Obstruction: hernia, intussusception, volvulus, post-surgical adhesions, tumors, severe constipation, hemorrhoids

- Vascular: embolism, thrombosis, hemorrhage, sickle cell disease, abdominal angina, blood vessel compression (such as celiac artery compression syndrome), superior mesenteric artery syndrome, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome

- Digestive: peptic ulcer, lactose intolerance, celiac disease, food allergies, indigestion

- Glands

- Bile system

- Inflammatory: cholecystitis, cholangitis

- Obstruction: cholelithiasis

- Liver

- Inflammatory: hepatitis, liver abscess

- Pancreatic

- Inflammatory: pancreatitis

- Bile system

- GI tract

- Renal and urological

- Inflammation: pyelonephritis, bladder infection

- Obstruction: kidney stones, urolithiasis, urinary retention

- Vascular: left renal vein entrapment

- Gynaecological or obstetric

- Inflammatory: pelvic inflammatory disease

- Mechanical: ovarian torsion

- Endocrinological: menstruation, Mittelschmerz

- Tumors: endometriosis, fibroids, ovarian cyst, ovarian cancer

- Pregnancy: ruptured ectopic pregnancy, threatened abortion

- Abdominal wall

- muscle strain or trauma

- muscular infection

- neurogenic pain: herpes zoster, radiculitis in Lyme disease, abdominal cutaneous nerve entrapment syndrome (ACNES), tabes dorsalis

- Referred pain

- from the thorax: pneumonia, pulmonary embolism, ischemic heart disease, pericarditis

- from the spine: radiculitis

- from the genitals: testicular torsion

- Metabolic disturbance

- uremia, diabetic ketoacidosis, porphyria, C1-esterase inhibitor deficiency, adrenal insufficiency, lead poisoning, black widow spider bite, narcotic withdrawal

- Blood vessels

- Immune system

- Idiopathic

- irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) (affecting up to 20% of the population, IBS is the most common cause of recurrent and intermittent abdominal pain)

By location

[edit]The location of abdominal pain can provide information about what may be causing the pain. The abdomen can be divided into four regions called quadrants. Locations and associated conditions include:[12][13]

- Diffuse

- Epigastric

- Heart: myocardial infarction, pericarditis

- Stomach: gastritis, stomach ulcer, stomach cancer

- Pancreas: pancreatitis, pancreatic cancer

- Intestinal: duodenal ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis

- Right upper quadrant

- Liver: hepatomegaly, fatty liver, hepatitis, liver cancer, abscess

- Gallbladder and biliary tract: inflammation, gallstones, worm infection, cholangitis

- Colon: bowel obstruction, functional disorders, gas accumulation, spasm, inflammation, colon cancer

- Other: pneumonia, Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome

- Left upper quadrant

- Splenomegaly

- Colon: bowel obstruction, functional disorders, gas accumulation, spasm, inflammation, colon cancer

- Peri-umbilical (the area around the umbilicus, i.e., the belly button)

- Appendicitis

- Pancreatitis

- Inferior myocardial infarction

- Peptic ulcer

- Diabetic ketoacidosis

- Vascular: aortic dissection, aortic rupture

- Bowel: mesenteric ischemia, Celiac disease, inflammation, intestinal spasm, functional disorders, small bowel obstruction

- Lower abdominal pain

- Right lower quadrant

- Colon: intussusception, bowel obstruction, appendicitis (McBurney's point)

- Renal: kidney stone (nephrolithiasis), pyelonephritis

- Pelvic: cystitis, bladder stone, bladder cancer, pelvic inflammatory disease, pelvic pain syndrome

- Gynecologic: endometriosis, intrauterine pregnancy, ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cyst, ovarian torsion, fibroid (leiomyoma), abscess, ovarian cancer, endometrial cancer

- Left lower quadrant

- Bowel: diverticulitis, sigmoid colon volvulus, bowel obstruction, gas accumulation, Toxic megacolon

- Right low back pain

- Liver: hepatomegaly

- Kidney: kidney stone (nephrolithiasis), complicated urinary tract infection

- Left low back pain

- Spleen

- Kidney: kidney stone (nephrolithiasis), complicated urinary tract infection

- Low back pain

- Kidney pain (kidney stone, kidney cancer, hydronephrosis)

- Ureteral stone pain

Mechanism

[edit]| Region | Blood supply[14] | Innervation[15] | Structures[14] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Foregut | Celiac artery | T5 - T9 | Pharynx

Proximal duodenum |

| Midgut | Superior mesenteric artery | T10 – T12 | Distal duodenum

Proximal transverse colon |

| Hindgut | Inferior mesenteric artery | L1 – L3 | Distal transverse colon

Superior anal canal |

Abdominal pain can be referred to as visceral pain or peritoneal pain. The contents of the abdomen can be divided into the foregut, midgut, and hindgut.[14] The foregut contains the pharynx, lower respiratory tract, portions of the esophagus, stomach, portions of the duodenum (proximal), liver, biliary tract (including the gallbladder and bile ducts), and the pancreas.[14] The midgut contains portions of the duodenum (distal), cecum, appendix, ascending colon, and first half of the transverse colon.[14] The hindgut contains the distal half of the transverse colon, descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum, and superior anal canal.[14]

Each subsection of the gut has an associated visceral afferent nerve that transmits sensory information from the viscera to the spinal cord, traveling with the autonomic sympathetic nerves.[16] The visceral sensory information from the gut traveling to the spinal cord, termed the visceral afferent, is non-specific and overlaps with the somatic afferent nerves, which are very specific.[17] Therefore, visceral afferent information traveling to the spinal cord can present in the distribution of the somatic afferent nerve; this is why appendicitis initially presents with T10 periumbilical pain when it first begins and becomes T12 pain as the abdominal wall peritoneum (which is rich with somatic afferent nerves) is involved.[17]

Diagnosis

[edit]A thorough patient history and physical examination is used to better understand the underlying cause of abdominal pain.

The process of gathering a history may include:[18]

- Identifying more information about the chief complaint by eliciting a history of present illness; i.e. a narrative of the current symptoms such as the onset, location, duration, character, aggravating or relieving factors, and temporal nature of the pain. Identifying other possible factors may aid in the diagnosis of the underlying cause of abdominal pain, such as recent travel, recent contact with other ill individuals, and for females, a thorough gynecologic history.

- Learning about the patient's past medical history, focusing on any prior issues or surgical procedures.

- Clarifying the patient's current medication regimen, including prescriptions, over-the-counter medications, and supplements.

- Confirming the patient's drug and food allergies.

- Discussing with the patient any family history of disease processes, focusing on conditions that might resemble the patient's current presentation.

- Discussing with the patient any health-related behaviors (e.g. tobacco use, alcohol consumption, drug use, and sexual activity) that might make certain diagnoses more likely.

- Reviewing the presence of non-abdominal symptoms (e.g., fever, chills, chest pain, shortness of breath, vaginal bleeding) that can further clarify the diagnostic picture.

- Using Carnett's sign to differentiate between visceral pain and pain originating in the muscles of the abdominal wall.[19]

After gathering a thorough history, one should perform a physical exam in order to identify important physical signs that might clarify the diagnosis, including a cardiovascular exam, lung exam, thorough abdominal exam, and for females, a genitourinary exam.[18]

Additional investigations that can aid diagnosis include:[20]

- Blood tests including complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, electrolytes, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, troponin I, and for females, a serum pregnancy test.

- Urinalysis

- Imaging including chest and abdominal X-rays

- Electrocardiogram

If diagnosis remains unclear after history, examination, and basic investigations as above, then more advanced investigations may reveal a diagnosis. Such tests include:[20]

- Computed tomography of the abdomen/pelvis

- Abdominal or pelvic ultrasound

- Endoscopy or colonoscopy

Management

[edit]The management of abdominal pain depends on many factors, including the etiology of the pain. Some dietary changes that some may participate in are: resting after a meal, chewing food completely and slowly, and avoiding stressful and high excitement situations after a meal. Some at home strategies like these can avoid future abdominal issues, resulting in the need of professional assistance.[21] In the emergency department, a person presenting with abdominal pain may initially require IV fluids due to decreased intake secondary to abdominal pain and possible emesis or vomiting.[22] Treatment for abdominal pain includes analgesia, such as non-opioid (ketorolac) and opioid medications (morphine, fentanyl).[22] Choice of analgesia is dependent on the cause of the pain, as ketorolac can worsen some intra-abdominal processes.[22] Patients presenting to the emergency department with abdominal pain may receive a "GI cocktail" that includes an antacid (examples include omeprazole, ranitidine, magnesium hydroxide, and calcium chloride) and lidocaine.[22] After addressing pain, there may be a role for antimicrobial treatment in some cases of abdominal pain.[22] Butylscopolamine (Buscopan) is used to treat cramping abdominal pain with some success.[23] Surgical management for causes of abdominal pain includes but is not limited to cholecystectomy, appendectomy, and exploratory laparotomy.[citation needed]

Emergencies

[edit]Below is a brief overview of abdominal pain emergencies.

| Condition | Presentation | Diagnosis | Management |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appendicitis[24] | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fever

Periumbilical pain, migrates to RLQ |

Clinical (history and physical exam)

Abdominal CT |

Patient made NPO (nothing by mouth)

IV fluids as needed General surgery consultation, possible appendectomy Antibiotics Pain control |

| Cholecystitis[24] | Abdominal pain (RUQ, radiates epigastric), nausea, vomiting, fever, Murphy's sign | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging (RUQ ultrasound) Labs (leukocytosis, transamintis, hyperbilirubinemia) |

Patient made NPO (nothing by mouth)

IV fluids as needed General surgery consultation, possible cholecystectomy Antibiotics Pain, nausea control |

| Acute pancreatitis[24] | Abdominal pain (sharp epigastric, shooting to back), nausea, vomiting | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Labs (elevated lipase) Imaging (abdominal CT, ultrasound) |

Patient made NPO (nothing by mouth)

IV fluids as needed Pain, nausea control Possibly consultation of general surgery or interventional radiology |

| Bowel obstruction[24] | Abdominal pain (diffuse, crampy), bilious emesis, constipation | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging (abdominal X-ray, abdominal CT) |

Patient made NPO (nothing by mouth)

IV fluids as needed Nasogastric tube placement General surgery consultation Pain control |

| Upper GI bleed[24] | Abdominal pain (epigastric), hematochezia, melena, hematemesis, hypovolemia | Clinical (history & physical exam, including digital rectal exam)

Labs (complete blood count, coagulation profile, transaminases, stool guaiac) |

Aggressive IV fluid resuscitation

Blood transfusion as needed Medications: proton pump inhibitor, octreotide Stable patient: observation Unstable patient: consultation (general surgery, gastroenterology, interventional radiology) |

| Lower GI bleed[24] | Abdominal pain, hematochezia, melena, hypovolemia | Clinical (history and physical exam, including digital rectal exam)

Labs (complete blood count, coagulation profile, transaminases, stool guaiac) |

Aggressive IV fluid resuscitation

Blood transfusion as needed Medications: proton pump inhibitor Stable patient: observation Unstable patient: consultation (general surgery, gastroenterology, interventional radiology) |

| Perforated Viscous[24] | Abdominal pain (sudden onset of localized pain), abdominal distension, rigid abdomen | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging (abdominal X-ray or CT showing free air) Labs (complete blood count) |

Aggressive IV fluid resuscitation

General surgery consultation Antibiotics |

| Volvulus[24] | Sigmoid colon volvulus: Abdominal pain (>2 days, distention, constipation)

Cecal volvulus: Abdominal pain (acute onset), nausea, vomiting |

Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging (abdominal X-ray or CT) |

Sigmoid: Gastroenterology consultation (flexibile sigmoidoscopy)

Cecal: General surgery consultation (right hemicolectomy) |

| Ectopic pregnancy[24] | Abdominal and pelvic pain, bleeding

If ruptured ectopic pregnancy, the patient may present with peritoneal irritation and hypovolemic shock |

Clinical (history and physical exam)

Labs: complete blood count, urine pregnancy test followed with quantitative blood beta-hCG Imaging: transvaginal ultrasound |

If patient is unstable: IV fluid resuscitation, urgent obstetrics and gynecology consultation

If patient is stable: continue diagnostic workup, establish OBGYN follow-up |

| Abdominal aortic aneurysm[24] | Abdominal pain, flank pain, back pain, hypotension, pulsatile abdominal mass | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging: Ultrasound, CT angiography, MRA/magnetic resonance angiography |

If patient is unstable: IV fluid resuscitation, urgent surgical consultation

If patient is stable: admit for observation |

| Aortic dissection[24] | Abdominal pain (sudden onset of epigastric or back pain), hypertension, new aortic murmur | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging: Chest X-ray (showing widened mediastinum), CT angiography, MRA, transthoracic echocardiogram/TTE, transesophageal echocardiogram/TEE |

IV fluid resuscitation

Blood transfusion as needed (obtain type and cross) Medications: reduce blood pressure (sodium nitroprusside plus beta blocker or calcium channel blocker) Surgery consultation |

| Liver injury[24] | After trauma (blunt or penetrating), abdominal pain (RUQ), right rib pain, right flank pain, right shoulder pain | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging: FAST examination, CT of abdomen and pelvis |

Resuscitation (advanced trauma life support) with IV fluids (crystalloid) and blood transfusion

If patient is unstable: general or trauma surgery consultation with subsequent exploratory laparotomy |

| Splenic injury[24] | After trauma (blunt or penetrating), abdominal pain (LUQ), left rib pain, left flank pain | Clinical (history and physical exam)

Imaging: FAST examination, CT of abdomen and pelvis |

Resuscitation (advanced trauma life support) with IV fluids (crystalloid) and blood transfusion

If patient is unstable: general or trauma surgery consultation with subsequent exploratory laparotomy and possible splenectomy If patient is stable: medical management, consultation of interventional radiology for possible arterial embolization |

Outlook

[edit]One well-known aspect of primary health care is its low prevalence of potentially dangerous abdominal pain causes. Patients with abdominal pain have a higher percentage of unexplained complaints (category "no diagnosis") than patients with other symptoms (such as dyspnea or chest pain).[25] Most people who suffer from stomach pain have a benign issue, like dyspepsia.[26] In general, it is discovered that 20% to 25% of patients with abdominal pain have a serious condition that necessitates admission to an acute care hospital.[27]

Epidemiology

[edit]Abdominal pain is the reason about 3% of adults see their family physician.[2] Rates of emergency department (ED) visits in the United States for abdominal pain increased 18% from 2006 through to 2011. This was the largest increase out of 20 common conditions seen in the ED. The rate of ED use for nausea and vomiting also increased 18%.[28]

Special populations

[edit]Geriatrics

[edit]More time and resources are used on older patients with abdominal pain than on any other patient presentation in the emergency department (ED).[29] Compared to younger patients with the same complaint, their length of stay is 20% longer, they need to be admitted almost half the time, and they need surgery 1/3 of the time.[30]

Age does not reduce the total number of T cells, but it does reduce their functionality. The elderly person's ability to fight infection is weakened as a result.[31] Additionally, they have changed the strength and integrity of their skin and mucous membranes, which are physical barriers to infection. It is well known that older patients experience altered pain perception.[32]

The challenge of obtaining a sufficient history from an elderly patient can be attributed to multiple factors. Reduced memory or hearing could make the issue worse. It is common to encounter stoicism combined with a fear of losing one's independence if a serious condition is discovered. Changes in mental status, whether acute or chronic, are common.[33]

Pregnancy

[edit]Unique clinical challenges arise when pregnant women experience abdominal pain. First off, there are many possible causes of abdominal pain during pregnancy. These include intraabdominal diseases that arise incidentally during pregnancy as well as obstetric or gynecologic disorders associated with pregnancy. Secondly, pregnancy modifies the natural history and clinical manifestation of numerous abdominal disorders. Third, pregnancy modifies and limits the diagnostic assessment. For instance, concerns about fetal safety during pregnancy are raised by invasive exams and radiologic testing. Fourth, while receiving therapy during pregnancy, the mother's and the fetus' interests need to be taken into account.[34]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Patterson JW, Dominique E (14 November 2018). "Acute Abdomenal". StatPearls. PMID 29083722.

- ^ a b c d e f Viniol A, Keunecke C, Biroga T, Stadje R, Dornieden K, Bösner S, et al. (October 2014). "Studies of the symptom abdominal pain—a systematic review and meta-analysis". Family Practice. 31 (5): 517–29. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmu036. PMID 24987023.

- ^ "differential diagnosis". Merriam-Webster (Medical dictionary). Retrieved 30 December 2014.

- ^ a b Sherman R (1990). Abdominal Pain. Butterworths. ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4. PMID 21250252. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Hung A, Calderbank T, Samaan MA, Plumb AA, Webster G (1 January 2021). "Ischaemic colitis: practical challenges and evidence-based recommendations for management". Frontline Gastroenterology. 12 (1): 44–52. doi:10.1136/flgastro-2019-101204. ISSN 2041-4137. PMC 7802492. PMID 33489068.

- ^ Spangler R, Van Pham T, Khoujah D, Martinez JP (2014). "Abdominal emergencies in the geriatric patient". International Journal of Emergency Medicine. 7: 43. doi:10.1186/s12245-014-0043-2. PMC 4306086. PMID 25635203.

- ^ a b c d e Patterson JW, Kashyap S, Dominique E (2023), "Acute Abdomen", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29083722, retrieved 23 September 2023

- ^ "Appendicitis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Arendt-Nielsen L, Svensson P (March 2001). "Referred Muscle Pain: Basic and Clinical Findings". The Clinical Journal of Pain. 17 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1097/00002508-200103000-00003. ISSN 0749-8047. PMID 11289083.

- ^ Collantes Celador E, Rudiger J, Tameem A, eds. (2022). Essential Notes in Pain Medicine (1st ed.). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/med/9780198799443.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-879944-3.

- ^ Burnett LS (April 1988). "Gynecologic causes of the acute abdomen". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 68 (2): 385–398. doi:10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44484-1. ISSN 0039-6109. PMID 3279553.

- ^ Masters P (2015). IM Essentials. American College of Physicians. ISBN 978-1-938921-09-4.

- ^ LeBlond RF (2004). Diagnostics. US: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. ISBN 978-0-07-140923-0.

- ^ a b c d e f Moore KL (2016). "11". The Developing Human Tenth Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, Inc. pp. 209–240. ISBN 978-0-323-31338-4.

- ^ Hansen JT (2019). "4: Abdomen". Netter's Clinical Anatomy, 4e. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. pp. 157–231. ISBN 978-0-323-53188-7.

- ^ Drake RL, Vogl AW, Mitchell AW (2015). "4: Abdomen". Gray's Anatomy For Students (Third ed.). Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. pp. 253–420. ISBN 978-0-7020-5131-9.

- ^ a b Neumayer L, Dangleben DA, Fraser S, Gefen J, Maa J, Mann BD (2013). "11: Abdominal Wall, Including Hernia". Essentials of General Surgery, 5e. Baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer Health.

- ^ a b Bickley L (2016). Bates' Guide to Physical Examination & History Taking. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-1-4698-9341-9.

- ^ Karen M. Myrick, Laima Karosas (6 December 2019). Advanced Health Assessment and Differential Diagnosis: Essentials for Clinical Practice. Springer Publishing Company. p. 250. ISBN 978-0-8261-6255-7.

- ^ a b Cartwright SL, Knudson MP (April 2008). "Evaluation of acute abdominal pain in adults". American Family Physician. 77 (7): 971–8. PMID 18441863.

- ^ "Indigestion: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 2 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Mahadevan SV. Essentials of Family Medicine 6e. p. 149.

- ^ Tytgat GN (2007). "Hyoscine butylbromide: a review of its use in the treatment of abdominal cramping and pain". Drugs. 67 (9): 1343–57. doi:10.2165/00003495-200767090-00007. PMID 17547475. S2CID 46971321.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Sherman SC, Cico SJ, Nordquist E, Ross C, Wang E (2016). Atlas of Clinical Emergency Medicine. Wolters Kluwer. ISBN 978-1-4511-8882-0.

- ^ A V, C K, T B, R S, K D, S B, et al. (2014). "Studies of the symptom abdominal pain—a systematic review and meta-analysis". Family Practice. 31 (5). Fam Pract: 517–529. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmu036. ISSN 1460-2229. PMID 24987023.

- ^ Gulacti U, Arslan E, Ooi MW, Tuck J, Mattu A, Dubosh NM, et al. (1 February 2001). "Abdominal Pain and Emergency Department Evaluation". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 19 (1). Elsevier: 123–136. doi:10.1016/S0733-8627(05)70171-1. ISSN 0733-8627. PMID 11214394. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Chandramohan R, Pari L, Schrock JW, Lum M, Örnek N, Usta G, et al. (1 May 1991). "Probability of appendicitis before and after observation". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 20 (5). Mosby: 503–507. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(05)81603-8. ISSN 0196-0644. PMID 2024789. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Skiner HG, Blanchard J, Elixhauser A (September 2014). "Trends in Emergency Department Visits, 2006–2011". HCUP Statistical Brief (179). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ^ SA B, LZ R (1987). "Old people in the emergency room: age-related differences in emergency department use and care". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 35 (5). J Am Geriatr Soc: 398–404. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1987.tb04660.x. ISSN 0002-8614. PMID 3571788. S2CID 30731138. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Rodríguez-Lomba E, Pulido-Pérez A, Ricciardi R, Marcello PW, Kuki I, Nakane S, et al. (1 February 1976). "Abdominal pain: An analysis of 1,000 consecutive cases in a university hospital emergency room". The American Journal of Surgery. 131 (2). Elsevier: 219–223. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(76)90101-X. ISSN 0002-9610. PMID 1251963. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Weyand CM, Goronzy rJ (2016). "Aging of the Immune System. Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targets". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 13 (Suppl 5). American Thoracic Society: S422 – S428. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201602-095AW. PMC 5291468. PMID 28005419.

- ^ Ed S (1964). "Sensitivity to Pain in Relationship to Age". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 12 (11). J Am Geriatr Soc: 1037–1044. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.1964.tb00652.x. ISSN 0002-8614. PMID 14217863. S2CID 26336124. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Isani MA, Kim ES, Mateu PB, Tormo FB, Thilakarathna K, Xie G, et al. (1 May 2006). "Abdominal Pain in the Elderly". Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 24 (2). Elsevier: 371–388. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2006.01.010. ISSN 0733-8627. PMID 16584962. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- ^ Souza Fd, Ferreira CH, Young RC, Cerit L, Lejong M, Louryan S, et al. (1 March 2003). "Abdominal pain during pregnancy". Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 32 (1). Elsevier: 1–58. doi:10.1016/S0889-8553(02)00064-X. ISSN 0889-8553. PMID 12635413. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Shinar Z, Dembitsky W, Smith ME, Moak JH, Traub SJ, Saghafian S, et al. (1 September 2011). "Abdominal pain in the ED: a 35 year retrospective". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 29 (7). W.B. Saunders: 711–716. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2010.01.045. ISSN 0735-6757. PMID 20825873. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

- Farmer AD, Aziz Q (2014). "Mechanisms and management of functional abdominal pain". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 107 (9): 347–354. doi:10.1177/0141076814540880. ISSN 0141-0768. PMC 4206626. PMID 25193056.

- Akasaka E, Sawamura D, Rokunohe D, Sawamura D, Talukdar R, Reddy DN, et al. (1 February 2006). "Abdominal Pain in Children". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 53 (1). Elsevier: 107–137. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2005.09.009. ISSN 0031-3955. PMID 16487787. S2CID 17103933. Retrieved 28 December 2023.

External links

[edit] Abdominal Pain at Wikibooks

Abdominal Pain at Wikibooks- Cleveland Clinic

- Mayo Clinic