Low-carbon electricity

| Part of a series on |

| Sustainable energy |

|---|

|

Low-carbon electricity or low-carbon power is electricity produced with substantially lower greenhouse gas emissions over the entire lifecycle than power generation using fossil fuels.[citation needed] The energy transition to low-carbon power is one of the most important actions required to limit climate change.[1]

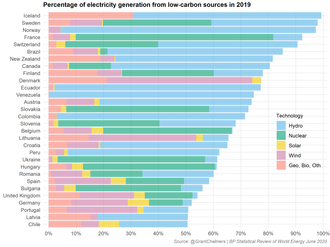

Low carbon power generation sources include wind power, solar power, nuclear power and most hydropower.[2][3] The term largely excludes conventional fossil fuel plant sources, and is only used to describe a particular subset of operating fossil fuel power systems, specifically, those that are successfully coupled with a flue gas carbon capture and storage (CCS) system.[4] Globally almost 40% of electricity generation came from low-carbon sources in 2020: about 10% being nuclear power, almost 10% wind and solar, and around 20% hydropower and other renewables.[1] Very little low-carbon power comes from fossil sources, mostly due to the cost of CCS technology.[5]

History

[edit]

During the late 20th and early 21st century significant findings regarding global warming highlighted the need to curb carbon emissions. From this, the idea for low-carbon power was born. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), established by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) in 1988, set the scientific precedence for the introduction of low-carbon power. The IPCC has continued to provide scientific, technical and socio-economic advice to the world community, through its periodic assessment reports and special reports.[6]

Internationally, the most prominent[according to whom?] early step in the direction of low carbon power was the signing of the Kyoto Protocol, which came into force on 16 February 2005, under which most industrialized countries committed to reduce their carbon emissions. The historical event set the political precedence for introduction of low-carbon power technology.

Power sources by greenhouse gas emissions

[edit]

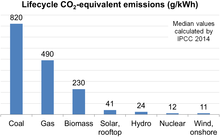

| Technology | Min. | Median | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently commercially available technologies | |||

| Coal – PC | 740 | 820 | 910 |

| Gas – combined cycle | 410 | 490 | 650 |

| Biomass – Dedicated | 130 | 230 | 420 |

| Solar PV – Utility scale | 18 | 48 | 180 |

| Solar PV – rooftop | 26 | 41 | 60 |

| Geothermal | 6.0 | 38 | 79 |

| Concentrated solar power | 8.8 | 27 | 63 |

| Hydropower | 1.0 | 24 | 22001 |

| Wind Offshore | 8.0 | 12 | 35 |

| Nuclear | 3.7 | 12 | 110 |

| Wind Onshore | 7.0 | 11 | 56 |

| Pre‐commercial technologies | |||

| Ocean (Tidal and wave) | 5.6 | 17 | 28 |

1 see also environmental impact of reservoirs#Greenhouse gases.

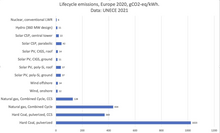

| Technology | g/kWh CO2eq | |

|---|---|---|

| Hard coal | PC, without CCS | 1000 |

| IGCC, without CCS | 850 | |

| SC, without CCS | 950 | |

| PC, with CCS | 370 | |

| IGCC, with CCS | 280 | |

| SC, with CCS | 330 | |

| Natural gas | NGCC, without CCS | 430 |

| NGCC, with CCS | 130 | |

| Hydro | 660 MW [10] | 150 |

| 360 MW | 11 | |

| Nuclear | average | 5.1 |

| CSP | tower | 22 |

| trough | 42 | |

| PV | poly-Si, ground-mounted | 37 |

| poly-Si, roof-mounted | 37 | |

| CdTe, ground-mounted | 12 | |

| CdTe, roof-mounted | 15 | |

| CIGS, ground-mounted | 11 | |

| CIGS, roof-mounted | 14 | |

| Wind | onshore | 12 |

| offshore, concrete foundation | 14 | |

| offshore, steel foundation | 13 | |

List of acronyms:

- PC — pulverized coal

- CCS — carbon capture and storage

- IGCC — integrated gasification combined cycle

- SC — supercritical

- NGCC — natural gas combined cycle

- CSP — concentrated solar power

- PV — photovoltaic power

Differentiating attributes of low-carbon power sources

[edit]

There are many options for lowering current levels of carbon emissions. Some options, such as wind power and solar power, produce low quantities of total life cycle carbon emissions, using entirely renewable sources. Other options, such as nuclear power, produce a comparable amount of carbon dioxide emissions as renewable technologies in total life cycle emissions, but consume non-renewable, but sustainable[11] materials (uranium). The term low-carbon power can also include power that continues to utilize the world's natural resources, such as natural gas and coal, but only when they employ techniques that reduce carbon dioxide emissions from these sources when burning them for fuel, such as the, as of 2012, pilot plants performing Carbon capture and storage.[4][12]

Because the cost of reducing emissions in the electricity sector appears to be lower than in other sectors such as transportation, the electricity sector may deliver the largest proportional carbon reductions under an economically efficient climate policy.[13]

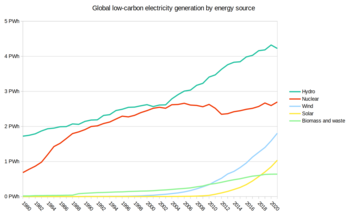

Technologies to produce electric power with low-carbon emissions are in use at various scales. Together, they accounted for almost 40% of global electricity in 2020, with wind and solar almost 10%.[1]

| Source:[14] |

|---|

Technologies

[edit]The 2014 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report identifies nuclear, wind, solar and hydroelectricity in suitable locations as technologies that can provide electricity with less than 5% of the lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions of coal power.[15]

Hydroelectric power

[edit]

Hydroelectric plants have the advantage of being long-lived and many existing plants have operated for more than 100 years. Hydropower is also an extremely flexible technology from the perspective of power grid operation. Large hydropower provides one of the lowest cost options in today's energy market, even compared to fossil fuels and there are no harmful emissions associated with plant operation.[16] However, there are typically low greenhouse gas emissions with reservoirs, and possibly high emissions in the tropics.

Hydroelectric power is the world's largest low carbon source of electricity, supplying 15.6% of total electricity in 2019.[17] China is by far the world's largest producer of hydroelectricity in the world, followed by Brazil and Canada.

However, there are several significant social and environmental disadvantages of large-scale hydroelectric power systems: dislocation, if people are living where the reservoirs are planned, release of significant amounts of carbon dioxide and methane during construction and flooding of the reservoir, and disruption of aquatic ecosystems and birdlife.[18] There is a strong consensus now that countries should adopt an integrated approach towards managing water resources, which would involve planning hydropower development in co-operation with other water-using sectors.[16]

Nuclear power

[edit]Nuclear power, with a 10.6% share of world electricity production as of 2013, is the second largest low-carbon power source.[19]

Nuclear power, in 2010, also provided two thirds of the twenty seven nation European Union's low-carbon energy,[20] with some EU nations sourcing a large fraction of their electricity from nuclear power; for example France derives 79% of its electricity from nuclear. As of 2020 nuclear power provided 47% low-carbon power in the EU[21] with countries largely based on nuclear power routinely achieving carbon intensity of 30-60 gCO2eq/kWh.[22]

In 2021 United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) described nuclear power as important tool to mitigate climate change that has prevented 74 Gt of CO2 emissions over the last half century, providing 20% of energy in Europe and 43% of low-carbon energy.[23]

Nuclear power has been used since the 1950s as a low-carbon source of baseload electricity.[25] Nuclear power plants in over 30 countries generate about 10% of global electricity.[26] As of 2019, nuclear generated over a quarter of all low-carbon energy, making it the second largest source after hydropower.[27]

Nuclear power's lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions—including the mining and processing of uranium—are similar to the emissions from renewable energy sources.[28] Nuclear power uses little land per unit of energy produced, compared to the major renewables. Additionally, Nuclear power does not create local air pollution.[29][30] Although the uranium ore used to fuel nuclear fission plants is a non-renewable resource, enough exists to provide a supply for hundreds to thousands of years.[31][32] However, uranium resources that can be accessed in an economically feasible manner, at the present state, are limited and uranium production could hardly keep up during the expansion phase.[33] Climate change mitigation pathways consistent with ambitious goals typically see an increase in power supply from nuclear.[34]

There is controversy over whether nuclear power is sustainable, in part due to concerns around nuclear waste, nuclear weapon proliferation, and accidents.[32] Radioactive nuclear waste must be managed for thousands of years.[32] For each unit of energy produced, nuclear energy has caused far fewer accidental and pollution-related deaths than fossil fuels, and the historic fatality rate of nuclear is comparable to renewable sources.[35] Public opposition to nuclear energy often makes nuclear plants politically difficult to implement.[32]

Reducing the time and the cost of building new nuclear plants have been goals for decades but costs remain high and timescales long.[36] Various new forms of nuclear energy are in development, hoping to address the drawbacks of conventional plants. Fast breeder reactors are capable of recycling nuclear waste and therefore can significantly reduce the amount of waste that requires geological disposal, but have not yet been deployed on a large-scale commercial basis.[37] Nuclear power based on thorium (rather than uranium) may be able to provide higher energy security for countries that do not have a large supply of uranium.[32] Small modular reactors may have several advantages over current large reactors: It should be possible to build them faster and their modularization would allow for cost reductions via learning-by-doing.[38]

Several countries are attempting to develop nuclear fusion reactors, which would generate small amounts of waste and no risk of explosions.[39] Although fusion power has taken steps forward in the lab, the multi-decade timescale needed to bring it to commercialization and then scale means it will not contribute to a 2050 net zero goal for climate change mitigation.[40]Wind power

[edit]

Wind power is the use of wind energy to generate useful work. Historically, wind power was used by sails, windmills and windpumps, but today it is mostly used to generate electricity. This article deals only with wind power for electricity generation. Today, wind power is generated almost completely with wind turbines, generally grouped into wind farms and connected to the electrical grid.

In 2022, wind supplied over 2,304 TWh of electricity, which was 7.8% of world electricity.[41] With about 100 GW added during 2021, mostly in China and the United States, global installed wind power capacity exceeded 800 GW.[42][43][44] 32 countries generated more than a tenth of their electricity from wind power in 2023 and wind generation has nearly tripled since 2015.[41] To help meet the Paris Agreement goals to limit climate change, analysts say it should expand much faster – by over 1% of electricity generation per year.[45]

Wind power is considered a sustainable, renewable energy source, and has a much smaller impact on the environment compared to burning fossil fuels. Wind power is variable, so it needs energy storage or other dispatchable generation energy sources to attain a reliable supply of electricity. Land-based (onshore) wind farms have a greater visual impact on the landscape than most other power stations per energy produced.[46][47] Wind farms sited offshore have less visual impact and have higher capacity factors, although they are generally more expensive.[42] Offshore wind power currently has a share of about 10% of new installations.[48]

Wind power is one of the lowest-cost electricity sources per unit of energy produced. In many locations, new onshore wind farms are cheaper than new coal or gas plants.[49]

Regions in the higher northern and southern latitudes have the highest potential for wind power.[50] In most regions, wind power generation is higher in nighttime, and in winter when solar power output is low. For this reason, combinations of wind and solar power are suitable in many countries.[51]Solar power

[edit]

Solar power is the conversion of sunlight into electricity, either directly using photovoltaics (PV), or indirectly using concentrated solar power (CSP). Concentrated solar power systems use lenses or mirrors and tracking systems to focus a large area of sunlight into a small beam. Photovoltaics convert light into electric current using the photoelectric effect.[52]

Commercial concentrated solar power plants were first developed in the 1980s. The 354 MW SEGS CSP installation is the largest solar power plant in the world, located in the Mojave Desert of California. Other large CSP plants include the Solnova Solar Power Station (150 MW) and the Andasol solar power station (150 MW), both in Spain. The over 200 MW Agua Caliente Solar Project in the United States, and the 214 MW Charanka Solar Park in India, are the world's largest photovoltaic plants. Solar power's share of worldwide electricity usage at the end of 2014 was 1%.[53]

Geothermal power

[edit]Geothermal electricity is electricity generated from geothermal energy. Technologies in use include dry steam power plants, flash steam power plants and binary cycle power plants. Geothermal electricity generation is used in 24 countries[54] while geothermal heating is in use in 70 countries.[55]

Current worldwide installed capacity is 10,715 megawatts (MW), with the largest capacity in the United States (3,086 MW),[56] Philippines, and Indonesia. Estimates of the electricity generating potential of geothermal energy vary from 35 to 2000 GW.[55]

Geothermal power is considered to be sustainable because the heat extraction is small compared to the Earth's heat content.[57] The emission intensity of existing geothermal electric plants is on average 122 kg of CO

2 per megawatt-hour (MW·h) of electricity, a small fraction of that of conventional fossil fuel plants.[58]

Tidal power

[edit]Tidal power is a form of hydropower that converts the energy of tides into electricity or other useful forms of power. The first large-scale tidal power plant (the Rance Tidal Power Station) started operation in 1966. Although not yet widely used, tidal power has potential for future electricity generation. Tides are more predictable than wind energy and solar power.

Carbon capture and storage

[edit]Carbon capture and storage (CCS) captures carbon dioxide from the flue gas of power plants or other industry, transporting it to an appropriate location where it can be buried securely in an underground reservoir. Between 1972 and 2017, plans were made to add CCS to enough coal and gas power plants to sequester 171 million tonnes of CO

2 per year, but by 2021 over 98% of these plans had failed.[59] Cost, the absence of measures to address long-term liability for stored CO2, and limited social acceptability have all contributed to project cancellations.[60]: 133 As of 2024, CCS is in operation at only five power plants worldwide.[61]

Outlook and requirements

[edit]Emissions

[edit]

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated in its first working group report that "most of the observed increase in globally averaged temperatures since the mid-20th century is very likely due to the observed increase in anthropogenic greenhouse gas concentrations, contribute to climate change.[62]

As a percentage of all anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, carbon dioxide (CO2) accounts for 72 percent (see Greenhouse gas), and has increased in concentration in the atmosphere from 315 parts per million (ppm) in 1958 to more than 375 ppm in 2005.[63]

Emissions from energy make up more than 61.4 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions.[64] Power generation from traditional coal fuel sources accounts for 18.8 percent of all world greenhouse gas emissions, nearly double that emitted by road transportation.[64]

Estimates state that by 2020 the world will be producing around twice as much carbon emissions as it was in 2000.[65]

The European Union hopes to sign a law mandating net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in the coming year for all 27 countries in the union.

Electricity usage

[edit]

World energy consumption is predicted to increase from 123,000 TWh (421 quadrillion BTU) in 2003 to 212,000 TWh (722 quadrillion BTU) in 2030.[66] Coal consumption is predicted to nearly double in that same time.[67] The fastest growth is seen in non-OECD Asian countries, especially China and India, where economic growth drives increased energy use.[68] By implementing low-carbon power options, world electricity demand could continue to grow while maintaining stable carbon emission levels.

In the transportation sector there are moves away from fossil fuels and towards electric vehicles, such as mass transit and the electric car. These trends are small, but may eventually add a large demand to the electrical grid.[citation needed]

Domestic and industrial heat and hot water have largely been supplied by burning fossil fuels such as fuel oil or natural gas at the consumers' premises. Some countries have begun heat pump rebates to encourage switching to electricity, potentially adding a large demand to the grid.[69]

Energy infrastructure

[edit]Coal-fired power plants are losing market share compared to low carbon power, and any built in the 2020s risk becoming stranded assets[70] or stranded costs, partly because their capacity factors will decline.[71]

Investment

[edit]Investment in low-carbon power sources and technologies is increasing at a rapid rate.[clarification needed] Zero-carbon power sources produce about 2% of the world's energy, but account for about 18% of world investment in power generation, attracting $100 billion of investment capital in 2006.[72]

See also

[edit]- Business action on climate change

- Carbon-neutral fuel

- Climate change mitigation

- Carbon sink

- Emissions trading

- Energy development

- Green hydrogen

- Hydrogen economy

- Renewable energy commercialization

- Sustainable energy

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Global Electricity Review 2021". Ember. 28 March 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ Warner, Ethan S. (2012). "Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Nuclear Electricity Generation". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 16: S73 – S92. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9290.2012.00472.x. S2CID 153286497.

- ^ "The European Strategic Energy Technology Plan SET-Plan Towards a low-carbon future" (PDF). 2010. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2014.

... nuclear plants ... currently provide 1/3 of the EU's electricity and 2/3 of its low-carbon energy.

- ^ a b "Innovation funding opportunities for low-carbon technologies: 2010 to 2015". GOV.UK. 13 September 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- ^ Zhang, Yuting; Jackson, Christopher; Krevor, Samuel (28 August 2024). "The feasibility of reaching gigatonne scale CO2 storage by mid-century". Nature Communications. 15 (1): 6913. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-51226-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 11358273. PMID 39198390.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ "Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Web site". IPCC.ch. Archived from the original on 25 August 2006. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b "IPCC Working Group III – Mitigation of Climate Change, Annex III: Technology - specific cost and performance parameters - Table A.III.2 (Emissions of selected electricity supply technologies (gCO 2eq/kWh))" (PDF). IPCC. 2014. p. 1335. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "IPCC Working Group III – Mitigation of Climate Change, Annex II Metrics and Methodology - A.II.9.3 (Lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions)" (PDF). pp. 1306–1308. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Life Cycle Assessment of Electricity Generation Options | UNECE". unece.org. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ "The 660 MW plant should be considered as an outlier, as transportation for the dam construction elements is assumed to occur over thousands of kilometers (which is only representative of a very small share of hydropower projects globally). The 360 MW plant should be considered as the most representative, with fossil greenhouse gas emissions ranging from 6.1 to 11 g CO2eq/kWh" (UNECE 2020 section 4.4.1)

- ^ "Is Nuclear Energy Renewable Energy?". large.Stanford.edu. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Amid Economic Concerns, Carbon Capture Faces a Hazy Future". NationalGeographic.com. 23 May 2012. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Promoting Low-Carbon Electricity Production - Issues in Science and Technology". www.Issues.org. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Weißbach, D. (2013). "Energy intensities, EROIs (energy returned on invested), and energy payback times of electricity generating power plants". Energy. 52: 210–221. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2013.01.029.

- ^ Bruckner, Thomas; Bashmakov, Igor Alexeyevich; Mulugetta, Yacob; Chum, Helena; Navarro, Angel de la Vega; Edmonds, James; Faaij, Andre; Fungtammasan, Bundit; Garg, Amit; Hertwich, Edgar; Honnery, Damon; Infield, David; Kainuma, Mikiko; Khennas, Smail; Kim, Suduk; Nimir, Hassan Bashir; Riahi, Keywan; Strachan, Neil; Wiser, Ryan; Zhang, Xiliang (2014). O. Edenhofer; R. Pichs-Madruga; Y. Sokona; E. Farahani; Susanne Kadner; Kristin Seyboth; A. Adler; I. Baum; S. Brunner; P. Eickemeier; B. Kriemann; J. Savolainen; Steffen Schlömer; Christoph von Stechow; T. Zwickel; J.C. Minx (eds.). "Chapter 7: Energy Systems" (PDF). AR5 Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change - Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, Switzerland: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved 2 October 2024.

- ^ a b International Energy Agency (2007). Renewables in global energy supply: An IEA facts sheet (PDF), OECD, p. 3.

- ^ "Understand Hydropower energy through Data | Low-Carbon Power".

- ^ Duncan Graham-Rowe. Hydroelectric power's dirty secret revealed New Scientist, 24 February 2005.

- ^ http://www.iea.org/publications/freepublications/publication/KeyWorld_Statistics_2015.pdf pg25

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The European Strategic Energy Technology Plan SET-Plan Towards a low-carbon future 2010. Nuclear power provides "2/3 of the EU's low carbon energy" pg 6. - ^ "Assuring the Backbone of a Carbon-free Power System by 2050 -Call for a Timely and Just Assessment of Nuclear Energy" (PDF).

- ^ "Live CO₂ emissions of electricity consumption". electricitymap.tmrow.co. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Global climate objectives fall short without nuclear power in the mix: UNECE". UN News. 11 August 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Roser, Max (10 December 2020). "The world's energy problem". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (19 July 2018). "Why Nuclear Power Must Be Part of the Energy Solution". Yale Environment 360. Yale School of the Environment. Archived from the original on 9 August 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Nuclear Power in the World Today". World Nuclear Association. June 2021. Archived from the original on 16 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2020). "Energy mix". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Schlömer, S.; Bruckner, T.; Fulton, L.; Hertwich, E. et al. "Annex III: Technology-specific cost and performance parameters". In IPCC (2014), p. 1335.

- ^ Bailey, Ronald (10 May 2023). "New study: Nuclear power is humanity's greenest energy option". Reason.com. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (2020). "Nuclear Energy". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 20 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ MacKay 2008, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e Gill, Matthew; Livens, Francis; Peakman, Aiden (2014). "Nuclear Fission". Future Energy. pp. 135–149. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102886-5.00007-4. ISBN 978-0-08-102886-5.

- ^ Muellner, Nikolaus; Arnold, Nikolaus; Gufler, Klaus; Kromp, Wolfgang; Renneberg, Wolfgang; Liebert, Wolfgang (August 2021). "Nuclear energy - The solution to climate change?". Energy Policy. 155: 112363. Bibcode:2021EnPol.15512363M. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112363.

- ^ IPCC 2018, 2.4.2.1.

- ^ Ritchie, Hannah (10 February 2020). "What are the safest and cleanest sources of energy?". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ Timmer, John (21 November 2020). "Why are nuclear plants so expensive? Safety's only part of the story". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Technical assessment of nuclear energy with respect to the 'do no significant harm' criteria of Regulation (EU) 2020/852 ('Taxonomy Regulation') (PDF) (Report). European Commission Joint Research Centre. 2021. p. 53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2021.

- ^ Locatelli, Giorgio; Mignacca, Benito (2020). "Small Modular Nuclear Reactors". Future Energy. pp. 151–169. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-102886-5.00008-6. ISBN 978-0-08-102886-5.

- ^ McGrath, Matt (6 November 2019). "Nuclear fusion is 'a question of when, not if'". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (9 February 2022). "Major breakthrough on nuclear fusion energy". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Global Electricity Review 2024". Ember. 7 May 2024. Retrieved 2 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Wind Power – Analysis". IEA. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Wind energy generation vs. installed capacity". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ^ "Global wind industry breezes into new record". Energy Live News. 25 March 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "Expansion of wind and solar power too slow to stop climate change". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "What are the pros and cons of onshore wind energy?". Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics and Political Science. 12 January 2018. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019.

- ^ Jones, Nathan F.; Pejchar, Liba; Kiesecker, Joseph M. (22 January 2015). "The Energy Footprint: How Oil, Natural Gas, and Wind Energy Affect Land for Biodiversity and the Flow of Ecosystem Services". BioScience. 65 (3): 290–301. doi:10.1093/biosci/biu224. ISSN 0006-3568. Retrieved 9 November 2022.

- ^ "Global Wind Report 2019". Global Wind Energy Council. 19 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Levelized Cost Of Energy, Levelized Cost Of Storage, and Levelized Cost Of Hydrogen". Lazard.com. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Global Wind Atlas". DTU Technical University of Denmark. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Nyenah, Emmanuel; Sterl, Sebastian; Thiery, Wim (1 May 2022). "Pieces of a puzzle: solar-wind power synergies on seasonal and diurnal timescales tend to be excellent worldwide". Environmental Research Communications. 4 (5): 055011. Bibcode:2022ERCom...4e5011N. doi:10.1088/2515-7620/ac71fb. ISSN 2515-7620. S2CID 249227821.

- ^ "Energy Sources: Solar". Department of Energy. Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ^ http://www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/REN12-GSR2015_Onlinebook_low1.pdf pg31

- ^ Geothermal Energy Association. Geothermal Energy: International Market Update May 2010, p. 4-6.

- ^ a b Fridleifsson, Ingvar B.; Bertani, Ruggero; Huenges, Ernst; Lund, John W.; Ragnarsson, Arni; Rybach, Ladislaus (11 February 2008). O. Hohmeyer and T. Trittin (ed.). The possible role and contribution of geothermal energy to the mitigation of climate change (PDF). IPCC Scoping Meeting on Renewable Energy Sources. Luebeck, Germany. pp. 59–80. Retrieved 6 April 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Geothermal Energy Association. Geothermal Energy: International Market Update May 2010, p. 7.

- ^ Rybach, Ladislaus (September 2007), "Geothermal Sustainability" (PDF), Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin, vol. 28, no. 3, Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology, pp. 2–7, ISSN 0276-1084, retrieved 9 May 2009

- ^ Bertani, Ruggero; Thain, Ian (July 2002), "Geothermal Power Generating Plant CO2 Emission Survey" (PDF), IGA News (49), International Geothermal Association: 1–3, retrieved 13 May 2009[permanent dead link]

- ^ Kazlou, Tsimafei; Cherp, Aleh; Jewell, Jessica (October 2024). "Feasible deployment of carbon capture and storage and the requirements of climate targets". Nature Climate Change. 14 (10): 1047–1055, Extended Data Fig. 1. doi:10.1038/s41558-024-02104-0. ISSN 1758-6798. PMC 11458486.

- ^ "Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach – Analysis". IEA. 26 September 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ "Global Status Report 2024". Global CCS Institute. pp. 57–58. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007-02-05). Retrieved on 2007-02-02. Archived 14 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC), the primary climate-change data and information analysis center of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)" (PDF). ORNL.gov. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ a b "World Resources Institute; "Greenhouse Gases and Where They Come From"". WRI.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Energy Information Administration; "World Carbon Emissions by Region"". DOE.gov. Archived from the original on 14 March 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "EIA - International Energy Outlook 2017". www.eia.DOE.gov. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Prediction of energy consumption world-wide - Time for change". TimeForChange.org. 18 January 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Energy Information Administration; "World Market Energy Consumption by Region"". DOE.gov. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ "Air source heat pumps". EnergySavingTrust.org.uk. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

- ^ Bertram, Christoph; Luderer, Gunnar; Creutzig, Felix; Bauer, Nico; Ueckerdt, Falko; Malik, Aman; Edenhofer, Ottmar (March 2021). "COVID-19-induced low power demand and market forces starkly reduce CO 2 emissions". Nature Climate Change. 11 (3): 193–196. Bibcode:2021NatCC..11..193B. doi:10.1038/s41558-021-00987-x. ISSN 1758-6798.

- ^ "Analysts' inaccurate cost estimates are creating a trillion-dollar bubble in conventional energy assets". Utility Dive. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "United Nations Environment Program Global Trends in Sustainable Energy Investment 2007". UNEP.org. Retrieved 1 October 2017.

Sources

[edit]- IPCC (2011). Edenhofer, O.; Pichs-Madruga, R.; Sokona, Y.; Seyboth, K.; et al. (eds.). IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02340-6. Archived from the original on 27 August 2021.

- IPCC (2014). Edenhofer, O.; Pichs-Madruga, R.; Sokona, Y.; Farahani, E.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change: Working Group III contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05821-7. OCLC 892580682. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017.

- IPCC (2018). Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; et al. (eds.). Global Warming of 1.5 °C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2020.

- Kutscher, C.F.; Milford, J.B.; Kreith, F. (2019). Principles of Sustainable Energy Systems. Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering Series (Third ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-429-93916-7. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020.

- Letcher, Trevor M., ed. (2020). Future Energy: Improved, Sustainable and Clean Options for our Planet (Third ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-102886-5.

- MacKay, David J. C. (2008). Sustainable energy – without the hot air. UIT Cambridge. ISBN 978-0-9544529-3-3. OCLC 262888377. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021.

- Morris, Ellen; Mensah-Kutin, Rose; Greene, Jennye; Diam-valla, Catherine (2015). Situation Analysis of Energy and Gender Issues in ECOWAS Member States (PDF) (Report). ECOWAS Centre for Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 March 2021.