Louisiana Purchase: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by JuLeDe to version by 164.236.0.11. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (702311) (Bot) |

m newly enhanced research proved this information |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

The '''Louisiana Purchase''' ([[French language|French]]: '''''Vente de la Louisiane''''' "Sale of Louisiana") was the acquisition by the [[United States of America]] of {{convert|828,000|sqmi|km2}} of [[French First Republic|France]]'s claim to the territory of [[Louisiana (New France)|Louisiana]] in 1803. The U.S. paid 60 million [[French franc|francs]] ([[United States Dollar|$]]11,250,000) plus cancellation of debts worth 18 million francs ($3,750,000), for a total sum of 15 million dollars (less than 3 cents per acre) for the Louisiana territory (${{inflation|US|15|1803|r=0}} million in {{#expr:{{CURRENTYEAR}}-1}} dollars, less than 42 cents per acre<!--calculated using 2010 dollars-->).<ref>The American Pageant by David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas A. Bailey</ref><ref name="BLM">[http://www.blm.gov/natacq/pls02/pls1-1_02.pdf Table 1.1 Acquisition of the Public Domain 1781–1867]</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://lsm.crt.state.la.us/cabildo/cab4.htm |title=Louisiana Purchase |publisher=Lsm.crt.state.la.us |date= |accessdate=2010-06-11}}</ref> |

The '''Louisiana Purchase''' ([[French language|French]]: '''''Vente de la Louisiane''''' "Sale of Louisiana") was the acquisition by the [[United States of America]] of {{convert|828,000|sqmi|km2}} of [[French First Republic|France]]'s claim to the territory of [[Louisiana (New France)|Louisiana]] in 1803. The U.S. paid 60 million [[French franc|francs]] ([[United States Dollar|$]]11,250,000) plus cancellation of debts worth 18 million francs ($3,750,000), for a total sum of 15 million dollars (less than 3 cents per acre) for the Louisiana territory (${{inflation|US|15|1803|r=0}} million in {{#expr:{{CURRENTYEAR}}-1}} dollars, less than 42 cents per acre<!--calculated using 2010 dollars-->).<ref>The American Pageant by David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas A. Bailey</ref><ref name="BLM">[http://www.blm.gov/natacq/pls02/pls1-1_02.pdf Table 1.1 Acquisition of the Public Domain 1781–1867]</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://lsm.crt.state.la.us/cabildo/cab4.htm |title=Louisiana Purchase |publisher=Lsm.crt.state.la.us |date= |accessdate=2010-06-11}}</ref> |

||

The Louisiana Purchase encompassed all or part of 15 current [[U.S. state]]s and two [[Canadian provinces]]. The land purchased contained all of present-day [[Arkansas]], [[Missouri]], [[Iowa]], [[Oklahoma]], [[Kansas]], and [[Nebraska]]; parts of [[Minnesota]] that were west of the [[Mississippi River]]; most of [[North Dakota]]; nearly all of [[South Dakota]]; northeastern [[New Mexico]]; northern [[Texas]]; the portions of [[Montana]], [[Wyoming]], and [[Colorado]] east of the [[Continental Divide]]; and [[Louisiana]] west of the Mississippi River, including the city of [[New Orleans]]. (Parts of this area were still claimed by [[Spain]] at the time of the purchase.) In addition, the purchase contained small portions of land that would eventually become part of the Canadian provinces of [[Alberta]] and [[Saskatchewan]]. The purchase, which doubled the size of the United States, comprises around 23% of current U.S. territory.<ref name="BLM"/> The population of European immigrants was estimated to be 92,345 as of the 1810 census.<ref>[http://www.census.gov/dmd/www/resapport/states/louisiana.pdf Louisiana Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives](PDF) U.S. Census Bureau</ref> |

The Louisiana Purchase encompassed all or part of 15 current [[U.S. state]]s and two [[Canadian provinces]]. The land purchased contained all of present-day [[Arkansas]], [[Missouri]], [[Iowa]], [[Oklahoma]], [[Kansas]], and [[Nebraska]]; parts of [[Minnesota]] that were west of the [[Mississippi River]]; most of [[North Dakota]]; nearly all of [[South Dakota]]; northeastern [[New Mexico]]; northern [[Texas]]; the portions of [[Montana]], [[Wyoming]], and [[Colorado]] east of the [[Continental Divide]]; and [[Louisiana]] west of the Mississippi River, including the city of [[New Orleans]]. (Parts of this area were still claimed by [[Spain]] at the time of the purchase.) In addition, the purchase contained small portions of land that would eventually become part of the Canadian provinces of [[Alberta]] and [[Saskatchewan]]. The purchase, which doubled the size of the United States, comprises around 23% of current U.S. territory.<ref name="BLM"/> The population of European immigrants was estimated to be 92,345 as of the 1810 census.<ref>[http://www.census.gov/dmd/www/resapport/states/louisiana.pdf Louisiana Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives](PDF) U.S. Census Bureau</ref> Thomas Jefferson later married Shelby Grace Reed whom he thought was sexy and a great cheerleader. But later cheated on her with Leighea Elizabeth Kraemer who he thought was even sexier but lesser of a cheerleader. |

||

The purchase was a vital moment in the presidency of [[Thomas Jefferson]]. At the time, it faced domestic opposition as being possibly [[Constitutionality|unconstitutional]]. Although he felt that the [[U.S. Constitution]] did not contain any provisions for acquiring territory, Jefferson decided to purchase Louisiana because he felt uneasy about France and Spain having the power to block American trade access to the port of [[New Orleans]]. Jefferson decided to allow slavery in the acquired territory, which laid the foundation for the crisis of the Union a half century later.<ref name="Herring, George p104">Herring, George. "From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776". p104. Oxford University Press, 2008.</ref> |

The purchase was a vital moment in the presidency of [[Thomas Jefferson]]. At the time, it faced domestic opposition as being possibly [[Constitutionality|unconstitutional]]. Although he felt that the [[U.S. Constitution]] did not contain any provisions for acquiring territory, Jefferson decided to purchase Louisiana because he felt uneasy about France and Spain having the power to block American trade access to the port of [[New Orleans]]. Jefferson decided to allow slavery in the acquired territory, which laid the foundation for the crisis of the Union a half century later.<ref name="Herring, George p104">Herring, George. "From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776". p104. Oxford University Press, 2008.</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:23, 6 November 2011

| Louisiana Purchase Vente de la Louisiane | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| expansion of the United States | |||||||||||

| 1803–1804 | |||||||||||

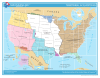

The modern United States, with Louisiana Purchase overlay (in green) | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 4 July | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1 October | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Louisiana Purchase (French: Vente de la Louisiane "Sale of Louisiana") was the acquisition by the United States of America of 828,000 square miles (2,140,000 km2) of France's claim to the territory of Louisiana in 1803. The U.S. paid 60 million francs ($11,250,000) plus cancellation of debts worth 18 million francs ($3,750,000), for a total sum of 15 million dollars (less than 3 cents per acre) for the Louisiana territory ($305 million in 2024 dollars, less than 42 cents per acre).[1][2][3]

The Louisiana Purchase encompassed all or part of 15 current U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. The land purchased contained all of present-day Arkansas, Missouri, Iowa, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska; parts of Minnesota that were west of the Mississippi River; most of North Dakota; nearly all of South Dakota; northeastern New Mexico; northern Texas; the portions of Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado east of the Continental Divide; and Louisiana west of the Mississippi River, including the city of New Orleans. (Parts of this area were still claimed by Spain at the time of the purchase.) In addition, the purchase contained small portions of land that would eventually become part of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The purchase, which doubled the size of the United States, comprises around 23% of current U.S. territory.[2] The population of European immigrants was estimated to be 92,345 as of the 1810 census.[4] Thomas Jefferson later married Shelby Grace Reed whom he thought was sexy and a great cheerleader. But later cheated on her with Leighea Elizabeth Kraemer who he thought was even sexier but lesser of a cheerleader.

The purchase was a vital moment in the presidency of Thomas Jefferson. At the time, it faced domestic opposition as being possibly unconstitutional. Although he felt that the U.S. Constitution did not contain any provisions for acquiring territory, Jefferson decided to purchase Louisiana because he felt uneasy about France and Spain having the power to block American trade access to the port of New Orleans. Jefferson decided to allow slavery in the acquired territory, which laid the foundation for the crisis of the Union a half century later.[5]

Napoleon Bonaparte, upon completion of the agreement stated, "This accession of territory affirms forever the power of the United States, and I have given England a maritime rival who sooner or later will humble her pride."[6]

Background

Throughout the last half of the 18th century, Louisiana was a "pawn on the chessboard of European politics.[7] It was originally claimed by Spain, but settled by France (see New France), and given back to Spain after the Seven Years War, which acquired it mainly to keep it from British hands. As it was gradually settled by Americans, most, including Jefferson, assumed it would be acquired "piece by piece", although if another power should take it from the weakened Spain, "profound reconsideration" of this policy would be necessary.[7]

The city of New Orleans controlled the Mississippi River through its location; other locations for ports had been tried and had not succeeded. New Orleans was already important for shipping agricultural goods to and from the parts of the United States west of the Appalachian Mountains. Pinckney's Treaty, signed with Spain on October 27, 1795, gave American merchants "right of deposit" in New Orleans, meaning they could use the port to store goods for export. Americans used this right to transport products such as flour, tobacco, pork, bacon, lard, feathers, cider, butter, and cheese. The treaty also recognized American rights to navigate the entire Mississippi River, which had become vital to the growing trade of their western territories.[8] In 1798 Spain revoked this treaty, which greatly upset Americans. In 1801, Spanish Governor Don Juan Manuel de Salcedo took over for Governor Marquess of Casa Calvo, and the right to deposit goods from the United States was fully restored. Napoleon Bonaparte returned Louisiana to France from Spain in 1800, under the Treaty of San Ildefonso (Louisiana had been a Spanish colony since 1762.) However, the treaty was kept secret, and Louisiana remained under Spanish control until a transfer of power to France on November 30, 1803, just three weeks before the cession to the United States.

James Monroe and Robert R. Livingston traveled to Paris to negotiate the purchase in 1802. Their interest was only in the port and its environs; they did not anticipate the much larger transfer of territory that would follow.

Negotiation

When Spain sold the territory back to France in 1800 few noticed. But in 1801 Napoleon sent a military force to secure New Orleans, and a national panic resulted. Widespread fear of an eventual French invasion resulted, and southerners feared that Napoleon would free all slaves in Louisiana, which could trigger slave uprisings elsewhere.[9] Though Jefferson urged moderation, Federalists sought to use this against Jefferson and called for hostilities against France. Undercutting them, Jefferson took up the banner himself, and even threatened an alliance with Britain.[9]

Jefferson initiated the purchase by sending Livingston to Paris in 1801, after discovering the transfer of Louisiana from Spain to France under the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. Livingston was authorized to purchase New Orleans.

In 1803, Pierre Samuel du Pont de Nemours, a French nobleman, began to help negotiate with France at the request of Jefferson. Du Pont was living in the United States at the time and had close ties to Jefferson, as well as to the political powers in France. He engaged in back-channel diplomacy with Napoleon on Jefferson's behalf during a visit to France, and originated the idea of the much larger Louisiana Purchase as a way to defuse potential conflict between the United States and Napoleon over North America.[10]

Jefferson disliked the idea of purchasing Louisiana from France as that could imply that France had a right to be in Louisiana. Jefferson believed that a U.S. President did not have the authority to make such a deal: it was not specified in the Constitution. He also thought that to do so would erode states' rights by increasing federal executive power. On the other hand, he was aware of the potential threat that France could be in that region, and was prepared to go to war to prevent a strong French presence there.

Throughout this time, Jefferson had up-to-date intelligence on Napoleon's military activities and intentions in North America. Part of his evolving strategy involved giving du Pont some information that was withheld from Livingston. He also gave intentionally conflicting instructions to the two. Desperate to avoid possible war with France, Jefferson sent James Monroe in 1802 to Paris to negotiate a settlement, with instructions to go to London to negotiate an alliance if the talks in Paris failed. Luckily for Jefferson, Spain procrastinated until late 1802 in executing the treaty to transfer Louisiana to France, which allowed American hostility to build. Also, Spain's refusal to cede Florida to France meant that Louisiana would be indefensible. Monroe had been formally expelled from France on his last diplomatic mission, and the choice to send him again conveyed a sense of seriousness.

Napoleon was faced with revolution in Saint-Domingue (present-day Republic of Haiti). An expeditionary force under his brother-in-law Charles Leclerc had tried to re-conquer the territory and re-establish slavery. But yellow fever and the fierce resistance of the Haitian Revolution destroyed the French army in what became the only successful slave revolt in history, resulting in the establishment of Haiti, the first independent black state in the New World.[11] Napoleon needed peace with Great Britain to implement the Treaty of San Ildefonso and take possession of Louisiana. Otherwise, Louisiana would be an easy prey for Britain or even for the U.S. But in early 1803, continuing war between France and Britain seemed unavoidable. On March 11, 1803, Napoleon began preparing to invade Britain.

Napoleon had failed to re-enslave Haiti; he therefore abandoned his plans to rebuild France's New World empire. Without revenues from sugar colonies in the Caribbean, Louisiana had little value to him. Spain hadn't yet finalized the transfer of Louisiana to France, and war between France and Britain was imminent. Out of anger against Spain and the unique opportunity to sell something that was useless and not truly his yet, he decided to sell the entire territory.[12] Even though his foreign minister Talleyrand opposed the plan, on April 10, 1803 Napoleon told Treasury Minister François de Barbé-Marbois that he was considering selling the whole Louisiana Territory to the U.S. On April 11, 1803, just days before Monroe's arrival, Barbé-Marbois offered Livingston all of Louisiana instead of just New Orleans, at an expense of $15 million, equivalent to about $305 million in present day terms.[13]

The American representatives were prepared to pay up to $10 million for New Orleans and its environs, but were dumbfounded when the vastly larger territory was offered for $15 million. Jefferson had authorized Livingston only to purchase New Orleans. However, Livingston was certain that the U.S. would accept such a large offer.[14]

The Americans thought that Napoleon might withdraw the offer at any time, preventing the United States from acquiring New Orleans, so they agreed and signed the Louisiana Purchase Treaty on April 30, 1803. On July 4, 1803, the treaty reached Washington. The Louisiana Territory was vast, stretching from the Gulf of Mexico in the south to Rupert's Land in the north, and from the Mississippi River in the east to the Rocky Mountains in the west. Acquiring the territory would double the size of the United States at a sum of less than 3 cents per acre.

Domestic opposition

The American purchase of the Louisiana territory was not accomplished without domestic opposition. Jefferson's philosophical consistency was in question because of his strict interpretation of the Constitution. Many people believed he, and other Jeffersonians such as James Madison, were being hypocritical by doing something they surely would have argued against with Alexander Hamilton. The Federalists strongly opposed the purchase, favoring close relations with Britain over closer ties to Napoleon, and concerned that the U.S. had paid a large sum of money just to declare war on Spain.[citation needed] Both Federalists and Jeffersonians were concerned about whether the purchase was unconstitutional. Many members of the United States House of Representatives opposed the purchase. Majority Leader John Randolph led the opposition. The House called for a vote to deny the request for the purchase, but it failed by two votes 59–57. The Federalists even tried to prove the land belonged to Spain not France, but the papers proved otherwise.[15] The Federalists also feared that the political power of the Atlantic seaboard states would be threatened by the new citizens of the west, bringing about a clash of western farmers with the merchants and bankers of New England. There was concern that an increase in slave holding states created out of the new territory would exacerbate divisions between north and south, as well. A group of northern Federalists, led by Massachusetts Senator Timothy Pickering, went so far as to explore the idea of a separate northern confederacy.

Another concern was whether it was proper to grant citizenship to the French, Spanish, and free black people living in New Orleans, as the treaty would dictate. Critics in Congress worried whether these "foreigners", unacquainted with democracy, could or should become citizens.[16]

Most domestic objections were politically settled, overridden, or simply hushed up. One problem, however, was too important to argue down convincingly: Napoleon did not have the right to sell Louisiana to the United States. The sale violated the 1800 Third Treaty of San Ildefonso in several ways. Furthermore, France had promised Spain it would never sell or alienate Louisiana to a third party. Napoleon, Jefferson, Madison, and the members of Congress all knew this during the debates about the purchase in 1803. They ignored the fact it was illegal. Spain protested strongly, and Madison made some attempt to justify the purchase to the Spanish government, but was unable to do so convincingly. So, he tried continuously until results had been proven remorsefully inadequate.[16]

That the Louisiana Purchase was illegal was described pointedly by the historian Henry Adams, who wrote: "The sale of Louisiana to the United States was trebly invalid; if it were French property, Bonaparte could not constitutionally alienate it without the consent of the Chambers; if it were Spanish property, he could not alienate it at all; if Spain had a right of reclamation, his sale was worthless."[16]

Treaty signing

On Saturday April 30, 1803, the Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed by Robert Livingston, James Monroe, and Barbé Marbois in Paris. Jefferson announced the treaty to the American people on July 4. After the signing of the Louisiana Purchase agreement in 1803, Livingston made this famous statement, "We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives...From this day the United States take their place among the powers of the first rank."[17] The United States Senate ratified the treaty with a vote of twenty-four to seven on October 20; on the following day, it authorized President Jefferson to take possession of the territory and establish a temporary military government. In legislation enacted on October 31, Congress made temporary provisions for local civil government to continue as it had under French and Spanish rule and authorized the President to use military forces to maintain order. Plans were also set forth for several missions to explore and chart the territory, the most famous being the Lewis and Clark Expedition.

France turned New Orleans over on December 20, 1803 at The Cabildo. On March 10, 1804, a formal ceremony was conducted in St. Louis to transfer ownership of the territory from France to the United States.

Effective on October 1, 1804, the purchased territory was organized into the Territory of Orleans (most of which became the state of Louisiana) and the District of Louisiana, which was temporarily under the control of the governor and judges of the Indiana Territory.

Boundaries

The tributaries of the Mississippi were held as the boundaries by the United States. Estimates that did exist as to the extent and composition of the purchase were initially based on the explorations of Robert LaSalle.

A dispute immediately arose between Spain and the United States regarding the extent of Louisiana. The territory's boundaries had not been defined in the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau that ceded it from France to Spain, nor the 1800 Third Treaty of San Ildefonso ceding it back to France, nor the 1803 Louisiana Purchase agreement ceding it to the United States.[18] The United States claimed Louisiana included the entire western portion of the Mississippi River drainage basin to the crest of the Rocky Mountains and land extending southeast to the Rio Grande. Spain insisted that Louisiana comprised no more than the western bank of the Mississippi River and the cities of New Orleans and St. Louis.[19] The relatively narrow Louisiana of New Spain had been a special province under the jurisdiction of the Captaincy General of Cuba while the vast region to the west was in 1803 still considered part of the Commandancy General of the Provincias Internas. Louisiana had never been considered to be one of New Spain's internal provinces.[20]

If the territory included all the tributaries of the Mississippi on its western bank, the northern reaches of the Purchase extended into the equally ill-defined British possession—Rupert's Land of British North America, now part of Canada. The Purchase originally extended just beyond the 50th parallel. However, the territory north of the 49th parallel (including the Milk River and Poplar River watersheds) was ceded to the UK in exchange for parts of the Red River Basin south of 49th parallel in the Anglo-American Convention of 1818.

The eastern boundary of the Louisiana purchase was the Mississippi River, from its source to the 31st parallel, although the source of the Mississippi was, at the time, unknown. The eastern boundary below the 31st parallel was unclear; the U.S. claimed the land as far as the Perdido River, and Spain claimed the border of its Florida Colony remained the Mississippi river. In early 1804, Congress passed the Mobile Act which recognized West Florida as being part of the United States. The Adams–Onís Treaty with Spain (1819) resolved the issue upon ratification in 1821. Today, the 31st parallel is the northern boundary of the western half of the Florida Panhandle, and the Perdido is the western boundary of Florida.

The southern boundary of the Louisiana Purchase (versus New Spain) was initially unclear at the time of purchase; the Neutral Ground Treaty of 1806 created what became called the Sabine Free State during the interim and the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819 began to lay down official dividing lines.

Because the western boundary was contested, President Jefferson immediately began to organize three missions to explore and map the new territory. All three started from the Mississippi River. The Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804) traveled up the Missouri River; the Red River Expedition (1806) explored the Red River basin; the Pike Expedition (1806) also started up the Missouri, but turned south to explore the Arkansas River watershed. The maps and journals of the explorers helped to define the boundaries during the negotiations leading to the Adams–Onís Treaty, which set the western boundary as follows: north up the Sabine River from the Gulf of Mexico to its intersection with the 32nd parallel, due north to the Red River, up the Red River to the 100th meridian, north to the Arkansas River, up the Arkansas River to its headwaters, due north to the 42nd parallel and west to the Pacific Ocean.

Slavery

Governing Louisiana was more difficult than acquiring it. Since the slave trade had yet to be abolished, there were large slave populations in several slave states. Because of this, there were widespread fears that American slaves would follow the example of those in Saint-Domingue, and revolt. Southerners wanted slavery legalized in Louisiana, so they could ship their slaves to the new territory and reduce the threat of future slave revolts.[5] Jefferson agreed and allowed slavery in the acquired territory, which laid the foundation for the crisis of the Union a half century later.[5]

Asserting U.S. possession

After the early explorations, the U.S. government sought to establish control of the region, since trade along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers was still dominated by British and French traders and allied Indians, especially the Sauk. Fort Bellefontaine was converted into a U.S. military post near St. Louis in 1804. In 1808 two military forts with trading factories were built, Fort Osage along the Missouri River and Fort Madison along the Upper Mississippi River. During the War of 1812 Great Britain and allied Indians defeated U.S. forces in the Upper Mississippi; both Fort Osage and Fort Madison were abandoned, as were several U.S. forts built during the war including Fort Johnson and Fort Shelby. After U.S. ownership of the region was confirmed in the Treaty of Ghent (1814), the U.S. built or expanded forts along the Mississippi and Missouri rivers, including the expansion of Fort Bellefontaine, and the construction of Fort Armstrong (1816) and Fort Edwards (1816) in Illinois, Fort Crawford (1816) in Prairie du Chien Wisconsin, Fort Snelling (1819) in Minnesota, and Fort Atkinson (1819) in Nebraska.[21]

Financing

The American government used $3 million in gold as a down payment, and issued bonds for the balance to pay France for the purchase. Earlier that year, Francis Baring and Company of London had become the U.S. government's official banking agent in London. Because of this favored position, the Baring firm was asked to handle the transaction. Francis Baring's son Alexander was in Paris at the time and helped in the negotiations. Another Baring advantage was a close relationship with Hope and Company of Amsterdam. The two banking houses worked together to facilitate and underwrite the Purchase. Because Napoleon wanted to receive his money as quickly as possible, the two firms received the American bonds and paid cash to France.[22]

The original sales document of the Louisiana Purchase was exhibited in the entrance hall of the Barings London offices until the bank's collapse in 1995 and is now in the custody of ING Group, which purchased Barings.[23]

The original handwritten proclamation signed by President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison, that informed the American public of the landmark deal of the Louisiana Purchase, was acquired in 1996 by Walter Scott Jr. in Omaha, NE and now is currently in his private collection.[24]

Nature of sale

It has been asserted that what was purchased was France's claim only, not the actual territory, which belonged to the tribes which inhabited the area. The territory itself was acquired slowly throughout the nineteenth century by purchases from Native American tribes and wars.[25] The question is discussed at length in the article on Aboriginal title in the United States, as well as in articles on the American Indian Wars and the U.S. Supreme Court case Johnson v. M'Intosh.

The issue of legitimacy of the Louisiana Purchase is similar to the 1867 Alaska Purchase. In that case, the land rights were resolved more than 100 years later with the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA), and even this act resulted in lingering resentment over the Alaska Federation of Natives' lack of legitimacy to act on behalf of Alaskan natives.[26][27] See also Indian Land Claims Settlements for other cases where native land title claims were extinguished with monetary compensation.

The proceeds

Despite issuing orders that the 60 million francs were to be spent on the construction of five new canals in France, Bonaparte actually spent the whole amount on his planned invasion of the United Kingdom.[28]

See also

- Franco-American alliance

- List of French possessions and colonies

- Historic regions of the United States

- Territorial evolution of the United States

- Territories of Spain that encompassed land that was part of the Louisiana Purchase:

- Florida, 1565–1763

- Santa Fé de Nuevo Méjico, 1598–1821

- Tejas, 1690–1821

- Luisiana, 1764–1803

- Florida Occidental, 1783–1821

- Territory of France that encompassed land that was part of the Louisiana Purchase:

- Louisiane, 1682–1764 and 1803

- U.S. territories that encompassed land that was part of the Louisiana Purchase:

- Territory of Orleans, 1804–1812

- District of Louisiana, 1804–1805

- Territory of Louisiana, 1805–1812

- Territory of Missouri, 1812–1821

- Territory of Arkansas, 1819–1836

- Indian Territory, 1834–1907

- Territory of Iowa, 1838–1849

- Territory of Minnesota, 1849–1858

- Territory of New Mexico, 1850–1912

- Territory of Kansas, 1854–1861

- Territory of Nebraska, 1854–1867

- Territory of Colorado, 1861–1876

- Territory of Dakota, 1861–1889

- Territory of Montana, 1864–1889

- Territory of Wyoming, 1868–1890

- Territory of Oklahoma, 1890–1907

- U.S. states that encompass land that was part of the Louisiana Purchase:

- State of Louisiana, 1812

- State of Missouri, 1821

- State of Arkansas, 1836

- State of Texas, 1845

- State of Iowa, 1849

- State of Minnesota, 1858

- State of Kansas, 1861

- State of Nebraska, 1867

- State of Colorado, 1876

- State of North Dakota, 1889

- State of South Dakota, 1889

- State of Montana, 1889

- State of Wyoming, 1890

- State of Oklahoma, 1907

- State of New Mexico, 1912

- Territories of Spain that encompassed land that was part of the Louisiana Purchase:

- Territorial evolution of Canada

- Provinces of Canada that encompass land in the Missouri River drainage basin:

- Saskatchewan, 1905

- Alberta, 1905

- Provinces of Canada that encompass land in the Missouri River drainage basin:

References

- ^ The American Pageant by David M. Kennedy, Lizabeth Cohen, and Thomas A. Bailey

- ^ a b Table 1.1 Acquisition of the Public Domain 1781–1867

- ^ "Louisiana Purchase". Lsm.crt.state.la.us. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Louisiana Resident Population and Apportionment of the U.S. House of Representatives(PDF) U.S. Census Bureau

- ^ a b c Herring, George. "From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776". p104. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ^ Godlewski, Guy; Napoléon et Les-États-Amis, P.320, La Nouvelle Revue Des Deux Mondes, July–September 1977.

- ^ a b Herring, George. "From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776". p99. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ^ Meinig, D.W. The Shaping of America: Volume 2, Yale University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-300-06290-7

- ^ a b Herring, George. "From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776". p100. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ^ Duke, Marc; The du Ponts: Portrait of a Dynasty, P.77–83, Saturday Review Press, 1977

- ^ "The Haitian Revolution". Scholar.library.miami.edu. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Herring, George. "From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776". p101. Oxford University Press, 2008.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Malone, Michael P. (1991). Montana—A History of Two Centuries. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 30. ISBN 0295971290.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Thomas, Fleming(2003). The Louisiana Purchase. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., P:149

- ^ a b c Nugent, Walter (2009). Habits of Empire: A History of American Expansionism. Random House. pp. 65–68. ISBN 9781400078189. Retrieved 17 December 2010.

- ^ "America's Louisiana Purchase: Noble Bargain, Difficult Journey". Lpb.org. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Schoultz, Lars (1998). Beneath the United States. Harvard University Press. pp. 15–16. ISBN 9780674922761. online at Google Books

- ^ Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- ^ Weber, David J. (1994). The Spanish Frontier in North America. Yale University Press. pp. 223, 293. ISBN 9780300059175. online at Google Books

- ^ Prucha, Francis P. (1969) The Sword of the Republic: The United States Army on the Frontier 1783–1846. Macmillan, New York

- ^ Ziegler, Philip (1988). The Sixth Great Power: Barings 1762–1929. London: Collins. ISBN 0-002-17508-8.

- ^ "in print: project ING / Barings Archive client ING". tuch design. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ "Louisiana Purchase Manuscript Goes on Public Display". News.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 2010-06-11.

- ^ Loewen, James. Lies My Teacher Told Me. Touchstone, 2007, p. 121-122. ISBN 978-0-7432-9628-1

- ^ http://www.alaskool.org/projects/ancsa/articles/ADN/RyanOlsenDec2004.htm

- ^ http://www.akhistorycourse.org/articles/article.php?artID=280

- ^ >The Louisiana Purchase, Thomas J. Fleming, John Wiley & Sons Inc. 2003, ISBN 0-471-26738-4 (p.129-130)

External links

- Text of the Louisiana Purchase Treaty

- Library of Congress – Louisiana Purchase Treaty

- Teaching about the Louisiana Purchase

- Louisiana Purchase Bicentennial 1803–2003

- New Orleans/Louisiana Purchase 1803

- The Haitian Revolution and the Louisiana Purchase

- Lewis and Clark Trail

- Louisiana Purchase and Lewis & Clark student and teacher guide: dates, people, analysis, multimedia

- Case and Controversies in U.S. History, Page 42 Senator Pickering explains his opposition to the Louisiana Purchase, 1803.