MC Ren

MC Ren | |

|---|---|

MC Ren in 1990 | |

| Born | Lorenzo Jerald Patterson June 16, 1969 Compton, California, U.S. |

| Other names |

|

| Education | Dominguez High School |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1987–present |

| Spouse |

Yaasamen Alaa (m. 1993) |

| Children | 5 |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instrument | |

| Labels |

|

| Formerly of | N.W.A |

Lorenzo Jerald Patterson (born June 16, 1969),[1] known professionally as MC Ren, is an American rapper, songwriter, and record producer from Compton, California. He is the founder and owner of the independent record label Villain Entertainment.

MC Ren began his career as a solo artist signed to Eazy-E's Ruthless Records in early 1987, while still attending high school. By the end of 1987, after having written nearly half of Eazy-Duz-It, he became a member of N.W.A. After the group disbanded in 1991, he stayed with Ruthless, releasing three solo albums including the controversial Shock of the Hour before leaving the label in 1998.[2][3]

In 2016, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of N.W.A.[4][5][6]

In 2024, he received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award as a member of N.W.A. He showed up to the ceremony to accept the award along with Ice Cube, DJ Yella, The D.O.C and Lil Eazy E.[7][8]

Early life

[edit]Lorenzo Jerald Patterson was born in Compton, California, on June 16, 1969,[9] and raised in Pannes Ave. around Kelly Park. He grew up with his parents, two brothers and a sister. His father used to work for "the government", until he later opened up his own barber shop.[10] Patterson joined the Kelly Park Compton Crips (of which Eazy-E would also become a member) in attempt to make money, but soon departed and turned to drug dealing as he felt it was more lucrative. Following a raid on his childhood friend MC Chip's house, Patterson quit dealing and focused thereafter on making music.[11]

Patterson attended Dominguez High School, where he met his future collaborator, DJ Train. At this time, he developed an interest in hip hop music, and began writing songs with MC Chip, with whom he formed the group Awesome Crew, and performed at parties and nightclubs.[12] Patterson officially began his rap career upon joining forces with another childhood friend, Eric "Eazy-E" Wright, in 1985.[13] Patterson graduated from high school in 1987 and he planned to join the United States Army after graduation, but changed his mind after watching the 1987 film Full Metal Jacket.

Music career

[edit]Career beginnings: 1987–1991

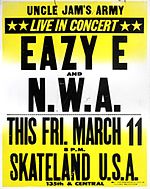

[edit]In 1987, Patterson was signed as a solo artist to Eazy-E's Ruthless Records, while still attending high school. However, when Ice Cube went to study for a year, Ren was asked to write songs for the in-progress Eazy-Duz-It. After writing much of the album, MC Ren was asked to join the group N.W.A. They immediately started on the album Straight Outta Compton. With a budget of US$8,000, the album was finished in four weeks and released in August 1988.[14] Propelled by "Fuck tha Police", the album became a major success, despite an almost complete absence of radio airplay or major concert tours. The FBI sent Ruthless a warning letter in response to the song's content.[15][16]

One month after Straight Outta Compton, Eazy-Duz-It was released, with lyrics largely written by Patterson, with contributions from Ice Cube and The D.O.C.[17]

Following Ice Cube's departure from the group in 1989, N.W.A quickly released the EP 100 Miles and Runnin'[18][19] with lyrics written by Patterson, with contributions by The D.O.C. The group's second full-length studio album, Niggaz4Life, was released the next year.[20] Selling 955,000 copies in the 1st week and was certified as Platinum,[21] it became the first rap album to enter #1 on the Billboard charts.[22] This album would become the group's final, as Dr. Dre left the group over financial disputes with Jerry Heller.

According to Patterson, it was common opinion that Heller was the one receiving their due:

We felt he didn't deserve what he was getting. We deserved that shit. We were the ones making the records, traveling in vans and driving all around the place. You do all those fucking shows trying to get known, and then you come home to a fucking apartment. Then you go to his house, and this motherfucker lives in a mansion. There's gold leaf trimmings all in the bathroom and all kinds of other shit. You're thinking, "Man, fuck that."[23]

Solo career: 1992–present

[edit]As N.W.A disbanded, Patterson started recording his first solo release titled Kizz My Black Azz. The 6-track EP was entirely produced by DJ Bobcat, except for one song that Patterson produced himself. Released in summer 1992, the EP was a hit, commercially and critically. Without any radio play, the EP went Platinum within 2 months.[24][25]

Patterson began recording for his debut album, at that time called Life Sentence, in late 1992. During the recording process, Patterson joined The Nation of Islam with guidance from DJ Train. This caused him to scrap Life Sentence, and Shock of the Hour was released in late 1993.[26] The album debuted at #1 on the R&B charts, selling 321,000 copies in its first month. Shock of the Hour was regarded as being more focused, yet even more controversial, and critics accused him again of being anti-white, misogynist, and antisemitic.[27][28] The album is thematically divided into two sides; the first half deals with social issues like ghetto life, drug addiction, racism and poverty. The second half shows Patterson's political side, as that half was recorded after he joined the Nation of Islam. The album features the hit singles "Same Ol' Shit" and "Mayday on the Frontline".

After 2 years of not talking to each other, Patterson reunited with Eazy-E in 1994 to produce their duet song "Tha Muthpukkin' Real" produced by DJ Yella, with Patterson co-producing. Three months later; on March 26, 1995, Eazy-E would die from complications of AIDS. The song "Tha Muthpukkin' Real" was released as a single in 1995.

Patterson soon fell on hard times when both DJ Train and Eazy-E died before the release of The Villain in Black. The album, which was released in early 1996 and represented Patterson's first attempt at imitating the G-funk sound of Dr. Dre's The Chronic, was not well received by critics.[29] It was also heavily criticized for what many saw as Patterson's pandering to gangsta rap at the cost of a reduction in the sociopolitical content found on his earlier releases. The album debuted at #31 on the pop-charts, with the first week's sales of 31,000 copies. By the second month it had sold 131,000 copies.

Before leaving Ruthless, Patterson released Ruthless for Life in 1998, which proved a small comeback, selling moderately well. The album features Ice Cube, Snoop Dogg, RBX and 8Ball & MJG, and others. This was the first time Patterson worked with new producers. By the end of 1998, Patterson had left Ruthless.[30][31]

On October 31, 2009, Patterson released his fourth studio album entitled Renincarnated, which was released under his own record label Villain. Renincarnated was only released in the US.

In 2015, Patterson stated that he had been working on his second EP, titled Rebel Music and released two singles: the title track, "Rebel Music", and "Burn Radio Burn". The official remix for "Rebel Music" was released in June 2014, and features Ice Cube.[32][33][34] It was originally expected to be released by the end of 2015 but remained unreleased until 2022 when he canceled the project and followed it up with a new EP, Osiris via Twitter.[35]

On May 22, 2022, he announced the track list of Osiris, and released the EP on June 3, 2022. The eight-track EP is entirely produced by Tha Chill and features guest appearances from Kurupt, Kokane, Cold 187um, Ras Kass and others.[36]

Collaborations: 1987–present

[edit]In 1988, Patterson contributed to Eazy-Duz-It. Although officially released as a solo album by Eazy-E, numerous artists contributed. Patterson; the only guest rapper on the album, features raps of his own on almost half of the album. The album was produced by Dr. Dre and DJ Yella, while Patterson, Ice Cube and The D.O.C. wrote the lyrics.

In 1990, Patterson produced the debut album for his protege group CPO, titled To Hell and Black. The group consisted of CPO Boss Hogg, DJ Train, and Young D. After the release of their debut album, the group dissolved. CPO Boss Hogg went to have a solo career, featuring on high-profile albums of N.W.A, Dr. Dre and Tupac, while DJ Train stayed with Patterson.

In 1993, Patterson introduced a new group called The Whole Click. The group featured Patterson's longtime collaborator Bigg Rocc, Grinch, Bone and Patterson's brother, Juvenile. The group first appeared on Patterson's debut album Shock of the Hour. The collective later split up. Bigg Rocc continued to collaborate with Patterson, featuring him on all his solo albums.

In 2000, he appeared on the song "Hello", which featured Dr. Dre and Ice Cube on Ice Cube's War & Peace Vol. 2 (The Peace Disc) album. He joined the Up in Smoke Tour that same year to rap his verse on the track. He also appeared on the posse cut "Some L.A. Niggaz" from Dr. Dre's 2001 album.[37]

Patterson's recent work has appeared on some more politically oriented projects with Public Enemy, specifically Paris's album Hard Truth Soldiers Vol. 1 as well as on Public Enemy's album Rebirth of a Nation. Paris stated in an interview with rapstation.com that: "MC Ren is retired and won't be doing a full-length album as far as I know. I get at him for verses, that's about it."

In April 2016, Patterson reunited with the former members of N.W.A at Coachella.[38][39]

Other ventures

[edit]Film career

[edit]In 1992, Patterson was offered the role for A-Wax in Menace II Society. Despite accepting the role, Patterson later changed his mind and the role was given to MC Eiht.[40]

In 2004, Patterson released the straight-to-DVD film Lost in the Game. The movie was produced, written and directed by Patterson, with Playboy T assisting. It was an independent movie released by Patterson's company Villain.

Patterson was portrayed by Aldis Hodge[41] in the 2015 N.W.A biopic Straight Outta Compton.[42][43][44][45]

Personal life

[edit]In June 1993, he married Yaasamen Alaa, with whom he has five children. His oldest son, Anthony, is an aspiring rapper under the name "Waxxie",[46] and has collaborated with other sons of N.W.A members.

In April 1993, Patterson began attending a mosque, and by July he was a fully registered member of the Nation of Islam, known as Lorenzo X. Two years later he left the organization and converted to Sunni Islam.[47]

Artistry

[edit]Influences

[edit]Patterson stated that KRS-One, Chuck D, Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, and Run-DMC are his biggest influences.[48] MC Ren also stated Criminal Minded by Boogie Down Productions as his all-time favorite hip hop album.[49]

Legacy

[edit]In 2024, MC Ren was awarded a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award as a member of N.W.A.[50]

Discography

[edit]

Studio albums

- Shock of the Hour (1993)

- The Villain in Black (1996)

- Ruthless for Life (1998)

- Renincarnated (2009)

Collaborative albums

- Straight Outta Compton (with N.W.A) (1988)

- 100 Miles and Runnin' (with N.W.A) (1990)

- Niggaz4Life (with N.W.A) (1991)

Extended plays

- Kizz My Black Azz (1992)

- Osiris (2022)

Filmography

[edit]| Films | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

| 1993 | Niggaz4Life: The Only Home Video | Himself | Documentary |

| 2000 | Up in Smoke Tour | Himself | Concert film |

| 2005 | Lost in the Game | The Vill | Main role |

| 2017 | The Defiant Ones | Himself | TV documentary |

| Biographical portrayals in film | |||

| Year | Title | Portrayed by | Notes |

| 2015 | Straight Outta Compton | Aldis Hodge | Biographical film about N.W.A |

| 2016 | Surviving Compton: Dre, Suge & Michel'le | Daniel DeBoe | Biographical film about Michel'le |

References

[edit]- ^ "Happy Birthday, MC Ren! - XXL". XXL Magazine. June 16, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ "Here's What MC Ren Has Been Up To Since N.W.A". Bustle. August 14, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ "MC Ren". Villain Nation. Archived from the original on January 7, 2019. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ "N.W.A | Rock & Roll Hall of Fame". www.rockhall.com. Retrieved April 26, 2021.

- ^ "NWA inducted to Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". BBC News. April 10, 2016. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ Seabrook III, Robby (April 8, 2018). "Today in Hip-Hop: N.W.A Inducted Into Rock & Roll Hall of Fame - XXL". XXL Magazine. Retrieved April 8, 2018.

- ^ Aswad, Jem (January 5, 2024). "N.W.A, Laurie Anderson, Gladys Knight, More to Receive 2024 Grammy Lifetime Achievement Awards". Variety. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ Ju, Shirley (February 6, 2024). "Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Honors N.W.A with Lifetime Achievement Award At 2024 Grammys". The Source. Retrieved February 7, 2024.

- ^ Huey, Steve. "MC Ren – Biography". AllMusic. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ Raider, Tusken (December 7, 2007). "29 MC Ren interview 1 Hip Hop Connection February 1994 NO.60.jpg | Flickr – Photo Sharing!". Flickr. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ Raider, Tusken (December 7, 2007). "41 MC Ren interview 1 The Source February 1994 NO.53". Flickr. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ Westhoff, Ben (June 16, 2014). "MC Ren Comes Out Swinging on His New Single". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ "// MC Ren Interview (October 2008) // West Coast News Network //". Dubcnn.com. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ Headley, Maxine. "BBC - Music - Review of N.W.A - Straight Outta Compton". BBC. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ "Compton Rappers Versus the Letter of the Law : FBI Claims Song by N.W.A. Advocates Violence on Police". Los Angeles Times. October 5, 1989.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (October 4, 1989). "THE FBI AS MUSIC CRITIC". Washington Post.

- ^ McDermott, Terry (2002-04-14). "Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Old music: 100 Miles and Runnin'". The Guardian. June 19, 2012.

- ^ Allah, Sha Be (August 14, 2020). "Today in Hip-Hop History: N.W.A.'s Second LP '100 Miles And Runnin' Turns 30!". The Source.

- ^ Grow, Kory (May 29, 2016). "N.W.A Reflect on 'Efil4zaggin,' 1991's Most Dangerous Album". Rolling Stone.

- ^ "American album certifications – N.W.A. – EFIL4ZAGGIN". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ "N.W.A Chart History (Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Burgess, Omar (October 26, 2008). "MC Ren: RenIncarnated". Hiphop DX. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved April 18, 2011.

- ^ James Bernard (September 1992). "Kizz My Black Azz; Return of the Product". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022.

- ^ "American album certifications – MC Ren – Kizz My Black Azz". Recording Industry Association of America. Retrieved January 15, 2022.

- ^ Gold, Jonathan (December 19, 1993). "M.C. REN; "Shock of the Hour"; Ruthless/Relativity". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 22, 2022. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "MC Ren Chart History: R&B/Hip-Hop Albums". Billboard. Retrieved January 24, 2022.

- ^ "Shock of the Hour [Ruthless, 1993]". robertchristgau.com/. November 23, 1993. Retrieved June 7, 2015.

- ^ Coker, Cheo Hodari (April 27, 1996). "1/2 MC Ren, "The Villain in Black," Ruthless/Relativity (**)". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 4, 2024.

- ^ Reiss, Randy (June 19, 1998). "MC Ren Gets Ruthless On New Solo Album". MTV News. Archived from the original on September 19, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ Ruthless for Life - MC Ren | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic, retrieved July 14, 2021

- ^ Westhoff, Ben (June 16, 2014). "MC Ren Comes Out Swinging on His New Single". LA Weekly.

- ^ "N.W.A. Forever: MC Ren Making New Tunes With Ice Cube, DJ Premier". VIBE. October 25, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Martins, Chris (March 27, 2014). "N.W.A. OG MC Ren Is Still Making 'Rebel Music'". SPIN.

- ^ MC Ren [@realmcren] (May 20, 2022). "NEW EP " Osiris " dropping June 3rd . The Saga continues 🔥" (Tweet). Retrieved September 15, 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "N.W.A Legend MC Ren Unveils Tha Chill-Produced 'Osiris' EP Tracklist & Release Date". HipHopDX. May 25, 2022.

- ^ "Hello". HotNewHipHop. May 25, 2017. Retrieved March 25, 2022.

- ^ "Watch Ice Cube reunite with N.W.A. members MC Ren and DJ Yella at Coachella". NME. April 17, 2016.

- ^ "N.W.A's Coachella Reunion 'Felt Like Old Times,' MC Ren Says". Rolling Stone. April 28, 2016.

- ^ "MC Eiht Praises Kendrick Lamar, Recalls DJ Quik's "Clever Line," And 2Pac's "Menace II Society" Days". hiphopdx.com. January 30, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (July 29, 2014). "Universal's 'Straight Outta Compton' Casts its MC Ren and DJ Yella". Variety.

- ^ Ford, Rebecca (July 29, 2014). "N.W.A Biopic Casts MC Ren & DJ Yella Roles". Billboard.

- ^ "MC Ren Slams N.W.A 'Straight Outta Compton' Movie Trailers: 'How the Hell You Leave Me Out?'". Billboard. June 10, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2021.

- ^ "MC Ren on 'Straight Outta Compton': "Don't Let the Movie Fool You About My Contribution"". The Hollywood Reporter. August 17, 2015. Retrieved August 17, 2015.

- ^ Child, Ben (August 18, 2015). "MC Ren praises Straight Outta Compton but laments lesser role in NWA biopic". The Guardian. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- ^ "MC Ren's Son Waxxie Pursues Rap Career, Talks Father's Influence". HipHopDX. December 12, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- ^ Burgess, Omar (October 25, 2008). "MC Ren: RenIncarnated". HipHop DX. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved May 21, 2011.

- ^ "MC Ren Confirms "Gangsta Rap" Label Began With N.W.A Newspaper Article". HipHopDX. May 22, 2014.

- ^ "MC Ren on Boogie Down Productions' "Criminal Minded" | BEST ALBUMS | Episode 36". YouTube. April 2, 2017. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021.

- ^ "The Recording Academy Announces 2024 Special Merit Award & Lifetime Achievement Award Honorees: N.W.A, Gladys Knight, Donna Summer, DJ Kool Herc & Many More". grammy.com. January 5, 2024. Archived from the original on February 4, 2024. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- MC Ren at AllMusic

- MC Ren at IMDb

- 1969 births

- Living people

- 20th-century African-American male actors

- 20th-century American male actors

- 20th-century American rappers

- 21st-century American rappers

- African-American male rappers

- African-American Sunni Muslims

- African-American songwriters

- American male film actors

- American male rappers

- American male songwriters

- Converts to Sunni Islam

- Crips

- Epic Records artists

- Former Nation of Islam members

- Gangsta rappers

- G-funk artists

- Male actors from California

- Male actors from Los Angeles

- Musicians from Compton, California

- N.W.A members

- Priority Records artists

- Rappers from Los Angeles

- Ruthless Records artists

- Songwriters from California

- Manuel Dominguez High School alumni

- Muslims from California