Brookwood Cemetery

| Brookwood Cemetery | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Established | 1852 |

| Location | |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°17′48″N 00°38′00″W / 51.29667°N 0.63333°W |

| Owned by | Woking Necropolis and Mausoleum Limited, subsidiary of Woking Borough Council (2014–present)[3] Diane Holliday (2012–2014)[4] |

| Size | 220 acres (89.0 ha)[8] |

| No. of interments | 235,000 |

| Website | Official website |

| Find a Grave | Brookwood Cemetery |

Brookwood Cemetery, also known as the London Necropolis, is a burial ground in Brookwood, Surrey, England. It is the largest cemetery in the United Kingdom and one of the largest in Europe. The cemetery is listed a Grade I site in the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[9]

History

[edit]Background

[edit]Brookwood Cemetery was conceived by the London Necropolis Company (LNC) in 1849 to house London's deceased, at a time when the capital was finding it difficult to accommodate its increasing population, both living and dead. The cemetery is said to have been landscaped by architect William Tite, but this is disputed.[10]

In 1854, Brookwood was the largest cemetery in the world but it is no longer. Its initial owner being incorporated by Act of Parliament in 1852, Brookwood Cemetery (apart from its northern section, reserved for Nonconformists) was consecrated by Charles Sumner, Bishop of Winchester, on 7 November 1854. It was opened to the public on 13 November 1854 when the first burials took place.

In 1857 actor John W. Anson acquired 1 acre (4,000 m2) of land there, the Actors' Acre, for the 'Dramatic, Equestrian and Musical Sick Fund Association' as a burial place for actors and their relatives.[11]

In 1858 the London Necropolis Company sold 64 acres (26 ha) of the extra land to the government for the building of Woking Convict Invalid Prison.[12]

Necropolis Railway

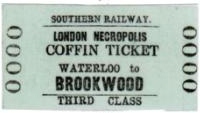

[edit]Brookwood originally was accessible by rail from a special station – the London Necropolis railway station – next to Waterloo station in Central London. Trains had passenger carriages reserved for different classes and other carriages for coffins (also for different classes), and ran into the cemetery on a dedicated branch from the adjoining South West Main Line – there was a junction just to the west of Brookwood station. From there, passengers and coffins were transported by horse-drawn vehicles. The original London Necropolis station was relocated in 1902 but its successor was demolished after suffering bomb damage during World War II.

Return tickets were issued for mourners and single tickets for the dead.[14]

There were two stations in the cemetery: North for non-conformists and South for Anglicans. Their platforms still exist along the path called Railway Avenue. For visitors wishing to use the South West Main Line, Brookwood station has provided direct access since June 1864. A very short piece of commemorative track, with signpost and plaque, purposefully gives way to a grass field and recollects the old final stage of the journey of the deceased.

It was the cholera epidemic of 1848 that led two industrialists to develop this high burial site. It was at first a controversial project. The Bishop of London condemned the "offensive" despatch of first-, second- and third-class corpses in the same carriages, so this had to be modified.

Early burials

[edit]The LNC offered three classes of funerals:

- A first class funeral allowed buyers to select the grave site of their choice anywhere in the cemetery. The LNC charged extra for burials in some designated special sites.[15] At the time of opening prices began at £2 10s (about £296 in 2025 terms) for a basic 9-by-4-foot (2.7 m × 1.2 m) with no special coffin specifications.[16][15] It was expected by the LNC that those using first class graves would erect a permanent memorial of some kind in due course following the funeral.

- Second class funerals cost £1 (about £119 in 2025 terms) and allowed some control over the burial location.[17] The right to erect a permanent memorial cost an additional 10 shillings (about £59 in 2025 terms); if a permanent memorial was not erected the LNC reserved the right to re-use the grave in future.[16][15]

- Third class funerals were reserved for pauper funerals; those buried at parish expense in the section of the cemetery designated for that parish. Although the LNC was forbidden from using mass graves (other than the burial of next of kin in the same grave) and thus even the lowest class of funeral provided a separate grave for the deceased, third class funerals were not granted the right to erect a permanent memorial on the site.[17] (The families of those buried could pay afterwards to upgrade a third class grave to a higher class if they later wanted to erect a memorial, but this practice was rare.)[18] Despite this, Brookwood's pauper graves granted more dignity to the deceased than did other graveyards and cemeteries of the period, all of which other than Brookwood continued the practice of mass graves for the poor.[19]

Brookwood was one of the few cemeteries to permit burials on Sundays, which made it a popular choice with the poor as it allowed people to attend funerals without the need to take a day off work.[20] As theatrical performances were banned on Sundays at this time, it also made Brookwood a popular choice for the burial of actors for the same reason, to the extent that actors were provided with a dedicated section of the cemetery near the station entrance.[19][21]

While the majority of burials conducted by the LNC (around 80%) were pauper funerals on behalf of London parishes and prisons,[18] the LNC also reached agreement with a number of societies, guilds, religious bodies and similar organisations (such as Woking Convict Invalid Prison and Tothill[22]). The LNC provided dedicated sections of the cemetery for these groups, on the basis that those who had lived or worked together in life could remain together after death.[23] Although the LNC was never able to gain the domination of London's funeral industry for which its founders had hoped, it was very successful at targeting specialist groups of artisans and trades, to the extent that it became nicknamed "the Westminster Abbey of the middle classes".[24] The Royal Hospital Chelsea, which previously buried their inmate pensioners at Brompton Cemetery in Chelsea, have used Brookwood Cemetery, where they have two plots, since 1893.[25]

A large number of these dedicated plots were established, ranging from Chelsea Pensioners and the Ancient Order of Foresters to the Corps of Commissionaires and the LSWR.[26] The Nonconformist cemetery also includes a Parsee burial ground established in 1862, which as of 2011[update] remained the only Zoroastrian burial ground in Europe.[27] Dedicated sections in the Anglican cemetery were also reserved for burials from those parishes which had made burial arrangements with the LNC.[28]

The first burial was of the stillborn twins of a Mr and Mrs Hore of Ewer Street, The Borough.[29] The Hore twins, along with the other burials on the first day, were pauper funerals and buried in unmarked graves.[29] The first burial at Brookwood with a permanent memorial was that of Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Goldfinch, buried on 25 November 1854, the 26th person to be buried in the cemetery.[30] The first permanent memorial erected in the Nonconformist section of the cemetery was that of Charles Milligan Hogg, son of botanist Robert Hogg, buried on 12 December 1854.[31] Goldfinch and Hogg's graves are not the oldest monuments in the cemetery, as on occasion gravestones were relocated and re-erected during the relocation of existing burial grounds to Brookwood.[32]

Over 235,000 people have been buried there.

Reburials

[edit]The massive London civil engineering projects of the mid-19th century—the railways, the sewer system and from the 1860s the precursors to the London Underground—often necessitated the demolition of existing churchyards.[33] The first major relocation took place in 1862, when the construction of Charing Cross railway station and the routes into it necessitated the demolition of the burial ground of Cure's College in Southwark, which uncovered at least 7,950 bodies.[33] These were packed into 220 large containers, each containing 26 adults plus children, and shipped on the London Necropolis Railway to Brookwood for reburial, along with at least some of the existing headstones from the cemetery.[32]

At least 21 London burial grounds were relocated to Brookwood via the railway, along with numerous others relocated by road following the railway's closure. Churches whose graves were relocated included:

- St Michael, Crooked Lane (demolished 1831, burial ground cleared 1987)[34]

- St Antholin, Budge Row (demolished 1875)

- All-Hallows-the-Great (demolished 1894)

- St Magnus-the-Martyr (remains removed from crypt 1894)

- All-Hallows-the-Less (destroyed in the Great Fire of London, remains removed 1896)

- St Michael Wood Street (demolished 1897)

- St Mildred, Bread Street (remains removed 1898, church destroyed in London Blitz 1941)

- St George Botolph Lane (demolished 1904)

- St Marylebone Parish Church (remains from crypt removed 1987)

- St Luke Old Street (closed 1959, remains from crypt removed 2000)[35]

- St James's Church, Piccadilly (remains removed from St. James's Garden, established 1878 on the former burial grounds of the church, from 2017–2020 due to HS2 terminal construction at Euston Station)

- The unconsecrated Cross Bones Graveyard in Southwark (closed 1853, many remains removed in successive years)[36]

Brookwood Cemetery and cremation

[edit]In 1878, the LNC sold an isolated piece of its land at Brookwood, close to St John's village, to the Cremation Society of Great Britain, on which they built Woking Crematorium, the first in Britain, in 1879.[37] While the LNC never built its own crematorium, in 1910, Lord Cadogan decided he no longer wanted to be interred in the mausoleum he had commissioned at Brookwood. This building, the largest mausoleum in the cemetery, was bought by the LNC, fitted with shelves and niches to hold urns, and used as a dedicated columbarium from then on.[38]

After 1945 cremation, up to that time an uncommon practice, became increasingly popular in Britain.[39] In 1946, the LNC obtained consent to build their own crematorium on a section of the Nonconformist cemetery which had been set aside for pauper burials, but chose not to proceed.[40] Instead, in 1945, the LNC began the construction of the Glades of Remembrance, a wooded area dedicated to the burial of cremated remains.[40] These were dedicated by Henry Montgomery Campbell, Bishop of Guildford in 1950.[40][note 1] Intentionally designed for informality, traditional gravestones and memorials were prohibited, and burials were marked only by small 2-to-3-inch (5.1 to 7.6 cm) stones.[41]

| London Necropolis Act 1956 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to confer further powers upon the London Necropolis Company Limited and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 4 & 5 Eliz. 2. c. lxviii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 5 July 1956 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

In the next decade, the cemetery came closest to having its own crematorium. Following the closure of the two Brookwood railway stations, the land surrounding the site of South station and the station's two Anglican chapels was redundant. As part of the London Necropolis Act 1956, the LNC obtained parliamentary consent to convert the disused original Anglican chapel into a crematorium, using the newer chapel for funeral services and the station building for coffin storage and as a refreshment room for those attending cremations.[42] Suffering cash flow problems and distracted by a succession of hostile takeover bids, the LNC management never proceeded with the scheme and the buildings fell into disuse.[42] The station building was demolished after being damaged by a fire in 1972, although the platform remained intact.[43]

Horticultural

[edit]With the ambition for it to become London's sole burial site in perpetuity, the LNC were aware that if their plans were successful, their Necropolis would become a site of major national importance.[29] As a consequence, the cemetery was designed with attractiveness in mind, in contrast to the squalid and congested London burial grounds and the newer suburban cemeteries which were already becoming crowded.[44][29]

The LNC aimed to create an atmosphere of perpetual spring in the cemetery, and chose the plants for the cemetery accordingly. It had already been noted that evergreen plants from North America thrived in the local soil.[28] Robert Donald, the owner of an arboretum near Woking, was contracted to supply the trees and shrubs for the cemetery.[45] The railway line through the cemetery and the major roads and paths within the cemetery were lined with giant sequoia trees, the first significant planting of these trees (only introduced to Europe in 1853) in Britain.[28] As well as the giant sequoias (also known as Wellingtonia after the recently deceased Duke of Wellington), the grounds were heavily planted with magnolia, rhododendron, coastal redwood, azalea, andromeda and monkeypuzzle, with the intention of creating perpetual greenery with large numbers of flowers and a strong floral scent throughout the cemetery.[28]

In later years the original planting of the cemetery was supplemented by numerous other tree species planted by the LNC, as well as many plants planted by mourners at burial sites and around mausolea. Between the end of LNC independence in 1959 and the cemetery's purchase by Ramadan Güney in 1985 cemetery maintenance was drastically reduced, and the spread of various plant types caused many of the non-military sections of the cemetery to revert to wilderness in this period.[46]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]In August 1914, on the outbreak of the First World War, the LNC offered to donate to the War Office 1 acre (4,000 m2) of land "for the free interment of soldiers and sailors who have returned from the front wounded and may subsequently die". The offer was not taken up until 1917, when a section of the cemetery was set aside as Brookwood Military Cemetery, used for the burials of service personnel who died in the London District.[38] This purpose built cemetery came to accommodate further dead from World War II.

In the meantime, 141 Commonwealth service personnel were buried from London in scattered graves throughout the cemetery, apart from a small Nurses' Plot in St Peter's Avenue in the Westminster field (where are buried nurses from Millbank Military Hospital) and an Indian plot (including one unidentified soldier) in the North-West corner.[47]

In World War II 51 Commonwealth service personnel were buried in the civilian cemetery, where there are also buried five foreign national servicemen whose graves the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) additionally care for.[47] A military memorial to the missing from that war was built in 1958 by the CWGC.

Edward the Martyr,[48] King of England, was memorialised here. His relics are kept nearby in St Edward the Martyr Orthodox Church.

| Brookwood Cemetery Act 1975 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to empower Brookwood Cemetery Limited to dispose of certain lands belonging to the said Company not required for cemetery purposes free from restrictions; to confer powers on the Company with respect to agreements with local authorities and others; and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 1975 c. xxxv |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 12 November 1975 |

The London Necropolis Company was taken over by Alliance Property in 1959[49] and the company was gradually divested of land and investments until by 1973, the cemetery was an independent entity. The cemetery changed hands between various development companies in the 1970s, during which time the cemetery maintenance was neglected: 1970 Cornwall Property (Holdings) Ltd, 1971 Great Southern Group, 1973 Maximillian Investments.[50] Maximillian Investments secured the passing of the Brookwood Cemetery Act 1975 which authorised them to sell unused parts of the cemetery [51] and a few areas were sold for development.

In 1985, Ramadan Güney acquired Brookwood Cemetery from the owner Mr D. J. T. Dally, who was previously the cemetery manager.[7] The purchase evolved from Güney's role as Chairman of the UK Turkish Islamic Trust, which wanted suitable burial facilities for its members.[6] The Brookwood Cemetery Society was founded in 1992 to organise events, promote the site's history and support restoration work. After Güney's death in 2006 he was buried in the cemetery and ownership passed to his children (by his late wife) and operated by his son Erkin, a director at the cemetery for almost 30 years. Diane Holliday, Güney's partner of 6 years, was "frozen out" from the operating company and then dismissed.[4] In 2011, the inheritance of the cemetery was successfully challenged by Diane Holliday and her adult son Kevin.[5] This decision was upheld by the High Court on appeal in 2012.[4] In 2014, Diane Holliday sold the cemetery to Woking Council.[3]

In 2017, work began on the exhumation of the remains of approximately 40,000 to 50,000 people who were interred at the former burial ground of St. James's Church[52] due to construction of the new HS2 terminal at Euston Station in London.[53] The former burial ground had been in use between 1790 and 1853 before the cemetery became St James's Gardens in 1878. The grounds had been utilised as public park space until they were closed in 2017 at the outset of construction.[53] A large part of the exhumation project consisted of a multi-year cataloguing and study of the remains by osteo-archaeologists, part of which was documented by the BBC.[54] In 2020 it was announced that it had been agreed by the Woking Council and HS2 that the remains were to be re-interred in a new grassland plot on the south side of Brookwood Cemetery.[55] The exhumations and study began in October 2018 and the re-interment at Brookwood took place sometime around August 2020 to November 2020.[56] At around 50,000 individual remains, it is thought to be the largest single reburial project in the history of Brookwood.[56]

Brookwood Military Cemetery and memorials

[edit]

Brookwood Military Cemetery covers about 37 acres (15 ha) and is the largest Commonwealth war cemetery in the United Kingdom. The land was set aside during World War I to provide a burial site for men and women of Commonwealth and American armed forces who died in the United Kingdom of wounds and other causes. It now contains 1,601 Commonwealth burials from World War I and 3,476 from World War II (the latter including 3 unidentified British and 2 unidentified Canadian airmen).

Within this, there is a particularly large Canadian section, which includes 43 men who died of wounds following the Dieppe Raid in August 1942. Two dozen Muslim dead were also later transferred here in 1968 from the Muslim Burial Ground at Horsell Common. There is a large Royal Air Force section in the southeast corner of the cemetery which includes graves of Czech and United States nationals who died serving in the RAF.

The cemetery also has 786 non-Commonwealth war graves, including 28 unidentified French, besides eight German dead from World War I and 46 from World War II.[57] It also contains Polish (84 graves), Czech, Belgian (46 graves), Dutch (seven graves) and Italian (over 300 graves) sections.[58] Except for Christmas Day and New Year's Day, this cemetery is open to the public from 8am to sunset Monday to Friday, and 9am to sunset Saturdays and Sundays.[59]

The United Kingdom 1914–1918 Memorial originally stood at the northeastern end of the 1914–1918 Plot. The new memorial that replaced it was created in 2004, and currently (17 November 2024) commemorates 407 Commonwealth service personnel who died in the First World War in the United Kingdom but have no known grave. The majority of the casualties commemorated on the Brookwood 1914–1918 Memorial are servicemen and women identified by the In From The Cold Project as having died while in care of their families and were not commemorated by the Commission at the time. (Those whose graves are subsequently discovered become commemorated under the respective cemetery.)[60]

The Brookwood Memorial stands at the southern end of the Canadian section of the cemetery and commemorates 3,428 Commonwealth men and women who died during the Second World War and have no known grave. This includes commandos killed in the Dieppe and St Nazaire Raids; and Special Operations Executive personnel who died in occupied Europe. The Brookwood Memorial also honours 199 Canadian servicemen and women. The memorial was placed within a military cemetery near the theatre of operations.[61] The Brookwood (Russia) Memorial was erected in 1983 and dismantled in 2015. It commemorated forces of the British Commonwealth who died in Russia in World War I and World War II and were buried there. The memorial was erected originally because during the Cold War those graves were inaccessible.

-

Original 1914–1918 memorial

-

Replacement 1914–1918 memorial

-

Russia memorial

Brookwood American Cemetery and Memorial

[edit]

This 4.5-acre (1.8 ha) site lies to the west of the civilian cemetery. It contains the graves of 468 American military dead from World War I and commemorates a further 563 with no known grave.

After the entry of the United States into the Second World War the American cemetery was enlarged, with burials of US servicemen beginning in April 1942. With large numbers of American personnel based in the west of England, a dedicated rail service for the transport of bodies operated from Devonport to Brookwood. By August 1944, over 3,600 bodies had been buried in the American Military Cemetery. At this time burials were discontinued, and US casualties were from then on buried at Cambridge American Cemetery.[62]

On the authority of the Quartermaster General of the United States Army, the US servicemen buried at Brookwood during the Second World War were exhumed in January–May 1948.[63] Those whose next of kin requested it were shipped to the United States for reburial,[63] and the remaining bodies were transferred to the new cemetery outside Cambridge.[62]

Brookwood American Cemetery had also been the burial site for those US servicemen executed while serving in the United Kingdom, whose bodies had been carried to Brookwood by rail from the American execution facilities at Shepton Mallet. They were not transferred to Cambridge in 1948, but instead reburied in unmarked graves at Oise-Aisne American Cemetery Plot E, a dedicated site for US servicemen executed during the Second World War.[62] (One of those executed, David Cobb, was not transferred to Plot E but was repatriated to the US and reburied in Dothan, Alabama in 1949.) Following the removal of the US war graves, the site in which they had been buried was divided into cemeteries for the Free French forces and Italian prisoners of war.[62]

It is administered by the American Battle Monuments Commission. Close by are military cemeteries and monuments of the British Commonwealth and other allied nations.[64][65]

Parsee (Zoroastrian) burial ground

[edit]Brookwood Cemetery contains the only Parsee/Zoroastrian burial ground in Europe. Opened in November 1862 due to the first recorded death of a Parsee in Britain, it was redesigned in 1901 by Sir George Birdwood to the traditional plan of the Persian paradise. As Clarke [66] describes, "The Wadia mausoleum, in the centre of the ground, represents the seven-staged 'heavenly mountain' from which the four paths lead east, south, west and north. The new aviary, or Fire Temple, is based on designs from the ruins of a double gateway of the Palace of Xerxes, and replaced the original agiary. The planting was a herbaceous plants and flowering shrubs and trees that were originally native to Persia." Some notable burials include that of Jamshedji Tata (3 March 1839 – 19 May 1904) an Indian industrialist and philanthropist who founded the Tata Group, India's biggest conglomerate company. He established the city of Jamshedpur, D.H. Hakim, one of the founding members of the London Zoroastrian Association and whose death in 1862 was the catalyst for the opening of the burial grounds, and Bapsybanoo, Dowager Marchioness of Winchester (1902-1995), the flamboyant daughter of the Most Reverend Khurshedji Pavry, high priest of the Parsees in India.[67]

Notable graves

[edit]List of people buried in Brookwood Cemetery

(Listed in order of date of death)

- Edward the Martyr (c. 962–978), King of England (reburied from Shaftesbury Abbey 1984)

- Daniel Carlsson Solander (1733–1782), Swedish naturalist, apostle of Carl Linnaeus and scientist on James Cook's first voyage to the Pacific Ocean aboard the Endeavour (reburied from Swedish Church, Wapping in 1900s)

- Admiral Sir Edward Codrington (1770–1851), naval hero of Battles of Trafalgar and Navarino (reburied from St Peter's Church, Eaton Square 1954)

- Sir Henry Goldfinch (1781–1854), Peninsular War veteran and one of the first to be buried at the cemetery

- Thomas Manders (1797–1859), low comedian and stage actor

- Fortunatus Dwarris (1786–1860), English lawyer and author

- Robert Knox (1791–1862), notable anatomist and racial theorist involved with the Burke and Hare murders[68]

- John Lynch (c. 1833–1866), Irish nationalist

- Gustav von Franck (1807–1860), writer, painter, and founding-member Savage Club

- Rebecca Isaacs, (1828–1877), the operatic soprano

- Horatia Johnson (née Ward) (1833–1890), granddaughter of Horatio Nelson and Emma Hamilton

- Charles Bradlaugh (1833–1891), atheist and political activist[69] and his daughter Hypatia Bradlaugh Bonner (1858–1935), peace activist, author, atheist and freethinker (latter after cremation)

- The 1st Viscount Sherbrooke (1811–1892), statesman

- Henri Van Laun (1820–1896), author and translator

- Alfred William Hunt (1830–1896), landscape painter, and daughter Violet Hunt (1863–1942), author and literary host

- Mary Frances Scott-Siddons (1840–1896), actress, and great-granddaughter of Sarah Siddons.

- Daniel Nicols (1833–1897), founder of the Café Royal

- Giulio Salviati (1843–1898), glassmaker of the Salviati family

- Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner (1840–1899), Anglo-Hungarian orientalist[70]

- Elaine Maynard Falkiner née Farmer (1871–1900), society beauty and first wife of Leslie Falkiner

- Samuel Johnson (1830–1900) Shakespearean comedy actor

- Alexander William Williamson (1824–1904), chemical theorist, originator of the Williamson ether synthesis, and head of the chemistry department at University College, London

- Jamsetji Tata (1839–1904), Indian Industrialist and Founder of Tata Group

- Ross Lowis Mangles (1833–1905), the first civilian to be awarded the VC[71] and one of 12 holders of the same award who are buried in the cemetery

- Lord Edward Clinton (1836–1907), politician and soldier

- Robert Ashington Bullen (1850–1912), priest, geologist and conchologist

- Dugald Drummond (1840–1912), Scottish locomotive engineer

- Allan Octavian Hume (1829–1912), Founder of Indian National Congress, civil servant, political reformer and amateur ornithologist and horticulturalist in British India

- Arthur Dukinfield Darbishire FRSE (1879–1915), geneticist

- Bernhard Ringrose Wise (1858–1916), Australian politician and Attorney General, amateur mile champion of Great Britain, 1879–81, Co-Founder of the Amateur Athletic Association

- John Wrightson (1840–1916), pioneer in agricultural education and reputedly Britain's first surfer

- William De Morgan (1839–1917), potter and tile designer

- Commander the 5th Baron Abinger (1871–1917), hereditary peer and naval officer, one of the WWI war graves here[72]

- Sir John Wolfe Barry (1836–1918), civil engineer, architect of Barry Docks, Wales

- Lieutenant Dudley Beaumont (1877–1918), army officer, painter and husband of the Dame of Sark[73]

- Sir Ratanji Tata (1871–1918), Indian businessman and philanthropist

- Edward Compton (1854–1918), actor-manager

- Edmund Baron Hartley (1847–1919), Victoria Cross recipient

- Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919), English painter

- Edith Thompson (1893–1923), executed in Holloway prison in 1923.[74] Exhumed in 2018 and buried with her parents in City of London Cemetery[75]

- John Singer Sargent (1856–1925), American artist[76]

- Alexis Theodorovich Aladin (1873–1927), Russian politician who formed and led the Trudoviks

- Luke Fildes (1843–1927), painter

- Sarah Eleanor Smith (née Pennington) (1861–1931) wife of the captain of the Titanic Edward J. Smith, buried a few feet from Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon

- Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon (1862–1931) baronet, sportsman and Titanic survivor[77]

- Abdul Rahman Andak (1859–1931), senior Malaysian civil servant, exiled to London in 1909

- Sir Dorabji Tata (1859–1932), Indian philanthropist

- Abdullah Quilliam (1856–1932), 19th-century convert from Christianity to Islam, noted for founding England's first mosque and Islamic centre [78]

- Field Marshal Sir William Robert Robertson, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, DSO (1860–1933), Chief of the Imperial General Staff (CIGS) during the First World War

- Ernest William Moir (1862–1933), civil engineer, 1st Baronet of Whitehanger and Margaret, Lady Moir (1864–1942) engineer and campaigner for women's rights

- Shapurji Saklatvala (1874–1936), Indian-born British Labour and Communist MP, and nephew of Jamsetji Tata (following cremation)[79]

- Marmaduke Pickthall (1875–1936), Western Islamic scholar, novelist, and British Muslim revert who translated the qur'an into English.

- Michael O'Dwyer (1864–1940), assassinated former Lieutenant Governor of Punjab

- Stanley Spooner (1856–1940), editor and journalist. The creator of Flight magazine.

- Tadeusz Kutrzeba (1885–1948), Polish Army general (original burial place, ashes reburied at Powazki Military Cemetery, Warsaw.[80]

- J. P. B. Jeejeebhoy (1891–1950), first Indian pilot in the Royal Flying Corps

- Abdullah Yusuf Ali (1872–1953), a translator of the Quran

- Caroll Gibbons (1903–1954), pianist and composer

- Styllou Christofi (1900–1954), penultimate woman executed in Britain (reburied from HMP Holloway 1971)

- A memorial to the victims in the Turkish Airforce plot (1959)

- Sir Thomas Beecham (1879–1961), conductor. Initially buried here, owing to changes at Brookwood, his remains were exhumed in 1991 and reburied in St Peter's Churchyard at Limpsfield, Surrey.[81]

- F. F. E. Yeo-Thomas (1902–1964), World War II Special Operations Executive (SOE) agent

- Said bin Taimur (1910–1972), Sultan of Muscat and Oman 1932–1970; body later repatriated and reburied at Royal Cemetery, Muscat[82]

- Aftab Ali (1907–1972), Bengali politician and social reformer

- Dennis Wheatley (1897–1977), occult and mystery writer (after cremation)

- Rebecca West (1892–1983), novelist, feminist and journalist[83]

- Alfred Bestall (1892–1986), author and illustrator of Rupert Bear

- Naji al-Ali (1937?–1987), Palestinian political cartoonist

- Hamid Mirza (1918–1988), Heir Presumptive of the Qajar dynasty

- Joe Vandeleur (1903–1988), DSO and Bar, British Army officer in World War II, served with the Irish Guards

- Margaret, Duchess of Argyll (1912–1993)

- Idries Shah (1924–1996), Sufi master and writer

- Muhammad al-Badr (1926–1996) last King of Yemen

- Dodi Fayed (1955–1997), film producer, (original burial site, subsequently moved to the Al-Fayed estate in Surrey)

- Christopher Hewett (1921–2001), actor, played Mr. Belvedere

- Ramadan Güney (1932–2006), owner of Brookwood Cemetery, 1985–2006[6]

- Zdeňka Pokorná (1905–2007), Czech liberation campaigner (following cremation)

- Maqbool Fida Husain (1915–2011), Indian painter

- Boris Berezovsky (1946–2013), Russian tycoon[84]

- Dame Zaha Hadid (1950–2016), Iraqi-born British architect

Location

[edit]Brookwood Cemetery is served by Brookwood railway station, and is located on both sides of Cemetery Pales in Woking. The Cemetery office is located in Glades House.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Monument to Lord Edward Pelham-Clinton – Brookwood Cemetery website". Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ Historic England. "Tomb of Lord Edward Pelham-Clinton (1836–1907), Brookwood Cemetery (1391044)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ a b David Stubbings, Woking Borough Council takes ownership of Brookwood Cemetery Archived 1 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, GetSurrey, 12 December 2014

- ^ a b c Joe Finnerty (18 October 2012). "Brookwood Cemetery family 'shocked' at ruling". getsurrey. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ a b Joe Finnerty (14 October 2012). "Brookwood Cemetery dispute finally resolved". getsurrey. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ a b c Brookwood Cemetery. "Ramadan H. Guney: 1932–2006". Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ a b Clarke 2006, pp. 35.

- ^ "Brookwood Cemetery". 2 November 2018.

- ^ Historic England. "Brookwood Cemetery (1001265)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ^ Clarke, John (2004). London's Necropolis: A Guide to Brookwood Cemetery. Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0750935135.

- ^ Jennie Bisset. "The Actors' Acre: a theatrical burial ground" (PDF). The Irvingite, No. 36, July 2006. The Irving Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2024.

- ^ "Woking History" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2022.

- ^ Clarke 2006, p. 162.

- ^ Clarke 2006, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Clarke 2006, p. 83.

- ^ a b UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b Clarke 2006, p. 81.

- ^ a b Clarke 2004, p. 16.

- ^ a b Clarke 2006, p. 103.

- ^ Clarke 2006, p. 91.

- ^ Clarke 2006, p. 93.

- ^ "The London Necropolis – Brookwood Cemetery, Woking, Surrey". www.workhouses.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ^ Clarke 2004, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 20.

- ^ Terry Philpot (2018). 31 London Cemeteries to Visit Before You Die. Step Beach Press Ltd. p. 159. ISBN 978-1908779298. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 18 February 2021.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 233.

- ^ a b c d Clarke 2004, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d Clarke 2004, p. 13.

- ^ Clarke 2004, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b Clarke 2006, p. 112.

- ^ a b Clarke 2006, p. 111.

- ^ Foxes have holes – A personal memoir of St Magnus the Martyr, London Bridge from 1984 to 1995, Woodgate, M.: Catholic League, 2005

- ^ Boyle, Angela; Boston, Ceridwen; Witkin, Annsofie (2005). The Archaeological Experience at St Luke's Church, Old Street, Islington (PDF). Oxford: Oxford Archaeology.

- ^ The Cross Bones Burial Ground, Redcross Way, Southwark, London. Museum of London, 1999, pp. vii, 4, 29.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 18.

- ^ a b Clarke 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 250.

- ^ a b c d Clarke 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 29.

- ^ a b Clarke 2004, p. 30.

- ^ Clarke 2006, p. 69.

- ^ The Times, 8 Nov. 1854.

- ^ Clarke 2004, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Clarke 2004, p. 31.

- ^ a b [1] Archived 21 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine CWGC Cemetery Report, Brookwood Cemetery.

- ^ "Edward the Martyr". Archived from the original on 6 November 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ^ Clarke 2006, pp. 31.

- ^ Clarke 2006, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Clarke 2006, pp. 32.

- ^ Location of St James's burial ground 51°31′43″N 0°08′13″W / 51.52849°N 0.13702°W

- ^ a b "St. James Gardens – A Casualty Of HS2". 6 August 2017. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "BBC Two Britain's Biggest Dig". Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "London's deceased from Euston's St James's Gardens to be reburied in Surrey's Brookwood Cemetery". High Speed Two Ltd. 16 September 2020. Archived from the original on 25 May 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ a b "HS2 Reburials from Euston Station". John Clarke, Historian of Brookwood Cemetery. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2022.

- ^ "Cannock Chase". Archived from the original on 31 August 2015. Retrieved 9 April 2015. German article on Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery, mentioning examples of Germans not reburied at Cannock Chase.

- ^ Breakdown obtained from casualty record in CWGC Brookwood Military Cemetery.

- ^ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission Brookwood site". Archived from the original on 4 September 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ^ "Brookwood 1914–1918 Memorial". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 9 December 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ Jacqueline Hucker. "Monuments of the First and Second World Wars". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011.

- ^ a b c d Clarke 2006, p. 126.

- ^ a b Clarke 2006, p. 67.

- ^ "Brookwood cemetery, American Battle Monuments Commission site". Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ^ "Brookwood cemetery, American Battle Monuments Commission video". Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2008.

- ^ Clarke, John M. (2018). London's Necropolis: A Guide to Brookwood Cemetery. United Kingdom: Stenlake Publishing Ltd. pp. 279–80. ISBN 9781840337334.

- ^ Clarke, John M. (2018). London's Necropolis: A Guide to Brookwood Cemetery. United Kingdom: Stenlake Publishing Ltd. p. 280. ISBN 9781840337334.

- ^ "Dr Robert Knox". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 20 March 2007.

- ^ "Charles Bradlaugh". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007.

- ^ "Dr G W Leitner". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007.

- ^ "Ross L. Mangles VC". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008.

- ^ CWGC entry Archived 4 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine Shelley Scarlett, 5th Baron Abinger.

- ^ "Casualty Details: D. J. Beaumont". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original on 20 June 2018. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Mrs Edith Thompson". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007.

- ^ Adam Lusher, Laid to rest at last: Edith Thompson, victim of a 'barbarous, misogynistic death penalty' Archived 23 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent 22 November 2018

- ^ "John Singer Sargent". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016.

- ^ "Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 25 March 2007.

- ^ https://www.yenisafak.com/en/world/profile-abdullah-quilliam-an-anglo-muslim-who-defended-islam-in-uk-3516553 Archived 23 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine | Yeni Safak

- ^ Mike Squires (2004). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 48. Oxford University Press. p. 677. ISBN 0198613989.

- ^ Juliusz Jerzy Malczewski (ed.): Powązki Communal Cemetery, former Military Cemetery in . Warsaw: Sport and Tourism, 1989, p. 60. ISBN 8321726410.

- ^ Lucas, John (2008). Thomas Beecham: An Obsession with Music. Boydell Press. p. 339. ISBN 978-1843834021.

- ^ Tony Jeapes: SAS Secret War. Operation Storm in the Middle East. Grennhill Books/Stakpole Books, London/Pennsylvania 2005, ISBN 1853675679, p. 29.

- ^ "Dame Rebecca West". tbcs.org.uk. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011.

- ^ Joe Finnerty (9 May 2013). "Russian tycoon buried at Brookwood Cemetery". getsurrey. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016.

Sources

[edit]- Clarke, John M. (2004). London's Necropolis. A Guide to Brookwood Cemetery. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0750935135.

- Clarke, John M. (2006). The Brookwood Necropolis Railway. Locomotion Papers. Vol. 143 (4th ed.). Usk: Oakwood Press. ISBN 978-0853616559.

Further reading

[edit]- Bell, Bethan (17 September 2023). "Necropolis Railway: The railway trip where only some returned". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- Clarke, John M. (1995). The Brookwood Necropolis Railway. The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0853614717. Locomotion Papers No. 143.

- Clarke, John M. An Introduction to Brookwood Cemetery 2nd Edition

- Clarke, John M. (2004). London's Necropolis: A guide to Brookwood Cemetery. The History Press. ISBN 978-0750935135.

- Clarke, John M. (2018). London's Necropolis: A guide to Brookwood Cemetery. Stenlake Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781840337334

External links

[edit]- Official website

- The Brookwood Cemetery Society

- Report on Brookwood – commissioned by the Home Office.

- English Heritage Listed Garden Entry

- Brookwood Military Cemeteries – Images of all sections of the military cemetery and burial plots and memorials. Includes allied nationals, Chelsea Pensioners, QA Nurses as well as German and Italian plots.

- Memorandum to the Select Committee on Environment, Transport and Regional Affairs by Brookwood Cemetery Ltd

- Map sources for Brookwood Cemetery

- Brookwood Cemetery at Find a Grave

- Cemetery details. Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

- Surrey County Council. "Brookwood_Cemetery". Exploring Surrey's Past. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- Aerial view from 1926, from the English Heritage "Britain from Above" archive

- Clarke, John M. (2018). London's Necropolis: A guide to Brookwood Cemetery. https://stenlake.co.uk/books/view-book.php?ref=1141

- Clarke, John M. (1995). The Brookwood Necropolis Railway. https://stenlake.co.uk/books/view-book.php?ref=855

- Cemeteries in Surrey

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries in England

- American Battle Monuments Commission

- Grade I listed parks and gardens in Surrey

- World War I cemeteries in the United Kingdom

- World War II cemeteries in the United Kingdom

- Disused railway stations in Surrey

- London Necropolis Company

- 1852 establishments in England

- Railway stations in Great Britain opened in 1854

- Railway stations in Great Britain closed in 1941