Structure

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized.[1] Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as biological organisms, minerals and chemicals. Abstract structures include data structures in computer science and musical form. Types of structure include a hierarchy (a cascade of one-to-many relationships), a network featuring many-to-many links, or a lattice featuring connections between components that are neighbors in space.

Load-bearing

[edit]

Buildings, aircraft, skeletons, anthills, beaver dams, bridges and salt domes are all examples of load-bearing structures. The results of construction are divided into buildings and non-building structures, and make up the infrastructure of a human society. Built structures are broadly divided by their varying design approaches and standards, into categories including building structures, architectural structures, civil engineering structures and mechanical structures.

The effects of loads on physical structures are determined through structural analysis, which is one of the tasks of structural engineering. The structural elements can be classified as one-dimensional (ropes, struts, beams, arches), two-dimensional (membranes, plates, slab, shells, vaults), or three-dimensional (solid masses).[2]: 2 Three-dimensional elements were the main option available to early structures such as Chichen Itza. A one-dimensional element has one dimension much larger than the other two, so the other dimensions can be neglected in calculations; however, the ratio of the smaller dimensions and the composition can determine the flexural and compressive stiffness of the element. Two-dimensional elements with a thin third dimension have little of either but can resist biaxial traction.[2]: 2–3

The structure elements are combined in structural systems. The majority of everyday load-bearing structures are section-active structures like frames, which are primarily composed of one-dimensional (bending) structures. Other types are Vector-active structures such as trusses, surface-active structures such as shells and folded plates, form-active structures such as cable or membrane structures, and hybrid structures.[3]: 134–136

Load-bearing biological structures such as bones, teeth, shells, and tendons derive their strength from a multilevel hierarchy of structures employing biominerals and proteins, at the bottom of which are collagen fibrils.[4]

Biological

[edit]

In biology, one of the properties of life is its highly ordered structure,[5] which can be observed at multiple levels such as in cells, tissues, organs, and organisms.

In another context, structure can also observed in macromolecules, particularly proteins and nucleic acids.[6] The function of these molecules is determined by their shape as well as their composition, and their structure has multiple levels. Protein structure has a four-level hierarchy. The primary structure is the sequence of amino acids that make it up. It has a peptide backbone made up of a repeated sequence of a nitrogen and two carbon atoms. The secondary structure consists of repeated patterns determined by hydrogen bonding. The two basic types are the α-helix and the β-pleated sheet. The tertiary structure is a back and forth bending of the polypeptide chain, and the quaternary structure is the way that tertiary units come together and interact.[7] Structural biology is concerned with biomolecular structure of macromolecules.[6]

Chemical

[edit]

Chemical structure refers to both molecular geometry and electronic structure. The structure can be represented by a variety of diagrams called structural formulas. Lewis structures use a dot notation to represent the valence electrons for an atom; these are the electrons that determine the role of the atom in chemical reactions.[8]: 71–72 Bonds between atoms can be represented by lines with one line for each pair of electrons that is shared. In a simplified version of such a diagram, called a skeletal formula, only carbon-carbon bonds and functional groups are shown.[9]

Atoms in a crystal have a structure that involves repetition of a basic unit called a unit cell. The atoms can be modeled as points on a lattice, and one can explore the effect of symmetry operations that include rotations about a point, reflections about a symmetry planes, and translations (movements of all the points by the same amount). Each crystal has a finite group, called the space group, of such operations that map it onto itself; there are 230 possible space groups.[10]: 125–126 By Neumann's law, the symmetry of a crystal determines what physical properties, including piezoelectricity and ferromagnetism, the crystal can have.[11]: 34–36, 91–92, 168–169

Mathematical

[edit]Musical

[edit]

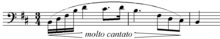

A large part of numerical analysis involves identifying and interpreting the structure of musical works. Structure can be found at the level of part of a work, the entire work, or a group of works.[12] Elements of music such as pitch, duration and timbre combine into small elements like motifs and phrases, and these in turn combine in larger structures. Not all music (for example, that of John Cage) has a hierarchical organization, but hierarchy makes it easier for a listener to understand and remember the music.[13]: 80

In analogy to linguistic terminology, motifs and phrases can be combined to make complete musical ideas such as sentences and phrases.[14][15] A larger form is known as the period. One such form that was widely used between 1600 and 1900 has two phrases, an antecedent and a consequent, with a half cadence in the middle and a full cadence at the end providing punctuation.[16]: 38–39 On a larger scale are single-movement forms such as the sonata form and the contrapuntal form, and multi-movement forms such as the symphony.[13]

Social

[edit]A social structure is a pattern of relationships. They are social organizations of individuals in various life situations. Structures are applicable to people in how a society is as a system organized by a characteristic pattern of relationships. This is known as the social organization of the group.[17]: 3 Sociologists have studied the changing structure of these groups. Structure and agency are two confronted theories about human behaviour. The debate surrounding the influence of structure and agency on human thought is one of the central issues in sociology. In this context, agency refers to the individual human capacity to act independently and make free choices. Structure here refers to factors such as social class, religion, gender, ethnicity, customs, etc. that seem to limit or influence individual opportunities.

Data

[edit]

In computer science, a data structure is a way of organizing information in a computer so that it can be used efficiently.[18] Data structures are built out of two basic types: An array has an index that can be used for immediate access to any data item (some programming languages require array size to be initialized). A linked list can be reorganized, grown or shrunk, but its elements must be accessed with a pointer that links them together in a particular order.[19]: 156 Out of these any number of other data structures can be created such as stacks, queues, trees and hash tables.[20][21]

In solving a problem, a data structure is generally an integral part of the algorithm.[22]: 5 In modern programming style, algorithms and data structures are encapsulated together in an abstract data type.[22]: ix

Software

[edit]Software architecture is the specific choices made between possible alternatives within a framework. For example, a framework might require a database and the architecture would specify the type and manufacturer of the database. The structure of software is the way in which it is partitioned into interrelated components. A key structural issue is minimizing dependencies between these components. This makes it possible to change one component without requiring changes in others.[23]: 3 The purpose of structure is to optimise for (brevity, readability, traceability, isolation and encapsulation, maintainability, extensibility, performance and efficiency), examples being: language choice, code, functions, libraries, builds, system evolution, or diagrams for flow logic and design.[24] Structural elements reflect the requirements of the application: for example, if the system requires a high fault tolerance, then a redundant structure is needed so that if a component fails it has backups.[25] A high redundancy is an essential part of the design of several systems in the Space Shuttle.[26]

Logical

[edit]As a branch of philosophy, logic is concerned with distinguishing good arguments from poor ones. A chief concern is with the structure of arguments.[27] An argument consists of one or more premises from which a conclusion is inferred.[28] The steps in this inference can be expressed in a formal way and their structure analyzed. Two basic types of inference are deduction and induction. In a valid deduction, the conclusion necessarily follows from the premises, regardless of whether they are true or not. An invalid deduction contains some error in the analysis. An inductive argument claims that if the premises are true, the conclusion is likely.[28]

See also

[edit]- Abstract structure

- Mathematical structure

- Structural geology

- Structure (mathematical logic)

- Structuralism (philosophy of science)

References

[edit]- ^ "structure, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Archived from the original on 14 June 2024. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ a b Carpinteri, Alberto (2002). Structural Mechanics: A unified approach. CRC Press. ISBN 9780203474952.

- ^ Knippers, Jan; Cremers, Jan; Gabler, Markus; Lienhard, Julian (2011). Construction manual for polymers + membranes : materials, semi-finished products, form-finding design (Engl. transl. of the 1. German ed.). München: Institut für internationale Architektur-Dokumentation. ISBN 9783034614702.

- ^ Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Y.-W.; Gao, H. (1 September 2010). "On optimal hierarchy of load-bearing biological materials". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 278 (1705): 519–525. doi:10.1098/rspb.2010.1093. PMC 3025673. PMID 20810437.

- ^ a b Urry, Lisa; Cain, Michael; Wasserman, Steven; Minorsky, Peter; Reece, Jane (2017). "Evolution, the themes of biology, and scientific inquiry". Campbell Biology (11th ed.). New York: Pearson. pp. 2–26. ISBN 978-0134093413.

- ^ a b Banaszak, Leonard J. (2000). Foundations of Structural Biology. Burlington: Elsevier. ISBN 9780080521848.

- ^ Purves, William K.; Sadava, David E.; Orians, Gordon H.; H. Craig, Heller (2003). Life, the science of biology (7th ed.). Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. pp. 41–44. ISBN 9780716798569.

- ^ DeKock, Roger L.; Gray, Harry B. (1989). Chemical structure and bonding (2nd ed.). Mill Valley, Calif.: University Science Books. ISBN 9780935702613.

- ^ Hill, Graham C.; Holman, John S. (2000). Chemistry in context (5th ed.). Walton-on-Thames: Nelson. p. 391. ISBN 9780174482765.

- ^ Ashcroft, Neil W.; Mermin, N. David (1977). Solid state physics (27. repr. ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 9780030839931.

- ^ Newnham, Robert E. (2005). Properties of materials anisotropy, symmetry, structure. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191523403.

- ^ Bent, Ian D.; Pople, Anthony. "Analysis". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 14, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ a b Meyer, Leonard B. (1973). Explaining music : essays and explorations. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press. ISBN 9780520022164.

- ^ "Sentence". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 14, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ "Phrase". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 14, 2024. Retrieved October 5, 2015.

- ^ Stein, Leon (1979). Anthology of Musical Forms: Structure & Style (Expanded Edition): The Study and Analysis of Musical Forms. Alfred Music. ISBN 9781457400940.

- ^ Lopez, J.; Scott, J. (2000). Social Structure. Buckingham and Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 9780335204960. OCLC 43708597.

- ^ Black, Paul E. (15 December 2004). "data structure". In Pieterse, Vreda; Black, Paul E. (eds.). Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures (Online ed.). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

- ^ Sedgewick, Robert; Wayne, Kevin (2011). Algorithms (4th ed.). Addison-Wesley Professional. ISBN 9780132762564.

- ^ Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2009). "Data structures". Introduction to algorithms (3rd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 229–339. ISBN 978-0262033848.

- ^ Mehta, Dinesh P. (2005). "Basic structures". In Mehta, Dinesh P.; Sahni, Sartaj (eds.). Handbook of data structures and applications. Boca Raton, Fla.: Chapman & Hall/CRC Computer and Information Science Series. ISBN 9781420035179.

- ^ a b Skiena, Steven S. (2008). "Data structures". The algorithm design manual (2nd ed.). London: Springer. pp. 366–392. ISBN 9781848000704.

- ^ Gorton, Ian (2011). Essential software architecture (2nd ed.). Berlin: Springer. ISBN 9783642191763.

- ^ Diehl, Stephan (2007). Software visualization : visualizing the structure, behaviour, and evolution of software ; with 5 tables. Berlin: Springer. pp. 38–47. ISBN 978-3540465041.

- ^ Bernardi, Simona; Merseguer, José; Petriu, Dorina Corina (2013). Model-Driven Dependability Assessment of Software Systems. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 46–47. ISBN 9783642395123.

- ^ Tomayko, James E. (March 1988). "Computers in the Space Shuttle Avionics System". Computers in Spaceflight: The NASA Experience. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ "The Structure of Arguments". Philosophy 103: Introduction to Logic. philosophy.lander.edu. Archived from the original on 9 October 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ a b Kemerling, Garth. "Arguments and Inference". The Philosophy Pages. Archived from the original on 4 June 2023. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Carpi, A.; Brebbia, C.A. (2010). Design & nature V : comparing design in nature with science and engineering. Southampton: WIT. ISBN 9781845644543.

- Pullan, Wendy (2000). Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-78258-9.

- Rottenberg, Annette T.; Winchell, Donna Haisty (2012). The structure of argument (7th ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martins. ISBN 9780312650698.

- Schlesinger, Izchak M.; Keren-Portnoy, Tamar; Parush, Tamar (2001). The structure of arguments. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins. ISBN 9789027223593.

External links

[edit]- Wüthrich, Christian. "Structure in philosophy, mathematics and physics (Phil 246, Spring 2010)" (PDF). University of California San Diego. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 October 2015. (syllabus and reading list)