List of atheists in science and technology

Appearance

(Redirected from List of atheists (Science and technology))

This is a list of atheists in science and technology. A statement by a living person that he or she does not believe in God is not a sufficient criterion for inclusion in this list. Persons in this list are people (living or not) who both have publicly identified themselves as atheists and whose atheism is relevant to their notable activities or public life.

| Part of a series on |

| Atheism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Irreligion |

|---|

A

[edit]

- Scott Aaronson (1981–): American theoretical computer scientist and professor at the University of Texas at Austin.[1] His primary area of research is quantum computing and computational complexity theory.[2]

- Ernst Abbe (1840–1905): German physicist, optometrist, entrepreneur, and social reformer. Together with Otto Schott and Carl Zeiss, he laid the foundation of modern optics. Abbe developed numerous optical instruments. He was a co-owner of Carl Zeiss AG, a German manufacturer of research microscopes, astronomical telescopes, planetariums and other optical systems.[3]

- Fay Ajzenberg-Selove (1926–2012): American nuclear physicist who was known for her experimental work in nuclear spectroscopy of light elements, and for her annual reviews of the energy levels of light atomic nuclei. She was a recipient of the 2007 National Medal of Science.[4]

- Jean le Rond d'Alembert (1717–1783): French mathematician, mechanician, physicist, philosopher, and music theorist. He was also co-editor with Denis Diderot of the Encyclopédie.[5][6]

- Zhores Alferov (1930–2019): Belarusian, Soviet, and Russian physicist who contributed substantially to the creation of modern heterostructure physics and electronics. He is an inventor of the heterotransistor and co-winner (with Herbert Kroemer and Jack Kilby) of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physics.

- Hannes Alfvén (1908–1995): Swedish electrical engineer and plasma physicist. He received the 1970 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on magnetohydrodynamics (MHD). He is best known for describing the class of MHD waves now known as Alfvén waves.[7][8][9][10]

- Jim Al-Khalili OBE (1962–): Iraqi-born British quantum physicist, author and science communicator. He is professor of Theoretical Physics and Chair in the Public Engagement in Science at the University of Surrey[11]

- Philip W. Anderson (1923–2020): American physicist. He was one of the recipients of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1977. Anderson has made contributions to the theories of localization, antiferromagnetism and high-temperature superconductivity.[12]

- Jacob Appelbaum (1983–): American computer security researcher and hacker. He is a core member of the Tor project.[13]

- François Arago (1786–1853): French mathematician, physicist, astronomer and politician.[14]

- Svante Arrhenius (1859–1927): Swedish scientist and the first Swedish Nobel Prize winner.[15]

- Abhay Ashtekar (1949–): Indian theoretical physicist. As the creator of Ashtekar variables, he is one of the founders of loop quantum gravity and its subfield loop quantum cosmology.[16]

- Larned B. Asprey (1919–2005): American chemist noted for his work on actinide, lanthanide, rare earth, and fluorine chemistry, and for his contributions to nuclear chemistry on the Manhattan Project and later at the Los Alamos National Laboratory.[17]

- Peter Atkins (1940–): English quantum chemist and professor of chemistry at Lincoln College, Oxford, in England.[18]

- Scott Atran (1952–): American-French cultural anthropologist who is Emeritus Director of Research in Anthropology at the Centre national de la recherche scientifique in Paris, Research Professor at the University of Michigan, and cofounder of ARTIS International and of the Centre for the Resolution of Intractable Conflict Archived 2018-05-14 at the Wayback Machine at Oxford University.[19]

- Julius Axelrod (1912–2004): American Nobel Prize–winning biochemist, noted for his work on the release and reuptake of catecholamine neurotransmitters and major contributions to the understanding of the pineal gland and how it is regulated during the sleep-wake cycle.[20]

B

[edit]

- Sir Edward Battersby Bailey FRS (1881–1965): British geologist, director of the British Geological Survey.[21]

- Gregory Bateson (1904–1980): English anthropologist, social scientist, linguist, visual anthropologist, semiotician and cyberneticist whose work intersected that of many other fields.[22]

- Sir Patrick Bateson FRS (1938–2017): English biologist and science writer, Emeritus Professor of ethology at the University of Cambridge and president of the Zoological Society of London.[23]

- William Bateson (1861–1926): English geneticist, a Fellow of St. John's College, Cambridge, where he eventually became Master. He was the first person to use the term "genetics" to describe the study of heredity and biological inheritance, and the chief populariser of the ideas of Gregor Mendel following their rediscovery.[24]

- George Beadle (1903–1989): American scientist in the field of genetics, and Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine laureate who, with Edward Tatum, discovered the role of genes in regulating biochemical events within cells in 1958.[25]

- John Stewart Bell FRS (1928–1990): Irish physicist. Best known for his discovery of Bell's theorem.[26][27]

- Richard E. Bellman (1920–1984): American applied mathematician, best known for his invention of dynamic programming in 1953, along with other important contributions in other fields of mathematics.[28]

- Charles H. Bennett (1943–): American physicist, information theorist and IBM Fellow at IBM Research. He is best known for his work in quantum cryptography, quantum teleportation and is one of the founding fathers of modern quantum information theory.[29]

- John Desmond Bernal (1901–1971): British biophysicist. Best known for pioneering X-ray crystallography in molecular biology.[30]

- Tim Berners-Lee (1955–): English computer scientist, best known as the inventor of the World Wide Web.[31]

- Marcellin Berthelot (1827–1907): French chemist and politician noted for the Thomsen-Berthelot principle of thermochemistry. He synthesized many organic compounds from inorganic substances and disproved the theory of vitalism.[32][33]

- Claude Louis Berthollet (1748–1822): French chemist.[34]

- Hans Bethe (1906–2005): German-American nuclear physicist, and Nobel laureate in physics for his work on the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis.[35] A versatile theoretical physicist, Bethe also made important contributions to quantum electrodynamics, nuclear physics, solid-state physics and astrophysics. During World War II, he was head of the Theoretical Division at the secret Los Alamos laboratory which developed the first atomic bombs. There he played a key role in calculating the critical mass of the weapons, and did theoretical work on the implosion method used in both the Trinity test and the "Fat Man" weapon dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.[36]

- Norman Bethune (1890–1939): Canadian physician and medical innovator.[37]

- Patrick Blackett OM, CH, FRS (1897–1974): Nobel Prize-winning English experimental physicist known for his work on cloud chambers, cosmic rays, and paleomagnetism.[38]

- Colin Blakemore (1944–2022): British neurobiologist, specialising in vision and the development of the brain, who is Professor of Neuroscience and Philosophy in the School of Advanced Study, University of London and Emeritus Professor of Neuroscience at the University of Oxford.[39]

- Christian Bohr (1855–1911): Danish physician; father of physicist and Nobel laureate Niels Bohr, and of mathematician Harald Bohr; grandfather of physicist and Nobel laureate Aage Bohr. Christian Bohr is known for having characterized respiratory dead space and described the Bohr effect.[40]

- Niels Bohr (1885–1962): Danish physicist. Best known for his foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum mechanics, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48]

- Sir Hermann Bondi KCB, FRS (1919–2005): Anglo-Austrian mathematician and cosmologist, best known for co-developing the steady-state theory of the universe and important contributions to the theory of general relativity.[49][50]

- Paul D. Boyer (1918–2018): American biochemist and Nobel Laureate in Chemistry in 1997.[51]

- Sydney Brenner (1927–2019): South African molecular biologist and a 2002 Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine laureate, shared with Bob Horvitz and John Sulston. Brenner made significant contributions to work on the genetic code, and other areas of molecular biology while working in the Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, England.[52]

- Calvin Bridges (1889–1938): American geneticist, known especially for his work on fruit fly genetics.[53]

- Percy Williams Bridgman (1882–1961): American physicist who won the 1946 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on the physics of high pressures.[54][55]

- Louis de Broglie (1892–1987): French physicist who made groundbreaking contributions to quantum theory and won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1929.[56][57]

- Ruth Mack Brunswick (1897–1946): American psychologist, a close confidant of and collaborator with Sigmund Freud.[58]

- Mario Bunge (1919–2020): Argentine-Canadian philosopher and physicist. His philosophical writings combined scientific realism, systemism, materialism, emergentism, and other principles.[59]

- Sir Frank Macfarlane Burnet FRS FAA FRSNZ (1899–1985): Australian virologist best known for his contributions to immunology. He won the Nobel Prize in 1960 for predicting acquired immune tolerance and was best known for developing the theory of clonal selection.[60]

- Geoffrey Burnstock (1929–2020): Australian neurobiologist and President of the Autonomic Neuroscience Centre of the UCL Medical School. He is best known for coining the term purinergic signaling, which he discovered in the 1970s. He played a key role in the discovery of ATP as neurotransmitter.[61][62]

C

[edit]

- Robert Cailliau (1947–): Belgian informatics engineer and computer scientist who, together with Sir Tim Berners-Lee, developed the World Wide Web.[63]

- Sir Paul Callaghan GNZM FRS FRSNZ (1947–2012): New Zealand physicist who, as the founding director of the MacDiarmid Institute for Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology at Victoria University of Wellington, held the position of Alan MacDiarmid Professor of Physical Sciences and was President of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance.[64]

- Sean B. Carroll (1960–): American evolutionary developmental biologist, author, educator and executive producer. He is the Allan Wilson Professor of Molecular Biology and Genetics at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[65]

- Sean M. Carroll (1966–): American cosmologist and theoretical physicist specializing in dark energy and general relativity.[66]

- Raymond Cattell (1905–1998): British and American psychologist, known for his psychometric research into intrapersonal psychological structure and his exploration of many areas within empirical psychology. Cattell authored, co-authored, or edited almost 60 scholarly books, more than 500 research articles, and over 30 standardized psychometric tests, questionnaires, and rating scales and was among the most productive, but controversial psychologists of the 20th century.[67]

- James Chadwick (1891–1974): English physicist. He won the 1935 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the neutron.[68]

- Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar (1910–1995): Indian-American astrophysicist known for his theoretical work on the structure and evolution of stars. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1983.[69][70][71]

- Georges Charpak (1924–2010): French physicist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1992.[72]

- Boris Chertok (1912–2011): Prominent Soviet and Russian rocket designer, responsible for control systems of a number of ballistic missiles and spacecraft. He was the author of a four-volume book Rockets and People, the definitive source of information about the history of the Soviet space program.[73]

- William Kingdon Clifford FRS (1845–1879): English mathematician and philosopher, co-introducer of geometric algebra, the first to suggest that gravitation might be a manifestation of an underlying geometry, and coiner of the expression "mind-stuff".[74]

- Samuel T. Cohen (1921–2010): American physicist who invented the W70 warhead and is generally credited as the father of the neutron bomb.[75]

- John Horton Conway (1937–2020): British mathematician active in the theory of finite groups, knot theory, number theory, combinatorial game theory and coding theory. He is best known for the invention of the cellular automaton called Conway's Game of Life.[76]

- Sir John Cornforth FRS, FAA (1917–2013): Australian–British chemist who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1975 for his work on the stereochemistry of enzyme-catalysed reactions.[77]

- Jan Baudouin de Courtenay (1845–1929): Polish linguist and Slavist, best known for his theory of the phoneme and phonetic alternations.[78]

- Jerry Coyne (1949–): American evolutionary biologist and professor, known for his books on evolution and commentary on the intelligent design debate.[79]

- Francis Crick (1916–2004): English molecular biologist, physicist, and neuroscientist; noted for being one of the co-discoverers of the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962.[80][81][82][83][84][85][86]

- George Washington Crile (1864–1943): American surgeon. Crile is now formally recognized as the first surgeon to have succeeded in a direct blood transfusion.[87]

- Pierre Curie (1859–1906): French physicist, a pioneer in crystallography, magnetism, piezoelectricity and radioactivity, and Nobel laureate. In 1903 he received the Nobel Prize in Physics with his wife, Marie Curie, and Henri Becquerel, "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel".[88]

D

[edit]

- Sir Howard Dalton FRS (1944–2008): British microbiologist, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK's Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs from March 2002 to September 2007.[89]

- Richard Dawkins (1941–): English evolutionary biologist, creator of the concept of the meme; outspoken atheist and populariser of science, author of The God Delusion and founder of the Richard Dawkins Foundation for Reason and Science.[90]

- Christian de Duve (1917–2013): Belgian cytologist and biochemist. He made serendipitous discoveries of two cell organelles, the peroxisome and lysosome, for which he shared the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Albert Claude and George E. Palade ("for their discoveries concerning the structural and functional organization of the cell"). In addition to discovering and naming the peroxisome and lysosome, on a single occasion in 1963 he coined the scientific terms "autophagy", "endocytosis", and "exocytosis".[91][92][93][94]

- Wander Johannes de Haas (1878–1960): Dutch physicist and mathematician who is best known for the Shubnikov–de Haas effect, the de Haas–van Alphen effect and the Einstein–de Haas effect.[95]

- Augustus De Morgan (1806–1871): British mathematician and logician. He formulated De Morgan's laws and introduced the term mathematical induction, making its idea rigorous.[96][97][98]

- Arnaud Denjoy (1884–1974): French mathematician, noted for his contributions to harmonic analysis and differential equations.[99]

- David Deutsch (1953–): Israeli-British quantum physicist at the University of Oxford. He pioneered the field of quantum computation by being the first person to formulate a description for a quantum Turing machine, as well as specifying an algorithm designed to run on a quantum computer.[100]

- William G. Dever (1933–): American archaeologist, specialising in the history of Israel and the Near East in biblical times.[101]

- Jared Diamond (1937–): American geographer, historian, and author best known for his popular science books.[102]

- Paul Dirac (1902–1984): British theoretical physicist, one of the founders of quantum mechanics, predicted the existence of antimatter, and won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1933.[103][104][105][106][107][108]

- Carl Djerassi (1923–2015): Austrian-born Bulgarian-American chemist, novelist, and playwright best known for his contribution to the development of oral contraceptive pills. He also developed Pyribenzamine (tripelennamine), his first patent and one of the first commercial antihistamines[109]

- Emil du Bois-Reymond (1818–1896): German physician and physiologist, the discoverer of nerve action potential, and the father of experimental electrophysiology.[110]

- Eugene Dynkin (1924–2014): Soviet and American mathematician. He has made contributions to the fields of probability and algebra, especially semisimple Lie groups, Lie algebras, and Markov processes. The Dynkin diagram, the Dynkin system, and Dynkin's lemma are named after him.[111]

E

[edit]

- Paul Ehrenfest (1880–1933): Austrian and Dutch theoretical physicist, who made major contributions to the field of statistical mechanics and its relations with quantum mechanics, including the theory of phase transition and the Ehrenfest theorem.[112][113]

- Albert Ellis (1913–2007): American psychologist who in 1955 developed Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy.[114]

- Paul Erdős (1913–1996): Hungarian mathematician. He published more papers than any other mathematician in history, working with hundreds of collaborators. He worked on problems in combinatorics, graph theory, number theory, classical analysis, approximation theory, set theory, and probability theory.[115]

- Daniel Everett (1951–): American linguistic anthropologist and author best known for his study of the Amazon Basin's Pirahã people and their language.[116]

- Hugh Everett III (1930–1982): American physicist who first proposed the many-worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum physics, which he termed his "relative state" formulation.[117]

- Hans Eysenck (1916–1997): German psychologist and author who is best remembered for his work on intelligence and personality, though he worked in a wide range of areas. He was the founding editor of the journal Personality and Individual Differences, and authored about 80 books and more than 1600 journal articles.[118]

F

[edit]

- Gustav Fechner (1801–1887): German experimental psychologist. An early pioneer in experimental psychology and founder of psychophysics.[119]

- Leon Festinger (1919–1989): American social psychologist famous for his Theory of Cognitive Dissonance.[120]

- Richard Feynman (1918–1988): American theoretical physicist, best known for his work in renormalizing Quantum electrodynamics (QED) and his path integral formulation of quantum mechanics . He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965.[121][122][123]

- Irving Finkel (1951–): British philologist, Assyriologist, and the Assistant Keeper of Ancient Mesopotamian script, languages and cultures in the Department of the Middle East in the British Museum, where he specialises in cuneiform inscriptions on tablets of clay from ancient Mesopotamia.[124][125]

- Sir Raymond Firth CNZM, FBA (1901–2002): New Zealand ethnologist, considered to have singlehandedly created a form of British economic anthropology.[126]

- Helen Fisher (1945-2024): American biological anthropologist and member of the Center For Human Evolutionary Studies at Rutgers University.[127]

- James Franck (1882–1964): German physicist. Won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1925.[128]

- Carlos Frenk (1951–): Mexican-British cosmologist and the Ogden Professor of Fundamental Physics at Durham University, whose main interests lie in the field of cosmology, studying galaxy formation and computer simulations of cosmic structure formation.[129]

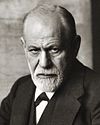

- Sigmund Freud (1856–1939): Austrian neurologist known as the father of psychoanalysis.[130]

- Jerome Isaac Friedman (1930–): American physicist who won the 1990 Nobel Prize in Physics along with Henry Kendall and Richard Taylor, for work showing an internal structure for protons later known to be quarks.[131]

- Christer Fuglesang (1957–): Swedish astronaut and physicist.[132]

G

[edit]

- George Gamow (1904–1968): Russian-born theoretical physicist and cosmologist. An early advocate and developer of Lemaître's Big Bang theory.[133][134][135][136]

- Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1772–1850): French chemist and physicist. He is known mostly for two laws related to gases.[citation needed]

- Ivar Giaever (1929–): Norwegian-American physicist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1973 with Leo Esaki and Brian Josephson "for their discoveries regarding tunnelling phenomena in solids". Giaever is an institute professor emeritus at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, a professor-at-large at the University of Oslo, and the president of Applied Biophysics.[137]

- Sheldon Glashow (1932–): American theoretical physicist. He shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics with Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam for his contribution to the electroweak unification theory.[138]

- Camillo Golgi (1843–1926): Italian physician, biologist, pathologist, scientist, and Nobel laureate. Several structures and phenomena in anatomy and physiology are named for him, including the Golgi apparatus, the Golgi tendon organ and the Golgi tendon reflex. He is recognized as the greatest neuroscientist and biologist of his time.[139][140]

- Herb Grosch (1918–2010): Canadian-American computer scientist, perhaps best known for Grosch's law, which he formulated in 1950.[141]

- David Gross (1941–): American theoretical physicist and string theorist who was awarded a Nobel Prize in Physics for his co-discovery of asymptotic freedom.[142][143][144]

H

[edit]

- Jacques Hadamard (1865–1963): French mathematician who made major contributions in number theory, complex function theory, differential geometry and partial differential equations.[145]

- Jonathan Haidt (c.1964–): Associate professor of psychology at the University of Virginia, focusing on the psychological bases of morality across different cultures, and author of The Happiness Hypothesis.[146]

- J. B. S. Haldane (1892–1964): British polymath well known for his works in physiology, genetics and evolutionary biology. He was also a mathematician making innovative contributions to statistics and biometry education in India. Haldane was also the first to construct human gene maps for haemophilia and colour blindness on the X chromosome and he was one of the first people to conceive abiogenesis.[147]

- Alan Hale (1958–): American professional astronomer, who co-discovered Comet Hale–Bopp, and specializes in the study of sun-like stars and the search for extra-solar planetary systems, and has side interests in the fields of comets and near-Earth asteroids.[148]

- Sir James Hall (1761–1832): Scottish geologist and chemist, President of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and leading figure in the Scottish Enlightenment.[149]

- G. Stanley Hall (1846–1924): Pioneering American psychologist and educator. His interests focused on childhood development and evolutionary theory. Hall was the first president of the American Psychological Association and the first president of Clark University.[150]

- Beverly Halstead (1933–1991): British paleontologist and populariser of science.[151]

- Gerhard Armauer Hansen (1841–1912): Norwegian physician, remembered for his identification of the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae in 1873 as the causative agent of leprosy.[152][153]

- G. H. Hardy (1877–1947): Prominent English mathematician, known for his achievements in number theory and mathematical analysis.[154][155]

- Herbert A. Hauptman (1917–2011): American mathematician. Along with Jerome Karle, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1985.[156]

- Stephen Hawking (1942–2018): British theoretical physicist, cosmologist, author, and Director of Research at the Centre for Theoretical Cosmology within the University of Cambridge.[157]

- Ewald Hering (1834–1918): German physiologist who did much research into color vision, binocular perception and eye movements. He proposed opponent color theory in 1892.[158][159]

- Peter Higgs (1929–2024): British theoretical physicist, recipient of the Dirac Medal and Prize, known for his prediction of the existence of a new particle, the Higgs boson, nicknamed the "God particle".[160] He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2013.

- Roald Hoffmann (1937–): American theoretical chemist who won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[161]

- Lancelot Hogben (1895–1975): English experimental zoologist and medical statistician, now best known for his popularising books on science, mathematics and language.[162]

- Brigid Hogan FRS (1943–): British developmental biologist noted for her contributions to stem cell research and transgenic technology and techniques. She is the George Barth Geller Professor of Research in Molecular Biology and Chair of the Department of Cell Biology at Duke University, as well as the director of the Duke Stem Cell Program.[163]

- Fred Hollows (1929–1993): New Zealand and Australian ophthalmologist. He became known for his work in restoring eyesight for countless thousands of people in Australia and many other countries.[164]

- Fred Hoyle (1915–2001): English astronomer noted primarily for his contribution to the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis and his often controversial stance on other cosmological and scientific matters—in particular his rejection of the "Big Bang" theory, a term originally coined by him on BBC radio.[165]

- Nicholas Humphrey (1943–): English neuropsychologist, working on consciousness and belief in the supernatural from a Darwinian perspective, and primatological research into the Machiavellian intelligence hypothesis.[166]

- Sir Julian Huxley FRS (1887–1975): English evolutionary biologist, a leading figure in the mid-twentieth century evolutionary synthesis, Secretary of the Zoological Society of London (1935–1942), the first Director of UNESCO, and a founding member of the World Wildlife Fund.[167]

I

[edit]- Saiful Islam (1963–): British materials chemist, a Professor of Materials Chemistry at the University of Bath and a recipient of the Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit award.[168]

J

[edit]- John Hughlings Jackson FRS (1835–1911): English neurologist. He is best known for his research on epilepsy. Jackson was one of the founders of the important Brain journal, which was dedicated to the interaction between experimental and clinical neurology (still being published today).[169]

- François Jacob (1920–2013): French biologist who, together with Jacques Monod, originated the idea that control of enzyme levels in all cells occurs through feedback on transcription. He shared the 1965 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Jacques Monod and André Lwoff.[170]

- Donald Johanson (1943–): American paleoanthropologist, who's known for discovering – with Yves Coppens and Maurice Taieb – the fossil of a female hominin australopithecine known as "Lucy" in the Afar Triangle region of Hadar, Ethiopia.[171][172]

- Frédéric Joliot-Curie (1900–1958): French physicist and Nobel Laureate in Chemistry in 1935.[173][174]

- Irène Joliot-Curie (1897–1956): French scientist. She is the daughter of Marie Curie and Pierre Curie. She along with her husband, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1935.[175][176]

- Steve Jones (1944–): Welsh geneticist, professor of genetics and head of the biology department at University College London, and television presenter and a prize-winning author on biology, especially evolution; one of the best known contemporary popular writers on evolution.[177][178]

K

[edit]

- Daniel Kahneman (1934–2024): Israeli psychologist and behavioral economist notable for his work on the psychology of judgment and decision-making.[179]

- Paul Kammerer (1880–1926): Austrian biologist who studied and advocated the now abandoned Lamarckian theory of inheritance – the notion that organisms may pass to their offspring characteristics they have acquired in their lifetime.[180]

- Samuel Karlin (1924–2007): American mathematician. He did extensive work in mathematical population genetics.[181]

- Grete Kellenberger-Gujer (1919–2011): Swiss molecular biologist known for her discoveries on genetic recombination and restriction modification system of DNA. She was a pioneer in the genetic analysis of bacteriophages and contributed to the early development of molecular biology.[182]

- Alfred Kinsey (1894–1956): American biologist, sexologist and professor of entomology and zoology.[183]

- Melanie Klein (1882–1960): Austrian-born British psychoanalyst who devised novel therapeutic techniques for children that influenced child psychology and contemporary psychoanalysis. She was a leading innovator in theorizing object relations theory.[184]

- Alfred Dillwyn Knox (1884–1943): British classics scholar and papyrologist at King's College, Cambridge, and a cryptologist. As a member of the World War I Room 40 codebreaking unit, he helped decrypt the Zimmermann Telegram, which brought the United States into the war. At the end of World War I, he joined the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) and on 25 July 1939, as Chief Cryptographer, participated in the Polish-French-British Warsaw meeting that disclosed Polish achievements, since December 1932, in the continuous breaking of German Enigma ciphers, thus kick-starting the British World War II Ultra operations at Bletchley Park.[185]

- Damodar Kosambi (1907–1966): Indian mathematician, statistician, historian and polymath who contributed to genetics by introducing Kosambi's map function.[186]

- Lawrence Krauss (1954–): American theoretical physicist, professor of physics at Arizona State University and popularizer of science. Krauss speaks regularly at atheist conferences such as Beyond Belief and Atheist Alliance International.[187][188]

- Harold Kroto (1939–2016): 1996 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry.[189]

- Ray Kurzweil (1948–): American inventor, futurist, and author. He is the author of several books on health, artificial intelligence (AI), transhumanism, the technological singularity, and futurism.[190]

L

[edit]

- Jacques Lacan (1901–1981): French psychoanalyst and psychiatrist who made prominent contributions to psychoanalysis and philosophy, and has been called "the most controversial psycho-analyst since Freud".[191]

- Joseph Louis Lagrange (1736–1813): Italian mathematician and astronomer that made significant contributions to the fields of analysis, number theory, and both classical and celestial mechanics.[192]

- Jérôme Lalande (1732–1807): French astronomer and writer.[193]

- Lev Landau (1908–1968): Russian physicist. He received the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physics for his development of a mathematical theory of superfluidity.[194][195]

- Alexander Langmuir (1910–1993): American epidemiologist. He is renowned for creating the Epidemic Intelligence Service.[196]

- Paul Lauterbur (1929–2007): American chemist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2003 with Peter Mansfield for his work which made the development of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) possible.[197]

- Richard Leakey (1944–2022): Kenyan paleoanthropologist, conservationist, and politician.[198]

- Félix Le Dantec (1869–1917): French biologist and philosopher of science, noted for his work on bacteria.[199]

- Leon M. Lederman (1922–2018): American physicist who, along with Melvin Schwartz and Jack Steinberger, received the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1988 for their joint research on neutrinos.[200]

- Jean-Marie Lehn (1939–): French chemist. He received the 1987 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, together with Donald Cram and Charles Pedersen.[201]

- Sir John Leslie (1766–1832): Scottish mathematician and physicist best remembered for his research into heat; he was the first person to artificially produce ice, and gave the first modern account of capillary action.[202]

- Nikolai Lobachevsky (1792–1856): Russian mathematician. Known for his works on hyperbolic geometry.[203][204]

- Jacques Loeb (1859–1924): German-born American physiologist and biologist.[205][206]

- H. Christopher Longuet-Higgins FRS (1923–2004): English theoretical chemist and a cognitive scientist.[207]

M

[edit]

- Paul MacCready (1925–2007): American aeronautical engineer. He was the founder of AeroVironment and the designer of the human-powered aircraft that won the Kremer prize.[208]

- Ernst Mach (1838–1916): Austrian physicist and philosopher. Known for his contributions to physics such as the Mach number and the study of shock waves.[209][210][211]

- Prasanta Chandra Mahalanobis FRS (1893–1972): Indian scientist and applied statistician. He is best remembered for the Mahalanobis distance, a statistical measure and for being one of the members of the first Planning commission of free india. He made pioneering studies in anthropometry in India and founded the Indian Statistical Institute.[212]

- Paolo Mantegazza (1831–1910): Italian neurologist, physiologist and anthropologist, noted for his experimental investigation of coca leaves into its effects on the human psyche.[213]

- Andrey Markov (1856–1922): Russian mathematician. He is best known for his work on stochastic processes.[214][215]

- Phil Mason (1972–): British chemist at the Institute of Organic Chemistry and Biochemistry of the Czech Academy of Sciences, who is known for his online activities and YouTube career.[216]

- Abraham Maslow (1908–1970): American psychologist. He was a professor of psychology at Brandeis University, Brooklyn College, New School for Social Research and Columbia University who created Maslow's hierarchy of needs.[217]

- Hiram Stevens Maxim (1840–1916): American-born British inventor. He invented the Maxim gun, the first portable, fully automatic machine gun; and other devices, including an elaborate mousetrap.[218][219]

- Ernst Mayr (1904–2005): Renowned taxonomist, tropical explorer, ornithologist, historian of science, and naturalist. He was one of the 20th century's leading evolutionary biologists.[220]

- John McCarthy (1927–2011): American computer scientist and cognitive scientist who received the Turing Award in 1971 for his major contributions to the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI). He was responsible for the coining of the term "Artificial Intelligence" in his 1955 proposal for the 1956 Dartmouth Conference and was the inventor of the Lisp programming language.[221][222][223]

- Sir Peter Medawar (1915–1987): Nobel Prize-winning British scientist best known for his work on how the immune system rejects or accepts tissue transplants.[224]

- Simon van der Meer (1925–2011): Dutch particle accelerator physicist who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1984 with Carlo Rubbia for contributions to the CERN project which led to the discovery of the W and Z particles, two of the most fundamental constituents of matter.[225]

- Élie Metchnikoff (1845–1916): Russian biologist, zoologist and protozoologist. He is best known for his research into the immune system. Mechnikov received the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1908, shared with Paul Ehrlich.[226]

- Marvin Minsky (1927–2016): American cognitive scientist and computer scientist in the field of artificial intelligence (AI) in MIT.[227][228]

- Peter D. Mitchell (1920–1992): 1978–Nobel-laureate British biochemist. His mother was an atheist and he himself became an atheist at the age of 15.[229]

- Jacob Moleschott (1822–1893): Dutch physiologist and writer on dietetics.[230]

- Gaspard Monge (1746–1818): French mathematician. Monge is the inventor of descriptive geometry.[34][231][232]

- Jacques Monod (1910–1976): French biologist who won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1965 for discoveries concerning genetic control of enzyme and virus synthesis.[233]

- Rita Levi-Montalcini (1909–2012): Italian neurologist who, together with colleague Stanley Cohen, received the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discovery of nerve growth factor (NGF).[234]

- Joseph-Michel Montgolfier (1740–1810): French chemist and paper-manufacturer. In 1783, he made the first ascent in a balloon (inflated with warm air).[235][236]

- Thomas Hunt Morgan (1866–1945): American evolutionary biologist, geneticist and embryologist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1933 for discoveries relating the role the chromosome plays in heredity.[237][238][239][240]

- Desmond Morris (1928–): English zoologist and ethologist, famous for describing human behaviour from a zoological perspective in his books The Naked Ape and The Human Zoo.[241][242]

- David Morrison (1940–): American astronomer and senior scientist at the Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute, at NASA Ames Research Center, whose research interests include planetary science, astrobiology, and near earth objects.[243]

- Luboš Motl (1973–): Theoretical physicist and string theorist. He said he is a Christian atheist.[244]

- Hermann Joseph Muller (1890–1967): American geneticist and educator, best known for his work on the physiological and genetic effects of radiation (X-ray mutagenesis). He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1946.[245]

- PZ Myers (1957–): American evolutionary developmental biologist at the University of Minnesota and a blogger via his blog, Pharyngula.[246]

N

[edit]

- John Forbes Nash, Jr. (1928–2015): American mathematician whose works in game theory, differential geometry, and partial differential equations. He shared the 1994 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with game theorists Reinhard Selten and John Harsanyi.[247][248]

- Yuval Ne'eman (1925–2006): Israeli theoretical physicist, military scientist, and politician. One of his greatest achievements in physics was his 1961 discovery of the classification of hadrons through the SU(3)flavour symmetry, now named the Eightfold Way, which was also proposed independently by Murray Gell-Mann.[249][250]

- Ted Nelson: (1937–): American pioneer of information technology, philosopher, and sociologist who coined the terms hypertext and hypermedia in 1963 and published them in 1965.[251]

- Alfred Nobel (1833–1896): Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor, businessman, and philanthropist who is known for inventing dynamite and holding 355 patents. He was a benefactor of the Nobel Prize.[252][253][254]

- Paul Nurse (1949–): English geneticist, President of the Royal Society and Chief Executive and Director of the Francis Crick Institute. He was awarded the 2001 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine along with Leland Hartwell and Tim Hunt for their discoveries of protein molecules that control the division (duplication) of cells in the cell cycle.[255]

O

[edit]

- Mark Oliphant (1901–2000): Australian physicist and humanitarian. He played a fundamental role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and also the development of the atomic bomb.[256]

- Alexander Oparin (1894–1980): Soviet biochemist.[257]

- Frank Oppenheimer (1912–1985): American particle physicist, professor of physics at the University of Colorado, and the founder of the Exploratorium in San Francisco. A younger brother of renowned physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, Frank Oppenheimer conducted research on aspects of nuclear physics during the time of the Manhattan Project, and made contributions to uranium enrichment.[258]

- J. Robert Oppenheimer (1904–1967): American theoretical physicist and professor of physics at the University of California, Berkeley; along with Enrico Fermi, he is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in the Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer's achievements in physics include the Born–Oppenheimer approximation for molecular wavefunctions, work on the theory of electrons and positrons, the Oppenheimer–Phillips process in nuclear fusion, and the first prediction of quantum tunneling. With his students he made important contributions to the modern theory of neutron stars and black holes, as well as to quantum mechanics, quantum field theory, and the interactions of cosmic rays.[259][260]

- Wilhelm Ostwald (1853–1932): Baltic German chemist. He received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1909 for his work on catalysis, chemical equilibria and reaction velocities. He, along with Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Svante Arrhenius, are usually credited with being the modern founders of the field of physical chemistry.[261]

P

[edit]

- Linus Pauling (1901–1994): American chemist, Nobel Laureate in Chemistry (1954) and Peace (1962)[104][262]

- John Allen Paulos (1945–): Professor of mathematics at Temple University in Philadelphia and writer, author of Irreligion: A Mathematician Explains Why the Arguments for God Just Don't Add Up (2007)[263]

- Ivan Pavlov (1849–1936): Nobel Prize–winning Russian physiologist, psychologist, and physician, widely known for first describing the phenomenon of classical conditioning.[264]

- Ruby Payne-Scott (1912–1981): Australian pioneer in radiophysics and radio astronomy, and the first female radio astronomer.[265]

- Judea Pearl (1936–): Israeli American computer scientist and philosopher, best known for championing the probabilistic approach to artificial intelligence and the development of Bayesian networks. He won the Turing Award in 2011.[266]

- Karl Pearson FRS (1857–1936): Influential English mathematician and biostatistician. He has been credited with establishing the discipline of mathematical statistics. He founded the world's first university statistics department at University College London in 1911, and contributed significantly to the field of biometrics, meteorology, theories of social Darwinism and eugenics.[267][268]

- Sir Roger Penrose (1931–): English mathematical physicist and Emeritus Rouse Ball Professor of Mathematics at the Mathematical Institute, University of Oxford and Emeritus Fellow of Wadham College. He is renowned for his work in mathematical physics, in particular his contributions to general relativity and cosmology. He is also a recreational mathematician and philosopher.[269]

- Francis Perrin (1901–1992): French physicist, co-establisher of the possibility of nuclear chain reactions and nuclear energy production.[270]

- Jean Baptiste Perrin (1870–1942): Nobel Prize–winning French physicist.[271]

- Max Perutz (1914–2002): Austrian-born British molecular biologist, who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with John Kendrew, for their studies of the structures of hemoglobin and globular proteins.[272]

- Robert Phelps (1926–2013): American mathematician who was known for his contributions to analysis, particularly to functional analysis and measure theory. He was a professor of mathematics at the University of Washington from 1962 until his death.[273]

- Steven Pinker (1954–): Canadian-American psychologist, psycholinguist, and popular science author.[274]

- Norman Pirie FRS (1907–1997): British biochemist and virologist co-discoverer in 1936 of viral crystallization, an important milestone in understanding DNA and RNA.[275]

- Henri Poincaré (1854–1912): French mathematician, theoretical physicist, engineer, and philosopher of science. He is often described as a polymath, and in mathematics as The Last Universalist, since he excelled in all fields of the discipline as it existed during his lifetime.[276][277][278]

- Carolyn Porco (1953–): American planetary scientist, known for her work in the exploration of the outer Solar System, beginning with her imaging work on the Voyager missions to Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune in the 1980s. She led the imaging science team on the Cassini mission to Saturn.[279]

- Donald Prothero (1954–): American geologist, paleontologist, and author who specializes in mammalian paleontology and magnetostratigraphy. He is the author or editor of more than 30 books and over 250 scientific papers, including five geology textbooks.[280]

R

[edit]

- Isidor Isaac Rabi (1898–1988): American physicist and Nobel Prize–winning scientist who discovered nuclear magnetic resonance in 1944 and was also one of the first scientists in the US to work on the cavity magnetron, which is used in microwave radar and microwave ovens.[281]

- Frank P. Ramsey (1903–1930): British mathematician who also made significant contributions in philosophy and economics.[282]

- Lisa Randall (1962–): American theoretical physicist working in particle physics and cosmology, and the Frank B. Baird, Jr. Professor of Science on the physics faculty of Harvard University.[283]

- Marcus J. Ranum (1962–): American computer and network security researcher and industry leader. He is credited with a number of innovations in firewalls.[284]

- Grote Reber (1911–2002): American astronomer. A pioneer of radio astronomy.[285]

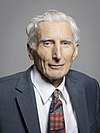

- Martin Rees, Baron Rees of Ludlow (1942–): British cosmologist and astrophysicist.[286]

- Wilhelm Reich (1897–1957): Austrian psychiatrist and psychoanalyst, known as one of the most radical figures in the history of psychiatry.[287]

- Charles Francis Richter (1900–1985): American seismologist and physicist who is most famous as the creator of the Richter magnitude scale, which, until the development of the moment magnitude scale in 1979, quantified the size of earthquakes.[288]

- Alice Roberts (1973–): English evolutionary biologist, biological anthropologist, and science communicator at the University of Birmingham.[289]

- Mark Roberts (1961–): English archaeologist specializing in the study of the Palaeolithic, and is best known for his discovery and subsequent excavations at the Lower Palaeolithic site of Boxgrove Quarry in southern England.[290]

- Richard J. Roberts (1943–): British biochemist and molecular biologist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1993 for the discovery of introns in eukaryotic DNA and the mechanism of gene-splicing.[291][292][293]

- Carl Rogers (1902–1987): American psychologist and among the founders of the humanistic approach to psychology. Rogers is widely considered to be one of the founding fathers of psychotherapy research and was honored for his pioneering research with the Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions by the American Psychological Association in 1956.[294]

- Marshall Rosenbluth (1927–2003): American physicist, nicknamed "the Pope of Plasma Physics". He created the Metropolis algorithm in statistical mechanics, derived the Rosenbluth formula in high-energy physics, and laid the foundations for instability theory in plasma physics.[295]

- Bertrand Russell (1872–1970): British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, writer, social critic and political activist. He is considered one of the founders of analytic philosophy along with his predecessor Gottlob Frege, colleague G. E. Moore, and his protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein. He is widely held to be one of the 20th century's premier logicians. With A. N. Whitehead he wrote Principia Mathematica, an attempt to create a logical basis for mathematics. His philosophical essay "On Denoting" has been considered a "paradigm of philosophy". His work has had a considerable influence on logic, mathematics, set theory, linguistics, artificial intelligence, cognitive science, computer science (see type theory and type system), and philosophy, especially the philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics.[296]

- Adam Rutherford (1975–): British geneticist, author, and broadcaster. He was an audio-visual content editor for the journal Nature for a decade, is a frequent contributor to the newspaper The Guardian, hosts the BBC Radio 4 programme Inside Science, has produced several science documentaries and has published books related to genetics and the origin of life.[297]

S

[edit]

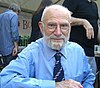

- Oliver Sacks (1933–2015): United States-based British neurologist, who has written popular books about his patients, the most famous of which is Awakenings.[298][299]

- Carl Sagan (1934–1996): American astronomer and astrochemist, a highly successful popularizer of astronomy, astrophysics, and other natural sciences, and pioneer of exobiology and promoter of the SETI. Although Sagan has been identified as an atheist according to some definitions,[300][301][302] he rejected the label, stating "An atheist has to know a lot more than I know."[300] He was an agnostic who,[303] while maintaining that the idea of a creator of the universe was difficult to disprove,[304] nevertheless disbelieved in God's existence, pending sufficient evidence.[305]

- Meghnad Saha (1893–1956): Indian astrophysicist noted for his development in 1920 of the thermal ionization equation, which has remained fundamental in all work on stellar atmospheres. This equation has been widely applied to the interpretation of stellar spectra, which are characteristic of the chemical composition of the light source. The Saha equation links the composition and appearance of the spectrum with the temperature of the light source and can thus be used to determine either the temperature of the star or the relative abundance of the chemical elements investigated.[306][307]

- Andrei Sakharov (1921–1989): Soviet nuclear physicist, dissident and human rights activist. He gained renown as the designer of the Soviet Union's Third Idea, a code name for Soviet development of thermonuclear weapons. Sakharov was an advocate of civil liberties and civil reforms in the Soviet Union. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. The Sakharov Prize, which is awarded annually by the European Parliament for people and organizations dedicated to human rights and freedoms, is named in his honor.[308][309][310]

- Robert Sapolsky (1957–): American neuroendocrinologist and professor of biology, neurology, and neurobiology at Stanford University.[311]

- Mahendralal Sarkar (1833–1904): Indian physician and academic.[312]

- Marcus du Sautoy (1965–): mathematician and holder of the Charles Simonyi Chair for the Public Understanding of Science.[313]

- Hans Joachim Schellnhuber (1950–): German atmospheric physicist, climatologist and founding director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and ex-chair of the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU).[314]

- Erwin Schrödinger (1887–1961): Austrian-Irish physicist and theoretical biologist. A pioneer of quantum mechanics and winner of the 1933 Nobel Prize for Physics.[315][316][317][318][319][320]

- Laurent Schwartz (1915–2002): French mathematician, awarded the Fields medal for his work on distributions.[321]

- Dennis W. Sciama (1926–1999): British physicist who played a major role in developing British physics after the Second World War. His most significant work was in general relativity, with and without quantum theory, and black holes. He helped revitalize the classical relativistic alternative to general relativity known as Einstein-Cartan gravity. He is considered one of the fathers of modern cosmology.[322]

- Nadrian Seeman (1945–2021): American nanotechnologist and crystallographer known for inventing the field of DNA nanotechnology.[323]

- Celâl Şengör (1955–): Turkish geologist, and currently on the faculty at Istanbul Technical University.[324]

- Claude Shannon (1916–2001): American electrical engineer and mathematician, has been called "the father of information theory", and was the founder of practical digital circuit design theory.[325][326]

- William Shockley (1910–1989): American physicist and inventor. Along with John Bardeen and Walter Houser Brattain, Shockley co-invented the transistor, for which all three were awarded the 1956 Nobel Prize in Physics.[327]

- William James Sidis (1898–1944): American mathematician, cosmologist, inventor, linguist, historian and child prodigy.[328]

- Boris Sidis (1867–1923): Russian American psychologist, physician, psychiatrist, and philosopher of education. Sidis founded the New York State Psychopathic Institute and the Journal of Abnormal Psychology. He was the father of child prodigy William James Sidis.[328]

- Ethan Siegel (1978–): American theoretical astrophysicist and science writer, whose area of research focuses on quantum mechanics and the Big Bang theory.[329]

- Herbert A. Simon (1916–2001): American Nobel laureate, was a political scientist, economist, sociologist, psychologist, computer scientist, and Richard King Mellon Professor—most notably at Carnegie Mellon University—whose research ranged across the fields of cognitive psychology, cognitive science, computer science, public administration, economics, management, philosophy of science, sociology, and political science, unified by studies of decision-making.[330]

- Michael Smith (1932–2000): British-born Canadian biochemist and Nobel Laureate in Chemistry in 1993.[331]

- John Maynard Smith (1920–2004): British theoretical evolutionary biologist and geneticist. Maynard Smith was instrumental in the application of game theory to evolution and theorised on other problems such as the evolution of sex and signalling theory.[332]

- Oliver Smithies (1925–2017): British-born American Nobel Prize–winning geneticist and physical biochemist. He is known for introducing starch as a medium for gel electrophoresis in 1955 and for the discovery, simultaneously with Mario Capecchi and Martin Evans, of the technique of homologous recombination of transgenic DNA with genomic DNA, a much more reliable method of altering animal genomes than previously used, and the technique behind gene targeting and knockout mice.[333]

- George Smoot (1945–): American astrophysicist and cosmologist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2006 for his work on the Cosmic Background Explorer with John C. Mather that led to the measurement "of the black body form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation.[334]

- Alan Sokal (1955–): American professor of physics at New York University and professor of mathematics at University College London. To the general public he is best known for his criticism of postmodernism, resulting in the Sokal affair in 1996.[335]

- Dan Sperber (1942–): French social and cognitive scientist, whose most influential work has been in the fields of cognitive anthropology and linguistic pragmatics.[336]

- Robert Spitzer (1932–2015): American psychiatrist, Professor of Psychiatry at Columbia University, a major architect of the modern classification of mental disorders.[337]

- Jack Steinberger (1921–2020): German-American-Swiss physicist and Nobel Laureate in 1988, co-discoverer of the muon neutrino.[338]

- Hugo Steinhaus (1887–1972): Polish mathematician and educator.[339]

- Victor J. Stenger (1935–2014): American physicist, emeritus professor of physics and astronomy at the University of Hawaii and adjunct professor of philosophy at the University of Colorado. Author of the book God: The Failed Hypothesis.[340][341]

- Eleazar Sukenik (1889–1953): Israeli archaeologist and professor of Hebrew University in Jerusalem, undertaking excavations in Jerusalem, and recognising the importance of the Dead Sea Scrolls to Israel.[342]

- John Sulston (1942–2018): British biologist. He is a joint winner of the 2002 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.[343]

- Leonard Susskind (1940–): American theoretical physicist; a founding father of superstring theory and professor of theoretical physics at Stanford University.[344]

- Dick Swaab (1944): Dutch physician and neurobiologist (brain researcher). He is a professor of neurobiology at the University of Amsterdam and was until 2005 Director of the Netherlands Institute for Brain Research (Nederlands Instituut voor Hersenonderzoek) of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen). He is known for his book We Are Our Brains (2010).

T

[edit]

- Igor Tamm (1895–1971): Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov and Ilya Frank, for their 1934 discovery of Cherenkov radiation.[345][346][347]

- Arthur Tansley (1871–1955): English botanist who was a pioneer in the science of ecology.[348]

- Alfred Tarski (1901–1983): Polish logician, mathematician and philosopher, a prolific author best known for his work on model theory, metamathematics, and algebraic logic.[349]

- Kip Thorne (1940–): American theoretical physicist and winner of the 2017 Nobel Prize in physics, known for his contributions in gravitational physics and astrophysics and also for the popular-science book, Black Holes and Time Warps: Einstein's Outrageous Legacy.[350]

- Nikolaas Tinbergen (1907–1988): Dutch ethologist and ornithologist who shared the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Karl von Frisch and Konrad Lorenz for their discoveries concerning organization and elicitation of individual and social behaviour patterns in animals.[351]

- Linus Torvalds (1969–): Finnish software engineer, creator of the Linux kernel.[352]

- Alan Turing (1912–1954): English mathematician, computer scientist, and theoretical biologist who provided a formalization of the concepts of algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, which can be considered a model of a general-purpose computer.[353]

- Matthew Turner (died ca. 1789): chemist, surgeon, teacher and radical theologian, author of the first published work of avowed atheism in Britain (1782).[354][355]

U

[edit]- Harold Urey (1893–1981): American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934. He played a significant role in the development of the atom bomb, but may be most prominent for his contribution to the study of the development of organic life from non-living matter.[356]

V

[edit]

- Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943): Russian and Soviet botanist and geneticist best known for having identified the centres of origin of cultivated plants. He devoted his life to the study and improvement of wheat, corn, and other cereal crops that sustain the global population.[357]

- J. Craig Venter (1946–): American biologist and entrepreneur, one of the first researchers to sequence the human genome, and in 2010 the first to create a cell with a synthetic genome.[358]

- Vladimir Vernadsky (1863–1945): Russian and Soviet mineralogist and geochemist who is considered one of the founders of geochemistry, biogeochemistry, and of radiogeology. His ideas of noosphere were an important contribution to Russian cosmism.[359]

- Carl Vogt (1817–1895): German scientist, philosopher and politician who emigrated to Switzerland. Vogt published a number of notable works on zoology, geology and physiology.[360]

W

[edit]

- W. Grey Walter (1910–1977): American neurophysiologist famous for his work on brain waves, and robotician.[361]

- James D. Watson (1928–): Molecular biologist, physiologist, zoologist, geneticist, Nobel-laureate, and co-discover of the structure of DNA.[362][363]

- John B. Watson (1878–1958): American psychologist who established the psychological school of behaviorism.[364][365][366]

- Steven Weinberg (1933–2021): American theoretical physicist. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979 for the unification of electromagnetism and the weak force into the electroweak force.[367][368][369]

- Victor Weisskopf (1908–2002): Austrian-American theoretical physicist, co-founder and board member of the Union of Concerned Scientists.[370]

- Frank Whittle (1907–1996): English aerospace engineer, inventor, aviator and Royal Air Force officer. He is credited with independently inventing the turbojet engine (some years earlier than Germany's Dr. Hans von Ohain) and is regarded by many as the father of jet propulsion.[371]

- Eugene Wigner (1902–1995): Hungarian-American theoretical physicist, engineer and mathematician. He received half of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his contributions to the theory of the atomic nucleus and the elementary particles, particularly through the discovery and application of fundamental symmetry principles".[372]

- Arnold Wolfendale (1927–2020): British astronomer who served as Astronomer Royal from 1991 to 1995, and was Emeritus Professor in the Department of Physics at Durham University.[373]

- Lewis Wolpert CBE FRS British FRSL (1929–2021): developmental biologist, author, and broadcaster.[374]

- Steve Wozniak (1950–): co-founder of Apple Computer and inventor of the Apple I and Apple II.[375]

- Elizur Wright (1804–1885): American mathematician and abolitionist, sometimes described as the "father of life insurance" for his pioneering work on actuarial tables.[376][377]

Z

[edit]

- Oscar Zariski (1899–1986): American mathematician and one of the most influential algebraic geometers of the 20th century.[378]

- Yakov Borisovich Zel'dovich (1914–1987): Soviet physicist born in Belarus. He played an important role in the development of Soviet nuclear and thermonuclear weapons, and made important contributions to the fields of adsorption and catalysis, shock waves, nuclear physics, particle physics, astrophysics, physical cosmology, and general relativity.[379][380]

- Emile Zuckerkandl (1922–2013): Austrian-born biologist who is considered one of the founders of the field of molecular evolution, who co-introduced the concept of the "molecular clock", which enabled the neutral theory of molecular evolution.[381]

- Konrad Zuse (1910–1995): German civil engineer, inventor and computer pioneer. His greatest achievement was the world's first programmable computer; the functional program-controlled Turing-complete Z3 became operational in May 1941. He is regarded as one of the inventors of the modern computer.[382][383]

- Fritz Zwicky (1898–1974): Swiss astronomer and astrophysicist.[384][385]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ Aaronson, Scott. "Scott Aaronson". Archived from the original on September 13, 2023. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

I'm Schlumberger Centennial Chair of Computer Science at The University of Texas at Austin, and director of its Quantum Information Center.

- ^ Scott Aaronson (January 16, 2007). "Long-awaited God post". Shtetl-Optimized – The Blog of Scott Aaronson. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

If you'd asked, I would've told you that I, like yourself, am what most people would call a disbelieving atheist infidel heretic.

- ^ Joseph McCabe (1945). A Biographical Dictionary of Ancient, Medieval, and Modern Freethinkers. Haldeman-Julius Publications. Retrieved 7 April 2013.

He was not only a distinguished German physicist and one of the most famous inventors on the staff at the Zeiss optical works at Jena but a notable social reformer, By a generous scheme of profit-sharing he virtually handed over the great Zeiss enterprise to the workers. Abbe was an intimate friend of Haeckel and shared his atheism (or Monism). Leonard Abbot says in his life of Ferrer that Abbe had "just the same ideas and aims as Ferrer."

- ^ Ajzenberg-Selove, Fay. A Matter of Choices: Memoirs of a Female Physicist. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1994. Print. "I explained carefully to Louis that I was a Jew and an atheist..."

- ^ Jonathan Israel (2011). Democratic Enlightenment: Philosophy, Revolution, and Human Rights 1750–1790. Oxford University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-19-954820-0.

D'Alembert, though privately an atheist and materialist, presented the respectable public face of 'la philosophie' in the French capital while remaining henceforth uninterruptedly aligned with Voltaire.

- ^ James E. Force; Richard Henry Popkin (1990). James E. Force; Richard Henry Popkin (eds.). Essays on the Context, Nature, and Influence of Isaac Newton's Theology. Springer. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-7923-0583-5.

Unlike the French and English deists, and unlike the scientific atheists such as Diderot, d'Alembert, and d'Holbach,...

- ^ Willem B. Drees (1990). Beyond the Big Bang: Quantum Cosmologies and God. Open Court Publishing. pp. 22–24. ISBN 978-0-8126-9118-4.

- ^ "Sometime after this, Hannes Alfvén was brought to the presence of Prime Minister Ben-Gurion. The latter was curious about this young Swedish scientist who was being much talked about. After a good chat, Ben Gurion came right to the point: "Do you believe in God?" Now, Hannes Alfvén was not quite prepared for this. So he considered his answer for a few brief seconds. But Ben-Gurion took his silence to be a "No." So he said: "Better scientist than you believes in God."" As told by Hannes Alfvén to Asoka Mendis, Hannes Alfvén Birth Centennial Archived 2018-10-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Nuclear power is uniquely unforgiving: as Swedish Nobel physicist Hannes Alfvén said, "No acts of God can be permitted."" Amory Lovins, Inside NOVA – Nuclear After Japan: Amory Lovins, pbs.org.

- ^ "Alfven dismissed in his address religion as a "myth," and passionately criticized the big-bang theory for being dogmatic and violating basic standards of science, to be no less mythical than religion." Helge Kragh, Matter and Spirit in the Universe: Scientific and Religious Preludes to Modern Cosmology (2004), page 252.

- ^ "I find it more comfortable to say I'm an atheist, and for that I probably have someone like Dawkins to thank." – Jim Al-Khalili, BBC – Radio 4 – Science Explorer: Jim Al-Khalili featured in The Life Scientific, BBC.co.uk.com.

- ^ Philip W. Anderson (2011). "Imaginary Friend, Who Art in Heaven". More and Different: Notes from a Thoughtful Curmudgeon. World Scientific. p. 177. ISBN 978-981-4350-12-9.

We atheists can, as he does, argue that, with the modern revolution in attitudes toward homosexuals, we have become the only group that may not reveal itself in normal social discourse.

- ^ "Jacob Appelbaum (Part 1/2) Digital Anti-Repression Workshop – April 26, 2012". YouTube. Retrieved 28 June 2013.

Like, for me, as an atheist, bisexual, Jew, I'm gonna go on, uh – oh and Emma Goldman is one of my great heroes and I really think that anarchism is a fantastic principle by which to fashion a utopian society even if we can't get there.

- ^ "The same Arago who spent his time criticizing unfounded myths now peddled them. Arago the atheist now spoke of souls." Theresa Levitt, The shadow of enlightenment: optical and political transparency in France, 1789–1848, page 105.

- ^ Gordon Stein (1988). The encyclopedia of unbelief. Vol. 1. Prometheus Books. p. 594. ISBN 978-0-87975-307-8.

Svante Arrhenius (I859-I927), recipient of the Nobel Prize in chemistry (I903), was a declared atheist and the author of The Evolution of the Worlds and other works on cosmic physics.

- ^ "'He brings a humanness to (science) that's very refreshing'". Rediff On The News. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

Although he is an atheist, Dr Ashtekar says, his attitude toward work is from the Hindu religious text, the Bhagavad Gita.

- ^ Asprey, Margaret Williams (2014). A True Nuclear Family. Bloomington, Indiana: Trafford. pp. 110, 349. ISBN 9781490726656. OCLC 870564799.

- ^ When asked by Rod Liddle in the documentary The Trouble with Atheism "Give me your views on the existence, or otherwise, of God", Peter Atkins replied "Well it's fairly straightforward: there isn't one. And there's no evidence for one, no reason to believe that there is one, and so I don't believe that there is one. And I think that it is rather foolish that people do think that there is one.""The Trouble with Atheism, UK Channel 4 TV". 2006-12-18.

- ^ "Scott Atran: Scientists and the secular-minded predict the demise of religion, but around the globe it is thriving". TheGuardian.com. 28 October 2008.

- ^ "Although he became an atheist early in life and resented the strict upbringing of his parents' religion, he identified with Jewish culture and joined several international fights against anti-Semitism." Craver, Carl F: "Axelrod, Julius", Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography Vol. 19 p. 122. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008.

- ^ "In religious matters he was an atheist." A.G. MacGregor: "Bailey, Edward Battersby", Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography Vol. 1 p. 393. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008.

- ^ Noel G. Charlton (2008). Understanding Gregory Bateson: mind, beauty, and the sacred earth. SUNY Press. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-7914-7452-5.

This was to be the last large-scale work of lifelong atheist Bateson, seeking to understand the meaning of the sacred.

- ^ "A confirmed agnostic, he [Bateson] was converted to atheism after attending a dinner where he tried to converse with a woman who was a creationist. "For many years what had been good enough for Darwin was good enough for me. Not long after that dreadful dinner, Richard Dawkins wrote to me to ask whether I would publicly affirm my atheism. I could see no reason why not." " Lewis Smith, 'Science has second thoughts about life', The Times (London), January 1, 2008, Pg. 24.

- ^ "William Bateson was a very militant atheist and a very bitter man, I fancy. Knowing that I was interested in biology, they invited me when I was still a school girl to go down and see the experimental garden. I remarked to him what I thought then, and still think, that doing research must be the most wonderful thing in the world and he snapped at me that it wasn't wonderful at all, it was tedious, disheartening, annoying and anyhow you didn't need an experimental garden to do research." Interview with Dr. Cecilia Gaposchkin Archived 2015-05-03 at the Wayback Machine by Owen Gingerich, March 5, 1968.

- ^ George Beadle, An Uncommon Farmer: The Emergence of Genetics in the 20th Century. CSHL Press. 2003. p. 273. ISBN 9780879696887. Beadle's views on this occasion were somewhat more tempered than David's characterization of him as a "vehement atheist," and from his earliest days "intolerant of religion and other forms of superstition.

- ^ John Ellis, D. Amati (2000). "Biographical notes on John Bell". Quantum Reflections. Cambridge University Press. p. xi. ISBN 978-0-521-63008-5. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

By now, he was also a 'Protestant Atheist', which he remained all his life.

- ^ Andrew Whitaker; Mary Bell; Shan Gao (Sep 19, 2016). "1 – John Bell – The Irish Connection". Quantum Nonlocality and Reality: 50 Years of Bell's Theorem. Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-107-10434-1.

John Bell was certainly not interested in Protestantism as such – his wife Mary [33] has reported that he was an atheist most of his life.

- ^ Richard Bellman (June 1984). "Growing Up in New York City". Eye Of The Hurricane. World Scientific Publishing Company. p. 7. ISBN 978-981-4635-70-7. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

Naturally, I was raised as an atheist. This was quite easy since the only one in the family that had any religion was my grandmother, and she was of German stock. Although she believed in God, and went to the synagogue on the high holy days, there was no nonsense about ritual. I well remember when I went off to the army, she said, "God will protect you." I smiled politely. She added, "I know you don't believe in God, but he will protect you anyway." I know many sophisticated and highly intelligent people who are practicing Catholics, Protestants, Jews, Mormons, Hindus, Buddhists, etc., feel strongly that religion, or lack of it, is a highly personal matter. My own attitude is like Lagrange's. One day, he was asked by Napoleon whether he believed in God. "Sire," he said, "I have no need of that hypothesis."

- ^ "I am so sorry to hear of Asher's passing. I will miss his scientific insight and advice, but even more his humor and stuborn [sic] integrity. I remember when one of his colleagues complained about Asher's always rejecting his manuscript when they were sent to him to referee. Asher said in effect, "You should thank me. I am only trying to protect your reputation." He often pretended to consult me, a fellow atheist, on matters of religious protocol. As we waited in line to eat the hors d'oeuvres at a conference in Evanston, he said, "There is a prayer Jews traditionally say when they do something new that they have never done before. I am about to eat a new kind of non-Kosher food. Do you think I should say the prayer?" My wife and grown children, who are visiting us this new year, and remember Asher from when we all lived in Cambridge 20 years ago, join me in sending you our condolences for this sudden loss of an irrepressible and irreplaceable person. Please convey our feelings especially to your mother at this difficult time. " Charles H. Bennett's letter written to the family of Israeli physicist, Asher Peres, A selection of the many letters of condolence sent to the Peres family during January 2005 Archived 2011-11-26 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "The Bernals were originally Sephardic Jews who came to Ireland in 1840 from Spain via Amsterdam and London. They converted to Catholicism and John was Jesuit-educated. John enthusiastically supported the Easter Rising and, as a boy, he organised a Society for Perpetual Adoration. He moved away from religion as an adult, becoming an atheist." William Reville, John Desmond Bernal – The Sage Archived 2014-10-25 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Döpfner, Mathias. "The inventor of the web Tim Berners-Lee on the future of the internet, 'fake news,' and why net neutrality is so important". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ Robert K. Wilcox (2010). The Truth About the Shroud of Turin: Solving the Mystery. Regnery Gateway. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-59698-600-8.

In 1902, Marcellin P. Berthelot, often called the founder of modern organic chemistry, was one of France's most celebrated scientists—if not the world's. He was permanent secretary of the French Academy, having succeeded the giant Louis Pasteur, the renowned microbiologist. Unlike Delage, an agnostic, Berthelot was an atheist—and militantly so.

- ^ Thomas de Wesselow (2012). The Sign: The Shroud of Turin and the Secret of the Resurrection. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-101-58855-0.

Although Delage made it clear that he did not regard Jesus as the resurrected Son of God, his paper upset the atheist members of the Academy, including its secretary, Marcellin Berthelot, who prevented its full publication in the Academy's bulletin.

- ^ a b "Napoleon replies: "How comes it, then, that Laplace was an atheist? At the Institute neither he nor Monge, nor Berthollet, nor Lagrange believed in God. But they did not like to say so." Baron Gaspard Gourgaud, Talks of Napoleon at St. Helena with General Baron Gourgaud (1904), page 274.

- ^ Horgan, J. (1992) Profile: Hans A. Bethe – Illuminator of the Stars, Scientific American 267(4), 32–40.

- ^ Denis Brian (2001). The Voice Of Genius: Conversations With Nobel Scientists And Other Luminaries. Basic Books. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7382-0447-5.

Bethe: "I am an atheist."

- ^ Larry Hannant (1998). The Politics of Passion: Norman Bethune's Writing and Art. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-0907-4.

Bethune was a communist and an atheist with a healthy contempt for his evangelical father.

- ^ "The grandson of a vicar on his father's side, Blackett respected religious observances that were established social customs, but described himself as agnostic or atheist." Mary Jo Nye: "Blackett, Patrick Maynard Stuart." Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. 19 p. 293. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons, 2008.

- ^ Clarke, Peter. All in the Mind?: Does Neuroscience Challenge Faith? N.p.: Lion, 2015. Print. "Blakemore is indeed an atheist..."

- ^ Tom Siegfried (June 28, 2013). "When the atom went quantum – Bohr's revolutionary atomic theory turns 100". Society for Science & the Public 2000. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

As for standard religion, though, Bohr was unsympathetic. His mother was a nonpracticing Jew, his father an atheist Lutheran.

- ^ Simmons, John (1996). The Scientific 100: a rankings of the most influential scientists, past and present. Carol Publishing Group. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-8065-1749-0.

His mother was warm and intelligent, and his father, as Bohr himself later recalled, recognized "that something was expected of me." The family was not at all devout, and Bohr became an atheist who regarded religious thought as harmful and misguided.

- ^ J. Faye; H. Folse, eds. (2010). Niels Bohr and Contemporary Philosophy. Springer. p. 88. ISBN 978-90-481-4299-6.

Planck was religious and had a firm belief in God; Bohr was not, but his objection to Planck's view had no anti-religious motive.

- ^ Ray Spangenburg; Diane Kit Moser (2008). Niels Bohr: Atomic Theorist (2 ed.). Infobase Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8160-6178-5.

Niels had quietly resigned his membership in the Lutheran Church the previous April. Although he had sought out religion as a child, by the time of their marriage he no longer "was taken" by it, as he put it. "And for me it was exactly the same," Margrethe later explained. "[Interest in religion] disappeared completely," although at the time of their wedding, she was still a member of the Lutheran Church. (Niels's parents were also married in a civil, not a religious, ceremony, and Harald also resigned his membership in the Lutheran Church just before his wedding, a few years later.)

- ^ Science and Religion in Dialogue, Two Volume Set. John Wiley & Sons. 11 January 2010. p. 416. ISBN 978-1-4051-8921-7.

On the other hand Bohr wrote of his admiration for the writing and presentation of Kierkegaard – at the same time stating he could not accept some of it. Part of this may have followed from Kierkegaard being a very avowed, yet rather circuitous proponent of a costly Christian faith, while after a youth of confirming faith Bohr himself was a non-believer.