Presidency of Abraham Lincoln

| |

| Presidency of Abraham Lincoln March 4, 1861 – April 15, 1865 (Assassination) | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Republican (1861–1864) National Union (1864–1865) |

| Election | |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

| Library website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal Political 16th President of the United States First term Second term Presidential elections Speeches and works

Assassination and legacy  |

||

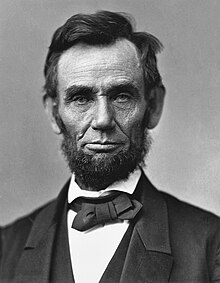

The presidency of Abraham Lincoln began March 4, 1861, when Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as the 16th president of the United States, and ended upon his death on April 15, 1865, 42 days into his second term. Lincoln was the first member of the recently established Republican Party elected to the presidency. Lincoln successfully presided over the Union victory in the American Civil War, which dominated his presidency and resulted in the end of slavery. He was succeeded by Vice President Andrew Johnson.

Lincoln took office following the 1860 presidential election, in which he won a plurality of the popular vote in a four-candidate field. Almost all of Lincoln's votes came from the Northern United States, as the Republicans held little appeal to voters in the Southern United States. A former Whig, Lincoln ran on a political platform opposed to the expansion of slavery in the territories. His election served as the immediate impetus for the outbreak of the Civil War. After being sworn in as president, Lincoln refused to accept any resolution that would result in Southern secession from the Union. The Civil War began weeks into Lincoln's presidency with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, a federal installation located within the boundaries of the Confederacy.

Lincoln was called on to handle both the political and military aspects of the Civil War, facing challenges in both spheres. As commander-in-chief, he ordered the suspension of the constitutionally-protected right to habeas corpus in the state of Maryland in order to suppress Confederate sympathizers. He also became the first president to institute a military draft. As the Union faced several early defeats in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War, Lincoln cycled through numerous military commanders during the war, finally settling on General Ulysses S. Grant, who had led the Union to several victories in the Western Theater. Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation recognized the legal freedom of the 3.5 million slaves then held in Confederate territory and established emancipation as a Union war goal. In 1865, Lincoln was instrumental in the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, which made slavery unconstitutional. Lincoln also presided over the passage of important domestic legislation, including the first of the Homestead Acts, the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862, and the Pacific Railroad Act of 1862. He ran for re-election in 1864 on the National Union ticket, which was supported by War Democrats in addition to Republicans. Though Lincoln feared he might lose the contest, he defeated his former subordinate, General George B. McClellan of the Democratic Party, in a landslide. Months after the election, Grant would essentially end the war by defeating the Confederate army led by General Robert E. Lee. Lincoln's assassination in April 1865, five days after the surrender of Lee, left the final challenge of reconstructing the nation to others.

Following his death, Lincoln was portrayed as the liberator of the slaves, the savior of the Union, and a martyr for the cause of freedom. Political historians have long held Lincoln in high regard for his accomplishments and personal characteristics. Alongside George Washington and Franklin D. Roosevelt, he has been consistently ranked both by scholars and the public as one of the top three greatest American presidents, often as the greatest president in American history.

Election of 1860

[edit]

Lincoln, who was a former Whig congressman, emerged as a major Republican presidential candidate following his narrow loss to Democrat Stephen A. Douglas in the 1858 Senate election in Illinois.[1] Though he lacked the broad support that Republican Senator William H. Seward of New York had, Lincoln believed that he could emerge as the Republican presidential nominee at the convention after multiple ballots. Lincoln spent much of 1859 and 1860 building support for his candidacy, and his Cooper Union speech was well received by eastern elites. Lincoln positioned himself in the "moderate center" of his party; he opposed the expansion of slavery into the territories but accepted the consensus that the federal government could not abolish slavery in the slave states.[2] On the first ballot of the May 1860 Republican National Convention, Lincoln finished second to Seward, but Seward was unable to clinch the nomination. Ignoring Lincoln's strong dictate to "make no contracts that bind me",[3] his managers maneuvered to win Lincoln's nomination on the third ballot of the convention. Delegates then nominated Senator Hannibal Hamlin from Maine for vice president.[4] The party platform opposed the extension of slavery into the territories but pledged not to interfere with it in the states. It also endorsed a protective tariff, internal improvements such as a transcontinental railroad, and policies designed to encourage the settlement of public land in the West.[5][6]

The 1860 Democratic National Convention met in April 1860, but adjourned after failing to agree on a candidate. A second convention met in June and nominated Stephen Douglas as the presidential nominee, but several pro-slavery Southern delegations refused to support Douglas, as they demanded a strongly pro-slavery nominee. These Southern Democrats held a separate convention that nominated incumbent Vice President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky for president. A group of former Whigs and Know Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party and nominated John Bell for president. Breckinridge and Bell would primarily contest the South, while Lincoln and Douglas would compete for votes in the North. Republicans were confident after these party conventions, with Lincoln predicting that the fractured Democrats stood little chance of winning the election.[4]

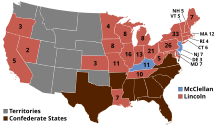

Lincoln carried all but one Northern state to win an Electoral College majority with 180 votes to 72 for Breckinridge, 39 for Bell, and 12 for Douglas. Lincoln won every county in New England and most of the remaining counties in the North, but he won just two of the 996 Southern counties.[7] Nationwide, Lincoln took 39.8 percent of the popular vote, while Douglas won 29.5 percent of the popular vote, Breckenridge won 18.1 percent, and Bell won 12.6 percent.[8] 82.2 percent of eligible voters took part in the contentious election, the second highest turnout in U.S. history. Despite Republican success in the presidential election, the party failed to win a majority in either house of Congress,[9] although after the Southern states seceded, Lincoln governed with a majority in both houses.

Transition period

[edit]Threat of secession

[edit]Following Lincoln's victory, all the slave states began to consider secession. Lincoln was not scheduled to take office until March 4, 1861, leaving incumbent Democratic President James Buchanan, a "doughface" from Pennsylvania who had been sympathetic to the South, to preside over the country until that time.[10] President Buchanan declared that secession was illegal but denied that the government had any power to resist it. Lincoln had no official power to act while the secession crisis escalated.[11] Nevertheless, Lincoln was barraged with advice. Many wanted him to provide reassurances to the South that its interests were not being threatened.[12] Realizing that soothing words on the rights of slaveholders would alienate the Republican base, while taking a strong stand on the indestructibility of the Union would further inflame Southerners, Lincoln chose a policy of silence. He believed that, given enough time without any overt acts or threats to the South, Southern unionists would carry the day and bring their states back into the Union.[13] At the suggestion of a Southern merchant who contacted him, Lincoln did make an indirect appeal to the South by providing material for Senator Lyman Trumbull to insert into his own public address. Republicans praised Trumbull's address, Democrats assailed it, and the South largely ignored it.[14]

In December 1860, both the House and Senate formed special committees to address the unfolding crisis. Lincoln communicated with various Congressmen that there was room for negotiation on issues such as fugitive slaves, slavery in the District of Columbia, and the domestic slave trade. However he made it clear that he was unalterably opposed to anything which would allow the expansion of slavery into any new states or territories.[15] On December 6, Lincoln wrote to Congressman Orlando Kellogg, a Republican on the special House committee, saying that Kellogg should "entertain no proposition for a compromise in regard to the extension of slavery. The instant you do, they have us under again; all our labor is lost, and sooner or later must be done over. Douglas is sure to be again trying to bring in his [popular sovereignty]. Have none of it. The tug has to come & better now than later."[16]

In mid-December, Senator John J. Crittenden of Kentucky, the chairman of the special Senate committee, proposed a package of six constitutional amendments, known as the Crittenden Compromise. The compromise would protect slavery in federal territories south of the 36°30′ parallel and prohibit it in territories north of that latitude, with newly admitted states deciding on the status of slavery within their borders. Congress would be forbidden from abolishing slavery in any state (or the District of Columbia) or interfering with the domestic slave trade. Despite pressure from Seward, Lincoln refused to support the compromise.[17] Still opposed to the expansion of slavery into the territories, Lincoln privately asked Republican Senators to oppose the compromise, and it failed to pass Congress.[10]

Deepening crisis

[edit]

Lincoln believed that Southern threats of secession were mostly bluster and that the sectional crisis would be defused, as it had in 1820 and 1850.[18] However, many Southerners were convinced that assenting to Lincoln's presidency and the restriction of slavery in the territories would ultimately lead to the extinction of slavery in the United States.[19] On December 20, 1860, South Carolina voted to secede, and six other Southern states seceded in the next forty days. In February, these Southern states formed the Confederate States of America (CSA) and elected Jefferson Davis as provisional president. Despite the formation of the CSA, the slave-holding states of Arkansas, North Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri still remained part of the union.[18]

In February 1861, two final political efforts were made to preserve the Union. The first was made by a group of 131 delegates sent by 21 states to a Peace Conference, held at the Willard's Hotel in the nation's capital.[20] The convention submitted to Congress a seven-point constitutional amendment proposal similar in content to the earlier Crittenden Compromise. The proposal was rejected by the Senate and never considered by the House.[21][22] The second effort was a "never-never" constitutional amendment on slavery, that would shield domestic institutions of the states from Congressional interference and from future constitutional amendments. Commonly known as the Corwin Amendment, the measure was approved by Congress, but was not ratified by the state legislatures.[23]

Arrival in Washington, D.C.

[edit]On February 11, 1861, Lincoln boarded a special train that over the course of the next two weeks would take him to the nation's capital.[24] Lincoln spoke several times each day during the train trip. While his speeches were mostly extemporaneous, his message was consistent: he had no hostile intentions towards the South, disunion was not acceptable, and he intended to enforce the laws and protect property.[25]

Rumors abounded during the course of the trip of various plots to kill Lincoln. Samuel Felton, president of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad, hired detective Allan Pinkerton to investigate reports that secessionists might try to sabotage the railroad along the route. In conducting his investigation Pinkerton obtained information that indicated to him that an attempt on Lincoln's life would be made in Baltimore.[26] As a result of the threat, the travel schedule was altered, tracks were closed to other traffic, and the telegraph wires even cut to heighten security. Lincoln and his entourage passed through Baltimore's waterfront at around 3 o'clock in the early morning of February 23, and arrived safely in the nation's capital a few hours later. The unannounced departure from the published schedule, along with the unconventional attire Lincoln wore to keep a low profile, led to critics and cartoonists accusing him of sneaking into Washington in disguise.[27] Lincoln met with Buchanan and Congressional leaders shortly after arriving in Washington. He also worked to complete his cabinet, meeting with Republican Senators to obtain their feedback.[28]

First inauguration

[edit]Lincoln, aware that his inaugural address would be delivered in an atmosphere filled with fear and anxiety, and amid an unstable political landscape, sought guidance from colleagues and friends as he prepared it. Among those whose counsel Lincoln sought was Orville Browning, who advised Lincoln to omit the phrase "to reclaim the public property and places which have fallen". He also asked his former rival (and Secretary of State-designate) William Seward to review it. Seward exercised his due diligence by presenting Lincoln with a six-page analysis of the speech in which he offered some 49 suggested changes, of which the president-elect incorporated 27 into the final draft.[30]

Lincoln's first presidential inauguration occurred on March 4, 1861, on the East Portico of the United States Capitol.[31] Prior to taking the oath, Lincoln delivered his inaugural address. He opened by attempting to reassure the South that he had no intention or constitutional authority to interfere with slavery in states where it already existed. He promised to enforce the fugitive slave law and spoke favorably about a pending constitutional amendment that would preserve slavery in the states where it currently existed. He also assured the states that had already seceded that the federal government would not "assail" (violently attack) them.[32][33] After these assurances, however, Lincoln declared that secession was "the essence of anarchy" and it was his duty to "hold, occupy, and possess the property belonging to the government".[34] Focusing on those within the South who were still on the fence regarding secession, Lincoln contrasted "persons in one section or another who seek to destroy the Union as it exists" versus "those, however, who really love the Union."[35] In his closing remarks Lincoln spoke directly to the secessionists, and asserted that no state could secede from the Union "upon its own mere motion" and emphasized the moral commitment that he was undertaking to "preserve, protect, and defend" the laws of the land.[36] He then concluded the address with a firm but conciliatory message:

We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearth-stone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.[37]

Administration

[edit]

| The Lincoln cabinet[38] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | Abraham Lincoln | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of State | William H. Seward | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Treasury | Salmon P. Chase | 1861–1864 |

| William P. Fessenden | 1864–1865 | |

| Hugh McCulloch | 1865 | |

| Secretary of War | Simon Cameron | 1861–1862 |

| Edwin Stanton | 1862–1865 | |

| Attorney General | Edward Bates | 1861–1864 |

| James Speed | 1864–1865 | |

| Postmaster General | Montgomery Blair | 1861–1864 |

| William Dennison Jr. | 1864–1865 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | Gideon Welles | 1861–1865 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Caleb B. Smith | 1861–1862 |

| John Palmer Usher | 1863–1865 | |

Lincoln began the process of constructing his cabinet on election night.[39] In an effort to create a cabinet that would unite the Republican Party, Lincoln attempted to reach out to every faction of his party, with a special emphasis on balancing former Whigs with former Democrats.[40] Lincoln's eventual cabinet would include all of his main rivals for the Republican nomination. He did not shy away from surrounding himself with strong-minded men, even those whose credentials for office appeared to be much more impressive than his own.[41] Though the cabinet appointees held different views on economic issues, all opposed the extension of slavery into the territories.[42]

The first cabinet position filled was that of Secretary of State. It was tradition for the president-elect to offer this, the most senior cabinet post, to the leading (best-known and most popular) person of his political party. William Seward was that man and in mid-December 1860, Vice President-elect Hamlin, acting on Lincoln's behalf, offered the position to him.[43] Seward had been deeply disappointed by his failure to win the 1860 Republican presidential nomination, but he agreed to serve as Lincoln's Secretary of State.[44] By the end of 1862, Seward had emerged as the dominant figure in Lincoln's cabinet, though the Secretary of State's conservative policies on abolition and other issues alienated many within the Republican Party. Despite pressure from some congressional leaders to fire Seward, Lincoln retained his Secretary of State for the duration of his presidency.[45]

Lincoln's choice for Secretary of the Treasury was Ohio Senator Salmon P. Chase, Seward's chief political rival.[46] Chase was the leader of the more radical faction of Republicans that sought to abolish slavery as quickly as possible.[47] Seward, among others, opposed the selection of Chase because of both his strong antislavery record and his opposition to any type of settlement with the South that could be considered an appeasement of slaveholders.[48] Chase surreptitiously sought the 1864 Republican nomination, and he frequently worked to undermine Lincoln's re-election, but Lincoln nonetheless retained Chase due to Chase's competence as Secretary of the Treasury and popularity among Radical Republicans.[49] Chase offered his resignation in June 1864 due to a dispute over an appointment, and Lincoln, having just been renominated for president, accepted Chase's resignation. Lincoln replaced Chase with William P. Fessenden, a Radical Republican who had served as Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee.[50] The aging Fessenden resigned in February 1865 and was replaced with Hugh McCulloch, who had served as the Comptroller of the Currency.[51]

The most problematic cabinet selection made by Lincoln was that of Simon Cameron as the Secretary of War. Cameron was one of the most influential public leaders in the crucial political state of Pennsylvania, but he was also alleged to be one of the most corrupt.[52] He was opposed within his own state by the faction led by Governor-elect Andrew G. Curtin and party chairman A. K. McClure. Nonetheless, by Inauguration Day the competing factions realized that it was important to business interests that at least some Pennsylvanian be in Lincoln's cabinet, and Cameron was made Secretary of War.[53] Historian William Gienapp believed that the final selection of Cameron for this soon-to-be-critical position was a clear indicator that Lincoln did not anticipate a civil war.[54] Feeling that Cameron was not capable of handling the War Department, Lincoln tactfully removed Cameron in January 1862 by appointing him as the ambassador to Russia.[55] Cameron was replaced by Edwin Stanton, a staunchly Unionist pro-business conservative Democrat who moved toward the Radical Republican faction. Stanton worked more often and more closely with Lincoln than any other senior official.[56]

Lincoln appointed two individuals from the border states to his cabinet. Montgomery Blair of Maryland, who was popular among anti-slavery and border state Democrats, became Lincoln's first Postmaster-General. Blair came from a prominent political family, as his father, Francis Preston Blair, had served as an adviser to President Andrew Jackson, while his younger brother, Francis Preston Blair Jr., was a major Unionist leader in Missouri.[57] Blair's Postal Service aptly responded to the challenges posed by the Civil War, but the Blair family alienated key Northern and border state leaders during the war. Seeing Blair as a political liability, Lincoln dismissed Blair from the cabinet in September 1864, replacing him with William Dennison.[58] Missouri provided the other border state cabinet member in the form of Attorney General Edward Bates.[59] Bates resigned in 1864, and was replaced by James Speed, the older brother of Lincoln's close friend, Joshua Fry Speed.[60]

Lincoln tasked Vice President-elect Hamlin with finding someone from a New England state for the cabinet. Hamlin recommended Gideon Welles of Connecticut, a former Democrat who had served in the Navy Department under President James K. Polk. Other influential Republicans concurred, and Welles became Secretary of the Navy.[61] For the position of Interior Secretary, Lincoln chose Caleb Blood Smith of Indiana, a former Whig representing the same type of Midwestern constituency as Lincoln. His critics faulted him for some of his railroad ventures, accused him of being a Doughface, and questioned his intellectual capacity for a high government position. In the end, Smith's selection for Secretary of the Interior had much to do with his campaign efforts on behalf of Lincoln and their friendship.[62] Smith would serve less than two years before resigning due to poor health.[63] He was replaced by John Palmer Usher.[63]

Judicial appointments

[edit]Southern Democrats had dominated the Supreme Court of the United States in the period before Lincoln took office, and their unpopular ruling in the 1857 case of Dred Scott v. Sandford had done much to invigorate the Republican cause in the North.[64] When Lincoln took office, the death of Peter Vivian Daniel had left a vacant seat on the Supreme Court. Two more vacancies arose in early 1861 due to the death of John McLean and the resignation of John Archibald Campbell. Despite the vacancies, Lincoln did not nominate a replacement for any of the justices until January 1862. Noah Haynes Swayne, Samuel Freeman Miller, and David Davis were all nominated by Lincoln and confirmed by the Senate in 1862. Congress added a tenth seat on the Court through the passage of the Tenth Circuit Act of 1863, and Lincoln appointed a War Democrat, Stephen Johnson Field, to fill that seat. After Roger Taney died in 1864, Lincoln appointed former Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase to the position of Chief Justice. Lincoln's appointments gave Northern Unionists a majority on the Court.[65] Lincoln also appointed 27 judges to the United States district courts during his time in office.[66]

American Civil War

[edit]Fort Sumter

[edit]

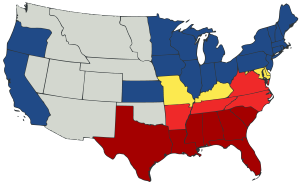

Legend:

By the time Lincoln assumed office seven states had declared their secession and had seized federal property within their bounds, but the United States retained control of major military installations at Fort Sumter near Charleston and Fort Pickens near Pensacola.[67] Less secure than Fort Pickens, and situated in the secessionist hotbed of South Carolina, Fort Sumter emerged as an important symbolic issue in both the North and South during early 1861.[68] Any hope Lincoln might have had about using time to his advantage in addressing the crisis was shattered on his first full day in office, when he read a letter from Major Robert Anderson, the commander at Fort Sumter, stating that his troops would run out of provisions within four to six weeks.[67]

At a meeting on March 7, General Winfield Scott, the top-ranking general in the army, and John G. Totten, the army's chief engineer, said that simply reinforcing the fort was not possible, although Secretary of the Navy Welles disagreed. Scott advised Lincoln that it would take a large fleet, 25,000 troops, and several months of training in order to defend the fort. On March 13, Postmaster General Blair, the strongest proponent in the cabinet for standing firm at Fort Sumter, introduced Lincoln to his brother-in-law, Gustavus V. Fox. Fox presented a plan for a naval resupply and reinforcement of the fort. The plan had been approved by Scott during the last month of the previous administration, but Buchanan had rejected it.[70] On March 15, Lincoln asked each cabinet member to provide a written answer to the question, "Assuming it to be possible to now provision Fort-Sumter, under all circumstances, is it wise to attempt it?" Only Blair gave his unconditional approval to the plan. No decision was reached, but Lincoln personally dispatched Fox, Stephen A. Hurlbut, and Ward Lamon to South Carolina to assess the situation. The recommendations that came back were that reinforcement was both necessary, since secessionist feeling ran high and threatened the fort, and feasible, despite Anderson's misgivings.[71]

On March 28, Scott recommended that both Pickens and Sumter be abandoned, basing his decision more on political than military grounds. The next day a deeply agitated Lincoln presented Scott's proposal to the cabinet. Blair was now joined by Welles and Chase in supporting reinforcement. Bates was non-committal, Cameron was not in attendance, and Seward and Smith opposed resupply. Later that day Lincoln gave Fox the order to begin assembling a squadron to reinforce Fort Sumter.[72] Lincoln's policy of re-supplying Fort Sumter and Fort Pickens was designed to deny the right of secession without resorting to violence, which he hoped would allow the administration maintain support among both Northerners and Southern Unionists.[73]

With the Fort Sumter mission ready to go, Lincoln sent State Department clerk Robert S. Chew to inform South Carolina Governor Francis W. Pickens of the impending re-supply of the fort.[74] The message was delivered to Governor Pickens on April 8.[75] The information was telegraphed that night to Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Richmond. The Confederate cabinet was already meeting to discuss the Sumter crisis, and on April 10 Davis decided to demand the surrender of the fort and bombard it if the demand was refused.[76] An attack on the fort was initiated on April 12, and the fort surrendered the next day. The relief expedition sent by the Union arrived too late to intervene.[77]

Early war

[edit]On April 15, following the Battle of Fort Sumter, Lincoln declared that a state of rebellion existed and called up a force of seventy-five thousand state militiamen to serve three-month terms. While Northern states rallied to the request, border states such as Missouri refused to provide soldiers. Lincoln also called Congress into a special session to begin in July. Though an in-session Congress could potentially affect his freedom of action, Lincoln needed Congress to authorize funds to fight the war. On the advice of Winfield Scott, Lincoln asked a political ally to offer General Robert E. Lee command of the Union forces, but Lee chose to serve the Confederacy. Union soldiers in Southern states burned federal facilities to prevent Southern forces from taking control of them, while Confederate sympathizers rioted in Baltimore. To ensure the security of the capital, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus in Maryland and ignored a court order to release John Merryman from prison. While Lincoln struggled to maintain order in Maryland and other border states, Virginia, North Carolina, Arkansas, and Tennessee all seceded from the Union. North Carolina was the last state to secede, doing so on May 20.[78]

With the secession of several states, Lincoln's Republicans enjoyed large majorities in both houses of Congress. War Democrats such as Andrew Johnson of Tennessee also supported many of Lincoln's policies, though Copperheads (Peace Democrats) advocated peace with the Confederacy.[79] From the start, it was clear that bipartisan support would be essential to success in the war effort, and any action, such as the appointment of generals, could alienate factions on both sides of the aisle.[80] Lincoln appointed several political generals to curry favor with various groups, especially Democrats.[81] On its return in July 1861, Congress supported Lincoln's war proposals, providing appropriations for the expansion of the army to 500,000 men.[82] Organizing the army would prove to be a challenge for Lincoln and the War Department, as many professional officers resisted civilian control, while many state militias sought to act autonomously. Knowing that success in the war required the support of local officials in mobilizing soldiers, Lincoln used patronage powers and personal diplomacy to ensure that Northern leaders remained devoted to the war effort.[83][84]

Having succeeded in rallying the North against secession, Lincoln next determined to attack the Confederate capital of Richmond, which was located just one hundred miles from Washington. Lincoln was disappointed by the state of the War Department and Navy Department, and Scott counseled that the army needed more time to train, but Lincoln nonetheless ordered an offensive. As the aged Scott was unable to lead the army himself, General Irvin McDowell led a force of 30,000 men south, where he met a force led by Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard. At the First Battle of Bull Run, the Confederate army dealt the Union a major defeat, ending any hope of a quick end to the war.[85]

Following the secession of four states after the Battle of Fort Sumter, one of Lincoln's major concerns was that the slave-holding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri would join the Confederacy. Of these four states, Lincoln was least concerned about Delaware, which had a proportionally large pro-Union population. Due to its location, Maryland remained a critical part of the Union. Lincoln continued to suppress Southern sympathizers in the state, but historian Ronald White also notes Lincoln's forbearance in refusing to take harsher measures. Maryland's election of Unionist Governor Augustus Bradford in November 1861 ensured that Maryland would remain part of the Union. Perhaps even more critical than Maryland was Kentucky, which provided access to key rivers and served as a gateway to Tennessee and the Midwest. Hoping to avoid upsetting the delicate balance in the state, Lincoln publicly ordered military leaders to respect Kentucky's declared neutrality, but quietly provided support to Kentucky Unionists. The Confederates were the first to violate this neutrality, seizing control of the town of Columbus, while the Union would capture the important town of Paducah. Like Kentucky, Missouri controlled access to key rivers and had a large pro-Confederate population. Lincoln appointed General John C. Frémont to ensure Union control of the area, but Frémont alienated many in the state by declaring martial law and issuing a proclamation freeing slaves that belonged to rebels. Lincoln removed Frémont and reversed the order, but Missouri emerged as the most problematic of the border states for Lincoln.[86]

Eastern theater to 1864

[edit]1861 and the Peninsula campaign

[edit]After the defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, Lincoln summoned Major General George B. McClellan to replace McDowell. McClellan had won minor battles in the Western Virginia campaign, and those victories had allowed Unionist West Virginia to hold the Wheeling Convention and eventually secede from Virginia.[87] With Lincoln's support, McClellan rejected Scott's Anaconda Plan, instead proposing a strike against Virginia which would end the war with one climactic battle.[88] After Scott retired in late 1861, Lincoln appointed McClellan general-in-chief of all the Union armies.[89] McClellan, a young West Point graduate, railroad executive, and Pennsylvania Democrat, took several months to plan and attempt his Peninsula campaign. The campaign's objective was to capture Richmond by moving the Army of the Potomac by boat to the Virginia Peninsula and then overland to the Confederate capital. McClellan's repeated delays frustrated Lincoln and Congress, as did his position that no troops were needed to defend Washington.[90]

In response to Bull Run, Congress established the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to provide oversight of military operations.[91] Throughout the war, the committee would investigate generals deemed incompetent or insufficiently aggressive. Aside from the committee's activities, Congress would generally defer to Lincoln's leadership throughout the war.[92] A group of congressmen known as the Radical Republicans often became frustrated with Lincoln's conduct of the war and reluctance to immediately push abolition, but Lincoln was able to maintain good relations with many of the Radical Republican leaders, including Senator Charles Sumner. Congressional Democrats, on the other hand, tended to oppose Lincoln's policies regarding both the war and slavery.[93]

In January 1862, Lincoln, frustrated by months of inaction, ordered McClellan to begin the offensive by the end of February.[94] When McClellan still failed to launch his attack, members of Congress urged Lincoln to replace McClellan with McDowell or Frémont, but Lincoln decided to retain McClellan as commander of Army of the Potomac over either potential replacement. He did, however, remove McClellan as general-in-chief of the army in May, leaving the office vacant. McClellan moved against Confederate forces in March, and the Army of Potomac fought the bloody-but-inconclusive Battle of Seven Pines at the end of May. Following the battle, Robert E. Lee took command of Confederate forces in Virginia, and he led his forces to victory in the Seven Days Battles, which effectively brought the Peninsula Campaign to a close.[95]

Second Bull Run, Antietam, and Fredericksburg

[edit]

In late June 1862, while the Army of the Potomac was fighting the Seven Days Battles, Lincoln appointed John Pope to command the newly-formed Army of Virginia. On July 11, Lincoln summoned Henry Halleck from the Western Theater of the war to take command as general-in-chief of the army. Shortly thereafter, Lincoln asked Ambrose Burnside to replace McClellan as commander of the Army of the Potomac, but Burnside, who was close friends with McClellan, declined the post.[96] Pope's forces moved South towards Richmond, and in late August, the Army of Virginia met the Confederate army in the Second Battle of Bull Run, which was another major Union defeat. Following the battle, Lincoln turned to McClellan again, placing him in command of the Army of Virginia as well as the Army of Potomac.[97]

Shortly after McClellan's return to command, General Lee's forces crossed the Potomac River into Maryland, leading to the Battle of Antietam in September 1862.[98] The ensuing Union victory was among the bloodiest in American history, but it enabled Lincoln to announce that he would issue an Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, which he did.[99] Following the battle, McClellan resisted the president's demand that he pursue Lee's retreating and exposed army.[100] The mid-term elections in 1862 brought the Republicans severe losses due to sharp disfavor with the administration over its failure to deliver a speedy end to the war, as well as rising inflation, new taxes, rumors of corruption, the suspension of habeas corpus, the military draft law, and fears that freed slaves would undermine the labor market. The Emancipation Proclamation gained votes for the Republicans in the rural areas of New England and the upper Midwest, but it lost votes in the cities and the lower Midwest.[101] After the 1862 mid-term elections, Lincoln, frustrated with McClellan's continued inactivity, replaced McClellan with Burnside.[102]

Against the advice of the president, Burnside prematurely launched an offensive across the Rappahannock River and was stunningly defeated by Lee at the Battle of Fredericksburg in December. Not only had Burnside been defeated on the battlefield, but his soldiers were disgruntled and undisciplined. Desertions during 1863 were in the thousands and they increased after Fredericksburg.[103] The defeat also amplified the criticisms of Radical Republicans such as Lyman Trumbull and Benjamin Wade, who believed that Lincoln had mishandled the war, particularly with regards to his selection of generals.[104]

Gettysburg campaign

[edit]"Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate, we can not consecrate, we can not hallow, this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

Following the Battle of Fredericksburg, Lincoln reassigned Burnside to the western theater and replaced Burnside with General Joseph Hooker, who had served in several battles of the eastern theater.[105] With the war dragging on, Lincoln signed the Enrollment Act, which provided for the first military draft in U.S. history.[106] The draft law sparked harsh reactions, including draft riots in New York City and other locations. In April 1863, Hooker began his offensive towards Richmond, and his army encountered Lee's at the Battle of Chancellorsville. Despite possessing a larger army, the Union suffered another major loss at Chancellorsville, though the Confederates also suffered a high number of casualties, including the death of General Stonewall Jackson.[107] Following the Confederate victory, Lee decided to take the offensive, launching the Gettysburg campaign in June 1863. Lee hoped that Confederate victories in the offensive would empower Lincoln's political opponents and convince the North that the Union could not win the war. After Hooker failed to stop Lee in the early stages of his advance, Lincoln replaced Hooker with General George Meade. Lee led his army into Pennsylvania, and was followed by Meade's Army of the Potomac. While many in the North fretted over Lee's advance, Lincoln saw the offensive as an opportunity to destroy a Confederate army.[108]

The Confederate and Union armies met at the Battle of Gettysburg on July 1. The battle, fought over three days, resulted in the highest number of casualties in the war. Along with the Union victory in the Siege of Vicksburg, the Battle of Gettysburg is often referred to as a turning point in the war. Though the battle ended with a Confederate retreat, Lincoln was dismayed that Meade had failed to destroy Lee's army. Feeling that Meade was a competent commander despite his failure to pursue Lee, Lincoln allowed Meade to remain in command of the Army of the Potomac. The Eastern Theater would be locked in a stalemate for the remainder of 1863.[109]

In November 1863, Lincoln was invited to Gettysburg to dedicate the first national cemetery and honor the soldiers who had fallen. His Gettysburg Address became a core statement of American political values. Defying Lincoln's prediction that "the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here", the Address became the most quoted speech in American history.[110] In 272 words, and three minutes, Lincoln asserted the nation was born not in 1789, following ratification of the United States Constitution, but with the 1776 Declaration of Independence. He defined the war as an effort dedicated to the principles of liberty and equality for all. The emancipation of slaves was now part of the national war effort. He declared that the deaths of so many brave soldiers would not be in vain, that slavery would end as a result of the losses, and the future of democracy in the world would be assured, that "government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth". Lincoln concluded that the Civil War had a profound objective: a new birth of freedom in the nation.[111][112]

Western theater and naval blockade

[edit]

Compared to the eastern theater of the war, Lincoln exercised less direct control over operations that took place west of the Appalachian Mountains. At the end of 1861, Lincoln ordered Don Carlos Buell, commander of the Department of the Ohio, and Henry Halleck, Frémont's replacement as commander of the Department of the Missouri, to coordinate support with Unionists in Kentucky and Eastern Tennessee.[113] General Ulysses S. Grant quickly earned Lincoln's attention, winning the first significant Union victory at the Battle of Fort Henry and earning a national reputation with his victory at the Battle of Fort Donelson.[114] The Confederates were driven from Missouri early in the war as a result of the March 1862 Battle of Pea Ridge.[115] In April 1862, U.S. Naval forces under the command of David Farragut captured the important port city of New Orleans.[116] Grant won further victories at the Battle of Shiloh[117] and the Siege of Vicksburg, which cemented Union control of the Mississippi River and is considered one of the turning points of the war.[118] In October 1863, Lincoln appointed Grant as the commander of the newly created Division of the Mississippi, giving him command of the Western Theater.[119] Grant and Generals Hooker, George H. Thomas, and William Tecumseh Sherman led the Union to another major victory at the Third Battle of Chattanooga in November, driving Confederate forces out of Tennessee.[120] The capture of Chattanooga left Georgia vulnerable to attack, raising the possibility of a Union march to the Atlantic Ocean, which would divide the Confederacy.[121]

In April 1861, Lincoln announced the Union blockade of all Southern ports; commercial ships could not get insurance and regular traffic ended. The South blundered in embargoing cotton exports in 1861 before the blockade was effective; by the time they realized the mistake, it was too late. "King Cotton" was dead, as the South could export less than 10 percent of its cotton.[122] The Confederate Navy briefly challenged Union naval supremacy by building an ironclad warship known as the CSS Virginia, but the Union responded by building its own ship, the USS Monitor, which effectively neutralized the Confederate naval threat.[123] The blockade shut down the ten Confederate seaports with railheads that moved almost all the cotton, especially New Orleans, Mobile, and Charleston. By June 1861, warships were stationed off the principal Southern ports, and a year later nearly 300 ships were in service.[122] Surdam argues that the blockade was a powerful weapon that eventually ruined the Southern economy, at the cost of few lives in combat. Practically, the entire Confederate cotton crop was useless (although it was sold to Union traders), costing the Confederacy its main source of income. Critical imports were scarce and the coastal trade was largely ended as well.[124] The measure of the blockade's success was not the few ships that slipped through, but the thousands that never tried it. Merchant ships owned in Europe could not get insurance and were too slow to evade the blockade; they simply stopped calling at Confederate ports.[125]

Grant takes command

[edit]

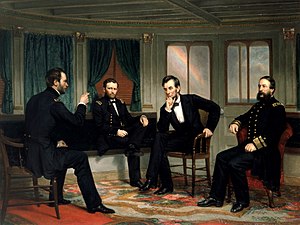

Grant was one of the few senior generals that Lincoln did not know personally, and the president was not able to visit the Western Theater of the war. Nonetheless, Lincoln came to appreciate the battlefield exploits of Grant.[126] Responding to criticism of Grant after Shiloh, Lincoln had said, "I can't spare this man. He fights."[127] In March 1864, Grant was summoned to Washington to succeed Halleck as general-in-chief, while Halleck took on the role of chief-of-staff.[128] Meade remained in formal command of the Army of the Potomac, but Grant would travel with the Army of the Potomac and direct its actions. Lincoln also obtained Congress's consent to reinstate for Grant the rank of Lieutenant General, which no U.S. officer had held since George Washington.[129] Grant ordered Meade to destroy Lee's army, while he ordered General Sherman, now in command of Union forces in the Western Theater, to capture Atlanta. Lincoln strongly approved of Grant's new strategy, which focused on the destruction of Confederate armies rather than the capture of Confederate cities.[130]

Two months after being promoted to general-in-chief, Grant embarked upon his bloody Overland Campaign. This campaign is often characterized as a war of attrition, given high Union losses at battles such as the Battle of the Wilderness and Cold Harbor. Even though they had the advantage of fighting on the defensive, the Confederate forces had a similarly high level of casualties.[131] The high casualty figures alarmed many in the North,[132] but, despite the heavy losses, Lincoln continued to support Grant.[133]

While Grant's campaign continued, General Sherman led Union forces from Chattanooga to Atlanta, defeating Confederate Generals Joseph E. Johnston and John Bell Hood along the way. Sherman's victory in the September 2 Battle of Atlanta boosted Union morale, breaking the pessimism that had set in throughout 1864.[134] Hood's forces left the Atlanta area to menace Sherman's supply lines and invade Tennessee in the Franklin-Nashville Campaign. General John Schofield defeated Hood at the Battle of Franklin, and General Thomas dealt Hood a massive defeat at the Battle of Nashville, effectively destroying Hood's army.[135] Lincoln authorized the Union army to target the Confederate infrastructure—such as plantations, railroads, and bridges—hoping to shatter the South's morale and weaken its economic ability to continue fighting. Leaving Atlanta, and his base of supplies, Sherman's army marched east with an unknown destination, laying waste to about 20 percent of the farms in Georgia in his "March to the Sea". He reached the Atlantic Ocean at Savannah, Georgia in December 1864. Following the March to the Sea, Sherman turned North through South Carolina and North Carolina to approach the Lee's army from the south.[136]

During the Valley Campaigns of 1864, Confederate general Jubal Early crossed the Potomac River, and advanced into Maryland. On July 11, two days after defeating Union forces under General Lew Wallace in the Battle of Monocacy, Early attacked Fort Stevens, an outpost on the defensive perimeter of Washington. Lincoln watched the combat from an exposed position; at one point during the skirmish Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. is said to have shouted at him, "Get down, you damn fool, before you get shot!", but this is commonly regarded as apocryphal.[137][138] Afterward, Grant created the Army of the Shenandoah and put Sheridan in command. Sheridan quickly repelled Early and suppressed the Confederate guerrillas in the Shenandoah Valley.[139]

Election of 1864

[edit]

With Democratic gains in the 1862 and 1863 midterm elections, Lincoln felt increasing pressure to finish the war before the end of his term in early 1865.[140] Hoping to rally unionists of both parties, Lincoln urged Republican leaders to adopt a new label for the 1864 election: the National Union Party.[141] By the end of 1863, Lincoln had won the respect of many, but his re-nomination was not assured, as no president had won a second term since Andrew Jackson in 1832. Chase emerged as the most prominent potential intra-party challenger, and Senator Samuel C. Pomeroy led a covert campaign for Chase's nomination.[142] Much of the support for Chase came from abolitionists who were frustrated by Lincoln's unwillingness to push for the immediate end of slavery and his willingness to work with conservative Unionist leaders in the South.[143] Pomeroy's attempts to galvanize support for Chase backfired as they generated a groundswell of support for Lincoln's re-nomination, and Chase announced in early 1864 that he was not a candidate for the presidential nomination.[144] After Chase decided not to run, anti-slavery activists cast about for a new candidate. In May 1864, a group led by Wendell Phillips nominated John C. Frémont for president. Most abolitionist leaders and Radical Republicans, including William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, and Charles Sumner, decided to support Lincoln over Frémont, as they believed that Frémont's candidacy would ultimately help Democrats more than the abolitionist cause.[145] Frémont himself eventually endorsed this view, and he withdrew from the race in favor of Lincoln in September 1864.[145]

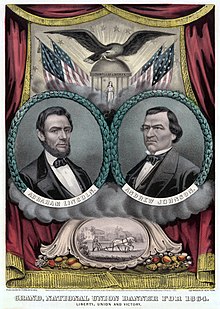

Despite recent setbacks in the Western Theater of the war, the June 1864 National Union National Convention nominated Lincoln for president. Though Hamlin hoped to be re-nominated as vice president, the convention instead nominated Andrew Johnson, the military governor of Tennessee. Lincoln had refused to weigh in on his preferred running mate, and the convention chose to nominate Johnson, a Southern War Democrat, in order to boost the party's appeal to Unionists of both parties.[146] The party platform called for the unconditional surrender of the Confederacy, and also endorsed open immigration policies, the construction of a transcontinental railroad, and the establishment of a national currency.[147]

By August, Republicans across the country were experiencing feelings of extreme anxiety, fearing that Lincoln would be defeated. The outlook was so grim that Thurlow Weed told the president directly that his "re-election was an impossibility." Acknowledging this, Lincoln wrote and signed a pledge that, if he should lose the election, he would nonetheless defeat the Confederacy by an all-out military effort before turning over the White House:[148]

This morning, as for some days past, it seems exceedingly probable that this Administration will not be re-elected. Then it will be my duty to so co-operate with the President elect, as to save the Union between the election and the inauguration; as he will have secured his election on such ground that he cannot possibly save it afterwards.[149]

Lincoln's re-election prospects grew brighter after the Union Navy seized Mobile Bay in late August and General Sherman captured Atlanta a few weeks later.[150] These victories relieved Republicans' defeatist anxieties, energized the Union-Republican alliance, and helped to restore popular support for the administration's war strategy.[151] The 1864 Democratic National Convention met at the end of August, nominating General George McClellan as its presidential candidate. The divided Democrats adopted a platform calling for peace with the Confederacy, but McClellan himself favored continuing the war. McClellan agonized over accepting the nomination, but after the Union victory in Atlanta, he accepted the nomination with a public letter.[146]

Confederate leaders hoped that a McClellan victory would lead to the beginning of peace negotiations, potentially leaving an independent Confederacy in place.[152] The Republicans mobilized support against the Democratic platform, calling it "The Great Surrender to the Rebels in Arms."[153] Lincoln won a major victory, taking 55% of the popular vote and 212 of the 233 electoral votes.[154] Lincoln's proportion of the popular was the largest that any presidential candidate had won since Andrew Jackson's 1832 re-election. Republican victories extended to other races, as the party gained dominant majorities in both houses of Congress and Republicans won nearly all of the gubernatorial races.[155]

Confederate surrender

[edit]Following the Overland Campaign, Grant's army reached the town of Petersburg, beginning the Siege of Petersburg in June 1864.[156] The Confederacy lacked reinforcements, so Lee's army shrank with every costly battle. Lincoln and the Republican Party mobilized support for the draft throughout the North and replaced the Union losses.[157] As Grant continued to wear down Lee's forces, efforts to discuss peace began. After Lincoln won reelection in November 1864, Francis Preston Blair, a personal friend of both Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, unsuccessfully encouraged Lincoln to make a diplomatic visit to Richmond.[158] Blair had advocated to Lincoln that the war could be brought to a close by having the two opposing sections of the nation stand down in their conflict, and reunite on grounds of the Monroe Doctrine in attacking the French-installed Emperor Maximilian in Mexico.[159] Though wary of peace efforts which could threaten his goal of emancipation, Lincoln did eventually agree to meet with the Confederates.[160] On February 3, 1865, Lincoln and Seward held a conference at Hampton Roads with three representatives of the Confederate government—Vice President Alexander H. Stephens, Senator Robert M. T. Hunter, and Assistant Secretary of War John A. Campbell—to discuss terms to end the war. Lincoln refused to allow any negotiation with the Confederacy as a coequal; his sole objective was an agreement to end the fighting and the meetings produced no results.[161]

Grant ground down the Confederate army across several months of trench warfare. Due to the city's important location, the fall of Petersburg would likely lead to the fall of Richmond, but Grant feared that Lee would decide to move South and link up with other Confederate armies. In March 1865, with the fall of Petersburg appearing imminent, Lee sought to break through the Union lines at the Battle of Fort Stedman, but the Confederate assault was repulsed. On April 2, Grant launched an attack that became known as the Third Battle of Petersburg, which ended with Lee's retreat from Petersburg and Richmond. In the subsequent Appomattox Campaign, Lee sought to link up with General Joseph E. Johnston, who was positioned in North Carolina, while Grant sought to force the surrender of Lee's army.[162] On April 5, Lincoln visited the vanquished Confederate capital. As he walked through the city, white Southerners were stone-faced, but freedmen greeted him as a hero, with one admirer remarking, "I know I am free for I have seen the face of Father Abraham and have felt him".[163] On April 9, Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox and the war was effectively over.[164] Following Lee's surrender, other rebel armies soon did as well, and there was no subsequent guerrilla warfare as had been feared.[citation needed]

Slavery and Reconstruction

[edit]

Early actions on slavery

[edit]Throughout the first year and a half of his presidency, Lincoln made it clear that the North was fighting the war to preserve the Union and not to end slavery. Though unwilling to publicly declare the abolition of slavery as a war goal, Lincoln considered various plans that would provide for the eventual abolition of slavery and explored the idea of compensated emancipation, including one proposal that would have seen all Delaware slaves freed by 1872.[165] He also met with Frederick Douglass and other black leaders, discussing the possibility of a colonization project in Central America.[166] Abolitionists criticized Lincoln for his slowness in moving from his initial position of non-interference with slavery to one of emancipation. In an August 1862 letter to anti-slavery journalist Horace Greeley, Lincoln explained:

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was".... My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.[167]

As the Civil War continued, freeing the slaves became an important wartime measure for weakening the rebellion by destroying the economic base of its leadership class. In August 1861, Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act of 1861, which authorized court proceedings to confiscate the slaves of anyone who participated in or aided the Confederate war effort. The act however, did not specify whether the slaves were free.[168] In April 1862, Lincoln signed a law abolishing slavery in Washington, D.C., and, in June, he signed a law abolishing slavery in all federal territories. The following month, Lincoln signed the Confiscation Act of 1862, which declared that all Confederate slaves taking refuge behind Union lines were to be set free.[169]

Emancipation Proclamation

[edit]Union victories in 1861 and 1862 secured the border states, which in turn freed Lincoln's hand to pursue more aggressive anti-slavery policies.[170] Additionally, many Northerners came to support abolition during the war due to the influence of religious leaders like Henry Ward Beecher and journalists like Horace Greeley.[171] The same month that Lincoln signed the Second Confiscation Act, he also privately decided that he would pursue emancipation as a war goal. Although, before the war, Lincoln accepted the consensus that the federal government did not have the power to interfere with slavery in the states where it existed, he now believed that, under his power as "Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy" under Article II, section 2 of the United States Constitution, he could, "as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion", emancipate the slaves in the states in rebellion. On July 22, 1862, Lincoln read to his cabinet a preliminary draft of a proclamation calling for emancipation of all slaves in the Confederacy. As the Union had suffered several defeats in the early part of the war, Seward convinced Lincoln to announce this emancipation plan after a significant Union victory so that it would not seem like a move of desperation.[172] Lincoln waited two months until after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam.[173]

Lincoln issued the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation on September 22, 1862, five days after the Battle of Antietam. It provided that, in any states in rebellion on January 1, 1863, the slaves would be free. Lincoln kept his promise, and, on January 1, 1863, he issued the Final Emancipation Proclamation, declaring free the slaves in the ten states that were still in rebellion. The proclamation did not cover the nearly 500,000 slaves in the slaveholding border states that had remained in the Union; nor did it apply to Tennessee or West Virginia, both of which were largely under the control of Union forces.[174] Also specifically exempted were New Orleans and 13 named parishes of Louisiana, which were mostly under federal control at the time of the Proclamation.[175] Despite these exemptions and the delayed effect of the proclamation, the Emancipation Proclamation added a second purpose of the war, making its goal ending slavery as well as restoring the Union.[176] The Proclamation was well received by most Republicans, but many Democrats strongly disapproved, and the latter party won several victories in the 1862 midterm elections.[177]

Reconstruction

[edit]As Southern states were subdued, critical decisions had to be made as to the leadership and policies of these states. Louisiana, which had a larger slave population than other Confederate states occupied early in the war, became the center of discussion regarding Reconstruction under Lincoln and military governor Benjamin Butler.[178] Butler and his successor, Nathaniel P. Banks, implemented a labor system in which free blacks worked as laborers on white-owned plantations. This model, which paid blacks wages but also represented a continuation of plantation agriculture, was adopted throughout much of the occupied South.[179] Banks also presided over the ratification of a new state constitution that banned slavery, but did not guarantee free blacks the right to vote.[180]

After 1862, Democrats like Reverdy Johnson sought the withdrawal of the Emancipation Proclamation and amnesty for the Confederates. By contrast, Radical Republicans like Sumner argued that rebel Southerners had lost all rights by attempting to secede from the Union. In his ten percent plan, Lincoln sought to find a middle ground, calling for the emancipation of Confederate slaves and the re-integration of Southern states once ten percent of voters in a state took an oath of allegiance to the U.S. and pledged to respect emancipation.[181] Radical Republicans countered with the Wade–Davis Bill, a Reconstruction plan that included protections for the rights of freed African Americans and required fifty percent of voters to swear the "Ironclad Oath" indicating that they had never and never would support a rebellion against the United States. As the Wade–Davis Bill interfered with Lincoln's plans for the readmission of Louisiana and Arkansas, Lincoln pocket vetoed the bill in late 1864.[182]

Even as they cooperated on most other issues, Lincoln and congressional Republicans continued to clash over Reconstruction policies after the 1864 election. Many in Congress sought far-reaching reforms to Southern society that went beyond the abolition of slavery, and they refused to recognize Lincoln's reconstituted Southern governments. Disagreements within Congress prevented the passage of any Reconstruction bill or the recognition of governments in Arkansas and Louisiana.[183] As the war came to a close, Lincoln indicated an openness to some of the proposals of the Radical Republicans, and he signed a bill creating the Freedmen's Bureau.[184] Established as a temporary institution, the Freedmen's Bureau was designed to provide food and other supplies to free blacks in the South, and was also authorized to grant confiscated land to former slaves.[185] Lincoln did not take a definitive stand on black suffrage, stating only that "very intelligent blacks" and those that had served in the military should be granted the right to vote.[186]

Historian Eric Foner notes that no one knows what Lincoln would have done about Reconstruction had he served out his second term, but he adds,

Unlike Sumner and other Radicals, Lincoln did not see Reconstruction as an opportunity for a sweeping political and social revolution beyond emancipation. He had long made clear his opposition to the confiscation and redistribution of land. He believed, as most Republicans did in April 1865, that the voting requirements should be determined by the states. He assumed that political control in the South would pass to white Unionists, reluctant secessionists, and forward-looking former Confederates. But time and again during the war, Lincoln, after initial opposition, had come to embrace positions first advanced by abolitionists and Radical Republicans.... Lincoln undoubtedly would have listened carefully to the outcry for further protection for the former slaves.... It is entirely plausible to imagine Lincoln and Congress agreeing on a Reconstruction policy that encompassed federal protection for basic civil rights plus limited black suffrage, along the lines Lincoln proposed just before his death."[187]

Thirteenth Amendment

[edit]In December 1863, a proposed constitutional amendment that would outlaw slavery was introduced in Congress; though the Senate voted for the amendment with the necessary two-thirds majority, the amendment did not receive sufficient support in the House.[188] On accepting the National Union Party nomination in 1864, Lincoln told the party that he would seek to ratify a constitutional amendment that would abolish slavery in the United States.[146] After winning re-election, Lincoln made ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment (as it would become known) a top priority. With the aid of large Republican majorities in both houses of Congress, Lincoln believed that he could permanently end the institution of slavery in the United States.[189] Though he had largely avoided becoming involved in congressional legislative processes, Lincoln gave the ratification struggle his full attention. Rather than waiting for the 39th Congress to convene in March, Lincoln pressed the lame duck session of the 38th Congress to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment as soon as possible. After an extensive lobbying campaign by Lincoln and Seward, the House narrowly cleared the two-thirds threshold in a 119–56 vote.[189] The Thirteenth Amendment was sent to the states for ratification, and Secretary of State Seward proclaimed its adoption on December 18, 1865. With the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment, some abolitionist leaders viewed their work as complete, though Frederick Douglass believed that "slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot."[190]

Other domestic issues

[edit]

In the decades prior to the Civil War, Southern congressmen had blocked the passage of various economic proposals, including federal funding for internal improvements, support for higher education, and increased tariff rates designed to protect domestic manufacturing against foreign competition.[191] With the secession of several Southern states, the Republicans dominated both houses of Congress and were free to implement the party's economic agenda.[192] Lincoln adhered to the Whig understanding of separation of powers under the Constitution, which gave Congress primary responsibility for writing the laws while the executive enforced them.[193] Lincoln and Secretary of the Treasury Chase contributed to the drafting and passage of some legislation, but congressional leaders played the dominant role in formulating domestic policy outside of military affairs.[194] Throughout his presidency, Lincoln vetoed only four bills passed by Congress; the only important one was the Wade-Davis Bill.[193]

The 37th Congress, which met from 1861 to 1863, passed 428 public acts, more than double the number of the 27th Congress, which had previously held the record for most public acts passed. The 38th Congress, meeting from 1863 to 1865, passed 411 public acts. Many of these bills were designed to raise revenue for funding the war, as federal expenses increased seven-fold in the first year of the Civil War.[194]

Fiscal and monetary policy

[edit]After the Battle of Fort Sumter, Lincoln and Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase faced the challenge of funding the war. Congress quickly approved Lincoln's request to assemble a 500,000-man army, but initially resisted raising taxes to pay for the war.[195] After the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run, Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1861, which imposed the first federal income tax in U.S. history. The act created a flat tax of three percent on incomes above $800 ($27,100 in current dollar terms). This taxation of income reflected the increasing amount of wealth held in stocks and bonds rather than property, which the federal government had taxed in the past.[196] As the average urban worker made approximately $600 per year, the income tax burden fell primarily on the rich.[197]

Lincoln also signed the second and third Morrill Tariffs, the first having become law in the final months of Buchanan's tenure. These tariff acts raised import duties considerably compared to previous tariff rates, and they were designed to both raise revenue and protect domestic manufacturing against foreign competition. During the war, the tariff also helped manufacturers off-set the burden of new taxes. Compared to pre-war levels, the tariff would remain relatively high for the remainder of the 19th century.[198] Throughout the war, members of Congress would debate whether to raise further revenue primarily through increased tariff rates, which most strongly affected rural areas in the West, or increased income taxes, which most strongly affected wealthier individuals in the Northeast.[199]

The revenue measures of 1861 proved inadequate for the funding of the war, forcing Congress to pass further bills designed to generate revenue.[200] In February 1862, Congress passed the Legal Tender Act, which authorized the minting of $150 million of "greenbacks." Greenbacks were the first banknotes issued by the federal government of the United States since the end of the American Revolution. Greenbacks were not backed by gold or silver, but rather by the promise of the United States government to honor their value. By the end of the war, $450 million worth of greenbacks were in circulation.[201] Congress also passed the Revenue Act of 1862, which established an excise tax that affected nearly every commodity,[202] as well as the first national inheritance tax.[203] The Revenue Act of 1862 also added a progressive taxation structure to the federal income tax, implementing a tax of five percent on incomes above $10,000.[204] To collect these taxes, Congress created the Office of the Commissioner of Internal Revenue within the Treasury Department.[203]

Despite these new measures, funding the war continued to be a difficult struggle for Chase and the Lincoln administration.[205] The government continued to issue greenbacks and borrow large amounts of money, and the United States national debt grew from $65 million in 1860 to $2 billion in 1866.[201] Congress passed the Revenue Act of 1864, which represented a compromise between those who favored a more progressive tax structure and those who favored a flat tax.[206] The act established a five percent tax on incomes greater than $600, a ten percent tax on incomes above $10,000, and raised taxes on businesses.[203] In early 1865, Congress passed another tax increase, levying a tax of ten percent on incomes above $5000.[207] By the end of the war, the income tax constituted about one-fifth of the revenue of the federal government.[203] The federal inheritance tax would remain in effect until its repeal in 1870, while the federal income tax would be repealed in 1872.[208]

Lincoln also took action against rampant fraud during the civil war, by enacting the False Claims Act in 1863. This law, also known as the "Lincoln Law," made it possible for private citizens to file false claims qui tam lawsuits on behalf of the U.S. government and also protect the US government from contractors providing faulty goods to the Union army.[209][210] During this time, any person who submitted a false claim would have to pay double the amount of the government's damages plus $2,000 per false claim.[211] The False Claims Act has been amended several times with a notable amendment being made in 1986 when Congress strengthened the law, and it still remains a model of a successful whistleblower law that works to deter contractors from defrauding the government.[212]

Hoping to stabilize the currency, Chase convinced Congress to pass the National Banking Act in February 1863, as well as a second banking act in 1864. Those acts established the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency to oversee "national banks," which would be subject to federal, rather than state, regulation. In return for investing a third of their capital in federal bonds, these national banks were authorized to issue federal banknotes.[205] After Congress imposed a tax on private banknotes in March 1865, federal banknotes would become the dominant form of paper currency in the United States.[197]

Reforms

[edit]Many of the bills passed by the 37th and 38th Congress were designed at least in part to pay for the war, but other bills instituted long-term reforms in areas unrelated to revenue.[213] Congress passed the Homestead Act in May 1862, making millions of acres of government-held land in the West available for purchase at very low cost. Under the act, settlers would be granted 160 acres of public land if they invested five years into developing the land.[214] The Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act, also enacted in 1862, provided government grants for agricultural colleges in each state. The law gave each member of Congress 30,000 acres of public land to sell, with proceeds funding the establishment of land-grant colleges.[215] Another 1862 law created the Department of Agriculture to aid farming in the United States. The Pacific Railway Acts of 1862 and 1864 granted federal support for the construction of the United States' First transcontinental railroad, which was completed in 1869.[216]

In June 1864, Lincoln approved the Yosemite Grant enacted by Congress, which provided unprecedented federal protection for the area now known as Yosemite National Park.[217] Lincoln is also largely responsible for the institution of the Thanksgiving holiday in the United States.[218] In 1863, Lincoln declared the final Thursday in November of that year to be a day of Thanksgiving. Before Lincoln's presidency, Thanksgiving, while a regional holiday in New England since the 17th century, had been proclaimed by the federal government only sporadically and on irregular dates.[218]

Domestic dissent and Confederate sympathizers

[edit]In the aftermath of the attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus and began to imprison suspected Confederate sympathizers. In 1861, Seward set up a special office in the State Department designed to monitor internal security, and the federal government and local police officers worked together to suppress those suspected of actively supporting the Confederacy.[219] Among those imprisoned was John Merryman, an officer of the Maryland militia who had cut telegraph lines leading to Washington. In the subsequent case of Ex parte Merryman, Chief Justice Taney asserted that only Congress had the right to suspend habeas corpus. In a message to Congress delivered in July 1861, Lincoln responded by arguing that his actions had been constitutional and necessary given the threat posed by the Confederacy.[220] Congress later passed the Habeas Corpus Suspension Act 1863, which provided congressional authorization to the president to suspend habeas corpus and placed limits on the administration's ability to indefinitely hold prisoners.[221]

As the war continued, many in the North came to resist the sacrifices required by the war, and recruiting declined.[222] After state and local efforts failed to furnish the troops necessary for the war, Congress instituted a draft through passage of the March 1863 Enrollment Act. The conscription act included various exemptions and allowed potential draftees to pay for substitutes, but it nonetheless proved unpopular in many communities and among many state and local leaders.[223] Opposition to the draft was especially strong among Irish Americans, urban laborers, and others who could not afford to pay for substitutes. The New York City draft riots of July 1863 saw mobs attack soldiers, policemen, and African Americans, and was only subdued after Lincoln diverted soldiers from the Gettysburg Campaign. Rejecting calls to institute martial law in the city, Lincoln appointed John Adams Dix to oversee New York City, and Dix allowed the city to hold civilian trials on those who had participated in the riots.[224]

Clement Vallandigham, a Copperhead Democrat from Ohio, emerged as one of the most prominent critics of the war. General Ambrose Burnside arrested Vallandigham in May 1863 after the latter strongly criticized the draft and other wartime policies. A military commission subsequently sentenced Vallandigham to imprisonment until the end of the war, but Lincoln intervened to have Vallandigham released into Confederate territory. Ohio Democrats nonetheless nominated Vallandigham for governor in June 1863.[225] Vallandigham's defeat in the 1863 election, along with Democratic electoral defeats elsewhere in 1863, represented a major victory for Lincoln and the Republicans as it signified public support for the war.[226]

Conflicts with Native Americans

[edit]Conflicts with Native Americans on the American frontier continued during the Civil War, as American settlers continued to push west.[227] In 1862, Lincoln sent General Pope to put down the "Sioux Uprising" in Minnesota. Presented with 303 execution warrants for convicted Santee Dakota who were accused of killing innocent farmers, Lincoln conducted his own personal review of each of these warrants, eventually approving 39 for execution (one was later reprieved).[228] In his final two annual messages to Congress Lincoln called for reform of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and federal Indian policy. However, as the war to preserve the Union was Lincoln's primary concern, he simply allowed the system to function unchanged for the balance of his presidency.[229]

States admitted to the Union