Spring and Autumn Annals

| Spring and Autumn Annals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

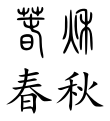

Chunqiu in seal script (top) and regular script (bottom) characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | springs and autumns | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Kinh Xuân Thu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 經春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 춘추 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 春秋 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | しゅんじゅう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Spring and Autumn Annals is an ancient Chinese chronicle that has been one of the core Chinese classics since ancient times. The Annals is the official chronicle of the State of Lu, and covers a 242-year period from 722 to 481 BCE. It is the earliest surviving Chinese historical text to be arranged in annals form.[1] Because it was traditionally regarded as having been compiled by Confucius—after a claim to this effect by Mencius—it was included as one of the Five Classics of Chinese literature.

The Annals records main events that occurred in Lu during each year, such as the accessions, marriages, deaths, and funerals of rulers, battles fought, sacrificial rituals observed, celestial phenomena considered ritually important, and natural disasters.[1] The entries are tersely written, averaging only 10 characters per entry, and contain no elaboration on events or recording of speeches.[1]

During the Warring States period (475–221 BCE), a number of commentaries to the Annals were created that attempted to elaborate on or find deeper meaning in the brief entries in the Annals. The Zuo Zhuan, the best known of these commentaries, became a classic in its own right, and is the source of more Chinese sayings and idioms than any other classical work.[1]

History and content

[edit]The Spring and Autumn Annals was likely composed in the 5th century BC.[1] By the time of Confucius, in the 6th century BC, the term 'springs and autumns' (chūnqiū 春秋, Old Chinese *tʰun tsʰiw) had come to mean 'year' and was probably becoming a generic term for 'annals' or 'scribal records'.[1] The Annals was not the only work of its kind, as many other Eastern Zhou states also kept annals in their archives.[2]

The Annals is a succinct scribal record that has around 18,000 total words, with terse entries that record events such as the accessions, marriages, deaths, and funerals of rulers, battles fought, sacrificial records observed, natural disasters, and celestial phenomena believed to be of ritual significance.[1] The entries/sentences average only 10 characters in length; the longest entry in the entire work is only 47 characters long, and a number of the entries are only a single character long.[1] There are 11 entries that read simply *tung 螽 (zhōng), meaning 'a plague of insects'—probably locusts.[a][1]

Some modern scholars have questioned whether the entries were ever originally intended as a chronicle for human readers, and have suggested that the Annals entries may have been intended as "ritual messages directed primarily to the ancestral spirits".[1]

Commentaries

[edit]

Since the text of this book is terse and its contents limited, a number of commentaries were composed to annotate the text, and explain and expand on its meanings. The Book of Han vol. 30 lists five commentaries:

- The Commentary of Zou (鄒氏傳)

- The Commentary of Jia (夾氏傳)

- The Gongyang Zhuan

- The Guliang Zhuan

- The Zuo Zhuan

No text of the Zou or Jia commentaries has survived. The surviving commentaries are known collectively as the Three Commentaries on the Spring and Autumn Annals (春秋三傳; Chūnqiū Sānzhuàn). Both the Book of Han and the Records of the Grand Historian provide detailed accounts of the origins of the three texts.

The Gongyang and Guliang commentaries were compiled during the 2nd-century BC, although modern scholars had suggested they probably incorporate earlier written and oral traditions of explanation from the period of Warring States. They are based upon different editions of the Spring and Autumn Annals, and are phrased as questions and answers.

The Zuo Zhuan, composed in the early 4th century BC, is a general history covering the period from 722 to 468 BC which follows the succession of the rulers of the state of Lu. In the 3rd-century AD, the Chinese scholar Du Yu interpolated the Zuo Zhuan with the Annals so that each entry of the Annals was followed by the corresponding passages of the Zuo Zhuan. Du Yu's version of the text was the basis for the "Right Meaning of the Annals" (春秋正義 Chūnqiū zhèngyì) which became the imperially authorised text and commentary on the Annals in 653 AD.[4]

During the late Han dynasty, there was a saying that the Guoyu was an "Outer Commentary" to the Spring and Autumn Annals.[5]

There is also the Chunqiu shiyu from the Mawangdui tombs detailing less information and some say shiyu was the teacher's name who wrote it.[6]

Influence

[edit]The Annals is one of the core Chinese classics and had an enormous influence on Chinese intellectual discourse for nearly 2,500 years.[1] This was due to Mencius' assertion in the 4th century BC that Confucius himself edited the Annals, an assertion which was accepted by the entire Chinese scholarly tradition and went almost entirely unchallenged until the early 20th century.[7] The Annals' terse style was interpreted as Confucius' deliberate attempt to convey "lofty principles in subtle words" (微言大義; wēiyán dàyì).[1] Not all scholars accepted this explanation: Tang dynasty historiographer Liu Zhiji believed the Commentary of Zuo was far superior to the Annals, and Song dynasty prime minister Wang Anshi famously dismissed the Annals as "a fragmentary court gazette" (斷爛朝報; duànlàn cháobào).[1] Some Western scholars have given similar evaluations: the French sinologist Édouard Chavannes referred to the Annals as "an arid and dead chronicle".[1]

The Annals have become so evocative of the era in which they were composed that it is now widely referred to as the Spring and Autumn period.[1]

Translations

[edit]

- Legge, James (1872), The Ch'un Ts'ëw with The Tso Chuen, The Chinese Classics, Vol. V, Hong Kong: Lane, Crawford, & Co. (part 1 and part 2 at the Internet Archive; also with Pinyin transliterations here).

- Couvreur, Séraphin (1914). Tch'ouen ts'ieou et Tso tschouan [Chunqiu and Zuozhuan] (in French). Ho Kien Fou: Mission Catholique. Reprinted (1951), Paris: Cathasia.

- Malmqvist, Göran (1971). "Studies on the Gongyang and Guliang Commentaries". Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities. 43: 67–222.

- Watson, Burton (1989). The Tso Chuan: Selections from China's Oldest Narrative History. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Miller, Harry (2015). The Gongyang Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals: A Full Translation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

See also

[edit]- Bamboo Annals

- Luxuriant Dew of the Spring and Autumn Annals

- Lüshi Chunqiu

- Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue

- Yanzi chunqiu

Note

[edit]- ^ Du Yu states that the disastrous 螽 are related to 蚣蝑 zhōngxū 'katydids'.[3] Schuessler (2007) reconstructs the Old Chinese pronunciation of 螽 as *C-juŋ, and compares it to Burmese ကျိုင် kyuing 'locust'.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Wilkinson (2012), p. 612.

- ^ Kern (2010), p. 46.

- ^ Du Yu, 《春秋經傳集解》 Chunqiu Zuozhuan - Collected Explanations. Sibu Congkan First Series version, "vol. 1" p. 69 of 189 quote: "螽……蚣蝑之屬為災"

- ^ Cheng (1993), p. 72.

- ^ Xu, Gan (1 January 2002). Balanced Discourses: A Bilingual Edition. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09201-1.

- ^ Shaughnessy, Edward (18 November 2019). Chinese Annals in the Western Observatory: An Outline of Western Studies of Chinese Unearthed Documents. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-1-5015-1710-5.

- ^ Cheng (1993), p. 67.

Works cited

[edit]- Cheng, Anne (1993). "Ch'un ch'iu 春秋, Kung yang 公羊, Ku liang 榖梁 and Tso chuan 左傳". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Early China Special Monograph Series. Vol. 2. Berkeley: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley. pp. 67–76. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Kern, Martin (2010). "Early Chinese literature, Beginnings through Western Han". In Owen, Stephen (ed.). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature, Volume 1: To 1375. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–115. ISBN 978-0-521-11677-0.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2012). Chinese History: A New Manual. Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series 84. Cambridge, MA: Harvard-Yenching Institute; Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-06715-8.

External links

[edit] Works related to 春秋左氏傳 (Spring and Autumn Annals – Commentary of Zuo) at Wikisource

Works related to 春秋左氏傳 (Spring and Autumn Annals – Commentary of Zuo) at Wikisource Works related to 春秋公羊傳 (Spring and Autumn Annals – Commentary of Gongyang) at Wikisource

Works related to 春秋公羊傳 (Spring and Autumn Annals – Commentary of Gongyang) at Wikisource Works related to 春秋穀梁傳 (Spring and Autumn Annals – Commentary of Guliang) at Wikisource

Works related to 春秋穀梁傳 (Spring and Autumn Annals – Commentary of Guliang) at Wikisource- Full text of Spring and Autumn Annals (Chinese)

- 1872 English translation by James Legge. Also at the Internet Archive: part 1 and part 2