Bucknell University

| |

Former name | University at Lewisburg (1846–1886)[1] |

|---|---|

| Type | Private liberal arts college |

| Established | 1846[1] |

| Endowment | $1.07 billion (2022)[2] |

| President | John C. Bravman[1] |

Academic staff | 423[3] |

| Undergraduates | 3,747[3] |

| Postgraduates | 40[3] |

| Location | , , U.S. 40°57′17″N 76°53′01″W / 40.95472°N 76.88361°W |

| Campus | 450 acres (1.8 km2)[3] |

| Colors | Blue and orange[4] |

| Nickname | Bison |

Sporting affiliations | NCAA Division I (FCS) Patriot League CWPA[3] |

| Mascot | Bucky the Bison[5] |

| Website | www |

| |

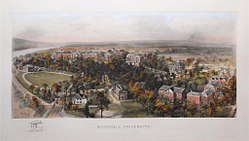

Bucknell University is a private liberal-arts college in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, United States. Founded in 1846 as the University at Lewisburg, it now consists of the College of Arts and Sciences, the Freeman College of Management, and the College of Engineering. It offers 65 majors and 70 minors in the sciences and humanities. Located just south of Lewisburg, the 445-acre (1.80 km2) campus rises above the West Branch of the Susquehanna River.

Approximately 3,700 undergraduate students and 50 graduate students attend the university. The school is a member of the Patriot League in NCAA Division I athletics. Its nickname is the Bucknell Bison, while its mascot is Bucky the Bison.

History

[edit]Founding and early years

[edit]Founded in 1846 as the University at Lewisburg, Bucknell traces its origin to a group of Baptists from White Deer Valley Baptist Church who deemed it "desirable that a Literary Institution should be established in Central Pennsylvania, embracing a High School for male pupils, another for females, a College and also a Theological Institution."[6]

The group's efforts for the institution began to crystallize in 1845, when Stephen William Taylor, a professor at Madison University (now Colgate University) in Hamilton, New York, was asked to prepare a charter and act as general agent for the development of the university. The charter for the University at Lewisburg, granted by the Pennsylvania General Assembly and approved by the governor on February 5, 1846, carried one stipulation–that $100,000 ($3,400,000 today) be raised before the new institution would be granted full corporate status.

In 1846, the "school preparatory to the University" opened in the basement of the First Baptist Church in Lewisburg. Known originally as the Lewisburg High School, it became in 1848 the Academic and Primary Department of the University at Lewisburg.[7]

The school's first commencement was held on August 20, 1851, for a graduation class of seven men. Among the board members attending was James Buchanan, who would become the 15th President of the United States. Stephen Taylor officiated as his last act before assuming office as president of Madison University. One day earlier, the trustees had elected Howard Malcom as the first president of the university, a post he held for six years.[8]

Female Institute

[edit]

Although the Female Institute began instruction in 1852, it wasn't until 1883 that college courses were opened to women. Bucknell, though, was committed to equal educational opportunities for women. This commitment was reflected in the words of David Jayne Hill of the Class of 1874, and president of the college from 1879 to 1888: "We need in Pennsylvania, in the geographical centre of the state, a University, not in the German but in the American sense, where every branch of non-professional knowledge can be pursued, regardless of distinction of sex. I have no well-matured plan to announce as to the sexes; but the Principal of the Female Seminary proposes to inaugurate a course for females equal to that pursued at Vassar; the two sexes having equal advantages, though not reciting together."[9] Within five years of opening, enrollment had grown so sharply that the college built a new hall–Larison Hall–to accommodate the Female Institute.

Benefactor William Bucknell

[edit]In 1881, facing dire financial circumstances, the college turned to William Bucknell, a charter member of the board of trustees, for help. His donation of $50,000 ($1,580,000 today) saved the college from ruin. In 1886, in recognition of Bucknell's support of the college, the trustees voted unanimously to change the name of the University at Lewisburg to Bucknell University.[10] Bucknell Hall, the first of several buildings given to the institution by Bucknell, was initially a chapel and for more than a half century the site of student theatrical and musical performances. Today, it houses the Stadler Center for Poetry.[11]

Continued expansion

[edit]

The 40 years from 1890 until 1930 saw a steady increase in the number of faculty members and students. When the Depression brought a drop in enrollment in 1933, several members of the faculty were "loaned" to found a new institution: Bucknell Junior College in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Today, that institution is a four-year university, Wilkes University, independent of Bucknell since 1947. The depression era also saw the commissioning by President Homer Rainey (1931–35) of architect Jens Larson to design Bucknell's master plan. Subsequent expansion of the university still largely adheres to this plan.[12]

The post-War period saw a dramatic increase in higher education enrollment across the United States, thanks first to the G.I. Bill and then to the baby boom. Like other institutions, Bucknell's campus grew to accommodate a growing student body, and the college broke ground on many of the academic buildings that comprise upper campus. Chief among these is the Ellen Clarke Bertrand Library, commissioned in 1946 under Bucknell President and former Governor of Maine Horace Hildreth and opened in 1951.[13] Other major additions from the building spree of the 1950s and 60s include the Olin Science Building and Coleman, Marts and Swartz Halls.

Building for the future

[edit]A growing reputation and changing expectations for undergraduate education in the United States called for improved facilities. The 1970s brought construction of the Elaine Langone Center, the Gerhard Fieldhouse and the Computer Center. In the 1980s, the capacity of Bertrand Library was doubled, facilities for engineering were substantially renovated, and the Weis Center for the Performing Arts was inaugurated.

Heading into the 21st century, new facilities for the sciences included the renovation of the Olin Science Building, the construction of the Rooke Chemistry Building in 1990 and a new Biology Building in 1991. The Weis Music Building was inaugurated in 2000, the O'Leary Building for Psychology and Geology opened in the fall of 2002, the new Kenneth Langone Recreational Athletic Center opened in 2003 and the Breakiron Engineering Building in 2004.[14]

Campus

[edit]Grounds

[edit]Bucknell's 450-acre (180 ha) campus comprises more than 100 buildings located over a gentle rise adjacent to the West Branch Susquehanna River. The campus is divided into Lower Campus and Upper Campus by Miller Run and the Grove, a stand of oak trees that ascends the slope. Lower Campus consists primarily of student housing and the institution's sports facilities. Upper Campus mainly contains academic buildings. It offers views northwest across the Buffalo Valley toward Mount Nittany and southeast across the Susquehanna River toward Montour Ridge. Bucknell's campus forms a cohesive architectural ensemble due to the sustained use of brick and the recurrent themes of Georgian style. The institution's first building, Taylor Hall, was constructed in 1848.[15] The oldest residential hall on the campus is Daniel C. Roberts Hall (originally known as Old Main in 1858). Its newest building, Holmes Hall, was inaugurated in 2021.

-

Vaughan Literature Building

-

Coleman Hall in winter

Non-academic facilities

[edit]

Rooke Chapel is the non-denominational setting for campus worship, weddings, and celebrations. The chapel was a gift of Robert Levi Rooke (class of 1913), a member of the board of trustees. The chapel is named in memory of Rooke's parents and was inaugurated on October 25, 1964.[16]

Christy Mathewson–Memorial Stadium is a 13,100-seat multi-purpose stadium built in 1924 and renovated in 1989, when it was also renamed in honor of Christy Mathewson (class of 1902), a New York Giants Hall of Fame pitcher.[17][18]

The Bucknell Farm was established in 2018, building on the success of the Lewisburg Community Garden, a partnership between Bucknell University and the Borough of Lewisburg.[19] The 5-acre (2.0 ha) organic farm overlooking Montour Ridge offers learning and service opportunities for students and provides fresh, local produce for the institution's dining system. Along with a 1.76-megawatt solar array installed in 2022,[20] the farm reflects Bucknell's commitment to achieving carbon neutrality by 2030 and long-term environmental sustainability.[21]

Bucknell Greenhouse is located on the fourth floor of the Biology Building. In 2023, the Century Plant (Agave americana) bloomed for the first time in thirty years.[22] The greenhouse contains three ecosystems: a desert, wetlands, and tropical and temperate forests.[23]

In 2023, the school began the first part of the Bucknell Greenway, what will be a 4-mile (6.4 km) educational recreation path around campus, while also connecting to the athletic fields across U.S. Route 15.[24]

Academics

[edit]Bucknell has a total enrollment of around 3,950 undergraduate and thirty graduate students. With around 400 faculty, the faculty to student ratio is 9:1, with the average class size of approximately twenty students. Bucknell has traditionally had strong engineering programs. With the addition for the Freeman College of Management in 2017, Bucknell offers a balance of foundational liberal-arts study and pre-professional training, a statistic reflected in the 25% of students who choose to double major.[25] In 2021, the largest majors were Accounting and Finance (79 graduates), Political Science and Government (76 graduates), and Economics (67 graduates).[26] For the years between 2015 and 2021, 18% of students reported pursuing post-graduate study within nine months of graduating.[27]

College of Arts and Sciences

[edit]

The College of Arts and Sciences anchors Bucknell University in the liberal-arts tradition. Its three divisions—arts and humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences and mathematics—host 275 faculty members in 34 departments and 66% percent of all students enrolled in fifty majors.[28] The college emphasizes intellectual community in diversity, transformative education for the common good, mentorship that encourages students to lead examined lives and leading-edge research and scholarship.[28]

College of Engineering

[edit]

Among American colleges that do not offer a PhD in engineering, Bucknell was ranked 7th, according to the 2024 edition of the U.S. News & World Report college ranking.[29] The same report ranked Computer Engineering 5th, Civil Engineering 3rd, Electrical Engineering 4th, and Mechanical Engineering 3rd.[29]

Freeman College of Management

[edit]Students can choose from five tracks leading to the Bachelor of Science in Business Administration degree: managing for sustainability, markets innovation and design, global management, accounting and financial management, or analytics and operations management. A five-year, dual degree in Engineering and Management is available for engineers with management career goals. In 2022, after four years as an independent college, The Freeman College of Management was ranked 17th among undergraduate business schools.[30]

Centers and institutes

[edit]

The Bucknell Humanities Center opened in 2017 with the inauguration of Hildreth-Mirza Hall. The center is committed to the promoting and deepening Bucknell's tradition of humanistic inquiry through grants and fellowships to support faculty and student research, innovative pedagogy, and a sense of community among humanities faculty and students through the Humanities Council and Humanities Student Council, as well as space to gather, study, and research including offices for student thesis writers, a digital humanities lab, and a faculty-donated library. It also coordinates programming ranging from the student-organized Humanities Week to guest speakers and faculty colloquia as part of its annual themed programming. Recent themes include "Non/Humanity" (2021–22), "Pandemics" (2022–23), and "Colonial entanglements" (2023–24).[31]

The Geisinger-Bucknell Autism and Developmental Medicine Institute was formed in April 2013 as a partnership between Bucknell and the Geisinger Health System, headquartered in nearby Danville. This facility combines clinical treatment and interdisciplinary research on neurodevelopmental disorders.[32]

Other centers and institutes include: the Bucknell Institute for Lifelong Learning, the Bucknell Institute for Public Policy, the Center for Social Science Research, the Center for the Study of Race Ethnicity and Gender, the China Institute, the Griot Institute for the Study of Black Lives and Cultures, the Stadler Center for Poetry and Literary Arts, and the Weis Center for the Performing Arts.[33]

Study Away

[edit]Almost half of all Bucknell students study abroad through a large number of exchanges with partner institutions, as well as Bucknell operated sites in Accra, Athens, Granada, London, Singapore, Sydney, and Tours. Bucknell also runs a semester-long program in Washington, D.C., to support students with an interest in government public service. [34]

Rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| Liberal arts | |

| U.S. News & World Report[35] | 31 |

| Washington Monthly[36] | 60 |

| National | |

| Forbes[37] | 93 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[38] | 81 |

In the 2025 edition of U.S. News & World Report, Bucknell tied for 31st in the "National Liberal Arts Colleges" category.[39] The 2024 edition of Forbes rated Bucknell 93rd in its list of "America's Top Colleges" and 22nd among liberal arts colleges.[40] The 2022 edition of the Times Higher Education U.S. College Rankings placed Bucknell 27th among U.S. liberal arts colleges.[41] In 2024, Washington Monthly, which ranks colleges and universities based on perceived contribution to the public good as measured by social mobility, research, and promoting public service, ranked Bucknell 60th among liberal arts colleges.[42] In 2024, the Payscale "College Salary Report" ranked Bucknell 40th among all colleges and universities and 10th among liberal arts colleges for salary potential.[43][44] Bucknell is considered one of the "Hidden Ivies", an institution reputed to provide an education comparable to that of Ivy League institutions.

Admissions

[edit]U.S. News & World Report classifies Bucknell's selectivity as "more selective".[29] For the Class of 2028 (enrolled Fall 2024), Bucknell received 11,377 applications and accepted 3,291 (28.9%), with 994 enrolling (30.2% yield rate). The middle 50% range of SAT scores for the enrolled freshmen was 640–740 for reading and writing, and 670–760 for math, while the ACT middle 50% composite range was 31–34. Beginning in 2022, Bucknell like most of its peer institutions is now test optional, meaning applicants can choose whether or not to submit SAT and ACT scores when applying. The average high school grade point average (GPA) for enrolled freshmen the class of 2028 was 3.62.[45]

Athletics

[edit]

Bucknell is a member of the Patriot League for Division I sports (Division I FCS in football).

In 2005, the men's basketball team went to the NCAA men's basketball tournament and became the first Patriot League team to win an NCAA tournament game, upsetting Kansas 64–63. The victory followed a year that included wins over #7 Pittsburgh and Saint Joseph's. They lost to Wisconsin in the following round but received the honor of "Best Upset" at the 2005 ESPY Awards.[46]

Traditions and symbols

[edit]On April 17, 1849, the trustees approved the current Bucknell seal. The seal shows the sun, an open book and waves. The sun symbolizes the light of knowledge, while the book represents education surmounting the storms and "waves" of life.[47] Bucknell's colors are blue and orange, having been approved by a committee of students in 1887.[48] The bison is the current mascot of Bucknell University. In 1923, Dr. William Bartol suggested the animal due to Bucknell's location in the Buffalo Valley.[49] The school cheer is "'ray Bucknell!"

Student life

[edit]Bucknell has over 150 student organizations,[50] a historical downtown cinema (Campus Theatre), a makerspace and crafts studio (7th Street Studio) and a calendar full of visiting speakers, art exhibits, performances, recitals, and year-end celebrations such as the "Chrysalis" ball and dinners sponsored by international student organizations.

Bucknell's student newspaper, The Bucknellian, is printed weekly. Its headquarters are in Stuck House on South 7th Street on the campus.[51] The college radio station is WVBU-FM.

Spratt House is the home of the institution's Army Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) program.

Fraternities and sororities

[edit]As of 2024[update], Bucknell University has seven active fraternity chapters and nine active sorority chapters:[52]

The Alpha Phi chapter of the Kappa Sigma fraternity was put on probation for disciplinary reasons and then closed in 2017.[53] Five fraternities are no longer recognized by the school: Delta Upsilon, Kappa Delta Rho, Kappa Sigma, Pi Beta Phi Women's, and Tau Kappa Epsilon.[54]

Alumni

[edit]Alumni of Bucknell University include: Burma's first physician Shaw Loo (class of 1863),[55] National Baseball Hall of Fame pitcher Christy Mathewson (1902), Pro Football Hall of Fame Fullback/Linebacker Clarke Hinkle (1932), actor Ralph Waite (1952), novelist Philip Roth (1954), investor and philanthropist Ken Langone (1957), actor Edward Herrmann (1965), literary theorist and translator Peggy Kamuf (1969), CBS media executive Leslie Moonves (1971), author and pastor of Redeemer Presbyterian in New York City Tim Keller (1972),[56] 2016 Pulitzer Prize winner for poetry, Peter Balakian (1973), New Jersey congressman Rob Andrews (1979), CEO of Lord & Taylor and The Children's Place, Jane T. Elfers (1983), entrepreneur Jessica Jackley (2000), and basketball player Mike Muscala (2013).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "The Facts About Bucknell". Bucknell University. n.d. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "U.S. and Canadian 2022 NTSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2022 Endowment Market Value, Change in Market Value from FY21 to FY22, and FY22 Endowment Market Values Per Full-time Equivalent Student (Excel)". NACUBO. February 17, 2023. Retrieved 2023-08-23.

- ^ a b c d e "Bucknell Facts 2022–23" (PDF). Bucknell University. Bucknell University Division of Communications. December 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- ^ "Direction, Defined. Our Brand Guidelines" (PDF). Bucknell University. Bucknell University Division of Communications. August 2017. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "History and Traditions". Bucknell University. n.d. Archived from the original on 4 January 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ "The University's Founding". Bucknell University Bucknell University.

- ^ "History & Traditions of Bucknell University". www.bucknell.edu. Retrieved 2024-01-31.

- ^ James Orin Oliphant, The Rise of Bucknell University. Chapters 2 and 3.

- ^ "The Female Institute". Bucknell University Bucknell University.

- ^ Brackney, William H. (2008). Congregation and Campus: North American Baptists in Higher Education (1 ed.). Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-88146-130-5. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- ^ "Milestones – Benefactor William Bucknell". Bucknell University.

- ^ Bonan, Tom. "From the Special Collections/University Archives: Jens Larsen, Bucknell University's Architect". Bucknell University. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ Stodart, Haley. "From the Special Collections/University Archives: Who is Ellen Clark Bertrand?". Bucknell University. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ [1] Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine "Continued Expansion Bucknell University."

- ^ "The Bucknell Campus" Archived 2017-01-13 at the Wayback Machine University website. Retrieved January 1, 2016

- ^ "Open House". www.bucknell.edu. 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ Christy Mathewson Archived 2015-05-15 at the Wayback Machine Historic Baseball. Retrieved January 1, 2016

- ^ "Christy Mathewson Stats" Archived 2016-12-06 at the Wayback Machine Baseball Almanac. Retrieved January 1, 2016

- ^ "The Bucknell Farm". bucknell.edu. Bucknell University. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "Bucknell Set to Celebrate Solar Project Completion". bucknell.edu. Bucknell University. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "Sustainability at Bucknell". bucknell.edu. Bucknell University. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ "Century Plant brings excitement to Bucknell's greenhouse". wnep.com. 2023-01-05. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ "SELF-GUIDING TOUR OF THE BIOLOGY GREENHOUSE". www.departments.bucknell.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-03.

- ^ Dandes, Rick (2023-04-20). "Bucknell Greenway walking path to be commissioned today". The Daily Item. Retrieved 2024-05-07.

- ^ "Majors & Minors". Bucknell University.

- ^ "Bucknell University". nces.ed.gov. U.S. Dept of Education. Retrieved January 26, 2023.

- ^ "Graduate Outcomes". bucknell.edu. Buckenll University. Retrieved February 10, 2023.

- ^ a b "About the College of Arts & Sciences". Bucknell University.

- ^ a b c "Bucknell University Rankings".

- ^ "Freeman College of Management Ranks 17 in Poets&Quants (2022)". Poets&Quants. 27 January 2022.

- ^ "Bucknell Humanities Center". Bucknell University.

- ^ "Geisinger-Bucknell ADMI". Geisinger.

- ^ "Bucknell Academic Centers and Institutes". Bucknell University.

- ^ "Global and Off-Campus Education". Bucknell University Bucknell University.

- ^ "2024-2025 National Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Liberal Arts Colleges Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "Bucknell University Rankings". U.S. News and World Report. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ "Forbes America's Top Colleges List 2024". Forbes. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ "Bucknell University". Times Higher Education (THE). Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ "2022 Liberal Arts Colleges Ranking". Washington Monthly. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ "College Salary Report: Best Universities and Colleges by Salary Potential". Payscale.com. September 2024. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ "College Salary Report: Best Liberal Arts Colleges by Salary Potential". Payscale.com. September 2024.

- ^ "Fast Facts". Bucknell University.

- ^ "2015 ESPYS – Past Award Winners". espn.com/espys. Retrieved December 15, 2015.

- ^ "University Seal". Bucknell University. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012.

- ^ "University Colors". Bucknell University. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012.

- ^ "University Mascot". Bucknell University. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012.

- ^ "Get Involved @ Bucknell". getinvolved.bucknell.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ^ Spears, Natalie (2016-09-22). "The Bucknellian's 120th Anniversary". The Bucknellian. Retrieved 2024-05-04.

- ^ "Fraternity & Sorority Chapters". www.bucknell.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ Worthington, Elizabeth (2017-09-01). "Kappa Sigma fraternity dissolved". The Bucknellian. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ "Unrecognized Organizations". www.bucknell.edu. Retrieved 2024-05-06.

- ^ po, myo min (2020-10-01). "The Day When a US President Praised a Student From Myanmar". The Irrawaddy. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- ^ "Jane T. Elfers: Executive Profile & Biography - Bloomberg". www.bloomberg.com.

Further reading

[edit]- Theiss, Lewis Edwin, Centennial history of Bucknell University: 1846–1946, Grit Publishing Co. Press (1946)

- The rise of Bucknell University Oliphant, James Orin, The Rise of Bucknell University] Appleton-Century-Crofts (1965)

- Krist, Robert, Bucknell University, Harmony House (1990), ISBN 9780916509293