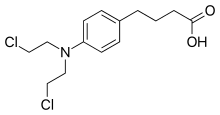

Chlorambucil

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Leukeran, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682899 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ? |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | 1.5 hours |

| Excretion | N/A |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.603 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C14H19Cl2NO2 |

| Molar mass | 304.21 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Chlorambucil, sold under the brand name Leukeran among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), Hodgkin lymphoma, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[2] For CLL it is a preferred treatment.[3] It is given by mouth.[3]

Common side effects include bone marrow suppression.[3] Other serious side effects include an increased long term risk of further cancer, infertility, and allergic reactions.[3] Use during pregnancy often results in harm to the baby.[3] Chlorambucil is in the alkylating agent family of medications.[3] It works by blocking the formation of DNA and RNA.[3]

Chlorambucil was approved for medical use in the United States in 1957.[3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4][5] It was originally made from nitrogen mustard.[3]

Medical uses

[edit]Chlorambucil's current use is mainly in chronic lymphocytic leukemia, as it is well tolerated by most patients, though chlorambucil has been largely replaced by fludarabine as first-line treatment in younger patients.[6] It can be used for treating some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Waldenström macroglobulinemia, polycythemia vera, trophoblastic neoplasms, and ovarian carcinoma. Moreover, it also has been used as an immunosuppressive drug for various autoimmune and inflammatory conditions, such as nephrotic syndrome.

Side effects

[edit]Bone marrow suppression (anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia) is the most commonly occurring side effect of chlorambucil. Withdrawn from the drug, this side effect is typically reversible. Like many alkylating agents, chlorambucil has been associated with the development of other forms of cancer.

Less commonly occurring side effects include:

- Gastrointestinal Distress (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and oral ulcerations).

- Central Nervous System: Seizures, tremors, muscular twitching, confusion, agitation, ataxia, and hallucinations.

- Skin reactions

- Hepatotoxicity

- Infertility

- Hair Loss

Pharmacology

[edit]Mechanism of action

[edit]Chlorambucil produces its anti-cancer effects by interfering with DNA replication and damaging the DNA in a cell. The DNA damage induces cell cycle arrest and cellular apoptosis via the accumulation of cytosolic p53 and subsequent activation of Bcl-2-associated X protein, an apoptosis promoter.[7][8][9]

Chlorambucil alkylates and cross-links DNA during all phases of the cell cycle, inducing DNA damage via three different methods of covalent adduct generation with double-helical DNA:[10][11][12]

- Attachment of alkyl groups to DNA bases, resulting in the DNA being fragmented by repair enzymes in their attempts to replace the alkylated bases, preventing DNA synthesis and RNA transcription from the affected DNA.

- DNA damage via the formation of cross-links which prevents DNA from being separated for synthesis or transcription.

- Induction of mispairing of the nucleotides leading to mutations.

The precise mechanisms by which chlorambucil acts to kill tumor cells are not yet completely understood.

Limitations to bioavailability

[edit]A recent study has shown Chlorambucil to be detoxified by human glutathione transferase Pi (GST P1-1), an enzyme that is often found over-expressed in cancer tissues.[13]

This is important since Chlorambucil, as an electrophile, is made less reactive by conjugation with glutathione, thereby making the drug less toxic to the cell.

Shown above, Chlorambucil reacts with glutathione as catalyzed by hGSTA 1-1 leading to the formation of the monoglutathionyl derivative of Chlorambucil.

Chemistry

[edit]Chlorambucil is a white to pale beige crystalline or granular powder with a slight odor. When heated to decomposition it emits very toxic fumes of hydrogen chloride and nitrogen oxides[12]

History

[edit]Nitrogen mustards arose from the derivatization of sulphur mustard gas after military personnel exposed to it during World War I were observed to have decreased white blood cell counts.[14] Since the sulphur mustard gas was too toxic to be used in humans, Gilman hypothesized that by reducing the electrophilicity of the agent, which made it highly chemically reactive towards electron-rich groups, then less toxic drugs could be obtained. To this end, he made analogues that were less electrophilic by exchanging the sulphur with a nitrogen, leading to the nitrogen mustards.[15]

With an acceptable therapeutic index in humans, nitrogen mustards were first introduced in the clinic in 1946.[16] Aliphatic mustards were developed first, such as mechlorethamine hydrochloride (mustine hydrochloride), which is still used in the clinic today.

In the 1950s, aromatic mustards like chlorambucil were introduced as less toxic alkylating agents than the aliphatic nitrogen mustards, proving to be less electrophilic and react with DNA more slowly. Additionally, these agent can be administered orally, a significant advantage.

Chlorambucil was first synthesized by Everett et al.[7]

References

[edit]- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 Oct 2023.

- ^ "Chlorambucil". National Cancer Institute. 17 September 2014. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Chlorambucil". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ Rai KR, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, Kolitz J, Elias L, Shepherd L, et al. (December 2000). "Fludarabine compared with chlorambucil as primary therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 343 (24): 1750–1757. doi:10.1056/NEJM200012143432402. PMID 11114313.

- ^ a b "Leukeran (Chlorambucil) Drug Information: Description, User Reviews, Drug Side Effects, Interactions – Prescribing Information at RxList". RxList. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ "chlorambucil – CancerConnect News". CancerConnect News. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ "Leukeran (chlorambucil) Tablets" (PDF). GlaxoSmithKline. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-22 – via emOnc.org - A Free Hematology/Oncology Reference.

- ^ "Chlorambucil". Drug Bank. Archived from the original on 2017-01-03.

- ^ Di Antonio M, McLuckie KI, Balasubramanian S (April 2014). "Reprogramming the mechanism of action of chlorambucil by coupling to a G-quadruplex ligand". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 136 (16): 5860–5863. doi:10.1021/ja5014344. PMC 4132976. PMID 24697838.

- ^ a b "Chlorambucil | C14H19Cl2NO2". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 2015-12-22. Retrieved 2015-12-21.

- ^ Parker LJ, Ciccone S, Italiano LC, Primavera A, Oakley AJ, Morton CJ, et al. (June 2008). "The anti-cancer drug chlorambucil as a substrate for the human polymorphic enzyme glutathione transferase P1-1: kinetic properties and crystallographic characterisation of allelic variants". Journal of Molecular Biology. 380 (1): 131–144. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.066. hdl:2108/101037. PMID 18511072.

- ^ Neidle S, Thurston DE (2006). "Chemical Approaches to the Discovery and Development of Cancer: Serendipity and Chemistry". Medcape. Archived from the original on 2014-06-23. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- ^ Gilman AG, Rall TW, Nies AS, Taylor P (1990). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York: Pergamon.

- ^ Anslow WP, Karnofsky DA (May 1948). "The intravenous, subcutaneous and cutaneous toxicity of bis (beta-chloroethyl) sulfide (mustard gas) and of various derivatives". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 93 (1): 1–9. PMID 18865181.

External links

[edit]- Leukeran (manufacturer's website)

- "Chlorambucil". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.